Research

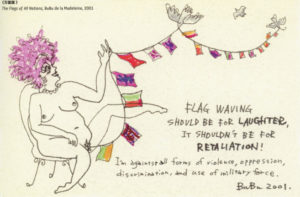

BuBu de la Madeleine came to renown through Dumb Type’s performance piece S/N which toured twenty cities in fifteen countries between 1994 and 1996. Especially notable was the last scene played to the sweet melody of “Amapola” by Nana Mouskouri. In it, BuBu reclined on a chair completely nude, slowly moving from right to left on the stage, while pulling the flags of all nations from her barely lit crotch. In the previous scene, entitled “Love Song”, BuBu chatted with Peter Golightly and Teiji Furuhashi about her past sex life as a married heterosexual woman, her then current occupation as a sex worker and an educator. Her face was elaborately made-up and she was wearing a skimpy black chemise. BuBu’s talking head was projected onto the right half of the big screen. The left half of the screen showed the close-up of Teiji Furuhashi as he put on makeup to transform himself into a drag queen and discussed his life as a HIV positive gay man, while sitting on the top space of the construction that also functioned as a screen.

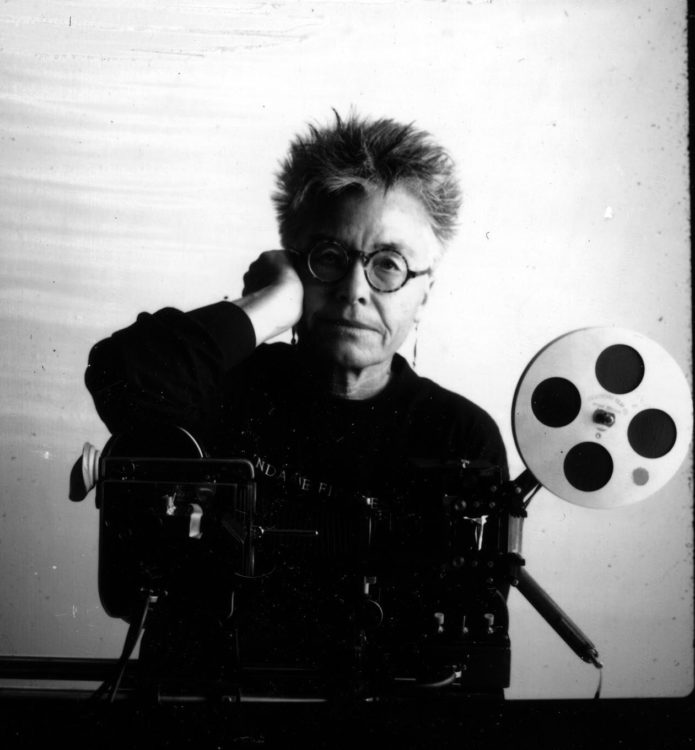

Peter Golightly originally addressed her as “BuBu”, which is how the audience came to know her. But in the official credits, she used her real, legal name. When the tour of S/N ended, BuBu left Dumb Type and started to work as a solo artist, a social activist confronting the issues of HIV/AIDS and a drag queen/king. She is now officially known as BuBu de la Madeleine. Through performing in S/N, “BuBu” became a public persona.

BuBu was born in Osaka in 1961 and grew up in the greater Kansai region. She graduated from Kyoto City University of Arts in 1985 where she created theatrical works with fellow students. After a five-year hiatus, in late 1991 she rejoined her friends who had formed an artist collective named Dumb Type. In 1992 Teiji Furuhashi sent a letter to a couple of dozen friends.1 In it he came out as HIV positive and living with AIDS. This led to the creation of the S/N installation/performance project that tackled the dissonance surrounding contemporary social issues – sex inequality, racial and ethnic minority discrimination, politics of gender, HIV/AIDS and sexuality. S/N triggered various movements beyond performance, toward activist engagement and community outreach.

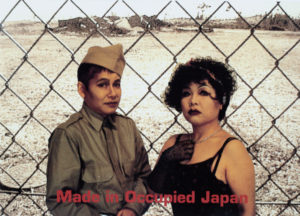

BuBu de la Madeleine and Yoshiko Shimada, Made in Occupied Japan, 1998, photo collage © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine & Yoshiko Shimada

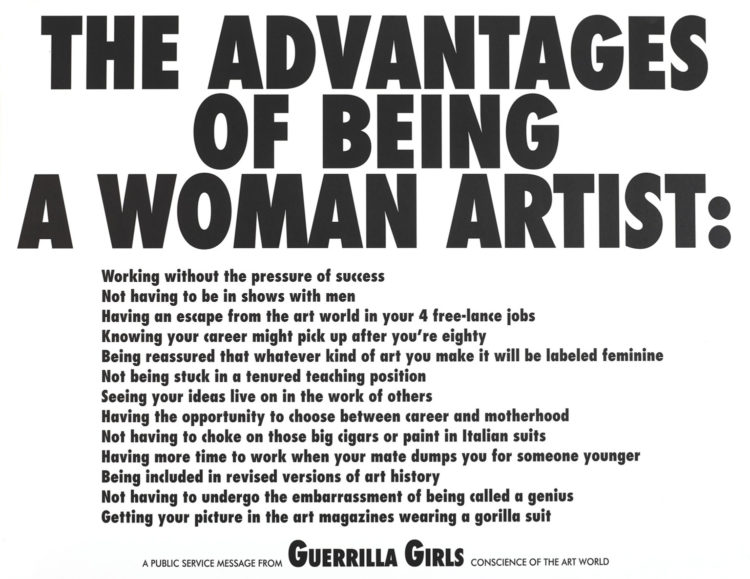

In 1998 BuBu collaborated with Yoshiko Shimada, who is known for her controversial works addressing feminist issues such as comfort women and colonialism. Entitled Made in Occupied Japan after the certificates of origin attached to the merchandise made during the US occupation era (1945–1952), the work consists of a couple of dozen photo collages and a video. In them, the two artists play the roles of both women and men: a US military man (Shimada) and a Japanese whore (BuBu) standing in front of the wired fence surrounding the US base; BuBu in a baby doll posing on the clam shell in the fashion of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus while an anti-sex work feminist (Shimada) tries to cover her up; Shimada showing off a dangling ferret from the unfastened trousers of the camouflage uniform, among others. These pieces reveal with humour how the so-called femininity and masculinity that we tend to take for granted are laughably groundless.

After La Dolce Vita (2001), a video work in which BuBu lies on the dark beach with her nude body as a bridge between water and land, she arrived at the subject matter of “a mermaid’s territory”. In 2004 she created Territory of Mermaid/August Water. In the aftermath of her best friend’s death, she began to examine how a mermaid symbolised a being. For BuBu at this time, the mermaid resisted the rough waves in the space between the sea – the world of the dead – and the land. During the 2010s, BuBu became more aware of the boundary between her own body and those of the others through her everyday life as a sex worker. This was amplified by her experience as a domestic care giver for a family member. The initial transgression of an individual’s physical body, the trespass of a personal boundary, can be defined as the moment of touching or being touched. There are two ways for that to happen: as an expression of friendliness and care, or as the desire to conquer and attack. These trespasses are repeated on a larger scale at the borders of national territories, against ethnic groups, genders and sexualities, and we continue to be bombarded by these assaults on our daily lives. BuBu has come to think that water, which is the den and territory of a mermaid, can function as a metaphor for the world in which women and the other subjugated minorities can live.

For numerous years, BuBu suffered from chronic psoriasis, a skin disease. Seeing her dry skin peel, she came up with the idea that perhaps a mermaid would moult. This evolved into her 2019 installation piece, A Mermaid’s Territory and Shedding of Old Skin. The structure, made with wires, was covered with pieces of old fabric taken from garments BuBu had worn, her favourite linens and the costumes of drag queens who performed at the clubs. The huge structure signified the mermaid’s skin after moulting. From the skin, the scales – pieces of cloth – had peeled and pattered. As the pieces of fabric directly touched the skin – the inner and outer boundary of the body which is the individual’s territory – they had absorbed various memories. Those scales had departed from the mermaid’s body, transformed into a line of flags and flown up into the sky.

BuBu de la Madeleine, A Mermaid’s Territory – Flags and Internal Organs, 2022, installation view, Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo, photo: Kanichi Kanegae, courtesy Ota Fine Arts © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine

BuBu de la Madeleine, A Mermaid’s Territory – Flags and Internal Organs, 2022, installation view, Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo, photo: Kanichi Kanegae, courtesy Ota Fine Arts © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine & Ota Fine Arts

BuBu de la Madeleine, A Mermaid’s Territory – Flags and Internal Organs, 2022, installation view under construction, Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo, courtesy Ota Fine Arts © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine & Ota Fine Arts

In 2020, BuBu had her ovaries and uterus removed because she had cysts and fibroids. While the surgery brought her physical pain, BuBu was astonished to find out that pre- and post-operation, her feelings and senses did not change at all. The ovaries and the uterus were simply colleagues to other internal organs that worked together within her. Nevertheless, they were burdened with bigger and more complicated meanings. Having them extracted from her body gave BuBu a refreshing sensation. Unlike her past work, which dealt with the surface of the body, her work in the 2022 installation Mermaid’s Territory: Flags and Internal Organs, had the innards also moult. BuBu came to believe the body can be reborn from the inside. The sense of regeneration guides the viewers to rethink the nuances surrounding life and death, gender roles and procreation. At this point BuBu’s mermaid is a gender queer amalgam of a marine fauna and a pollinating flora.

BuBu de la Madeleine, BuBu plays Saburo Kitajima, 2019, drag king performance at the event DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER, Club Metro, Kyoto © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine

When BuBu started her artistic career, she identified as a heterosexual, cis-gendered woman. As her work has evolved over the years, however, she has understood herself better. She relates more to the gender queer mermaid, and can now reach out to broader audiences and more diverse communities, from which she previously felt separated. She is untethered from the definitions she was born into, and like the mermaid, she becomes free. The array of flags leaving the mermaid’s body, and flying up to ethereal plains, celebrates this experience and those who have been unfettered from earthly restraints.

BuBu de la Madeleine, One Genderqueer Being Pollinates the Other #001, 2022, drawing, 27.4 × 19.5 cm © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine

BuBu de la Madeleine, One Genderqueer Being Pollinates the Other #003, 2022, drawing, 19.5 x 27.4 cm © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine

BuBu de la Madeleine, One Genderqueer Being Pollinates the Other #002, 2022, drawing, 19.5 x 27.4 cm © Courtesy BuBu de la Madeleine

A Mermaid’s Territory – Flags and Internal Organs

By BuBu de la Madeleine

The mermaid moults.

Their skin ruptures.

Their interior becomes their exterior,

their organs, a new epidermis.

To whom would the mermaid give permission to touch them?

When split apart, a treatment is required.

Is it possible to be cured by another?

The mermaid moults.

We think the mermaid’s internal organs are taciturn.

But in fact their innards sing in such bellowing voices, as if echoing from the depths of the sea.

When the mermaid transforms themselves,

intently they listen to the songs that seep through the cracks in their own skin.

The mermaid moults.

A mermaid is a creature that looks back at themselves from the reverse, from the depths of the water, and from somewhere deep within their mirror.

The mermaid moults.

I cannot see my own internal organs.

When my surface is cut open, however, my viscera become

my skin anew.

Little by little, the new exterior transforms into flags of various colours,

and as they peel themselves from me, they will form

random lines

and head

for a place far

beyond the sky.

The mermaid’s flags are

Lamentations for the dead.

The symbols of disobedience.

And,

They celebrate the emancipation

from earthly

restraints2

See the English translation of Teiji Furuhashi’s letter, “Life with Virus: Celebrating My Announcement of HIV Infection”, Visual AIDS, 19 July 2021, https://visualaids.org/blog/furuhashi-letter

2

This poem was first published along with an English translation by Akiko Mizoguchi and Emalyn in a flyer distributed at BuBu de la Madeleine’s solo exhibition A Mermaid’s Territory – Flags and Internal Organs, Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo, 9 April–4 June 2022. This version, revised in May 2023, appears here for the first time.

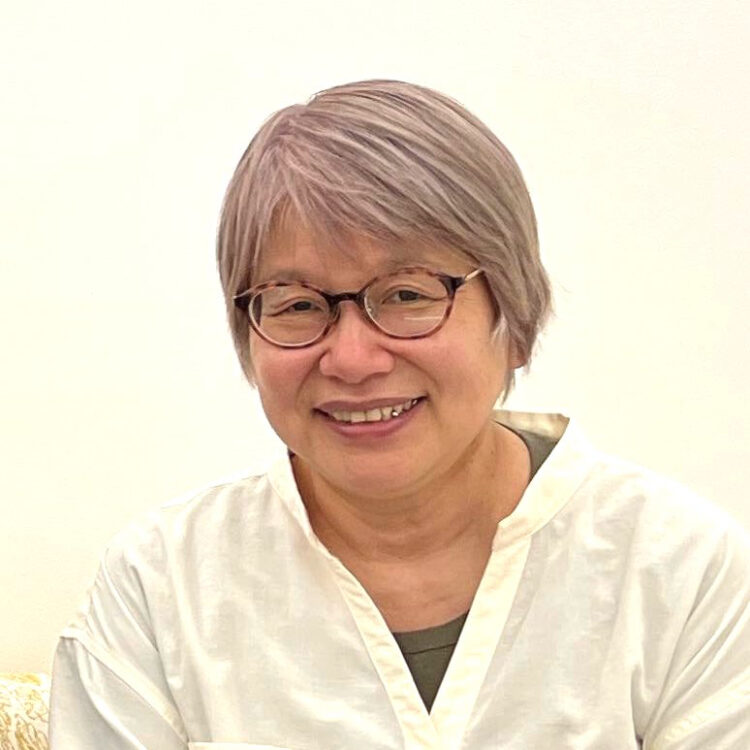

Akiko Mizoguchi is a queer visual culture theorist. She has published extensively on the arts and popular culture. Her award-winning 2015 book: BL shinkaron: Bōizurabuga shakaiwo ugokasu [Theorising BL as a Transformative Genre: Boys’ Love Moves the World Forward] has been translated into Chinese and Korean. She teaches at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan, as Associate Professor.

Emalyn is an artist and a story teller. She earned a master’s degree in American Studies from Columbia University. Her research closely examines how Japanese media, particularly manga, dominated the American market in the late 1990s and early 2000s, fundamentally changing American popular culture. She has a particular interest in why Japanese media had such a strong appeal to teenage girls, queer youth and other underrepresented communities in the United States.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Akiko Mizoguchi & Emalyn, "BuBu de la Madeleine’s Mermaid Revolution." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/bubu-de-la-madeleine-et-la-revolution-des-sirenes/. Accessed 20 January 2026