Research

Elisabeth Geertruida Wassenbergh, The Doctor’s Visit, 1750-1760, oil on canvas, 40 x 49,5 cm,, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Throughout history, women have played indispensable roles as artists, art patrons and heads of workshops, amongst others. Over the last fifty years, extensive research has unveiled numerous names and artistic pathways, contradicting modernist beliefs that the artist archetype predominantly referred to men.1 In the eighteenth-century Dutch Republic, many women artists emerged: drawing, sculpting, practising paper cutting and painting in every genre, including history paintings, portraits, genre paintings, landscapes and still lifes, sometimes in miniature form. They acquired their training through family members, apprenticeships or by studying model books and prints.2 Whether they carried out their artistic labour in private spheres, like Elisabetta Geertruida Wassenbergh (1727–1778), or gained an income by selling their works, like Johanna Koerten (1650–1715) and Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), all these women contributed to the eighteenth-century Dutch art scene. This article aims to offer a glimpse into the creative contributions of several noteworthy Dutch women artists across diverse disciplines.

Sara Troost, Portrait of Johanna Capelle (1698-1774), 1762, pastel on parchment, 69.3 x 57.2 cm., Amsterdam Museum.

Portraits and miniatures

The Dutch Republic in the eighteenth century differed from the surrounding absolutist states through a lack of a dominant court culture. Political control in the Dutch Republic was held by a small group of regents. Urban life flourished as the cities continued to serve as centres of domestic commerce and international trade. The Republic’s wealth, which had peaked in the preceding century, was distributed amongst a broad, affluent middle class, who, like the upper class, were important buyers of artworks.

In the early eighteenth century, demand grew for a particular style of portraiture, depicting entire families or individual family members interacting in a domestic setting. These conversation pieces often included personal attributes which referred to an individual’s qualities or profession. In portraits too, patrons frequently had themselves portrayed with personalised attributes. Artists responded to this demand using diverse media, including pastels and oil painting. For example, copyist and pastelist Sara Troost (1732–1803) received multiple commissions for portraits from wealthy Amsterdam families. The realistic facial expressions and detailed execution of her portraits became characteristic of her personal style, as seen in her Portrait of Johanna Capella (1762), where she portrays the sitter, the head of a camphor distillery, as an erudite woman who gives the impression of being disturbed while reading.3

Miniatures saw increased appreciation as a distinct art form during the eighteenth century. Amongst women artists, this art form was favoured due in part to its practical advantages, such as the portable size of the easel which facilitated its use in domestic settings. Miniatures were often commissioned as gifts to loved ones and therefore mainly circulated in intimate surroundings.4 Due to their small size, they could be worn or carried closely by the intended recipient. The latter part of the eighteenth century also saw rising demand amongst the middle class for smaller, more affordable portraits. Consequently, an itinerant group of artists travelled between Dutch cities, specialising in creating silhouettes, using advertisements to announce their stay and to attract a clientele. These silhouettes presented an affordable and easily reproducible artistic method, capturing the subject’s projected shadow by manually tracing it onto paper. A few women practiced this art form, such as the Amsterdam-based artist Johanna Sophia Mannigel-Forberger (1760–1846).

Miniatures were created in various media, including wood, cardboard or paper. Amsterdam artist J. Koerten was one of the very few well-known miniaturists at the time to excel in paper cutting. She worked by making small, delicate carvings into the paper, creating realistic portraits, as well as religious and historical scenes, landscapes, still lifes and allegories. She had a large clientele, including members of the highest European circles, and opened her house to artists, art collectors and other interested parties, where she invited them to view her work. This testifies not only to her agency as an artist, but also to her role as a mediator in the sale of her own work.

Ivory became a widely used medium for miniatures in the eighteenth century. One artist to achieve recognition using this medium was Henrietta Wolters-van Pee (1692–1741). She learned the principles of miniature painting from the sculptor, painter and miniaturist Jacob Christopher LeBlon (1670–1741), to whom she was originally apprenticed to learn drawing and painting. She received commissions from the highest members of Dutch society and is even said to have turned down several requests from foreign monarchs to serve as court painter. Self-portrait (1732) shows the Amsterdam-based artist at the age of forty. This work illustrates her artistic talent, demonstrated by the realistic and detailed rendering of the various textures, such as the lace collar and the pearl necklace.

Medium-sized portraits such as those by E. G. Wassenbergh also became popular in this period. Born into an artistic family, she painted both portraits and genre pieces in a small format. Her works showcase the naturalistic and refined painting style greatly admired by contemporaries. Little is known about her, but she worked from home and used her family members as models for her work. While the majority of her surviving works are now part of the Groninger Museum’s collection, the Rijksmuseum’s collection holds a genre painting titled Doctor’s Visit (1750–1760).

Henrietta Wolters-van Pee, Selfportrait, 1732, miniature painting on ivory, 6.8 x 5.5 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Genre scenes

Genre paintings are carefully composed scenes depicting individuals from different social classes engaged in their everyday life. These already popular motifs and themes were reproduced with a refined painting technique that perpetuated the appeal of genre scenes as highly sought-after collector’s pieces. Artists also incorporated allegorical references or hidden messages readable by the contemporary viewer.5

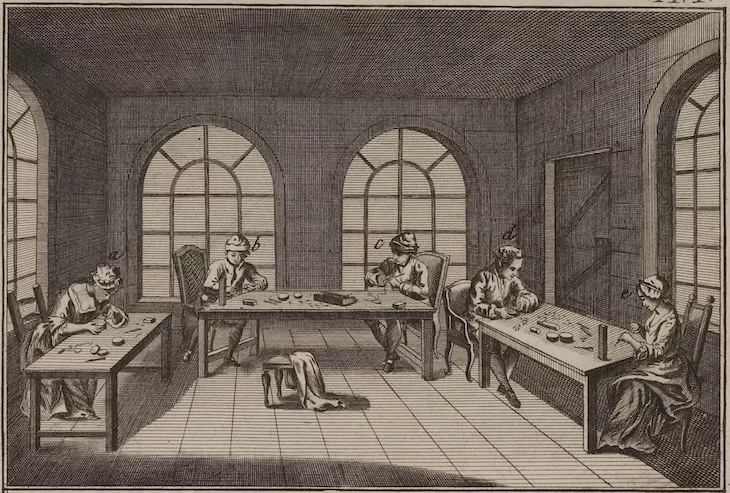

G. Wassenbergh’s Doctor’s Visit depicts a theme already popular in the seventeenth century. In a domestic setting, a group of figures is positioned around a seated woman. Next to her stands a surgeon, who feels her pulse while looking into a glass of liquid. This scene shows the contemporary medical act in which surgeons, also known as “piss viewers”, were thought to be able to diagnose a client by examining their urine.6 E. G. Wassenbergh incorporates underlying symbolic references into this theme. For example, the boy in the lower left corner shooting arrows into an upturned hat could be identified as Cupid.[7] The woman in the painting can thus be interpreted as suffering from love sickness or pregnancy.

Rachel Ruysch, Still Life with Flowers on a Tabletop, 1716, oil on canvas, 48.5 x 39.5 cm., Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Floral still life paintings

During the eighteenth century, the genre of floral still life painting was in great demand even beyond the borders of the Dutch art market. Women artists in particular responded to the continuing demand for such paintings. Botanical drawings were also very popular, due to the increasing scientific knowledge in fields such as horticulture.8 As a result, the realms of science and art intertwined. For example, as preliminary studies for her drawings, Dutch draftsperson Dorothea Kreps (1734–1772) studied flower and plant species in the botanical gardens in Amsterdam as did floral painter R. Ruysch.

R. Ruysch is one of the most celebrated floral painters of all time. The Amsterdam artist was apprenticed to floral painter Willem van Aelst (1627–1683).9 Her artistic talent is shown in the great precision of every element in her dynamic bouquets, as seen in Still Life with Flowers on a Marble Table Top (1716). She used colour and light to enhance perspective, skilfully created compositions featuring a wide range of indigenous and exotic flower species, each depicted in various stages of growth and based on first-hand botanical observations.

Also in 1716, floral painter Margaretha Haverman (1693–?) made A Vase of Flowers (1716), which has been in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection since 1871. Born in Breda, M. Haverman moved to Amsterdam in 1703. She became a pupil of the well-known floral painter Jan van Huysum (1682–1749) in 1715. Only one other floral still life known by her hand exists, in the collection of the Statens Museum for Kunst in Denmark. Both paintings show a lush bouquet against a dark background, rendered in a very natural way.

The works of R. Ruysch and M. Haverman stood out for their exceptional quality within the genre of floral still life painting. Both artists held a unique position and drew the attention of other artists and art patrons on an international level. Along with seventeenth-century floral painter Maria van Oosterwijck (1630–1693), R. Ruysch was one of two women court painters to the Elector Palatine Johann Wilhelm von der Pfalz and noblewoman Anna Maria Luisa de Medici, both leading art patrons. M. Haverman’s artistic talent also resulted in her enrolment at the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris in 1722, which had previously accepted only three female members.10

Margareta Haverman, A Vase of Flowers, 1716, oil on wood, 79.4 x 60.3 cm., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Clearing a pathway

This article gives a glimpse of the past through Dutch women artists, revealing their artistic contributions and highlighting their integral role in art history. Each artist, whether wielding a brush, pencil or pair of scissors, uniquely expressed her artistic endeavours. Ongoing research as well as exhibitions, such as Making her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe 1400–1800 (Baltimore/Toronto, 2023–2024) and Ingenious Women: Women Artists and Their Companions (Basel/Hamburg, 2023–2024) or Women Masters (Madrid, 2023–2024) are paving the way for recognition of numerous female artists and serve as great inspiration for future initiatives.

Miller, Diane, “Gender and the Artist Archetype: Understanding Gender Inequality in Artistic Careers’” Sociology Compass 10 (2016) 2, pp. 119–131.

2

Exh. Cat. Making her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe 1400–1800, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Goose Lane Editions, New Brunswick, 2023.

3

Kroon, Anja, “Een kamferstokerij op het Crayenest [A Camphor Distillery on the Crayenest]” in: HeerlijkHeden 172 (2017), pp. 12–17.

4

Pappe, Bernd & Schmieglitz-Otten, Juliane, Portrait miniatures: artists, functions and collections, Petersberg (Michael Imhof Verlag), 2018.

5

See : Bell, Esther (red.), The Age of Elegance: the Joan Taub Ades Collection, New York (Morgan Library & Museum) 2011 and Aono, Junko, Confronting the Golden Age: imitation and innovation in Dutch genre painting (1680–1750), Amsterdam (Amsterdam University Press) 2015 .

6

Franits, Wayne, Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting: Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution, New Haven (Yale University Press) 2004.

7

See Roekel, J. van, De schildersfamilie Wassenbergh en een palet van tijdgenoten [The Wassenbergh Family of Painters and a Palette of Contemporaries], Bedum (Profiel), 2006 and Hall, James, Hall’s iconografisch handboek. Onderwerpen, symbolen en motieven in de beeldende kunst [Hall’s Iconographic Handbook. Subjects, Symbols, and Motifs in the Visual Arts], Leiden (Primavera Pers) 1992.

8

Segal, Sam and Alen, Klara, Dutch and Flemish flower pieces: Paintings, Drawings and Prints up to the Nineteenth Century, Leiden (Brill) 2020.

9

Berardi, M., Science into Art: Rachel Ruysch’s early development as a still-life painter (PhD), Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh) 1998.

10

See Alen, Klara, Margaretha Haverman (Breda, 1693/94 – Bayonne (?), na 1722): schilderend tussen passie en flora, Leuven (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven), 2010 and Hessel, Katy, The Story of Art Without Men, Dublin (Penguin Random House) 2022.

Romy Kerkhof is an art historian who specializes in Dutch eighteenth-century women artists. A graduate of the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, she holds a BA in Media, Art, Design and Architecture and is currently enrolled in the RMA Arts of the Netherlands program at the University of Amsterdam. In 2021, she worked at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam as a research intern, where she wrote several advisory reports that were key to enhancing the visibility of women artists in the Rijksmuseum’s collection.

Romy Kerkhof, "Unveiling Artistic Pathways: The Labour of Dutch Women Artists in the Eighteenth Century.." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/des-parcours-a-reveler-sur-les-traces-dartistes-neerlandaises-du-xviiie-siecle/. Accessed 14 July 2025