Research

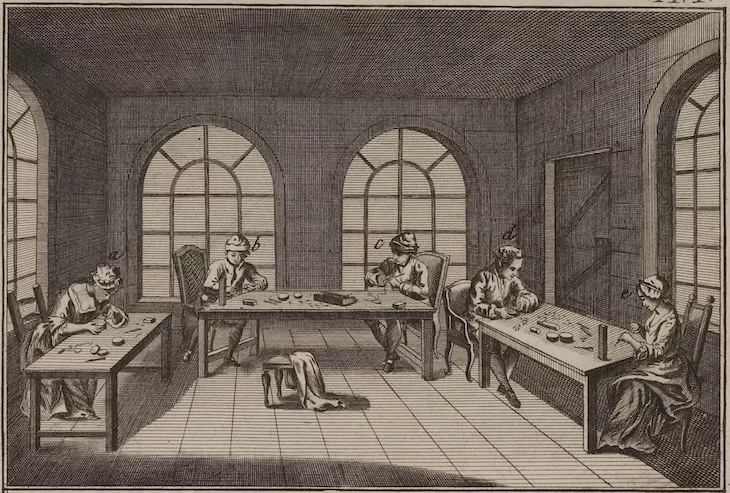

Thumbnail of plate 1: Snuffbox picker, volume IX of the illustrations of the Encyclopedia of Diderot, d’Alembert and Jaucourt, © Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

‘The study of history leaves us with uncertainty about individuals.’

Marcel Schwob, Vies imaginaires

In the foreword to the re-release of his book on the people of Paris, historian Daniel Roche reiterates the importance of taking an interest in the ‘nameless multitudes’ of history,1 a way of adding nuance not only to ideas that are often overly generalised but also to established stereotypes that are recycled without question. Women working in the sphere of the ancien régime guilds happen to belong to this category. Many studies have since renewed our way of seeing the history of social categories, and the past thirty years have brought a wealth of research on women.2 The authors of these studies have focused on tracking traces of these women in the historical records and shining a light on their stories. As historian Dominique Godineau points out, the risk of writing a ‘female’ history as precarious as the traditional ‘male’ history was great, and today, the history of women is considered part of gender history, a legacy of American studies on gender, which should not, however, be perceived as a theory but as an analytical tool.3 There is therefore no shortage of scholarly work on the status of women or their place in society and the working world.

It has been noted, however, that when it comes to artisanal trades, and the luxury sector in particular, no studies mention whether women – wives, daughters, sisters or widows of craftsmen – had any role in the production of goods. Eighteenth-century French society allowed the genders to mix, but there were inequalities. While there is no question that women’s legal inferiority was part and parcel of this society’s functioning, this does not mean that women were completely subjugated or had no scope for action. Most women accepted the situation, and some turned it to their advantage. How, then, were the responsibilities distributed in artisanal trades?

I will not attempt, in this short essay, to give any definitive answers regarding women’s place and role in trade guilds. Instead, I will examine a few select trades to offer some avenues for further reflection that may inspire more in-depth research. I will keep my focus narrow by excluding trades in the textile sector – the main source of work for women – as well as those connected to domestic tasks and smaller trades related to commerce and the food industry, which vie for second place amongst women’s jobs. Since many trades were not organised into communities, we have no official documents clarifying their statuses and rules. For this reason, I will restrict myself to a few professions organised by guilds.4 Finally, it goes without saying that a woman’s situation depended to an enormous extent on whether she was married (with or without children), unmarried (above or below the age of majority) or a widow, the most recent studies suggesting the importance of such differences.5 Similarly, it must be admitted that women are less visible in the documents available to us. They only rarely feature in printed sources and, because they were not recognised legally – with the exception of widows, to a limited extent – they must be searched for in the judicial archives and police reports. But they are there. Let us see how and to what extent, in this highly specific luxury trade milieu, we can make them more visible.

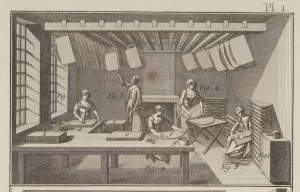

Thumbnail of plate 1: Fan maker, collage and preparation of the Papers, volume IV of the illustrations of the Encyclopedia of Diderot, d’Alembert and Jaucourt, © Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

Text and images

Recent studies have attempted to bring out a more nuanced version of the image put forward by two books that have long been the basis for all research on trades: Étienne Boileau’s Livre des métiers (c. 1268) on the professions and trade guilds of Paris, and theDictionnaire universel de commerce (1723) by Jacques Savary des Bruslons.6 For a few points of reference, let us look at some figures supplied by Natacha Coquery. In the eighteenth century, there were six merchant groups, including the goldsmiths’ guild, which we will explore, and 118 communities recognised by letters patent, as well as seventeen communities without letters patent. Of these 124 guilds, only five were exclusively for women.7 Of the seventeen others, four were for women and one was mixed-gender. However, Coquery does point out that other trades are mentioned in the pages of the Dictionnaire universel de commerce, which in some cases lists the men’s guilds first and then the women’s. And I have found that the presence of women can sometimes be discovered in its entries devoted to merchandise. For example, in the éventailliste entry,8 which specifies that it is ‘the fan-makers themselves, and their wives, daughters or female employees who apply the silver to the paper’, we have proof that women were involved, which of course does not mean that men were not. Thus, even when a trade is described as a profession for men, we can see that many women may have played an active role as well.

Let us now look at the illustrations in the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers by Diderot, d’Alembert and Jaucourt, again in the fan-maker’s trade.9 Three illustrations depict the work of this profession. The first shows the interior of a workshop in which the fan papers are glued and prepared. Five women working there are described variously as ‘gluer’, ‘raiser’, ‘spreader’, ‘cutter’ and ‘rounder’. The second depicts a room with space for two workers; a woman, busy painting a sheet of paper, is the only person shown. Finally, in the third, two women are assembling fans.

Other examples also exist.10 Let us examine one more – the entry for argenteur or silver-plater, whose sole illustration depicts four men and one woman.11 However, there is a contradiction between the image and the caption, which reads ‘two women burnishing an item’ although only one woman is shown in the scene. This is a good reminder that we must exercise caution when using illustrations from the Encyclopédie. Although it contains many such inconsistencies, its illustrations nevertheless prove that women were involved in certain trades, even though it always uses the masculine form of a position as the trade’s name.

To return to the woman depicted burnishing a silver piece, the position of brunisseuse (female burnisher) is frequently mentioned amongst the trades involved in metalworking for the production of luxury items. Several posthumous inventories of master goldsmiths12 list female burnishers amongst the creditors.13 Some are clearly married, one being the wife of a saddle-maker and merchant, while another is a widow. Another profession that appears regularly is polisseuse (female polisher), again in the goldsmith-jeweller’s trade.14 However, these deeds show only that sums of money were due. They do not reveal how large a role these women were given in the creative process or production. A contract signed by the master goldsmith Jean-Baptiste-Charles Clérin and twenty-one-year-old Marguerite Levasseur confirms the young woman’s role as allouée in his workshop’s production, the goldsmith committing to teach her how to ‘polish gold and silver and all sorts of jewels’.15

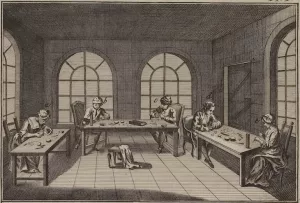

Thumbnail of plate 1: Goldsmith Jeweler, volume VIII of the illustrations of the Encyclopedia of Diderot, d’Alembert and Jaucourt, © Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

Nicolas de Largillière, Portrait de Thomas Germain orfèvre et de son épouse Anne Denise Gauchelet, 1736, oil on canvas, 161 × 130 cm, Callouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisboa

Tablet case, gold and Martin varnish, Louvre (OA 10644), corresponding to the type of production coming out of the Martin workshops, © 2007 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Martine Beck-Coppola

The art object: collaborative creation

When studying an art object, a historian must contend with the complication of such items rarely being the work of a single person. The obligations resulting from certain guilds – such as that of carpenter- cabinet-makers’ stamp strikers starting in 1637, then that of the jurande-stamp strikers in 1743, and goldsmith-jewellers’ stamp strikers, including the masters’ stamps – may cloud our perception of individuals’ roles. The master’s name is the only one recorded, very often overshadowing the man – or woman – whose work is responsible for the item’s quality. One example can be seen in chairs stamped with the carpenter’s name while the worker who did the actual carving, necessarily someone other than the carpenter, remains anonymous. Although guild statutes describe trades as organised around a master, who would distribute the work amongst his journeymen and apprentices, they never mention the presence of wives, daughters or sisters. But here again, some information can nevertheless be gleaned from various documents.

The first illustration that the Encyclopédie devotes to the goldsmith-jeweller’s trade shows five men busy with various tasks ‘whilst the maîtresse at the counter weighs and sells the merchandise’. Here, the term maîtresse (mistress) can only be understood as ‘mistress of the house’, in other words the master’s wife, since women were not allowed in the goldsmiths’ guild, apart from the rare exceptions made for master goldsmiths’ widows. However, there is evidence that women were involved in the activities of workshop-boutiques, even if only for certain finishing tasks, as we have seen with the woman working as an allouéefor the goldsmith Clérin. But they were also often involved in a workshop’s management, performing tasks we would today call ‘administrative’. A goldsmith’s wife or daughter may thus have been responsible for the keeping of various record books, noting purchases of old tableware that would be melted down as well as orders received, dispatches of ingots for refining, objects to be repaired, sales, and visits to and from the guild office and the mark office for the payment of fees. The portrait of the goldsmith Thomas Germain by Nicolas de Largillière depicts him surrounded by various items he has created and in the company of his wife, whose right hand rests on a stack of record books, clearly indicating her full involvement in this part of the goldsmith’s business16. The goldsmith Edme-Pierre Balzac, a widower, involved his daughter in the running of his workshop. It was she who, one day, received visiting representatives of the guild, who discovered the absence of stamps on pieces the workshop was then creating, and she who dealt with the matter from start to finish.17

Yet wives and daughters were not always limited to these administrative concerns – they sometimes also played an active role in the creation of objects. In 1736, the varnisher Guillaume Martin founded a company with his younger brother named Julien.18 The deed indicates not only that Julien agreed to spend ten years working for Guillaume, painting and varnishing items his brother would supply to him, but also that his wife, Marie-Anne Frion, and their daughter, Claude Hortense Martin, would also be in his employ. Although the deed unfortunately does not give any details about the work to be performed, Julien’s posthumous inventory reveals that a large part of his work involved making ‘lacquer jewels’.19 We also know that on 10 May 1713, Guillaume Martin hired two young women as allouées and began teaching them to polish the varnished objects he made. On 12 January 1739, he signed an agreement with Guillaume Daumont, a jewellery puncher, in which Daumont and his wife committed to working in Martin’s workshop for three consecutive years.20 Women clearly contributed to the physical production of items made in the famous varnisher’s workshop – but apparently only handling specific tasks that have not yet been fully identified.

Snuffbox, Louvre (OA 7665), © 2018 GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle

Snuffbox, Louvre, detail (OA 7665), © 2018 GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Stéphane Maréchalle

Snuffbox, Louvre (OA 6831) , © 2006 GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Snuffbox, Louvre (OA 6831) , © 2006 GrandPalaisRmn (musée du Louvre) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

The special case of widowsLet us now turn to the case of widows, bearing in mind that their status could vary greatly from one profession to the next.21 As a general rule, no longer being the dependent of a husband, a widow acquired full legal capacity, which meant she could sign civil law contracts, enter into agreements and take legal action. Furthermore, she had control over her possessions and could sell or donate them and draw up a will. But in practice, a widow’s freedoms were relative and depended on her marriage contract – in the artisanal milieu, the most common settlement was joint ownership of property.

Most guilds made mention of widows in their articles of incorporation. In the goldsmith-jewellers’ guild, this document refers to a ‘Special Title’22 authorising widows to hold the position of goldsmith as long as they did not remarry and also complied with the statutes and regulations. In such a case, they were required to destroy the stamp of their late husband and to mark their creations with their own stamp, which would include the letter ‘V’ for veuve to indicate their status as widow. In 1679, undoubtedly due to fraudulent use, this right was taken away and widows were henceforth required to have their creations marked by another master who served as the guarantor of their work. However, a discrepancy between reglementary theory and practices born out of necessity can be observed, the case of the goldsmith Jean George being one example.

The Musée du Louvre owns ten snuffboxes produced by his workshop between 1756 and 1781. Three were made by the goldsmith himself and bear his stamp and an inscription, engraved along the front inner rim, reading: ‘George AParis’. George died in 1765, leaving behind a journeyman, Pierre-François-Mathis de Beaulieu, and an apprentice. His widow, Jeanne-Françoise Texier, took over the workshop, as her status allowed her to do. A snuffbox dated 1765 bears the inscription ‘VE GEORGE A PARIS’ on its front inner rim, as well as George’s stamp, while another dated 1767–1768 is marked only with George’s stamp, indicating that in spite of the regulations, his widow continued to use her husband’s stamp. In 1768, her journeyman concurrently moved up to the rank of master and she married him. From that point on, the snuffboxes produced by this workshop were marked with Pierre-François-Mathis de Beaulieu’s stamp. Amongst those in the Louvre’s collection is one inscribed ‘Ve George Beaulieu’ and another ‘Ve George Beaulieu à Paris’, which suggests that Jeanne-Françoise still actively contributed to the production. One last snuffbox is engraved only with ‘Beaulieu A Paris’, showing that it is his work alone. As this case can be interpreted in different ways, however, it is clear that many situations still escape our full understanding. During her three years of widowhood, Jeanne-Françoise Texier probably allowed Beaulieu to complete his journeymanship. By marrying him, she ensured the workshop’s continuity. We will never know what her motivations were, or whether she took an active part in the production in addition to managing the business.

Things were altogether different for Pierette Candelot, also known as Widow Perrin. Natives of Lyon, her parents settled in Marseille to start a business producing silk fabrics. In 1736, she married Claude Perrin, an earthenware-maker. In their marriage certificate, he acknowledged receipt of 1200 livres that his bride had saved through her labour and industriousness – an interesting detail showing that young Pierette had worked before her marriage, although we do not know whether this was in textiles or under another earthenware-maker. On 25 March 1748, Perrin died very suddenly, leaving behind three underage children, debts and a failing business. With her status as widow, Pierette Perrin was able to take the affairs of the manufacture in hand, all deeds henceforth being signed ‘Widow Perrin’. She took on apprentices and taught them the trades of earthenware-maker, potter and painter, undoubtedly already skilled in these techniques herself. Various deeds show that she continually managed the business, enlarging the workshop spaces and forming new companies, partnering either with other manufacturers or with her eldest son. In 1783, forced to declare bankruptcy, she convinced the judges to allow her to start her business anew. She died on 21 November 1794, aged eighty-five.23 Widow Perrin’s story shows that with determination, an enterprising woman could build a good reputation for her manufacture. By maintaining her status as widow, she was able to ensure that the family business endured.

Plate from the royal manufacture of Sèvres, painted by Antoinette-Marie Noualhier in 1786, Louvre, face (TH 962), © 2024 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Michel Bourguet

Plate from the royal manufacture of Sèvres, painted by Antoinette-Marie Noualhier in 1786, Louvre, back (TH 962), © 2024 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Michel Bourguet

In the shadows of the manufactures

What of the women employed at a manufacture, a workspace that differed from that of the family workshop, which also served as a living space? Let us look at the example of the Manufacture Royale de Porcelaine de Vincennes-Sèvres, whose copious archives enable a thorough understanding of its production history. However, some gaps in the documents from the eighteenth century make it difficult to determine the role occupied by women, whose presence is nevertheless attested by the marks painted on the backs of the pieces. Of the 436 painters and gilders whose marks have been partially identified for the eighteenth century, only 71 are women, most of them wives, widows, daughters, daughters-in-law or sisters of a worker employed at the manufacture.24Most of them were painters, often specialising in floral motifs. Some were burnishers and repairers, while others were assigned to making flowers, a task handled only by women.25 Their presence in a mixed-gender work setting suggests that all the employees had equivalent levels of responsibility and know-how, and that the women excelled at their work to the same degree as their male counterparts. Further research on the women working at the manufacture would undoubtedly bring this female talent out of the shadows.

Research at a stalemate

Although for decades art history has focused solely on the men in the luxury artisanal trades, we know that women too had a hand in this production of past centuries. It should be noted that the discrepancies between the reality of women’s work, known in part due to mentions gleaned from the archives, and the theory have stalemated our knowledge of it to some extent. Because they were deemed to have no legally capacity unless widowed, women were excluded from the main trade guilds and communities associated with luxury artisanal production. Yet they were active in it. The biggest challenge lies in identifying those who participated in the actual production. Although a woman clearly could not choose to become a full-fledged goldsmith, cabinet maker or chiseller, some women did contribute to the success of specific creations made by a master, who placed his mark on them. On an exceptional basis, the signature that painters, sculptors and miniaturists would place on their creations – albeit not systematically – allowed them to leave the anonymity of their workshop (such as the system of marks used by the Vincennes-Sèvres manufacture), although without giving them full visibility. Tracing the individual journeys of these women working in masters’ workshops or in chambers seems nearly impossible. In an artisan’s workshop, parents, children, journeymen, apprentices and servants of both sexes would most often live and work together, a situation that facilitated women’s participation in the business and made it thinkable for girls to acquire practical expertise or even techniques that put them behind a counter or a workbench once they were married. Without better knowledge of these workshops’ day-to-day operations, we will undoubtedly have to settle for forming hypotheses based on common sense, failing which our modern perceptions could betray the historical reality. More in-depth studies of the various trades examined in this essay are needed to shine a light into the shadows surrounding the roles women played.

An expression borrowed from Alf Lüdtke. See Roche, Daniel, Le Peuple de Paris. Essai sur la culture populaire au XVIIIe siècle [1981], Paris: Fayard, 1998, p. iv.

2

Bibliographic references are provided in the notes. They represent just a small selection of the studies elucidating the place of women in ancien régime guilds, to which the following may be added: Beauvalet-Boutouyrie, Scarlett, Les femmes à l’époque moderne, (XVIe-XVIIIesiècles), Paris: Belin, 2003; Bellavitis, Anna, Women’s Work and Rights in Early Modern Urban Europe, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018; Farge, Arlette and Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane (eds.), Madame ou Mademoiselle ? Itinéraires de la solitude féminine XVIIIe-XXe siècles, Paris: Arthaud-Montalba, 1984; Groppi, Angela, ‘Le travail des femmes à Paris à l’époque de la Révolution française’, Bulletin d’histoire économique et sociale de la Révolution française, Paris: Société des Études Robespierristes, 1979, pp. 27–46; Juratic, Sabine and Pellegrin, Nicole, ‘Femmes, villes et travail en France dans la seconde moitié du XVIIIe siècle’, Histoire, économie et société, Paris: L’Harmattan, 1994, no. 3, pp. 477–500; Potvin, Christèle, ‘Les archives des corporations d’arts et métiers sous l’Ancien Régime et le travail des femmes’ in Tout ce qu’elle saura et pourra faire, Femmes, droit, travail en Normandie du Moyen Âge à la Grande Guerre, Femmes au travail en Seine-Maritime collective volume, Paris: Les Éditions du Cygne, 2015, pp. 43–56; Sheridan, Geraldine, Louder than Words: Ways of Seeing Women Workers in Eighteenth-Century France, Lubock: Texas Tech University Press, 2009.

3

Godineau, Dominique, Les Femmes dans la France moderne, XVIe-XVIIIe siècle, Paris: Armand Colin, Coll. U, 2015. See also the contrasting perspectives of six historians in ‘Genre, travail et cité’, Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 2018/4, no. 394, pp. 129–154.

4

See the fascinating study by Mathieu Marraud, ‘Corporatisme, métiers et économie d’exclusion à Paris, XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles’, Revue historique, 2019/2, no. 690, pp. 283–313, the work of Steven L. Kaplan, ‘L’apprentissage au XVIIIe siècle: le cas de Paris’, Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine, 40/3, Paris: Société des études robespierristes, 1993, pp. 436–479 and La fin des corporations, Paris: Fayard, 2001; and Cynthia Truant, ‘La maîtrise d’une identité ? Corporations féminines à Paris aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles’, Clio, Histoire, femmes et sociétés, 1996 /1, no. 3, pp. 4–12, Paris: Éditions de l’EHESS.

5

See Beauvalet-Boutouyrie, Scarlett, Être veuve sous l’Ancien Régime, Paris: Belin, 2001; Godineau, Dominique, Les femmes dans la France moderne, XVIe-XVIIIe siècle, Paris: Armand Colin, Coll. U, 2015 [reference absent from the bibliography because this is the version reprinted in 2015]; Juratic, Sabine, ‘Solitude féminine et travail des femmes à Paris à la fin du XVIIIe siècle’, Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Moyen Âge, temps modernes, vol. 99, no. 2, 1987, pp. 879–900; Lanza, Janine, From Wives to Widows in Early Modern Paris: Gender, Economy, and Law, England: Aldershot, Ashgate, 2007 and ‘Les veuves dans les corporations parisiennes au XVIIIe siècle’, Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine, 2009/3, no. 56-3, pp. 92–122; Pellegrin, Nicole and Winn, Colette H. (eds.), Veufs, Veuves, Veuvages dans la France d’Ancien Régime, proceedings of the Poitiers Colloquium, 11–12 June 1998, Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 2003.

6

Coquery, Natacha, ‘Norme, genre, taxinomie. Désigner les métiers: le Dictionnaire universel de commerce de Savary des Bruslons’, in Gilbert Buti, Michèle Janin-Thivos and Olivier Raveux (eds.), Langues et langages du commerce en Méditerranée et en Europe à l’époque moderne, Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence, 2020, pp. 255–274; Crowston, Clare Haru, ‘L’apprentissage hors des corporations. Les formations professionnelles alternatives à Paris sous l’Ancien Régime’, Annales, Histoire, Sciences sociales, 2005/2, sixtieth anniversary issue, pp. 409–441.

7

These women specialised in hairdressing, sewing, the production and sale of linens and fabrics, the sale of flax, hemp and tow, and midwifery.

8

Savary des Bruslons, Jacques, Dictionnaire universel de commerce, 1742, vol. 3, p. 335 and ff.

9

Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. IV of the plates, éventailliste entry.

10

See aiguillier-bonnetier (needlemaker-bonnet-maker), batteur-d’or (gold hammerer), ciseleur-damasquineur (chiseller-inlayer), doreur sur bois (wood gilder), émailleur à la lampe et peinture en émail (torch enameller and enamel painter), orfèvre bijoutier (goldsmith-jeweller), piqueur en tabatières (snuffbox puncher), incrusteur (embedder), brodeur (embroiderer), tabletier (tablet maker), cornetier (horn worker) andtireur et fileur d’or (gold-thread maker).

11

Encyclopédie…, vol. I, ‘Argenteur’ (silver-plater) entry.

12

I thank Yves Carlier for sharing his research and documents with me.

13

French National Archives (hereafter, ‘FNA’), Notary Minutes Department (hereafter, NMD), office LXXXVIII, 652, 14 July 1759; LVI, 209, 9 May 1776; XLVIII, 124, 14 May 1705; XIII, 305, 7 September 1757; CXXII, 712, 30 June 1760.

14

FNA, NMD, IX, 676, 21 January 1751; IX, 687, 19 April 1755; Y 1888, 19 December 1772; and Paris Archives, D4 B6, box 29, dossier 1565.

15

FNA, NMD, XCVII, 302, 17 October 1744. An alloué learns a trade from a master, depending entirely on the master, and can remain at this status throughout his life. He is not an apprentice who can eventually become a journeyman.

16

Upon her husband’s death, Madame Germain formed a partnership with their son, François-Thomas Germain. The deed specifies that she handled only management tasks, leaving the goldsmithing to the son. Perrin, Christiane, François-Thomas Germain, orfèvre des rois, Saint-Rémy-en-l’Eau: Monelle Hayot, 1993, p. 19.

17

Arquié-Bruley, Françoise, ‘Problèmes des orfèvres au XVIIIe siècle. Les frères Balzac’, Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, 1987 (1989), p. 98.

18

FNA, NMD, office XXX, 267, 27 October 1736.

19

Kopplin, Monika and Forray-Carlier, Anne, Les Secrets de la laque française. Le vernis Martin, Paris: Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2014, pp. 46–48 and 123–131.

20

FNA, NMD, office XXVIII, 123 and XXXVIII, 302.

21

On the purely legal considerations of the legislation applicable to widows, see Poumarède, Jacques, ‘Le droit des veuves sous l’Ancien Régime (XVIIe–XVIIIe siècles) ou comment gagner son douaire’, in Itinéraire(s) d’un historien du droit. Jacques Poumarède, regards croisés sur la naissance de nos institutions, Toulouse: Presses universitaires du Midi, 2020, pp. 217–225; on the artisanal milieu, see Beauvalet-Boutourye, 2001, op. cit. and Lanza, 2009, op. cit.

22

See Pierre Leroy, Statuts et privilèges du corps des marchands orfèvres-joailliers de la ville de Paris [1734], 1759, title VIII.

23

Maternati-Baldouy, Danielle, ‘Historique de la manufacture Pierette Candelot-Claude Perrin’, in La Faïence de Marseille au XVIIIe siècle. La manufacture de la veuve Perrin, Marseille, Centre de la Vieille Charité, 1990, pp. 32–50. For other women at the head of a workshop, see also: Chassagne, Serge, Une Femme d’affaires au XVIIIe siècle: la correspondance de Madame de Maraise, collaboratrice d’Oberkampf, Toulouse, 1981; Desjardin, Camille, Madame Blakey, une femme entrepreneure au XVIIIe siècle, Mnémosyne, PUR, 2019; Dousset, Christine ‘Commerce et travail des femmes à l’époque moderne en France’, Les Cahiers de Framespa [online], 2 | 2006, uploaded 1 October 2006, accessed 16 July 2024.

24

Peters, David, Decorator and Date Marks on 18th Vincennes and Sèvres Porcelain, © David Peters, 1997 (version accessed).

25

Préaud, Tamara and Brunet, Marcelle, Sèvres, des origines à nos Jours, Fribourg: Office du Livre, 1978 and Préaud Tamara and d’Albis Antoine, La Porcelaine de Vincennes, Paris: Adam Biro, 1991, p. 52.

26

Préaud, Tamara et Brunet, Marcelle, Sèvres, des origines à nos Jours, Fribourg, Office du Livre, 1978 et Préaud Tamara, d’Albis Antoine, La Porcelaine de Vincennes, Paris, Adam Biro, 1991, p. 52.

After completing her studies in art history at the Ecole du Louvre, the University of Paris IV Sorbonne and the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Études, Anne Forray-Carlier was accepted as a curator for the French public institutions. She successively held the position at the Carnavalet Museum, at the Museum of Decorative Arts, where she was deputy director from 2019 to 2023, and currently in the Department of Decorative Arts at the Louvre. She is the author of several books devoted to decorative arts, and has also collaborated and curated several exhibitions.

Anne Forray-Carlier, "Being a woman in the trade guilds of eighteenth-century France." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/etre-femme-dans-le-milieu-corporatiste-des-metiers-de-lartisanat-en-france-au-xviiie-siecle/. Accessed 27 February 2026