Review

Germaine Richier, L’Échiquier grand, 1959, bronze, variable dimensions, Indivision Germaine Richier, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/ Dist.RMN-GP, © ADAGP, Paris

This summer Mont-Saint-Michel welcomes the works of one of the queens of metamorphosis: Germaine Richier (Grans, 1902–Montpellier, 1959). Ariane Coulondre, the organiser of the exhibition together with the Centre des monuments nationaux as part of the 40th-anniversary celebrations of the Centre Pompidou1 , provides a short but intense presentation of works. The particular highlights – on the abbey square and beneath the Gothic arches in the Salle des hôtes – retrace the artist’s research from the end of World War II until her death.

Germaine Richier, L’Ouragane, 1948–1949, bronze, 179 x 67 x 50 cm and L’Orage, 1947–1948, bronze, 200 x 80 x 52 cm, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/ Dist.RMN-GP, © ADAGP, Paris

After a solid classical training (at the école des beaux-arts de Montpellier, then in the workshop of Antoine Bourdelle) and a rather conventional practice between the wars, as from 1945 Germaine Richier freed herself of all the codes then in force to produce hybrid figures that blend figuration and abstraction, human and animal form, using a technique that combined modelling and found objects. In an essentially male world, she succeeded in forging a solid reputation for herself thanks to her daring. For example, she persisted in sculpting from a live model. Two important works in the exhibition – L’Orage (1948–49) and L’Ouragane (1947–48) – were produced using this technique and bear witness, before Alberto Giacometti’s L’homme qui marche and Femmes de Venise, to the relevance of the persistence of figuration during this period when abstraction seemed to triumph. Richier stated, “I am the opposite of the abstract but the laws of abstraction are of great importance to me”.2 She chose her titles from reality: La Montagne (1955–56), L’Eau (1953–54), Le Diabolo (1950), L’Échiquier, grand (1959/2004), etc. Following in the Surrealist tradition and anticipating the work of both the Pop and Nouveaux Réalistes artists,3 she included elements taken from the real world in her works: branches in La Montagne, an amphora found on the beach for L’Eau, and so on. However, her formal and geometric concerns remain visible. In Le Diabolo, which is representative of the series of Fils, the metallic wires create silhouettes of intangible volumes between the body and base. The wires in question are both structural lines in the composition and a metaphorical reference to the threads of fate.

Germaine Richier, La Montagne, 1955–1956, golden patina bronze, 185 x 330 x 130 cm, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/ Dist.RMN-GP, © ADAGP, Paris

Germaine Richier, L’Échiquier grand, 1959, bronze, variable dimensions, Indivision Germaine Richier, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/ Philippe Migeat/ Dist.RMN-GP, © ADAGP, Paris

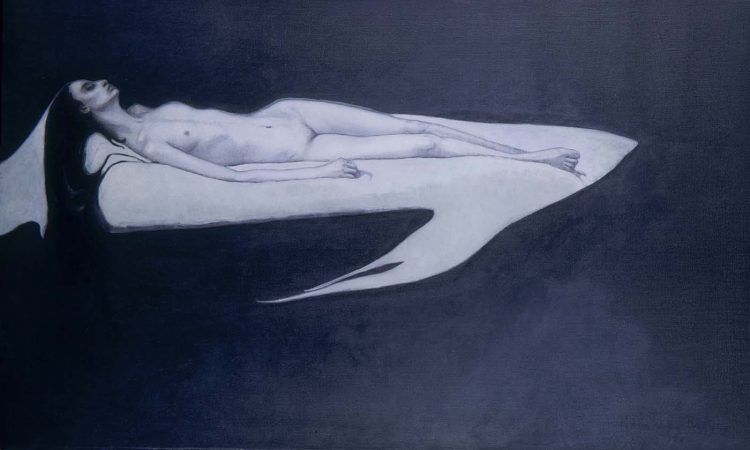

Her figures confirm her subjectivity: they are amputated (L’Eau is headless), deformed (the queen in the L’Échiquier, grand “raises rod-arms”, the Ouragan–Man holds himself frozen as though he had been caught in the lava of Pompeii), and reinvented (La Montagne suggests a mysterious confrontation). Their metamorphoses evoke the existentialist thought that was then current among Parisian intellectuals: our existence here is uncertain, our knowledge of it is incomplete, the human condition is unable to shrug off the tragic. With her experiments, Germaine Richier attempts to contribute to the redefinition of a post-Holocaust form of humanism.

Her sculptures naturally create a dialogue with their surroundings: the magnificent architecture of the abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel and the outstanding setting of the bay. The five black, specific figures in the L’Échiquier, grand stand out against the greenish-grey of the silt behind. L’Eau, installed in front of the windows of the Gothic Room, seems to be leaning against a throne of light. Throughout the presentation, the artist’s powerful and sensual figures alter how we look at the monument and landscape.

Frédéric Paul, conservator of the contemporary collections at the musée national d’Art moderne, has coordinated forty celebratory events across France.

2

Germaine Richier, Paroles d’artistes : Germaine Richier, Paris, Fage, 2017, p. 46.

3

César acknowledges her influence. Cf. Michèle Cone, “The Mature Richier, the Young César: Expressionist Confluences in French Postwar Sculpture”, Art Journal, vol. 53, no 4, “Sculpture in Postwar Europe and America, 1945–1959”, Winter 1994, pp. 73-78.