Germaine Richier

Germaine Richier, exh. cat., Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne (10 October–9 December 1956), Paris, Éditions des Musées Nationaux, 1956

→Prat Jean-Louis (ed.), Germaine Richier : rétrospective, exh. cat., Saint-Paul de Vence, Fondation Maeght, (5 April–25 June 1996), Saint-Paul, Fondation Maeght, 1996

→Da Costa Valérie, Germaine Richier: un art entre deux mondes, Paris, Norma, 2006

Germaine Richier, l’ouragane, Abbaye du Mont-Saint-Michel, Le Mont-Saint-Michel, 1st July–12 November 2017

French sculptor.

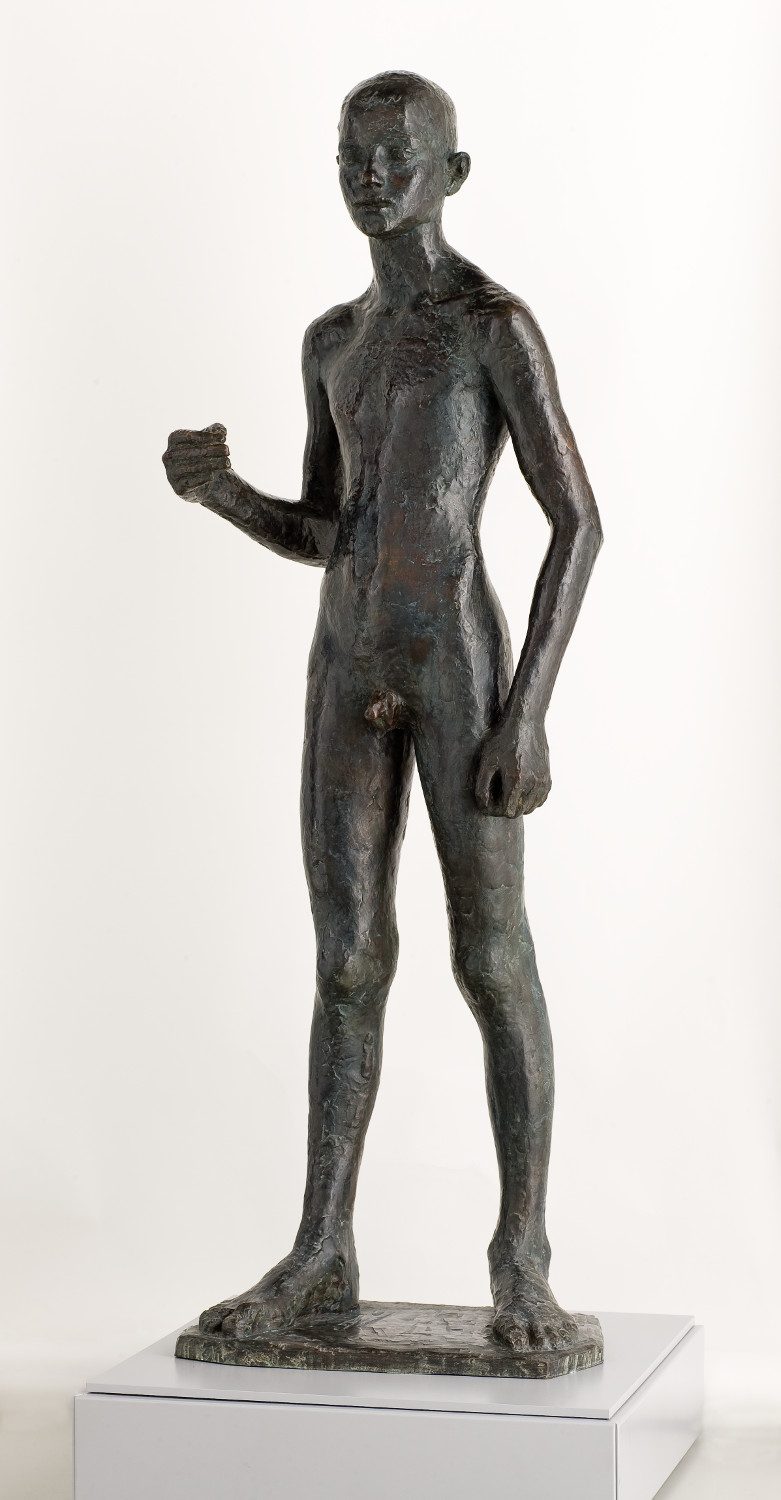

Germaine Richier began to study sculpture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montpellier in 1920, in the studio of Louis-Jacques Guigues, a former assistant of Rodin. Then, in 1926 she worked under Antoine Bourdelle in Paris until his death. In 1929 she married Otto Bänninger, a Swiss sculptor and an assistant of Bourdelle. Between 1930 and 1933 she made 8 nudes and 26 busts. Faithful to figuration, she reinterpreted human forms and the base on which her works were placed. She reduced to bareness the space of the sculpture, emphasizing the effects in the material and artifices of the structure, thereby integrating the base in the work. She quickly made a name for herself, a fact that brought her pupils. On a trip to Pompeii in 1935, she was very struck by the petrified human figures. The following year the Galerie Kaganovitch gave her her first exhibition. She won a number of prizes, amongst which the medal of honour for Méditerranée at the international exposition in Paris in 1937, and her work was included in the New York World’s Fair in 1939.

During the war she lived with her husband in Zurich, where she taught. The sculpture she made in 1940, Le Crapaud [The Toad], in which the title refers to the model’s pose, heralded a new aesthetic in her work, in which the animal, human and plant worlds are mixed. She also sculpted busts (La Chinoise, 1939) and nudes (Juin 40 : Pomone, 1945), which were more firmly rooted in reality. After exhibiting in Basel, Berne and then Zurich, she returned to her studio in Paris in 1946, restarted with her pupils and continued her work on hybrid figures. Scarified, her figures bore the wounds of the war – like Rodin and Bourdelle, the human element was at the centre of her creation – but also emphasized the corporal association of man with the earth and the animal kingdom. To make L’Orage [The Storm], 1947–1948, which was shown at the Venice Biennale in 1950, she took Libero Nardone (1867–1961) as her model (he had posed for Rodin’s Balzac as a young man), thus demonstrating her wish to take her place in figurative sculpture while also incorporating a stylistic break.

The Galerie Maeght organized a large exhibition of her work in Paris in 1948. An issue of the review Derrière le miroir was dedicated to her, in which articles were written by René de Solier, Georges Limbour and Francis Ponge. In 1949 she made a Christ for the new Church of Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce on the plateau d’Assy, which was removed in 1951 as the local population disapproved of the modernity of the work’s forms. This blunt rejection was probably linked to the fact that Richier was a woman, meaning, according to the religious orders, that she had no access to the dimension of the sacred. The sculpture would only be returned to its public place in 1971, whereupon it was classed as a historic monument. As from 1951, the year in which she won the First Sculpture Prize at the first São Paulo Biennale, she introduced colour into her bronzes: with a backdrop painted by Maria Vieira da Silva, La Ville [The Town], 1951 was the first example. In 1952 she sculpted La Toupie in collaboration with Hans Hartung. Wishing to break free from the yoke of the space and volumes, Richier also made engravings, which she showed regularly in exhibitions of prints. She also illustrated the poems of Rimbaud with etchings. Le Berger des Landes [The Shepherd from the Landes], 1951 and Le Griffu [Claws], 1952 continued her work using wires, which she had begun with L’Araignée I [Spider I] and then Le Diabolo (1950). In these, iron wires intersect one another in space, joining forms together and to the base of the sculpture. This expedient was less about showing movement than arousing it and presenting it in its fetters. She was included in the Venice Biennale in 1952 and in that of São Paulo in 1953, the year she produced La Tauromachie [The Bullfighting], La Fourmi [The Ant] and L’Eau [Water]. Her œuvre was largely shown abroad. She produced busts of Franz Hellens (1955) and André Chamson (1955), conceived small works made of lead, cuttlefish bones and plaques of wax, and continued to sculpt fantastic figures (L’Hydre, Hydra, c. 1954–1955). In 1956 a large retrospective of her works was held at the musée national d’Art Moderne in Paris, then she created Le Tombeau de l’orage [The Tomb of the Storm] and L’Ombre de l’ouragane [The Shadow of the Hurricane], her only sculptures in stone. In 1958 she illustrated Contre Terre, a collection of poems by René de Solier (her second husband, whom she married in 1954), and produced her last large coloured work, L’Échiquier [The Chessboard]. She just had the time to prepare her last exhibition at the Château Grimaldi in Antibes before her death in 1959.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Retrospective exhibition of Germaine Richier at galerie Odermatt-Cazeau in 1992

Retrospective exhibition of Germaine Richier at galerie Odermatt-Cazeau in 1992