Interviews

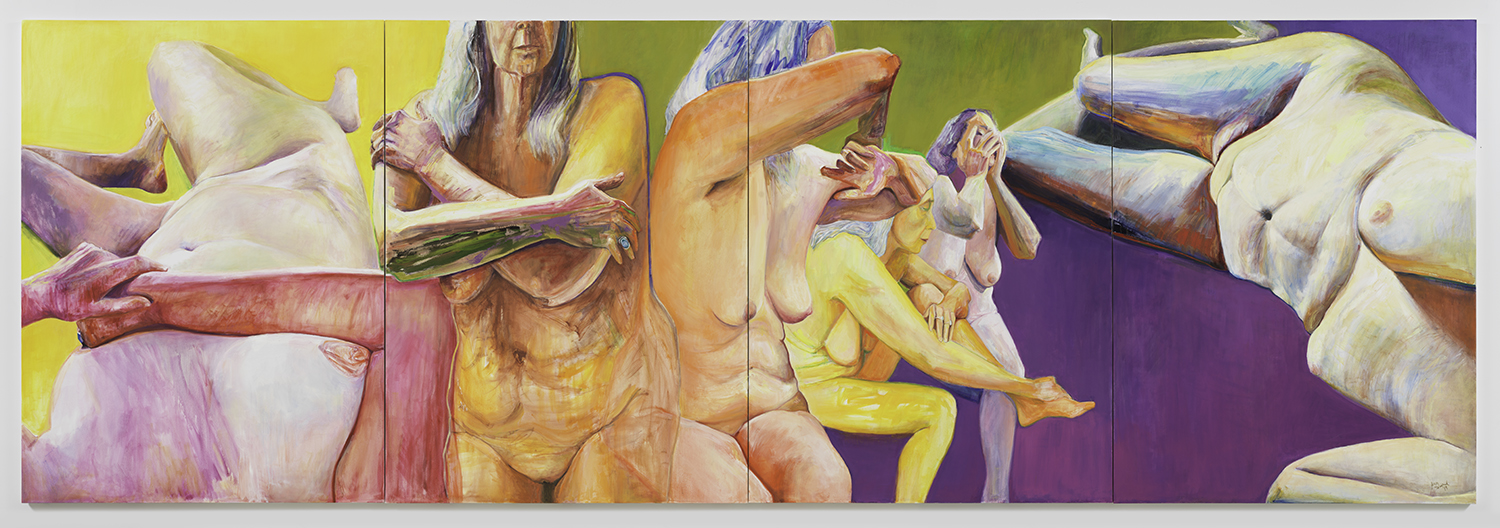

Joan Semmel, Skin in the Game, 2019, oil on canvas in 4 parts, 96 × 288 in. overall (243.84 × 731.52 cm), each 96 × 72 in. (243.8 × 182.9 cm), Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, © ADAGP, Paris

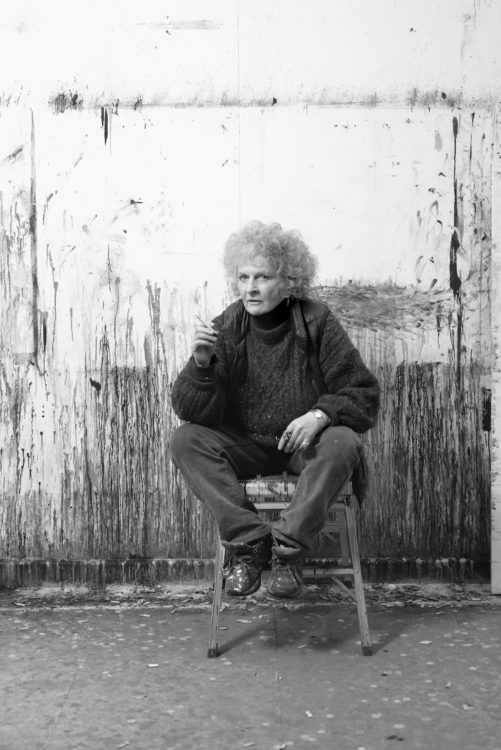

Joan Semmel is an American painter whose figurative work deals with the notions of intimacy and sensuality. She’s also known for her feminist involvement in the New York art scene since the 70s through her presence in groups such as the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee. Following her first retrospective in the United States in 2021, this interview highlights the evolution of her work since the 60s. Combining abstract expressionism to realism, J. Semmel first represented sexuality before focusing on the theme of aging with self-portraits.

Ewa Giezek: At the summer 2021, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia (PAFA) mounted your retrospective Joan Semmel: Skin in the Game (July 2 – August 21, 2021). The title of the exhibition references your painting of the same name in which you represent your own nude figure in six iterations across 4 canvases. The majorityof your work since the 1970’s are also self-portraits, or self-images of this kind. Why is it so important today to represent the truth and the beauty of ageing?

Joan Semmel: My work deals with ageing because I started to get older. One day, you look at the mirror and say “Who is that person? That’s not me anymore!” Those physical changes showed in my work, as well as in my personal life. During my career, I have been using self-image to illustrate my concerns with the representation of women in our culture. Today, I want to show that our culture has been so preoccupied with youth that the concerns of older people have been really passed over to a large degree even if ageing is just part of the human condition. I dealt with ageing as I dealt with my self-image all the way through, as honestly as I could.

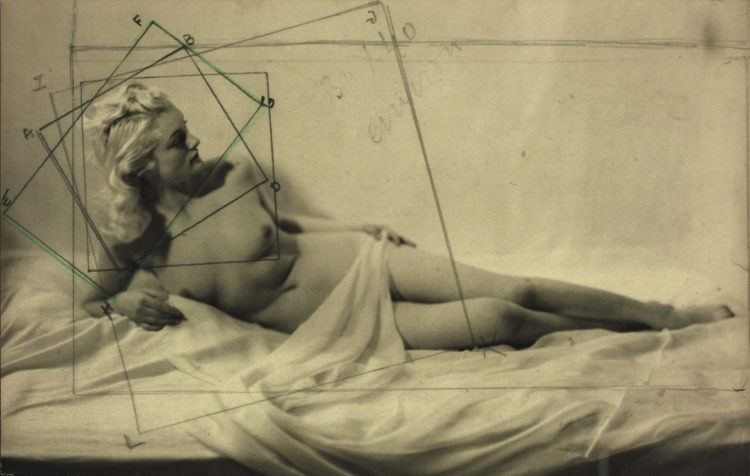

EG: Your self-images are painted from photographs of your body taken by yourself. As with Centered, 2022, the image represented is taken in front of a mirror which allows the viewer to see both the process and the means (the camera). Does this mode of representation allow you to confront the viewer’s gaze on ageing?

Joan Semmel, Centered, 2002, oil on canvas, 48 × 53 in. (121.92 x134.62 cm), Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, © ADAGP, Paris

JS: I liked the idea that the camera is pointed at the viewer. I have always been concerned with the idea of the objectification of women. In these paintings I’m saying, “If you are looking at me, here I am looking at you.” The painting is looking back at the viewer, which destabilised the point of view. Whose point of view is it? Yours or mine? The viewers or the person being viewed? It is a way to give agency to the viewed body, to allow the viewed body to bethe active rather than the passive subject. Nevertheless, critics often compared the composition of my paintings to photographs but I have never considered myself a photographer! I only use photographs as a tool to capture the images.

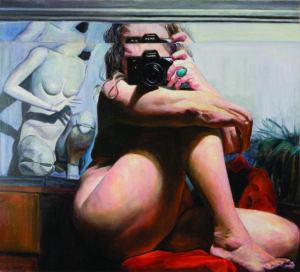

EG: In the 1960’s, before using photographs and the start of your producing figurative paintings, you spent close to a decade creating abstract canvases. Your career clearly shows your taste for clear and bright pictorial materials; what do you want them to bring to the topics you explore?

Joan Semmel, Purple Diagonal, 1980, oil on canvas, 78 × 104 in. (198.12 × 264.16 cm), Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, © ADAGP, Paris

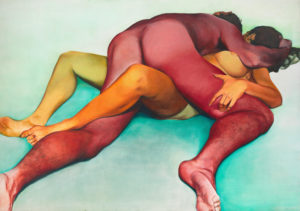

JS: The colours are the pleasure of paint to me. I respond to them emotionally and aesthetically. My choices are more sensual than intellectual. I want to spread joy, to celebrate sensuality. It is something essential to the sense of being human. When I left abstraction and started to focus on figuration with the Fuck Paintings to represent couples making love, I kept the high colours that I had used as an abstract expressionist. In order to say what I had to say, I wanted the images to resonate. Then my work gradually became more naturalistic in tones. But after many years of working that way, I moved back towards the high colours and a more active surface, like on Purple Diagonal. I felt that I was free again to be able to use painting colour totally because my content was already known and understood from the art world, so I didn’t need to emphasise it that much.

EG: Talking about the importance of being free to create as a woman artist, I would like to go back to the beginning of your figurative work, in the early 1970s. At that time you were shocked by the sexualised images of women in American visual culture. How did this shock translate into being the starting point for your Erotic Paintings?

Joan Semmel, Green Heart, 1971, oil on canvas, 48 × 58 in. (121.92 × 147.32 cm), Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, NewYork, © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NewYork, © ADAGP, Paris

JS: My understanding of my role as a woman and as an artist became much clearer to me during that period, because of my inability to enter the New York art world easily. I was already a feminist but I realised that there were other people with whom I could talk about my concerns, I joined groups like the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee, where Lucy Lippard was very influential. I was linked to other artists and I went to their studios; we all influenced each other during our meetings. It was very pluralistic but the common thread was the feminist revolution. I started to think about the possibility of women becoming members of society in a productive way. My feeling, as a young woman at that time, was that the problems began in the bedroom and needed to be addressed from this source. That was a part of why I moved into the sexual work. I felt that until a woman could have her own sense of her own sexuality and desire, she would never be an active member in the political structure. Pornography and the images of pin-ups were so prevalent at that time. It was advertised as a sexual revolution, but it was a sexual revolution for men and not for women, which was a very important distinction.

EG: Were your Erotic Paintings a way of creating more space for the sexual freedoms and expressions for women?

JS: I was interested in breaking down the prejudice in which sexuality was shameful for women. There was the idea that sexuality was dirty, that good women wouldn’t feel sexual desire. I started to wonder why women didn’t try to respond to the pornography made for men. The attitudes expressed in pornography were about power relationships, the power of the active men and the subjection of the passive women were always a part of the play. I wanted to show relationships where women and men had equal needs and desires. My behaviour was kind of revolution, as I have taken huge risks to do it as a woman. There was no concept of the “female gaze” at that time but I wanted to reflect in my paintings that the person making these works of art was a woman, and that it was through her eyes that the work must be seen. However, it was very difficult to show my work to the public at the beginning. Women artists were ostracised, we engaged in a lot of resistance. When the Guerrilla Girls came alive during the 1980s, we started to point out structural and institutional discriminations. We made posters and put them all over the city. These are great memories; it was a very exciting time. It was important to be in New York to participate in that kind of activity.

Joan Semmel, Perfil Infinito, 1966, oil on linen, 74 7/8 × 69 ¼ in. (190 × 175.9 cm), Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, © ADAGP, Paris

EG: You organised your first Erotic Paintings exhibition by yourself, renting the space, mounting the show and manning the gallery. And in 1975, your work was then part of an exhibition banned by the Supreme Court due to the show’s explicit male nudity. 43 years later, you were a part of an exhibition called In the Cut: The Male Body in Feminist Art (2018) at the Stadtgalerie Saarbrücken in Germany. Does this speak to an evolution in the way erotic works, or works depicting any nude bodies, in general and regarding your paintings in particular are now recognised in the art world?

JS: Censorship still exists in a certain way. The United States of America comes from a puritan background so anything sexual is still suspicious. Museums were worried about showing works of this kind. Commercially, it was almost impossible to sell during the 1970s. There were feminist exhibitions in galleries but I was even censored in those groups. In the Cut: The Male Body in Feminist Art is a much later show and honestly I think it was too centred on the male body. I was not interested in the idea of doing to male’s bodies the same thing male artists had done to women’s bodies. I don’t want to make anybody into a fetish or a doll, I don’t see the point of reversing abuse. Eroticism, for me, has to do with an interchange and with the sensitivity of touch, of sound and intellect. Eroticism is about connecting with another person and it is fine that now women have the freedom to respond to that physicality of men, or of another woman.

Joan Semmel, Hold, 1972, oil on canvas, 72 × 108 in. (182.88 x274.32 cm), Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, © ADAGP, Paris

EG: If we imagine a kind of fusion between your differing themes linked to eroticism/sensuality and then the ageing body, could you conceive of revisiting the Erotic Paintings using older models today?

JS: I don’t know what it looks like; I haven’t watched old people making love [laughs]! I think it would be difficult; we are so used to thinking of sexuality as being removed from the aged body. What would I be accomplishing in doing that? Giving people, or even myself, permission to be sexual? I didn’t want the male body to be a fetish object. There would be a parallel reason in the fact of being not interested in representing the ageing body having sex. I don’t want the older body to be fetishised either. The confronting of ageing and of all that it implies is always about the confronting of death, which is the contrary to the confronting of life, what sex is. I wouldn’t represent ageing dealing with sexuality because there are other issues in the understanding of the finality of life.

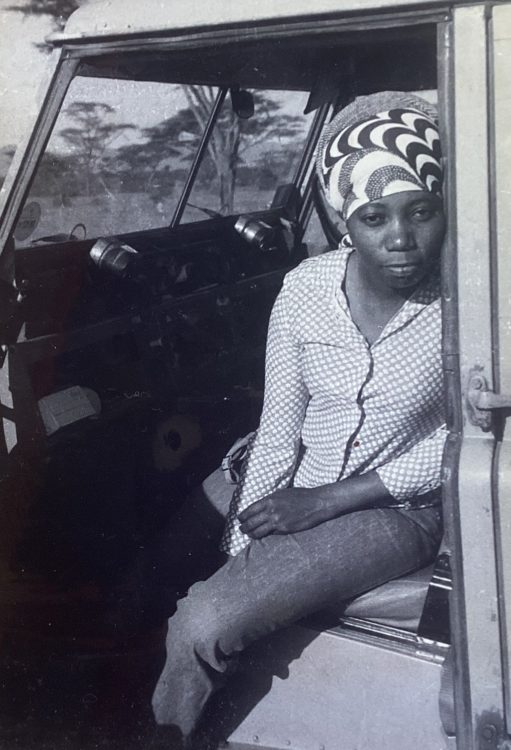

Interview with Joan Semmel, October 13th 2022, New York

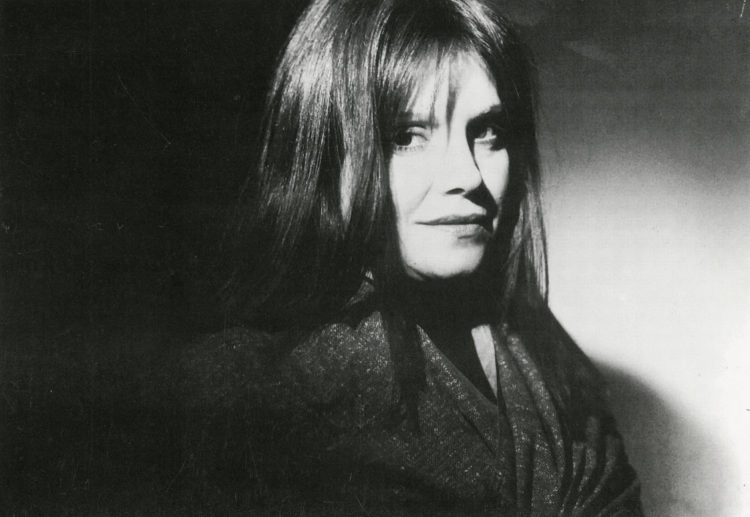

Ewa Giezek is studying a double master’s in History and Art History at Sciences Po Paris and the École du Louvre, respectively. Specialising in 20th-century art, her work focuses on the representation of sexuality in modern art. She is currently working on her dissertation, centred on the eroticisation of the male model. This research was enhanced by a study trip to New York, where Ewa was able to interview artists whose work in the 1970s connected with this subject.