Research

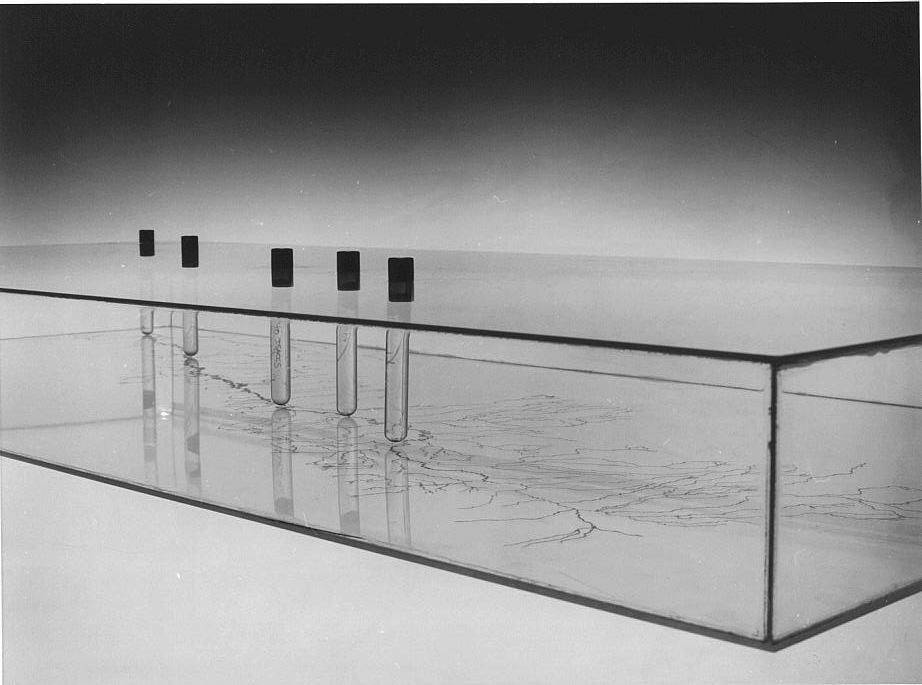

Alicia Barney Caldas, Río Cauca (detail), 1981-1982, showing test tubes containing water samples from various parts of the Río Cauca suspended within, on the bottom of the tank, engraved with photogravure, a map of the river, © Photo: Guillermo Franco

“Have we fallen into a mesmerized state that makes us accept as inevitable that which is inferior or detrimental, as though having lost the will or the vision to demand that which is good?”1

Women have been at the forefront of the modern environmental movement since its beginning, demanding “that which is good”, and they continue to be key leaders in many countries in the fight to protect our world and its resources. Colombia, one of the world’s most biodiverse nations, is no exception, with women such as the environmental activist Francia Márquez asserting their will and vision – in her case by combating the devastation of illegal mining in the department of Cauca, for which she received the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize in 2018. Women artists, too, have participated in the environmental movement by creating critical artworks about ecological issues – eco-art – often at the intersection of feminism and ecology – ecofeminist art—to bring attention to environmental problems and to propose solutions.2 Within histories of eco-art, however, women’s contributions remain under-acknowledged. I wish to bring greater visibility to the efforts of two visionary women who introduced eco-art in Colombia: Alicia Barney (born in 1952) and María Evelia Marmolejo (born in 1958). Their innovative artwork, at the cutting-edge of the art scene in their country in the early 1980s, lost visibility in subsequent decades and is just, in the past few years, beginning to receive much-deserved reconsideration.3

Alicia Barney Caldas, Yumbo, 1980, map and twenty-nine glass cubes, 20 x 20 x 20 cm each, with particulates from the air in Yumbo, Colombia, as collected from 1-29 February 1980, © Photo: Fernell Franco

Alicia Barney Caldas, Yumbo, 2008, recreation of a damaged 1981 artwork, thirty-one glass cubes, 20 x 20 x 20 cm each, with particulates from the air in Yumbo, Colombia, as collected from 1-31 March 2008, © Photo: José Kattan

Early on 1 February 1980 A. Barney went to a site in Yumbo, an industrial city adjacent to her hometown of Cali. There she placed twenty-nine identical, topless glass cubes. She returned early the next day, and again each day that month, to retrieve and cap a cube, each one grimier than the previous as they accumulated particulates circulating in the air. Seen in series, and accompanied by a map of Yumbo showing where she placed them, the cubes make visible the air pollution caused by factories such as the multinational Eternit, known for their trademarked fibre cement that was in increasing demand at a time of rapid industrialisation and urban growth.4 Yumbo is the first of several examples of eco-art that A. Barney made and is the first eco-artwork created or exhibited in Colombia.5

The regular, precise and repeated form of the glass cube lends the artwork itself an industrial look, reminiscent of minimalism. A. Barney’s emphasis on process and context are in accordance with that movement, yet her artwork is post-minimalist, placing emphasis on extra-artistic concerns and thus implicitly critical of minimalism’s formalism. Nevertheless, echoes of minimalism put the artwork in conversation with the white cube of the standard contemporary art gallery while simultaneously evoking and questioning notions of progress tied to industrialism. Yumbo relates, too, to the anatomical display of smokers’ blackened lungs next to those of non-smokers, intended as a deterrent. Such empiricism, standardisation and transparency allow for a complex overlapping of discourses that opens to multiple considerations. These cubes provided an opportunity not just to see a straightforward record of pollution, but to think through the artwork’s connections to various contexts: to the art world, which is so often taken as remote from the real struggles of life; to national political and economic discourse of the previous decade, dominated by ideals of development; to the viewers’ lived experiences, in relationship to their personal health and the risks of long-term exposure to contaminants.

Alicia Barney Caldas, Río Cauca, 1981-1982, three transparent acrylic tanks, 11 x 131 x 60 cm, filled with water from the source of the Río Cauca, with 15 test tubes containing water samples from various parts of the Río Cauca a suspended within, plus photographic documentation and data obtained from the samples. On the bottom of each tank, engraved with photogravure, is a map of the river, © Photo : Mauricio Zumaran

The following year, A. Barney began work on Río Cauca [Cauca River, 1981-1982], documenting the degradation of one of Colombia’s major rivers, which runs through the artist’s natal city and then through Yumbo.6 This artwork displays a decidedly scientific approach, immediately apparent in the artist’s inclusion of test tubes and chemical analyses that attest to the interdisciplinary nature of the project – she collaborated with a scientist to measure the levels of pollutants in the water,7 itself a significant innovation within Colombian art of the period. Three identical transparent acrylic tanks, large and shallow, hold water that A. Barney collected from the river’s source. A map of the river is engraved on the bottom of each tank, and five test tubes are inserted in each tank above the five locations where the artist took water samples. The tanks correspond to samples from the bottom, middle and top of the river in each location. Nearby are the demijohns used to gather the source water, and on the adjacent walls are photographs documenting the water collection along with the chemical analyses. Transparency again is crucial – not just of materials but of process – with exposure as the goal.

With Yumbo, Río Cauca and other eco-artworks of the period, A. Barney hoped that by bringing attention to the problem of contamination and its sources, she could spur the public to act.8 As these artworks reveal, environmental degradation is an outcome of modernisation driven by capitalism, an impact ignored within the official message of progress through industrialisation and technological advancement, fed by the presumably endless bounty of nature. Solutions to such problems must be symbolic as much as practical, since the problems are systemic and widespread and cannot be solved without a drastic change of mindset, on the part of the government, business owners and citizens alike.9

A. Barney’s approach was in line with developments within the environmental movement in Colombia, which between 1972 and 1983 saw an increasing denunciation of ecological degradation on the part of university professors, whereby activist academics tackled problems with scientific rigour rather than mere opinion.10 On the other hand, among the middle class at this time, “an interest in personal experiences and in psychic and physical wellbeing grew, while a new cult of health and a new spirituality, a ‘return to the interior developed”,11 contributing to a greater interest in environmental issues. While A. Barney’s art followed the scientific turn, M. E. Marmolejo’s took a different tack and emphasised personal experience and spirituality.

María Evelia Marmolejo, Anónimo 3, 1982, performance on the banks of the Río Cauca, Prometeo Gallery Ida Pisani Milan, © Photo: Nelson Villegas

María Evelia Marmolejo, Anónimo 3, 1982, performance on the banks of the Río Cauca, Prometeo Gallery Ida Pisani Milan, © Photo: Nelson Villegas

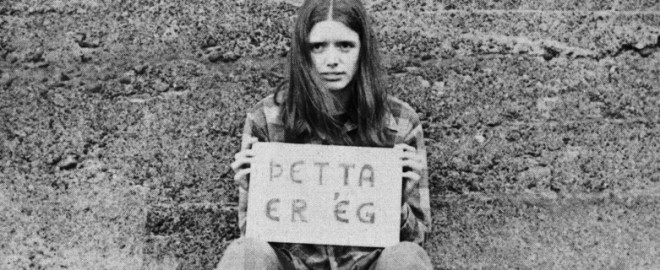

In addition to being one of the first artists to create eco-art in Colombia, in the early 1980s M. E. Marmolejo pioneered performance art that was, moreover, overtly feminist.12 In 1982 she staged Anónimo 3 [Anonymous 3] on the banks of the Cauca River, documenting and exhibiting the performance through video and photography.13 Anónimo 3 was a 15-minute-long ritual, in which the artist, with gauze and medical tape partially covering her naked body and completely obscuring her face, walked around a spiral drawn in quicklime on the ground, arriving at a toilet in the centre of the spiral. There she conducted a vaginal wash, the liquids soaking strips of gauze and tape before falling through the toilet to the ground. She then carefully placed the soaked strips on the ground .14 She described the performance as “an act of atonement”.15 In a text she explained: “Like so many other rivers around the world and – indeed – the earth in general, the Cauca River is suffering the effects of nonbiodegradable waste released into it by industries and human beings. That waste alters nature’s components, upsetting cycles of decomposition and aggravating the destruction of biodiversity, flora and fauna. In response to that damage, I have created a ritual to Mother Earth as a way of asking forgiveness”.16

M. E. Marmolejo’s intense, strange rituals sought to connect to the audience through affect. Descriptions of earlier performances as “signaling physical vulnerability”17 and provoking “catharsis in the spectator”18 apply to this performance as well. Notably, her understanding of the environment and humanity’s place within it departed sharply from those found within Christianity and the Western scientific tradition. Marmolejo felt an affinity for indigenous mythology, particularly as it related to the life-giving power of women’s blood.19 Her art is ecofeminist, although not from an essentialist position that views the natural role of women as that of child-bearer and caregiver. Rather, M. E. Marmolejo sought to reclaim a part of women’s existence – menstruation – that Western culture reviled. The reclamation was above all a symbolic means of changing harmful patterns of social thought and action.20

In two later artworks, M. E. Marmolejo further reflected on ecological destruction, especially its links to violations of the human body. Residuos I and Residuos II [Residues I and Residues II], of 1983 and 1984, were installations whose theme was “the environmental chaos and violence generated by the excessive extraction of oil”.21 In these, containers filled with a variety of biological “waste” – including blood, urine, animal intestines, and even a human foetus, all materials that evoke a strong sense of revulsion – along with other organic materials, referred to the negative impact of petroleum extraction on human bodies.22 Residuos II also included performance. The artist entered the installation naked and facing away from the audience, to emphasise the act of witnessing, with her biographical information written on her back for the public to read. As curator Cecilia Fajardo-Hill has observed, M. E. Marmolejo’s approach to social problems – environmental issues inextricably among them—was “visceral, urgent and compassionate”.23

Although there were certain notable critics and curators who enthusiastically supported the eco-art of A. Barney and M. E. Marmolejo in the early 1980s,24 their work was not generally understood or well-received. They were ahead of their time within Colombia, and their art foreshadowed later projects that employed new media to critically reconsider humans within the environment. Now, environmental degradation is a prominent theme of contemporary art everywhere, and well-known Colombian artists such Miguel Ángel Rojas, Clemencia Echeverri and Carolina Caycedo are celebrated for their contributions. Not only do the precedents for these later developments in Colombian art deserve to be reconsidered, within the current context of climate crisis, the work of Alicia Barney and María Evelia Marmolejo is more relevant than ever.

Carson Rachel, Silent Spring, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 2002, p. 12.

2

The feminist art journal Heresies celebrated this participation in their thirteenth issue in 1981, titled Earthkeeping/Earthshaking, dedicated to feminism and ecology, and more recently, Jade Wildy has examined the history of ecofeminist art in “The Artistic Progressions of Ecofeminism: The Changing Focus of Women in Environmental Art”, International Journal of the Arts in Society 6, No. 1, January 2012, pp. 53-65.

3

Both artists are represented by the Instituto de Visión, a gallery founded in Bogotá in 2014 that includes a focus on “Visionaries”, Colombian artists of the 1980s who, despite their innovations, which paved the way for future developments at a national level, have received little official recognition. Within Colombia, the Instituto de Visión has been crucial in increasing these artists’ visibility. Internationally, the inclusion of A. Barney and M. E. Marmolejo in the recent exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 (curated by Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in 2017) has been important, although that exhibition focused on their works’ relationship to the body and not to ecology.

4

Vásquez Edgar, “Historia del desarrollo económica y urbano en Cali”, Boletín Socioeconómico, No. 20, April 1990, p. 14. I mention Eternit particularly because of its infamy and its CEO’s connection to art: Eternit’s use of asbestos continued well after its danger was recognised, especially in underdeveloped countries with little or no government regulation, and in recent decades Stephan Schmidheiny, Eternit’s former CEO, has been seen as a prime example of the neoliberal use of greenwashing and art-washing (the use of “sustainable economic projects” and art to create a positive image for capitalism). See Villamizar Guillermo, “Daros Latinoamérica: memorias de un legado peligroso”, esferapública, 3 December 2012: http://esferapublica.org/nfblog/daros-latinamerica-memorias-de-un-legado-peligroso/ (accessed 25th March, 2020), and Villamizar Guillermo, “Informe Daros: Arte y dinero”, esferapública, 11 May 2013: http://esferapublica.org/nfblog/informe-daros-arte-y-dinero/ (accessed 25th March, 2020) A. Barney drew my attention to these articles.

5

It was included as part of the travelling group exhibition Arte para los años 80, which opened at the Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia in Cali, Colombia on 21 March 1980.

6

A. Barney presented an early version of the artwork as part of the I Coloquio de Arte No-objetual y Arte Urbano held in Medellín in May 1981. The completed artwork debuted in the exhibition Actitudes Plurales at the Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia, Cali in November 1982. González Miguel, “Alicia Barney: El Paisaje Alternativo”, Arte en Colombia, No. 19, October 1982, p. 42.

7

A. Barney worked with biologist Roberto Díaz, professor at the Universidad Nacional in Palmira. See the page “Obra” in artist’s website: https://www.aliciabarneycaldas.com/obra, accessed 25th March, 2020.

8

Barney A., untitled and unpublished text, 2017.

9

Nancy Motta González and Aceneth Perafán Cabrera make this argument in their book Historia ambiental del Valle de Cauca: Geoespacialidad, cultura, y género, Cali, Universidad de Valle, 2010, pp. 21-24. N. González, an anthropologist, and A. Perafán, a sociologist, identify “the lack of control by the authorities, in addition to the indifference of citizens and businesses in the face of the effects of degradation … of the Cauca” as the greatest problems, p. 79. Translation by the author.

10

Tobasura Acuña Isaías, “El movimiento ambiental colombiano: Una aproximación a su historia reciente”, Ecología Política, No. 26, 2003, p. 111.

11

Ibid.: “Se aumentó el interés por las experiencias personales, el bienestar psíquico y físico, a la vez que se desarrollaba un nuevo culto a la salud y una nueva espiritualidad, una ‘vuelta a la interioridad’.” Translation by the author.

12

Fajardo-Hill Cecilia, “María Evelia Marmolejo’s Political Body”, ArtNexus 85, June-August 2012, https://www.artnexus.com/en/magazines/article-magazine/5d64034190cc21cf7c0a342e/85/maria-evelia-marmolejo-s-political-body, accessed 25th March, 2020.

13

She exhibited Anónimo 3 at the 8th Salón Atenas, Museo de Arte Moderno in Bogotá in November 1982.

14

Fajardo-Hill Cecilia, “María Evelia Marmolejo’s Political Body”, op. cit.

15

Quoted in Jaramillo Carmen María, “In the First Person: Poetics of Subjectivity in the Work of Colombian Women Artists, 1960–1980”, in Radical Women Artists: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, eds Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta, exh. cat., Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2017, Brooklyn Museum, New York, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2017-2018, Munich, New York, DelMonico Books, Prestel, 2017, p. 263.

16

Ibid. and Fajardo-Hill Cecilia, “María Evelia Marmolejo’s Political Body”, op. cit. She also quotes a part of this statement, and she clarifies that M. E. Marmolejo wrote it in 1982 but then revised it in 2010-2011.

17

Serrano Eduardo, “Rosemberg Sandoval and María Evelia Marmolejo ‘Actos y situaciones’”, Re-Vista del Arte y la Arquitectura en América Latina 2, no. 8 (1982): p. 55. E. Serrano was describing the performance 11 de marzo 1982, held at the Galería San Diego in Bogotá on that date.

18

González Miguel, “Cali”, Re-Vista del Arte y la Arquitectura en América Latina 2, No. 8, 1982, p. 55. M. González was describing M. E. Marmolejo’s first performance, Anónimo 1, which took place in the Plazoleta del Centro Administrativo Municipal in Cali in 1981.

19

As M. E. Marmolejo explained, in Catholic school she was taught to be ashamed of menstruation. She stated, “When I learned about the indigenous myth which positions menstruation as the primary element to create man, the taboo which had been imposed by religion collapsed. It was then that I saw clearly that menstruating was something worthy of praise”. Correspondence with the author, 11 April 2019.

20

Fajardo-Hill Cecilia, “María Evelia Marmolejo’s Political Body”. She notes that M. E. Marmolejo’s work was mistakenly dismissed as essentialist and argues that it is not.

21

Marmolejo M. E., correspondence with the author, 11 April, 2019. Residuos I (1983) was installed at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Cartegena. She created and performed Residuos II (1984), for the 24th Salón Nacional de Artes Visuales, in the city of Pasto.

22

Fajardo-Hill Cecilia, “María Evelia Marmolejo’s Political Body”. She reports that the foetus referred to infant mortality, in response to an article the artist read.

23

Fajardo-Hill Cecilia, “María Evelia Marmolejo’s Political Body”.

24

Both Eduardo Serrano, curator of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá, and Miguel González, a prominent critic and curator in Cali, enthusiastically promoted the art of A. Barney and M. E. Marmolejo in the early 1980s.

Dr Gina McDaniel Tarver is associate professor of art history at Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. She received her PhD from The University of Texas at Austin, where she was a Fulbright grant recipient. She specialises in the modern and contemporary art of Latin America with particular interest in gender, spatial and ecological politics. Her research has focused on the work of several women artists, particularly Feliza Bursztyn, Beatriz González and Alicia Barney, who have challenged gender norms and helped to shape Colombian art. She is the author of The New Iconoclasts: From Art of a New Reality to Conceptual Art in Colombia, 1961–1975 (Ediciones Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, 2016), and co-editor, with Michele Greet, of Art Museums of Latin America: Structuring Representation (Routledge, New York, 2018).

Gina McDaniel Tarver, "“The vision to demand that which is good” : Alicia Barney, María Evelia Marmolejo and the origins of Colombian eco-art." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/la-penetration-necessaire-pour-exiger-le-bon-alicia-barney-maria-evelia-marmolejo-et-les-origines-de-lart-ecologique-colombien/. Accessed 8 July 2025