Research

Amal Abdenour, Maman ne pleure pas ! je suis bien ! [Mum, Don’t Cry! I Am Fine!], 1974–1979, electrography, 41 x 93 cm, © photo : Gregory Copitet © Courtesy Enseigne des Oudin

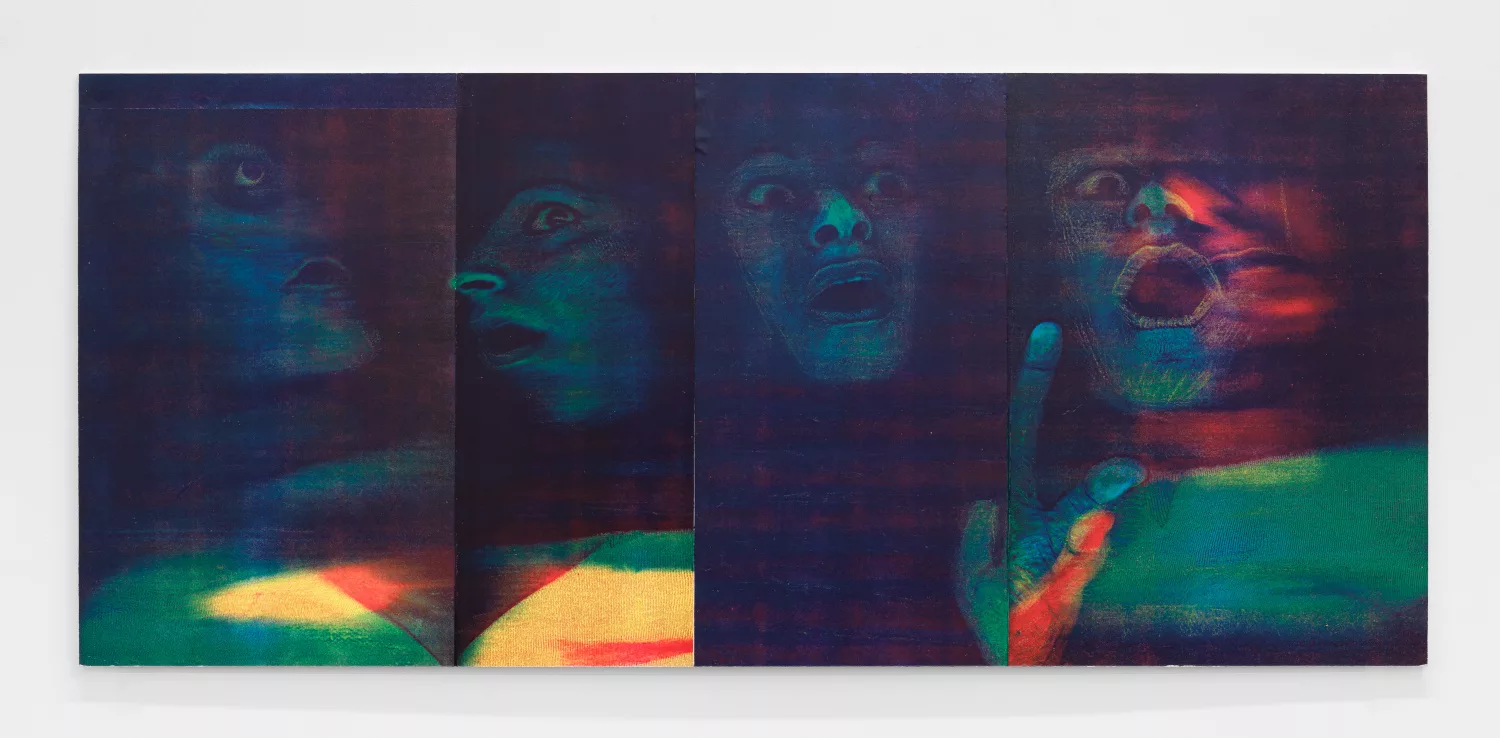

In the aftermath of the events of May 1968 in Paris, the story of the artistic paths of Arab women artists in Paris turned a page. These artists would be characterised by their quests for a political emancipation, and a poetic one, generating strategies through which to reappropriate and reclaim the female body in the face of various systems of oppression, war and censorship. Through an anthropocentric feminism, in which the body of the artist and the body of work is one, the artists sought to move beyond the use of traditional mediums in favour of experimentation.

Nil Yalter, Topak Ev [Round House], 1973, installation, metal structure, felt, sheepskins, painting, leather, text, mixed media, exhibition view, Nil Yalter, 1973-2015, Verrière-Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, Bruxelles, 2015, Courtesy Nil Yalter & Verrière-Fondation d’entreprise Hermès © Photo: Isabelle Arthuis © ADAGP, Paris

Nil Yalter, The Headless Woman or The Belly Dance, video-performance, 24 min © Courtesy Nil Yalter © ADAGP, Paris

Nil Yalter, The Headless Woman or The Belly Dance, video-performance, 24 min © Courtesy Nil Yalter © ADAGP, Paris

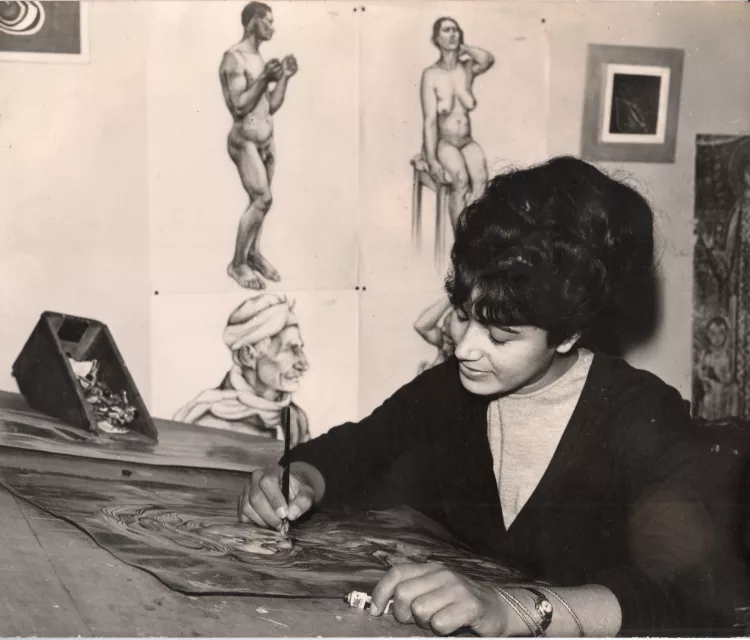

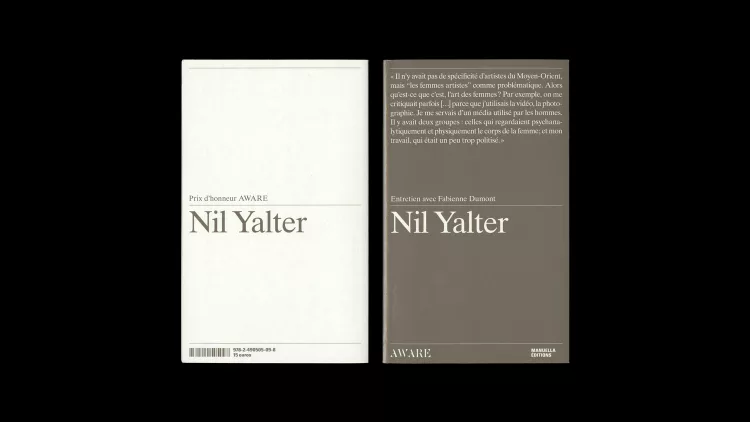

Nil Yalter was born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1938 and moved to Paris in 1965. There she would develop an artistic practice that focused on studying the living conditions of migrant communities, expressed in graphics, drawings and photographic montages, making her a pioneer of post-ethnographic art.1 Discovered by Suzanne Pagé, director of the Animation –Recherche – Confrontation (ARC) project at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, in 1973 she was invited to create her first solo exhibition at the museum, entitled Topak Ev [Round House]. This emblematic installation took the form of a yurt, or a house for women, inspired by the tents of the nomadic Bektik communities of Central Anatolia. Over the following decade, N. Yalter would participate in six ARC exhibitions at the Musée d’Art Moderne.2 In 1974, in the first group exhibition dedicated to video, Art Vidéo / Confrontation 74, she presented The Headless Woman or The Belly Dance (24 min), a feminist video-performance in which she performs the titular dance. Drawn around her navel are Quran verses that, in Anatolia, are inscribed by Muslim priests on the stomachs of women deemed sterile or rebellious: rewritten in this way by the artist they are subverted. To the sound of feverish music, a fixed close-up of the artist’s stomach – corporeally engaged in the performance – gives us the impression of reading from a surface in motion.3 It is a kind of tattoo intended to exorcise the violence against ‘sterile’ women and to denounce sexual violence on a wider scale, as well as religious or political systems that look to seize control of women’s bodies. It is an alarming work, and remains so as we look to Trump’s United States and its introduction of abortion bans and attacks on women’s bodily autonomy. In its ultra-focus on the site of the stomach, N. Yalter renders the viewer a voyeur, allowing her to better deconstruct the Orientalist trope of belly dancing – one of the most prevalent vectors of the oppression of the body of the ‘Arab woman’ in a system of colonial representations. The Headless Woman thus decapitates (or reframes) the fetishised image of woman, replacing it with the notion of the body as a site of conflict and a place of exorcism.

Amal Abdenour, 9 Unités triomphantes [9 Triumphant Units], 1970-1979, electrography – black and white photocopier – 9 units, joined together in one work (right panel), 40 x 218 cm, photo: Gregory Copitet © Courtesy Enseigne des Oudin

Amal Abdenour, 9 Unités triomphantes [9 Triumphant Units], 1970-1979, electrography – black and white photocopier – 9 units, joined together in one work (left panel), 40 x 218 cm, photo: Gregory Copitet © Courtesy Enseigne des Oudin

Amal Abdenour, Maman ne pleure pas ! je suis bien ! [Mum, Don’t Cry! I Am Fine!], 1974–1979, electrography, 41 x 93 cm, © photo : Gregory Copitet © Courtesy Enseigne des Oudin

Amal Abdenour (1931–2020) was born in Nablus, Palestine. She studied in Egypt before enrolling at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1962, where she took up fresco painting. Her relationship to Paris was specifically forged through explorations in body art and electronic arts, and notably through her innovations in the avant-garde field of copy art in the 1970s. Somewhere between the computer and the postcard, other proponents of copy art included Nicole Métayer, Laurie Karp and Claude Torey. A. Abdenour’s ‘anthropomorphic electrographs’,4 created by superposing and arranging Xerox photocopies, were conceptual self-portraits that captured parts of the artist’s body in unlikely positions, frozen by the photocopying mechanism. Soon recognised by numerous contemporary art journals, the works depict a body exploded into handprints, footprints and genitalia. The artist created series of autosexual prints, a provocative gesture and a generative one. It is another example of an unframing of the fetichised image of a woman into something more ambiguous, shapeshifting, hybrid, evoking scientific imagery – at once anti-erotic and anti-aesthetic. In these series we may observe a feminist reappropriation of the woman-print of Yves Klein’s anthropometries and their problematic use of woman as paintbrush. The genitalia prints, captured from life and reconstructed or spliced together using vision-troubling contrasts of black/white/grey, are ultimately a site of self-affirmation and a will to power. The photocopier itself becomes a tool of de-alienation, a feminist device. Just like N. Yalter’s headless woman, the woman-vulva of A. Abdenour functions as phenomenal subjectification: throwing her own body into her work in a decisive gesture, the artist neutralises her own subjectivity at the service of a subjectile body or a body-pulsation, that of music or of the photocopier.5 To this ritual or mechanical process the artist brings the power of performativity, preventing the female body from being seen in its totality, its integrity, its objectivity: an unframed body. In 1986, concluding a cycle of works that had spanned almost two decades, A. Abdenour presented the retrospective L’artiste et la machine at the UNESCO Palace in Paris.

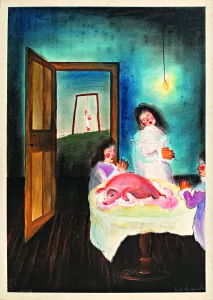

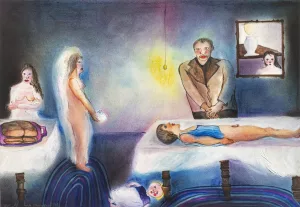

Laila Muraywid, Crucifixion, 1979, gouache, ink and pastel on paper, 48 x 34 cm © Courtesy the artist

Laila Muraywid, Le Sacrifice [The Sacrifice], 1979, gouache, ink and pastel on paper, 48 x 34 cm © Courtesy the artist

Laila Muraywid, Adam et Eve chassés du paradis [Adam and Eve expelled from paradise], 1979, gouache, ink and pastel on paper, 34 x 48 cm © Courtesy the artist

Laila Muraywid, Trois femmes et une histoire [Three women and One Story], 1979, gouache, ink and pastel on paper, 36 x 48 cm © Courtesy the artist

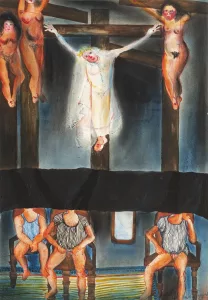

Laila Muraywid was born in Damascus in Syria in 1956, and during her exile in Paris discovered, like N. Yalter and A. Abdenour, an opportunity to experiment between mediums and genres.6 In 1981 she won a scholarship and enrolled at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, where alongside her engraving and drawing practices she would become interested in photography. In a series of rarely-exhibited medium-format gouaches, the artist marked her farewell to Syria and her move to Paris, and these works merit discussion. They are more narrative and less performative than works by N. Yalter and A. Abdenour, but no less radical in their subversion of the established order surrounding the condition of women in the Arab worlds, where women participate in all revolutions and struggles for reform and social advances, but rarely reap the benefits in the form of civil rights. The works date from 1979, and are composed like icons or miniatures depicting scenes of daily life, seemingly familiar and intimate interiors that appear normal at first glance but whose staging contains something macabre. Amongst these visions of ritual sacrifices involving humans and pigs, sexual dreams or nightmares and hangings, a troubled, disturbing atmosphere arises that recalls Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). The works, whose titles include Sacrifice and Crucifixion, number around twenty, and make use of mise en abyme – their images are doubled through windows, doors and doorways – or are bisected into two scenes, with characters sometimes repeated but now decapitated. Fragmented and mutilated bodies seem to offer themselves to hell or the apocalypse, splayed on the kitchen table or in the living room as in a torture chamber. No doubt remains as to whether this violence, in its profanity of the codes of religious and patriarchal law, is an accurate reflection of the brutality of the Syrian regime of Hafez el-Assad, under which the slightest opposition was brutally supressed, and life as a woman and as an artist represented a daily double struggle. At the time, exile in Paris also symbolised an exit door, a breath of fresh air.

Our final example of the unframed body as radical feminist strategy is the case of Mona Hatoum, born in 1952 in Beirut in Lebanon (with Palestinian origins) and her first video work, The Negotiating Table (1983, 20 min).7 The performance is considered the artist’s most overtly political, an explicit response to the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982. In a darkened room, M. Hatoum lies motionless on a table for several hours, entirely enclosed in a plastic bag that is covered with blood and entrails, as if the inside of the body that lies within had been revealed to us. The work is a sacrificial table, recalling the sacrificial tables of L. Muraywid’s drawings. Its second dimension is a radio broadcast that relays reportages covering the Lebanese Civil War, the Israeli invasion, peace ‘negotiations’ between leaders etc. A tracking shot: frontal, insistent and automatic, brings us ever closer to the prone body as the news gets louder and louder. And so it is only gradually that we begin to realise the obscene or abject aspect of the body laid out on the table. It is a vision delayed. Paradoxically, the closer we get, the more the unformed takes on a form. But the body itself seems to elude us, and a violence as muffled and unfathomable as that of L. Muraywid’s gouaches takes its place. Here we find the same effect of subjectification as was present in the work of N. Yalter and A. Abdenour: the artist performs her entry into her own work, or, put differently, the body of the artist becomes the body of the work by mediation through video or photocopier. Though M. Hatoum’s relationship to Paris may be less significant than that of the three artists cited earlier, the Lebanese artist nevertheless made Paris her home during the 1990s, during which time she taught at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts. And there is no doubt that The Negotiating Table was one of a number of pioneering works that contributed to M. Hatoum’s international renown, in its melding of experimental video, performance and radical feminism. In an echo of the works evoked above, we discover a unity: their ultimate effect is an unframing of the myth, too long cultivated by art history, of the ‘woman-object’, via the headless woman, the woman-belly, woman-vulva and now the woman-martyr.8

The term ‘post-ethnographic’ can be used to unite an ensemble of practices developed from the beginning of the 1990s, which involved revisiting, elaborating on or repositioning the inherited questions and gestures of the field of ethnography; these practices developed alongside an internal questioning of the discipline of anthropology and its colonial origins. See Foster, Hal, “The Artist as Ethnographer”, in The Return of the Real, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1996, p. 171-204.

2

See the essay by Burluraux, Odile, “Présences arabes dans les musées parisiens: intégration et/ou subversion” in Présences arabes. Art moderne et décolonisation. Paris 1908-1988, exh. cat., Paris, Musée d’Art moderne de Paris, Paris-Musées, 2024, p. 16-20.

3

N. Yalter selected the words and phrases from writings by the anthropologist René Nelli.

4

Expression used by Violaine Sautter in a poetic text devoted to the works of A. Abdenour, “Électrographies anthropomorphiques d’Amal Abdenour”, in Albatroz. Literatura de Aguarras, no. 19, April 1993, p. 174.

5

A. Abdenour and N. Yalter were working in Paris at the same time in the 1970s, but their paths did not cross.

6

This openness to multimedia art and other experimental practices often came about more as a result of the burgeoning international scene in Paris than from the avant-gardism as taught in schools, beginning with the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, where academic forms and practices tended to persist.

7

The Negotiating Table was created as part of a series of performances conceived when the artist was resident at Western Front, Vancouver (Canada).

8

The artists and works discussed in this essay were brought together in the same space for the exhibition Présences arabes. Art moderne et décolonisation. Paris 1908-1988, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (5 April–25 August 2024). As such, this essay serves as a theoretical continuation of a curatorial experience.

Morad Montazami is an art historian, publisher and exhibition curator. After a period working at London’s Tate Modern (United Kingdom) between 2014 and 2019, he developed the editorial and curatorial platform Zamân Books & Curating, which explores and revalorises Arab, African and Asian modernities. He recently co-curated the exhibitions Casablanca Art School, Tate St-Ives-Sharjah Art Foundation-Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2023–2024 and Présences Arabes. Art moderne et décolonisation. Paris 1908-1988, Musée d’art moderne de Paris, 2024.

An article produced in partnership with the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris and Zamân Books & Curating within the scope of the programme Role Models

Morad Montazami, "The body unframed. Radical feminist strategies of artists from the Arab world in exile in Paris in the years 1970-1980." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/le-corps-de-cadree-strategies-feministes-radicales-chez-les-artistes-des-mondes-arabes-en-exil-a-paris-annees-1970-1980/. Accessed 5 March 2026