Research

Alicia D’Amico, Primera Asamblea Feminista, Mar del Plata, abril de 1990, [First feminist assembly, Mar del Plata, April, 1990], 1990, 35 mm silver print © Archivo Alicia D’Amico

“There is a living history dwelling within each and every one of us, comprised of memories, affects, subconscious signs; I do not believe that historical value only applies to that which is exterior to us and has been validated by others, what is notoriously called objective history. I narrate a non-exclusive living history, an imagination rooted in personal experience, a history that is truer because it does not erase love’s reasons nor expel relationships from its cognitive process.”1

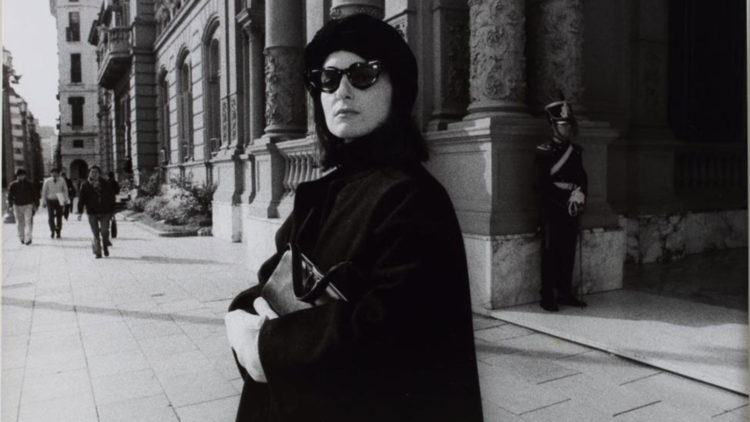

Alicia D’Amico, 8 de marzo de 1984 [March 8, 1984], 1984, 35 mm silver print © Archivo Alicia D’Amico

This article seeks to demonstrate the links between the political concept of lived experience as it arose in the radical feminist movements of the 1970s and the investigative methodology put forward from the standpoint of feminist ideology in the contemporary arts. The affective links established between us and the artists we work with offer us other ways of seeing their work, free of the Kantian distancing that has marked art history and criticism. This leads to a richer and more complex relationship between art historians and feminist artists. It is vital that feminist currents recognise the political importance of these links, a recognition clearly expressed in an investigative practice fully engaged with other ways of seeing art and artists.

The first consciousness-raising groups emerged within the feminist movement in the 1960s as part of the overall digging up of the roots of female submission and discrimination. Setting out to deconstruct the oppression of women, they constructed theory based on women’s personal, lived experiences, arguing that “the personal is political”. Kathie Sarachild gave a name to these practices of collective self-analysis in her account of the meetings held by the New York Radical Women group in 1967. She quotes the comments made by a woman named Ann Forer in one of these sessions, and concludes, “I realized I could still learn a lot about how to understand and describe the particular oppression of women in ways that could reach other women in the way this had just reached me. The whole group was moved as I was, and we decided on the spot that what we needed – in the words Ann used – was to ‘raise our consciousness some more’.”2

The aim of this methodological practice is to achieve a political understanding of women’s daily lives, redefining the term “political”. But it is also an expression of an ideological position about traditional science. In this regard, Sarachild explains, “The decision to emphasize our own feelings and experiences as women and to test all generalizations and the reading we did by our own experience was actually the scientific method of research. We were in effect repeating the 17th-century challenge of science to scholasticism, ‘study nature, not books’, and put all theories to the test of living practice and action.”3

In this way, feminists criticised the omniscient “eye” of contemporary science that claims to see everything unhindered by any standpoint, thus covering over the issue of the subjects of that knowledge, who were largely male, white, heterosexual and socially better off. This dismantling of the historically legitimated system of knowledge – which has impacted all the disciplines that feminists have revisited since the 1960s – posits an embodied subject situated in a concrete social structure, a gendered and racialised subject. As Donna Haraway argues, “We need to learn in our bodies, endowed with primate color and stereoscopic vision, how to attach the objective to our theoretical and political scanners in order to name where we are and are not, in dimensions of mental and physical space we hardly know how to name. So, not so perversely, objectivity turns out to be about particular and specific embodiment, and definitely not about the false vision promising transcendence of all limits and responsibility. The moral is simple: only partial perspective promises objective vision.”4

In short, collective practices of women recounting their own experiences are forms of knowledge transmission. Sarachild continues, “Consciousness-raising was seen as both a method for arriving at the truth and a means for action and organizing. It was a means for the organizers themselves to make an analysis of the situation, and also a means to be used by the people they were organizing and who were in turn organizing more people. Similarly, it wasn’t seen as merely a stage in feminist development which would then lead to another phase, an action phase, but as an essential part of the overall feminist strategy.”5

Alicia D’Amico, Performance de Liliana Mizrahi [Performance by Liliana Mizrahi], 1983, 35 mm silver print © Archivo Al¡cia D’Amico

In the 1970s the Italian feminist art historian Carla Lonzi analysed the existence of a false consciousness based on the instrumental, hierarchical and asymmetric power relations that constitute patriarchy. Similarly, the culture that arises within this matrix naturalises the instrumentalisation and subordination of all that is female. She argues that art is a form of cultural subjugation. Therefore, she concludes, to escape from the false consciousness in which patriarchy situates females, women must speak out through consciousness-raising.6 We should recognise, however, that such speech acts can acquire an aesthetic dimension through both exposure and empowerment, making art a very important tool to bring about real change in people’s daily lives. In this respect, Amelia Jones writes, “In the art world, consciousness raising was seen as parallel to art making, which itself took on a therapeutic cast and came to be seen as a direct, creative ‘outlet’ for women to express their own experience as female subjects in patriarchal culture […].”7

Regarding the use of this methodology to produce scholarly work on living artists, clearly the political value of lived experience enters by way of consciousness-raising, which acquires its full meaning in the contextualisation and interpretation of their artworks. At the same time, we cannot neglect the emotional connection that develops between the art historian and the artist, given that Kantian distancing, a pillar of the so-called objective interpretation of art, is made to shrink as empathetic links are forged. As for those art historians whose field of study involves dead women artists, work with the artist’s correspondence or interviews with their friends and family can yield important information about their lived experiences during the various stages of their life to which their artworks are testament.

I believe in the fundamental importance of demystifying the process of art historiography and so must emphasise that Kantian distancing, claims of objective interpretation and the myth of the artist as genius all work to produce a mysticism that clouds research methods. Therefore, the category of lived experience, a concept at the core of a feminist pedagogy, is, as Diana Fuss points out, “never as unified, as knowledgeable, as universal, and as stable as we presume it to be”.8 On the contrary, it is infused with ideology, and, as Louis Althusser tells us, “When we speak of ideology, we should know that ideology slides into all human activity, that it is identical to the ‘lived’ experience of human existence itself: that is why the form in which we are ‘made to see’ ideology in great novels has as its content the ‘lived’ experience of individuals. This ‘lived’ experience is not data, the data given by ‘pure’ reality,’ but the spontaneous lived experience of ideology in its particular relationship to the real.”9 In this sense, the category of lived experience, because it is infused with the experience of ideology, and because of the instability of reality, allows us to understand artworks as consequences of a complex existence grounded in both structural patriarchy and the spaces of freedom in the life of a woman artist. I understand this methodology as feminist political work that both transforms the lives of women art historians and the discourses that constitute this discipline. If we should see speaking out as a transformative political action, as Lonzi says, there is no reason to confine this transformation to the discursive practice of art history. Consciousness-raising can also be conceived as operating simultaneously on both sides, transforming both women artists and women art historians.

Alicia D’Amico, ll Encuentro Feminista Latinoamericano y del Caribe, Lima [Second Latinoamerican and Caribean feminist gathering, Lima], 1983, 35 mm silver print © Archivo Alicia D’Amico

I would like to conclude by referring to a personal experience, my research regarding the Argentinian photographer Alicia D’Amico (1933-2001). I started cataloguing and digitising her work in 2015, and over the years my reading of her letters and other writings have allowed me to establish an emotional dialogue with her surviving friends and lovers, as well as family members who supported the archive project. A feminist methodology makes it possible for me to connect with D’Amico’s own emotional ties with her nephews, producing an understanding of some of her photos that could not have been obtained without the existence of this mediation between art and affect. The ability to understand how, as a feminist, D’Amico constructed affective relations which were constitutive components of her artworks, opens pathways to richly human interpretations. While this methodology necessitates a longer period of gestation precisely because it requires developing a relationship of mutual confidence with the artist’s loved ones, it has brought me great gifts in terms of my own personal development and professional ability to recount a “living history” that “does not erase love’s reasons nor expel relationships from its cognitive process”.10

Marirì Martinengo, “La voz del silencio. Me llama desde siempre”, Duoda: Revista d’estudis feministes, no. 40 (2011): p. 44.

2

Kathie Sarachild, “Consciousness-Raising: A Radical Weapon”, in Feminist Revolution, ed. Redstockings of the Women’s Liberation Movement (New York: Random House, 1978), p. 144.

3

Ibid, p. 146.

4

Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective”, Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Fall 1988): pp. 582-583.

5

Sarachild, “Consciousness-Raising”, p. 147.

6

Carla Lonzi, Let’s Spit on Hegel: The Clitoral Woman and the Vaginal Woman and Other Writings (Milan: Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, 1986).

7

Amelia Jones, “Feminist heresies: “Cunt Art” and the Female Body in Representation”, Herejías. Critica de los mecanismos = Heresies. A Critic of Mecanisms, exh. cat., Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, Palma de Gran Canaria, (June 6–July 23, 1995), (Palma de Gran Canaria: Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, 1995), p. 625.

8

Diana Fuss, Essentially Speaking: Feminism, Nature and Difference (New York: Routledge, 1989), p. 114

9

Louis Althusser, “Letter on Art in Reply to André Daspre,” On Ideology (London: Verso Books, 2020).

10

Martinengo, “La voz del silencio. Me llama desde siempre”.

María Laura Rosa holds a PhD in contemporary art (UNED, Madrid). She is a researcher at Argentina’s CONICET (National Scientific and Technical Research Council) and a professor of aesthetics in the art department at the University of Buenos Aires. She has edited De cuerpo entero. Debates feministas y campo cultural en Argentina 1960-1980 (2021) and Compartir el mundo. La experiencia de las mujeres y el arte (2017) and is the author of Legados de libertad. El arte feminista en la efervescencia democrática (2014). With Julia Antivilo she curated the exhibition Polvo de Gallina Negra. Mal de ojo y otras recetas feministas, presented at CENAC in Chile and Amparo in Puebla, Mexico in 2022.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

María Laura Rosa, "Experience as an Affective Methodology of Investigation." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/lexperience-comme-methode-de-recherche-affective/. Accessed 4 July 2025