Research

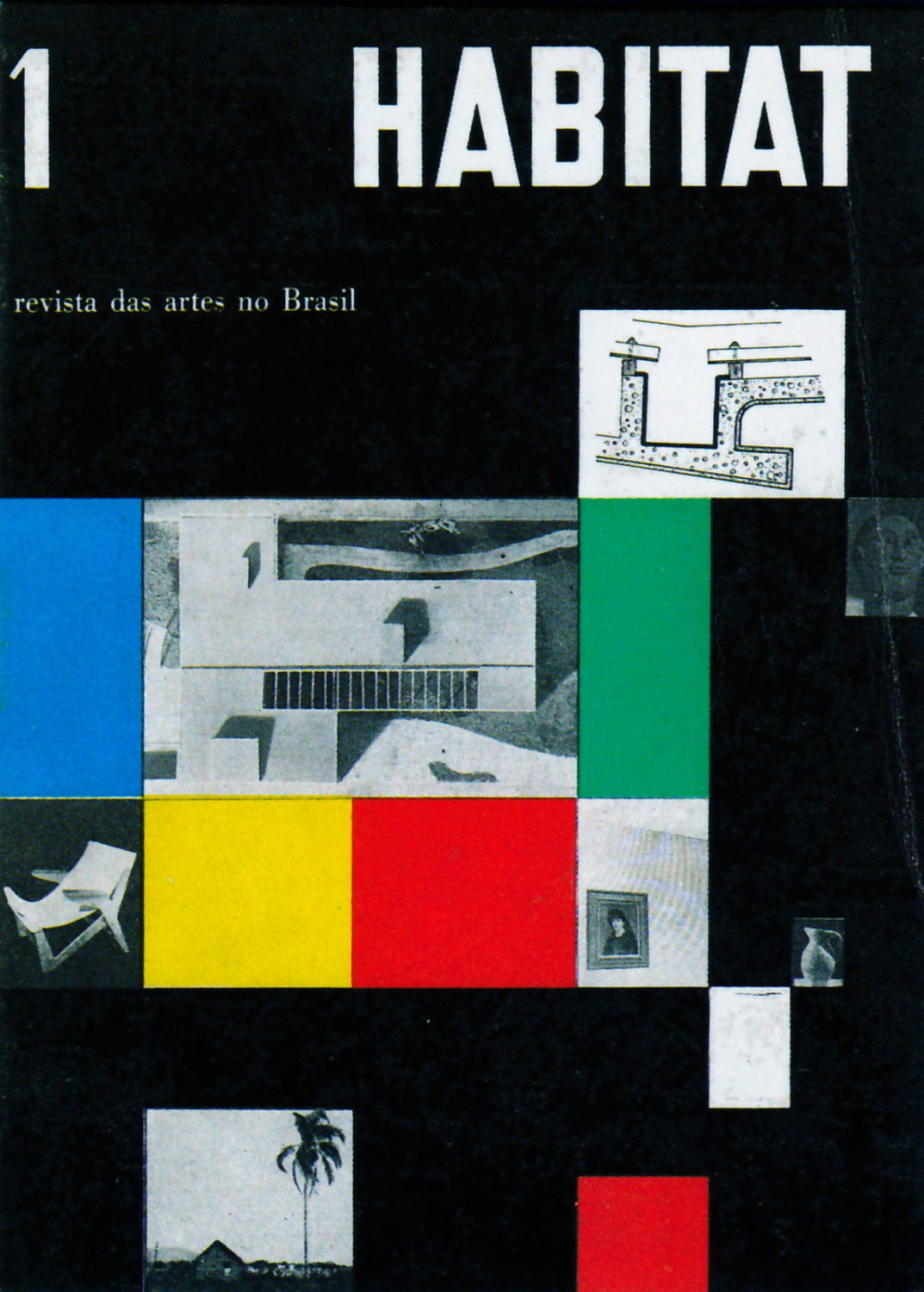

Cover of Habitat, n°1, Oct-Dec 1950 (designed by Lina Bo Bardi). Photo courtesy Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi.

In 1950, Habitat, a “review of architecture and art in Brazil”, was the tool of an ambitious hands-on cultural project run by the architect Lina Bo (1914-1992) and Pietro Maria Bardi, her husband and the magazine’s joint founder.

Lina Bo Bardi in Brazil in 1948, during Carnival, with a necklace designed by herself. Photo courtesy Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi.

Involving all the various disciplines around architecture—from art to design, from dance to fashion, and from photography to craftsmanship—Habitat’s goal was to define a modern environment, in the broadest sense of the term, as “dignity, morality of life and, consequently, spirituality and culture”, as was set forth in its first editorial1. Like a perfect echo of the social and cultural changes then under way in São Paulo from the 1940s on, when that booming industrial metropolis was turned into the country’s economic and cultural capital, the goals of that multidisciplinary magazine also incarnated the thoroughly European enthusiasm of its founders: a pair of Italian intellectuals who had survived the war and were new arrivals in Brazil, a young country and one “condemned to be modern”, to use Mario Pedrosa’s apt words.2 Once there they tried to apply avant-garde ideas that had matured in Europe before the war, using tools which respectively suited them best. Pietro Maria Bardi, a critic and gallery owner,3 thus became the director of the Art Museum in São Paulo (MASP), while for Lina Bo Bardi, who has already worked as an illustrator for the magazine Lo Stile (run by Gio Ponti), and had been the editor of Domus and Quaderni di Domus, an architectural magazine fitted the bill to perfection. Although founded together with her husband, and closely bound up with the cultural politics of the MASP, Habitat was thus eminently indebted to Lina Bo Bardi’s way of thinking, and her intellectual approach, and she actively took charge of the publication’s management for the first fifteen issues, from October 1950 to December 1953.4

In a publishing context where the only two architectural periodicals (Arquitetura e engenhariaand Acrópole) had a predominantly technical character, and when there was still no real art magazine, in the literal sense of the term, in the country, Habitat can be acknowledged as the pioneer of a model destined to come to the fore in the Brazilian scene until the 1960s. Focused on architecture, open to every kind of discipline, and aimed at constructing a modern aesthetic with a national spirit, that model would be borrowed and continued by Arquitetura e decoração, Brasil Arquitetura Contemporânea and Módulo, which all came into being during the 1950s.

Cover of A Cultura della vita, no 9, June 1946. DR.

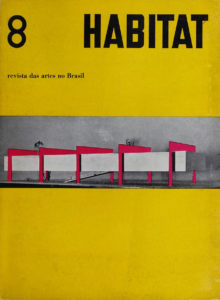

Cover of Habitat, no 8, with the project by Lina Bo Bardi for the Museo de Arte de Sao Paulo. Photo courtesy Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi.

Modern Inhabitation

Dwelling, or the art of “modern inhabitation”, had been a theme dear to Lina Bo since the years when she worked in Italy with Grazia, Lo Stile and A Cultura della vita. This theme turned out to be especially urgent in a country undergoing tremendous population growth like Brazil, where great social disparities were evident, in the eye of the young immigrant, in the architectural contrast between the large modernistas skyscrapers, already famous all over the world,5 and the lowly abodes built on piles, housing the most destitute social classes. For Lina Bo Bardi, the observation of this deep social gap heightened the urgent need to intervene, through art and architecture, in order to improve living conditions for the poorest Brazilians and, at the same time, become engaged in the social education of the new middle class, rightly perceived as the real protagonist in the rapid economic and cultural development occurring in the country’s large cities.

Greatly helped by her Italian experience with periodicals, among other publications, aimed at a broad readership (titles such as Vetrina e negozio and Bellezza), her aim, with Habitat, was to address both the working classes—in order to stir them into action and liberate them through art—and the middle classes—in order to transform their elitist notion of culture. In a large format6 with a neat and careful finish, a wide range of paper qualities and a particular attentiveness to its graphic appearance, Habitat did not hide its goal of involving different social contributors in a democratic project to do with culture and society that was at once accessible and extremely ambitious. It would be simplistic, in the early 1950s, to define Habitat as a mere architectural review,7 but this factor nevertheless remained the catalyst for her cultural programme. Endowed with a “socially artistic function”,8 architecture, in the special meaning which Lina Bo Bardi gave the word, was a means of transforming the day-to-day life of cities, and the attitudes and mentalities of their inhabitants.

Couverture de Habitat, no 1, oct-déc 1950 (dessinée par Lina Bo Bardi). Photo courtesy Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi.

« Amazonas. O povo arquiteto » (« Amazonie. Le peuple architecte »), dans Habitat , no 1, oct.-déc. 1950. Photo courtesy Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi.

A Laboratory of Concepts

Several works produced by Lina Bo Bardi were presented in the magazine’s first issues, ranging in variety from architectural projects9 and furniture10 to jewellery.11 On the other hand she only wrote a few articles for Habitat.12 It was rather in its overall design and layout that Habitat represented a laboratory for its editor’s theoretical principles, and her intellectual, social and political commitment. In the discussions that she decided to play host to, in the projects that she was keen to compare, and in the novel association between different disciplines and artistic periods that were poles apart, all the major themes of Lina Bo Bardi’s thinking were announced: her conviction about the educative power of culture,13 her refusal of dogmatic classifications and all manner of formalism,14 her inclination to engage in discussion, not to say controversy,15 her avant-garde conception of the museum,16 and even her definition of the “historical present”, which would be her motto until the 1990s.17

The early years of Habitat also overlapped with the discovery, for Lina Bo Bardi, of activities at a popular level with a local flavour. In the very first issues of the magazine, in fact, hallowed names of modern architecture alternated with the anonymous beauty of indigenous constructions.18 In displaying its editor’s interest both in the contribution made by folk art to the transformation of the landscape and in the impact of “tropicalism” on modern architecture, Habitat also represented the primary arena politicizing an intellectual stance, which would take Lina Bo Bardi to Salvador de Bahia, in the late 1950s, in search of cultural phenomena among the peoples of the nordeste.19

In several respects, Habitat undeniably represented the ideal tool kit for the intellectual in a class of her own, whom its first editor was. The magazine’s multi-disciplinarity, as a creative and critical principle, tallied perfectly with the approach of an architect who, having actually built relatively little, found expression in a multi-facetted and eclectic range of activities which was in no way confined to architecture, in the strict sense of the term. In other respects, in the magazine’s very format, as an organized medium and a composite forum for debate, we find that particular feature which Marcel Ferraz identified as essential in the poetics of Lina Bo Bardi: a marriage between rigour and freedom.20 In Habitat, more than in anything else created by the architect, in fact, the rational discernment making it possible to embrace different periods, disciplines and value systems within a coherent framework was combined in an extremely successful way with the carefree nature of the imagination, rid of prejudice and beyond all forms of dogmatism.

Cecilia Braschi is an art historian and PhD student at the Université de Paris I. Her research focuses on European and South American abstract art movements after 1945, and the artistic networks between these two continents, in particular through specialized periodicals. In charge of research at the Fondation Giacometti from 2005 to 2012, she has also published several studies of Alberto Giacometti. Since 2015, she has been responsible for exhibitions for the Hôtel de Caumont Centre d’Art in Aix-en-Provence.

“Ambiente, dignidade, conveniência, moralidade de vida, e portanto espiritualidade e cultura”, “Prefácio”, Habitat, December 1950, no 1, p. 1.

2

Mário Pedrosa, “Brasília, a cidade nova” [paper delivered to the Congrès international des critiques d’art], Jornal do Brasil, 19 Sept. 1959. Republished in: Mário Pedrosa, Dos murais de portinari aos espaços de Brasília, São Paulo, Perspectiva, 1981, p. 345-353.

3

Pietro Maria Bardi (1900-1999) was, notably, the founder, with Massimo Bontempelli, of the magazine Quadrante and director of the Galleria di Roma, in the 1920s.

4

She was temporarily replaced by Flávio Motta for issues 10-13, and then permanently replaced first by Abelardo de Souza, then by Geraldo Ferraz.

5

In particular thanks to the MoMA publication: Brazil Builds (1943), which Lina Bo was acquainted with before she arrived in Brazil.

6

42.5 x 29 cm.

7

From 1954 on, however, when Lina Bo Bardi was no longer in the editor’s seat, Habitat called itself, in its subtitle, an “architectural review”.

8

“Função artisticamente social”, in “Prefácio”cit.

9

See in particular: “Um restaurante”, Habitat, March 1951, no 2, p. 28-29. “Museu à beira do Oceano”, Habitat, 1952, no 8, p. 6-11. “Residência no Morumbi”, Habitat, November 1953, no 10, p. 36-41.

10

“Moveis novos”, Habitat, November 1950, no 1, p. 53-55. “Nova poltrona”, Habitat, September 1953, no 12, p. 36-37.

11

“Ourivesaria”, Habitat, March 1952, no 6, p. 34-35.

12

We refer all the same, for the most important, to: Silvana Rubino and Marina Grinover (eds.), Lina por escrito. Textos escolhidos de Lina Bo Bardi, São Paulo, Cosac & Naify, 2009.

13

Lina Bo Bardi, “Primeiro: escolas”, Habitat, September 1951, no 4, p. 1.

14

Lina Bo Bardi, “Bela criança”, Habitat, March 1951, no 2, p. 3

15

Preface by Lina Bo Bardi to: Max Bill, “O arquiteto, a arquitetura, a sociedade”, Habitat, February 1954, no 14, n. p.

16

See in particular the article by Lina Bo Bardi, “Função social dos museus”, Habitat, December 1950, no 1, p. 17.

17

On this, see: “Nao começamos pela forma”, interview of Marcelo Ferraz by Raíssa de Oliveira, republished in: Marcelo Ferraz, Arquitetura conversável, Rio de Janeiro, Azougue, 2011, p. 161-178.

18

See in particular: “Amazonas. O povo arquiteto”, Habitat, December 1953, no 1 and Cirell Czerna, “Porque o povo é arquiteto?”, Habitat, June 1951, no 3.

19

On this see: Eduardo Pierrotti Rossetti, Tensão moderno/popular em Lina Bo Bardi: nexos de arquitetura, Universidad Federal da Bahia, Salvador da Bahia, 2002.

20

Marcelo Ferraz, Arquitetura conversável, op. cit.

Cecilia Braschi, "Lina Bo Bardi and the magazine Habitat." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/lina-bo-bardi-and-the-magazine-habitat/. Accessed 15 July 2025