Research

Evelyn Cameron, Buckley sisters roping cow, April 9, 1914, black and white nitrate film, 5 × 7 in. (12.7 × 17.8 cm), Photos used by permission from the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives

It is our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our multiplying millions. The vast and limitless future will be the age of American greatness.

— John L. O’Sullivan, United States Magazine and Democratic Review (July 1845)

In 1803, during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, the United States acquired 828,000 square miles of North American territory from France, in what became known as the Louisiana Purchase. This land acquisition doubled the nation’s size and set the stage for future settlement across the continent. Four decades later, journalist John L. O’Sullivan coined the phrase “Manifest Destiny” in reference to his support of Texas’s annexation, which ultimately expanded the US territories further. This term gave ideological form to this westward expansion by white settlers. The belief that the United States was divinely destined to spread across the continent justified conquest, migration, and the transformation of western lands into farms, ranchlands, and settlements.

Federal legislation reinforced this vision. The Homestead Act of 1862 offered free plots of land to settlers willing to live on and cultivate them, embodying the logic of Manifest Destiny in law. While the Act opened opportunities for thousands of migrants, along with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, it also accelerated the dispossession of Indigenous peoples and reconfigured the demographic and cultural landscape of the northern plains and mountain regions. In areas that would become Wyoming and Montana—territories carved partly from the Louisiana Purchase—homesteading, ranching, and resource extraction transformed Indigenous homelands into settler frontiers.

The vast physical geography of the west—its mountains, plains, and open skies—became as central to the American imagination as the political rhetoric of Manifest Destiny. Simultaneously, the lived reality of the Indigenous communities persisted, despite being erased from the dominant narrative. As historian Greg Grandin reminds us, the frontier served as a “powerful symbol of American universalism,” promising that “the brutality involved in moving forward would be transformed into something noble.”1

Later, the emptiness imagined in those sweeping vistas, paired with the erasure of Indigenous peoples, laid the foundation for the mythology of the “American West.” In the decades that followed, artists, photographers, and eventually filmmakers, transformed land and people alike into symbols: wilderness as freedom, and the Indigenous peoples as nostalgic archetypes of the frontier. By situating conquest within a visual frame of vanishing “Indians” and boundless landscapes, the West was turned into a cultural stage as much as a historical region. This tension between lived history and constructed myth makes visual culture central to how the West is understood.

While national policy and ideology shaped the broad outlines of westward expansion, life on the frontier was equally defined by local experiences and the people—particularly women—who documented them. Women played a central role as wives, mothers, ranchers, entrepreneurs, and teachers, sustaining households and establishing the institutions of community life in often harsh and isolating landscapes. Many turned to creative expression—through painting, photography, and writing—as a way to document and interpret the world around them. The work of these women is often in contrast to the most famous examples from art history that portray western expansion.

John Gast, American Progress, 1872, oil on canvas, 29.2 × 40 cm, Autry Museum of the American West

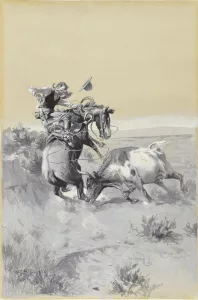

Charles M. Russell, A Moment of Great Peril in a Cowboy’s Career, c. 1904, Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite underdrawing on paper, 24 × 16 in. [61 × 41 cm], Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection

Many of these examples, exemplified by John Gast’s 1872 painting American Progress, “drew a veil over aspects of frontier life that were unsavory or simply mundane. Artists skated over the low points of the historical record—economic disasters, mining busts, droughts, depredations of the land, decimation of the buffalo herds, near obliteration of Indian cultures—with a consoling rhetoric of grand purpose.”2 Between the era of grand allegorical paintings that celebrated westward expansion and the later Hollywood westerns that romanticized the cowboy, women’s records of homesteading, ranching, and community building offered a more grounded image of frontier life. Their images often revealed the daily realities of settlement—family life, labor, quiet western landscapes, and community—rather than the simplified legends of conquest or the cowboy that would later dominate 20th-century film.

Examining women’s artistic work through both painting and photography underscores the very different challenges and opportunities of each medium. Painting drew on centuries of tradition, canonical standards, and academic training, often inflected by European influence. Photography, by contrast, was a young and unstable technology that required ingenuity: fragile supplies had to be transported long distances, darkrooms improvised, and processes mastered largely without formal instruction. In lieu of any clear artistic canons, it often produced images that appear raw and unfiltered, shaped as much by circumstance as by choice.

Both mediums gave frontier women artists the power to be selective in what they depicted, but in very different ways. Painting allowed refinement or “perfection” of a subject, situating Western themes within established artistic traditions. Photography, especially in isolated regions such as Montana and Wyoming, could capture frontier life with stark immediacy. In the work of Evelyn Cameron (1868–1928) and Lora Webb Nichols (1883–1962), this quality is especially evident: E. Cameron’s images of ranch labor and L. W. Nichols’s portraits of family and community convey the era with a rare directness, complementing the interpretive refinements made by their counterparts in painting.

E. Cameron and L. W. Nichols exemplified the resourcefulness required to practice photography in remote frontier conditions. The former documented ranch work and landscapes with clarity, turning everyday labor into enduring record, while the latter created thousands of portraits and domestic images that captured the intimacy of family and community life. Their work emphasized endurance, adaptation, and social connection—qualities often absent from mythologized depictions of rugged isolation.

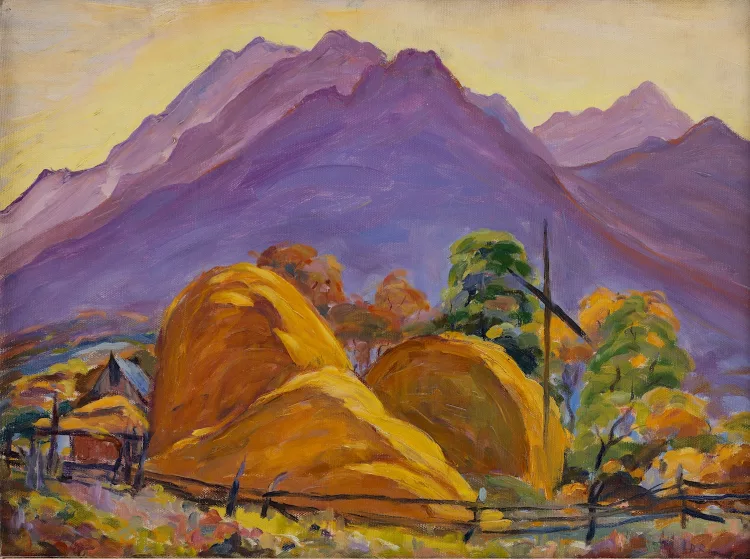

In painting, Fra Dana (1874–1948), Josephine Hale (1878–1961), and Elizabeth Lochrie (1890–1981) engaged with a medium bound by a long tradition yet adaptable to new contexts. Dana, who trained in Europe, brought Impressionist sensibilities to Montana landscapes, blending international styles with local subject matter. J. Hale and E. Lochrie, working within academic frameworks, explored themes of place, identity, and cultural encounter. Unlike photography, which preserved immediate realities, painting allowed these women to interpret the West more flexibly, situating regional experiences within broader artistic traditions while also emphasizing the distinctiveness of Western themes.

The works in this exhibition reveal how women artists balanced two seemingly opposite impulses: to document the ordinary rhythms of daily life and to express their fascination with the vast landscapes and cultural encounters of the West. E. Cameron and L. W. Nichols, for instance, turned their cameras toward the everyday. Nichols’s portraits of families on porches or friends gathered in small-town Wyoming preserve the texture of community life that is often overlooked in narratives of the West. E. Cameron’s images of ranch labor—women carrying buckets, women preparing saddles and bridles—make visible the quiet perseverance that structured frontier survival. These photographs root the story of the West in the mundane, showing not conquest or heroic destiny but the routines that made life possible.

Fra Dana, Breakfast, date unknown, oil on canvas, 23 1/4 × 19 1/2 in. [59 × 49.5 cm], gift of Fra Dana, Courtesy of the Montana Museum of Art and Culture

Alongside these grounded records are works that point toward wonder. F. Dana’s paintings, such as Breakfast, situate domestic interiors within Impressionist light, transforming humble rooms into luminous scenes of cultural refinement. E. Lochrie, by contrast, painted portraits of Indigenous subjects that reflected both her admiration and the era’s ethnographic fascination with cultural difference. Even in F. Dana’s and E. Lochrie’s differing approaches, we see women artists using painting to elevate their subjects—whether domestic or cultural—into works that anchor the West within a broader historical and artistic tradition.

To view these works together is to recognize that the American West that grew from the Manifest Destiny era was never singular. It was at once ordinary and extraordinary: a place of relentless daily labor and a landscape that inspired awe. The photographs of E. Cameron and L. W. Nichols ground the West in its material realities—buckets of water carried across dusty yards, families gathered in cramped interiors, friendships documented on porches. By contrast, F. Dana’s Impressionist-inflected interiors, J. Hale’s landscapes, and E. Lochrie’s portraits of Indigenous sitters point toward the region’s capacity to evoke wonder, cultural encounter, and artistic transformation.

What makes these works powerful is not only what they depict but also how they shift our understanding of the West itself. Women’s creative records interrupt longstanding mythologies, insisting that the West was transformed through endurance, care, adaptation, and the work of community. Seeing these photographs and paintings together today allows us to imagine the frontier not as a heroic stage for national destiny, but as a lived environment shaped by many voices. In that sense, the women represented here offer not just historical evidence but an enduring reminder that visual culture defines how we remember, interpret, and define a sense of place. The very emptiness imagined in the landscapes of the West—so central to the myth of American destiny—was never empty at all, and the works of these women remind us how much was lived, recorded, and remembered there.

Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019).

2

Elizabeth Broun, “Foreword,” in The West as America Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920, ed. William H. Truettner (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991).

Publication as part of the exhibition Women Artists of the American West: Trailblazers at the Turn of the 20th Century

Nicole Jean Hill, "Everyday West: Female Vision Beyond the Myth." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/louest-quotidien-une-vision-feminine-au-dela-du-mythe/. Accessed 27 February 2026