Interviews

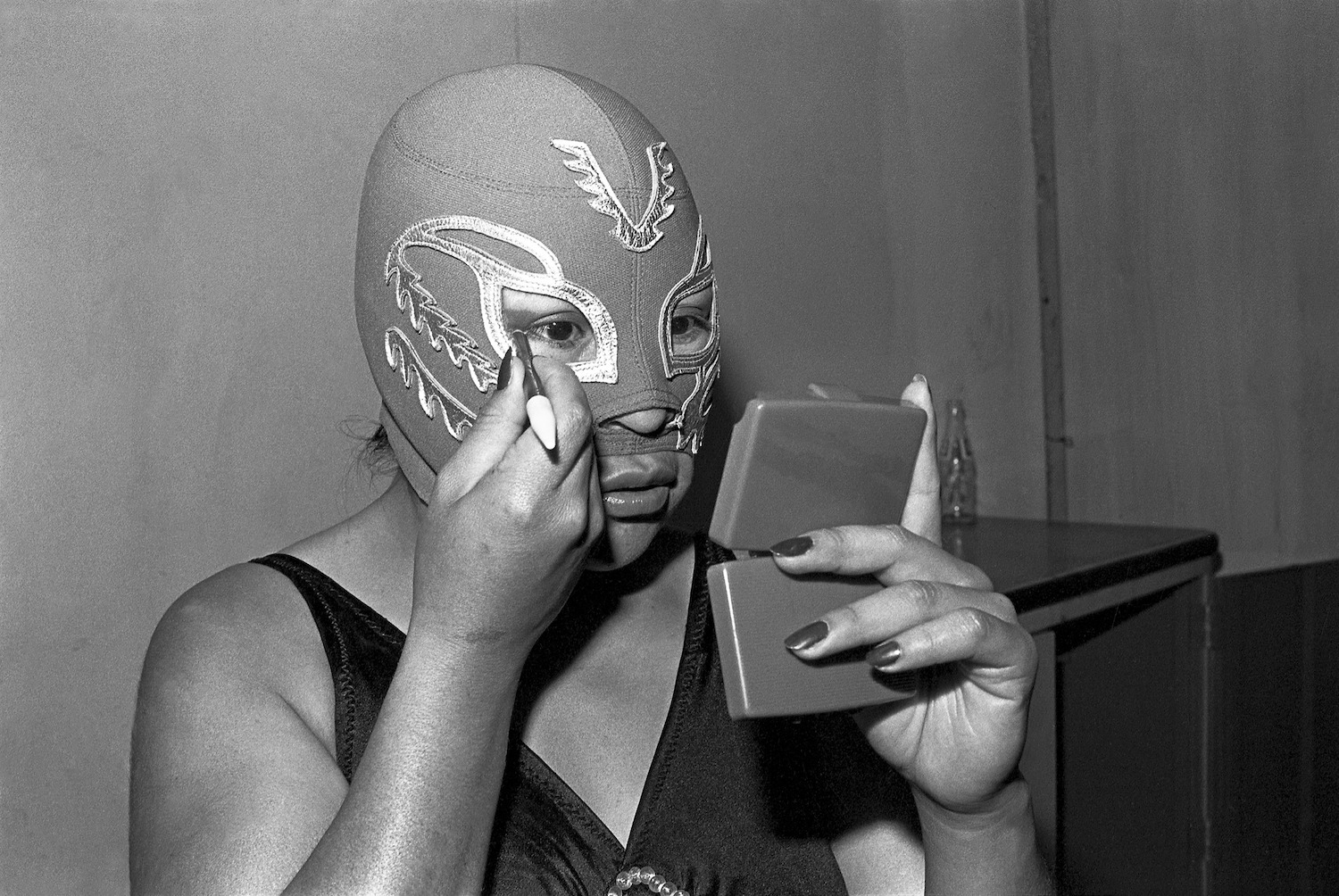

Lourdes Grobet, La Venus [The Venus], black-and-white photograph, 24 x 35.5 cm (9 1⁄2 in x 14 in), from the series La doble lucha [The double struggle], 1981-2005, Collection of the artist

Born in 1940 to a Swiss-Mexican family, artist Lourdes Grobet is the product and inheritor of several schisms in the art world of 20th-century Mexico. Her body of work is wide-ranging, though largely based in photography, and pushes back against nationalism and the forces of the art market, both rejecting and forming itself in opposition to several leading art Mexican art movements of the first half of the 20 century.

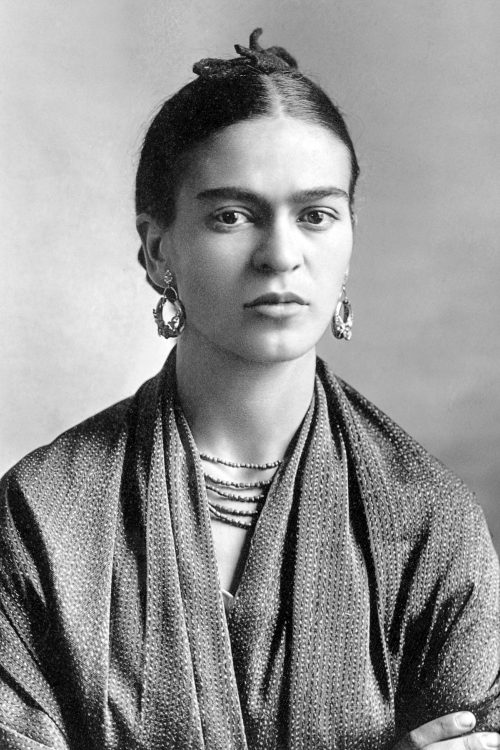

When discussing and writing on her work, L. Grobet frequently mentions her mentors and influences as a young woman in Mexico City and while studying at La Universidad Iberoamericana. Her instructors and educators formed an amorphous group of anti-academic artists seeking to reject the semi-official, highly political muralism style that had dominated the nation’s art since the end of the Mexican Revolution. One of L. Grobet’s influences was Gilberto Aceves Navarro (1931-2019), a painter associated with the Ruptura generation of artists who sought to create space for less dogmatic, less nationalistic art forms. Equally she is the product of European-born artists Mathias Goeritz (1915-1990) and Kati Horna (1912-2000), both of whom were driven to Mexico as a result of the Second World War. M. Goeritz and K. Horna formed part of a loose expatriate community of artists, largely separate from the Mexican Ruptura generation, who brought their own interpretations of modernism to a Latin America. K. Horna applied her highly aestheticized version of photographic Surrealism to a Mexican context, while M. Goeritz developed a design style called Emotional Architecture, which eschewed politics and functionalism in favour of an abstracted idea of post-war spiritual renewal.

L. Grobet integrated components of her various mentors’ work and approaches and created a distinct visual language concerned with technology, the distribution of media, Mexican politics, gender and social class. Her art aims to be provocative and unapologetic in addressing previously overlooked subjects and themes. L. Grobet’s early involvement in the avant-garde collective Proceso Pentágono (1969-1976) based in Mexico City, positioned her on a distinctly anti-institutional path, and coincided with her creation of independent, experimental media happenings, including Hora y Media [Hour and a half, 1975]. Later, L. Grobet focused her camera lens on rural, mostly indigenous theatre troupes and lucha libre fighters, seeking to reframe subjects she saw as patronized, exploited or forgotten in Mexican visual culture. And while she doesn’t identify as a feminist artist, much of her best-known photography gave agency and voice to working-class, female subjects. Brave and uncompromising, L. Grobet has spent her life creating work on her own terms, becoming an influence for younger generations of experimental Mexican artists who engage with radical politics, public space, and disparate subjects and themes.

Miller Schulman:

It is such an honour to speak with you about your life and work. To begin our conversation, I wanted to ask you about your influences as a young person. From what I’ve read about you – as well as what you’ve said about your work – your mentors played an outsized part of your formation as an artist. In particular you were very close to the artist and architect Mathias Goeritz. What was it like being his protégé?

Lourdes Grobet:

Mathias was trying to build an anti-academy at La Universidad Iberoamericana. These professors were the first people who began to talk to me about multimedia work. This was the 1960s, and multimedia and technology were beginning to become important in art. Mathias was the first person who began speaking to me in terms of media. His influence prompted me to go to Paris in 1965 where there was an explosion of kinetic art. I still think about all the work I saw during my brief time there. I then came back to Mexico and burnt all of my paintings and drawings.

MS: You literally burnt them?

LG: Yes! Like a renovation of myself. And I didn’t become a kinetic artist, but I decided at the time to become a photographer. With a camera you could create images that involved technological advancement. I felt like I needed to use technology to create my images. At university we studied critical media theory, especially that of Marshall McLuhan. Because of Mathias, and because of Kati Horna, well, they saved my life. They put me on the right track. Well, that’s at least what I think.

Mathias told me all the time, “If you don’t enjoy your life with art, then forget about it. And don’t take yourself too seriously.” Those two statements really guided my development as a young artist. That’s why he was my true mentor and teacher.

MS: I think it’s interesting that, after the events of 1968 in Mexico, Mathias Goeritz became very quiet and scaled back his work. Whereas you became much more political in your associations and work. For example, you were a member of Proceso Pentágono.

Lourdes Grobet, Cuarto de tortura [Torture room], image from a Proceso Pentágono, installation, c. 1975

LG: Mathias and I remained close until his death. He was consistently avant-garde. But yes, he was not involved in politics. It was different for me. I went to study in England, and when I came back, it was the 1970s. I met Felipe Ehrenberg (1943-2017), a founding member of Proceso Pentágono, and we became partners and started living together. This was the beginning of Proceso Pentágono, when many of its members were coming back from living in France. They soon invited me to join the group. And this was a good fit, because I had an inherent leaning towards politics. It had been in me since I was a young woman. But not in the “working for a political party” way of speaking.

My political inclinations were towards working for the needs of people and working in the streets. Joining the group was wonderful because we started working for another cause. Our work was shown and created on the streets and in unofficial artistic spaces. And I think the work that we did was very important. I liked working in this group because it offered anonymity.

MS: You both sought and continue to seek out anonymity? You think that’s desirable?

LG: Yes, many heads think better than one. That anonymity in a group is very useful and good. It’s not a singular idea. A group rejects the figure of the protagonist.

Lourdes Grobet, Hora y media [Hour and a half], 1975, photo performance, three black-and-white photographs, 160 x 105 cm (63 x 41 1/16 in each), Courtesy of the artist

MS: In 1975 you and Marcos Kurtycz (1934-1996) created the performance piece Hora y media [Hour and a half] at the Casa de Lago in Mexico City. Was this part of Proceso Pentágono?

Lourdes Grobet, Hora y media [Hour and a half], 1975, photo performance, three black-and-white photographs, 160 x 105 cm (63 x 41 1/16 in each), Courtesy of the artist

LG: As part of Proceso Pentágono we were encouraged to focus on our own work too. And I never stopped doing that, even after I joined the group. But yes, that piece: we didn’t call it performance. We called it a happening. For Hora y media I was trying to show to the public how a photograph was created. So I built three boxes, and I came out of each. A friend was photographing this entire action. I took my enlarger to the gallery, installed safety lights, and developed them in the gallery space. But I didn’t fix them. I hung the enlarged images up, and turned on the regular lights, so the three images were immediately overexposed and disappeared.

Lourdes Grobet, Hora y media [Hour and a half], 1975, photo performance, three black-and-white photographs, 160 x 105 cm (63 x 41 1/16 in each), Courtesy of the artist

There were two guiding ideas behind this project. One was, following Mathias’s advice to not take yourself too seriously. I saw photographers presenting highly edited images around this era, which went against my idea that photography should be a multimedia, experience piece of art. I never edited my photographs. Because for me photography is a mass media. The more I can print and produce, the happier I am. The other meaning was that, with light, you can create or destroy. My friends in the collective understood this impulse, but many photographers who came got annoyed.

MS: Destruction and rejecting preciousness seem to be very important components of your practice.

LS: Since I began making art, I never sought out fame or affirmation. I just wanted to make art, and that’s what I have been doing all my life. Many people haven’t been happy with the work I’ve produced.

Lourdes Grobet, Tania la guerrillera y Reina Gallegos, photograph, from the Lucha Libre [Free Fight] series, Courtesy of the artist

MS: Had you already started on your series Lucha Libre [Wrestlers, 1980-2003] when you created the Hora y media happening?

LS: No, I started work on the Lucha Libre series in 1980.

MS: I recently read an essay by Esther Gabara, “Fighting it Out: Being ‘Naco’ in the Global ‘Lucha Libre’”, on your work in relation to the history of professional wrestling in Mexico. She wrote that general interest in lucha libre spanned the working and middle classes in the 1940s and 1950s, but this changed in the 1960s and 1970s, when more bourgeois circles began to turn away from Mexican popular culture. She claims that your work is a confrontation of these class-based changes in taste and culture.

LS: I had been interested in lucha libre since I was a little girl. My father was Swiss, and very interested in athletic activity, but he never took me to the lucha libre matches, no matter how much I asked. This had nothing to do with social class. That term didn’t exist in our household. The problem was that I was a girl, so I never went while I was growing up. Later on, when I was experimenting with my camera, I went to the matches to see them for myself. And something happened to me. I was so astonished with the events. And I decided that I would focus a large part of my efforts on lucha libre because here I saw what I thought was real Mexican culture.

At this point, in my photographs I didn’t want to depict a tedious, overdone vision of Mexico. But there, in the wrestling ring, I found the real Mexico. Being there was very important to me because I didn’t and still don’t feel very Mexican at all. But the organizers of the fights were annoyed with me at first, because they had never had a woman photographer doing what I was doing. But I told them how much I wanted and needed to be there, and eventually they understood and gave me a special permit.

Soon many doors started to open for me. There was a whole world beyond the wrestling ring. And there is so much history in these wrestling rituals. Masks are a common link in Mexican history, linking the pre-Columbian past to the present, for example the Zapatistas. Playing with and veiling one’s identity was central to my work.

MS: Once again you’re talking about anonymity and putting distance between oneself and their work, whether artistic, political, or in the wrestling ring. Did you become close on a personal level with the lucha libre fighters?

LG: Yes, I started photographing the fights, then the spectators, and then the fighters, in particular the women. Many of them couldn’t make a living only through the fights, so they had to have other jobs. I went to see them at home and in their places of work, and the resulting photographs, of the lives these women were leading to sustain their life in the wrestling ring, were titled Lucha por la vida (Fighting for life).

After visiting and getting to know these fighters over the course of many years, I came to realize that there were essentially no books published on lucha libre.

MS: Why is that?

LG: Well, nobody cared. Many people working in art and culture at the time thought these were spoiled poor people. Whatever that means. Today it’s completely different. It’s a fashionable intellectual topic, and every week I get emails asking for interview requests. I like to think that the book I published of my Lucha Libre photographs in 2005 opened this subject to newer audiences and social classes in Mexico.

Lourdes Grobet, La Tragedia del jaguar [The Tragedy of the Jaguar], photograph, from the series Laboratorio de Teatro Campesino [Laboratory of Peasant Theatre], 1984-2018

MS: Was your thinking behind your extended project Laboratorio Teatro Campesino [Laboratory of Peasant Theatre, 1980s] at all similar?

Lourdes Grobet, La Tragedia del jaguar [The Tragedy of the Jaguar], photograph, from the series Laboratorio de Teatro Campesino [Laboratory of Peasant Theatre], 1984-2018

LG: Ah, yes, another extensive project of mine. What happened with that project was that I took my playwright friend to see the lucha libre fights. And he hated it and was furious with me. He told me, “I am going to take you to see real theatre.” In 1986 he took me to the state of Tabasco, where there was a big explosion of Teatro Campesino. The governor of Tabasco at that time was an intellectual, and there was a lot of government support for this type of regional, folkloric theatre. When I saw these performances, it was the same feeling I experienced when I first saw the lucha libre. In these images, I sought to create a contrast between Mexican urban and rural popular cultures. I wasn’t taking photographs of indigenous people per se; I was taking photographs of cultural paradigms. This was an incredible life experience. Many of these actors are still alive, and are still my friends, and continue to work as actors. This has been an incredible, long-term project for me, spanning over thirty years of my life. Finally, after eight years of lobbying, it looks like the Mexican government is going to publish a volume of these photos.

MS: I want to ask you, before we conclude this interview, what Mathias Goeritz would think about the work you have created? Do these projects reflect his mentorship and influence?

LG: Mathias, I think, would be very happy knowing that my work and life has always been based around pursuing freedom in all its forms.

[This interview has been edited and condensed.]

Born in 1940 to a Swiss Mexican family, artist Lourdes Grobet is the product and inheritor of several schisms in the art world of 20th century Mexico. Her body of work is wide-ranging, though largely based in photography, and pushes back against nationalism and the forces of the art market, both rejecting and forming itself in opposition to several leading art Mexican art movements of the first half of the 20th century. Her subjects of interest range from Lucha Libre fighters to painted, geological interventions.

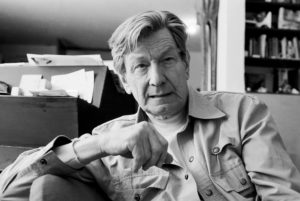

Miller Schulman is a writer and researcher whose interests span from Latin American Modernist architecture to queer theory and literary criticism. He holds a Masters of Philosophy in the History of Art + Architecture from the University of Cambridge, and a BA in History from Tufts University (MA). He previously worked at kurimanzutto gallery in Mexico City, and his writing has appeared in Vogue Latin America, Pin-Up Magazine, Flaunt Magazine, among others.

An article produced as part of AWARE’s academic network, TEAM: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.