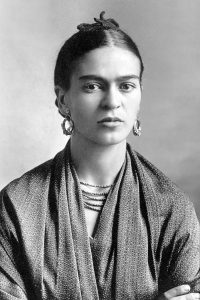

Frida Kahlo

Kahlo Frida, Le Journal de Frida Kahlo, Paris, Éditions du Chêne, 1995

→Herrera Hayden, Frida : biographie de Frida Kahlo, Paris, Le Livre de Poche, 2003

→Jamis Rauda, Frida Kahlo autoportrait d’une femme, Arles, Actes Sud, 1999

Frida Kahlo, Tate Modern, London, 9 June–9 October 2005

→Frida Kahlo: A Life in Art, Arken Museum, Ishøj, 7 September 2013–12 January 2014

Mexican Painter.

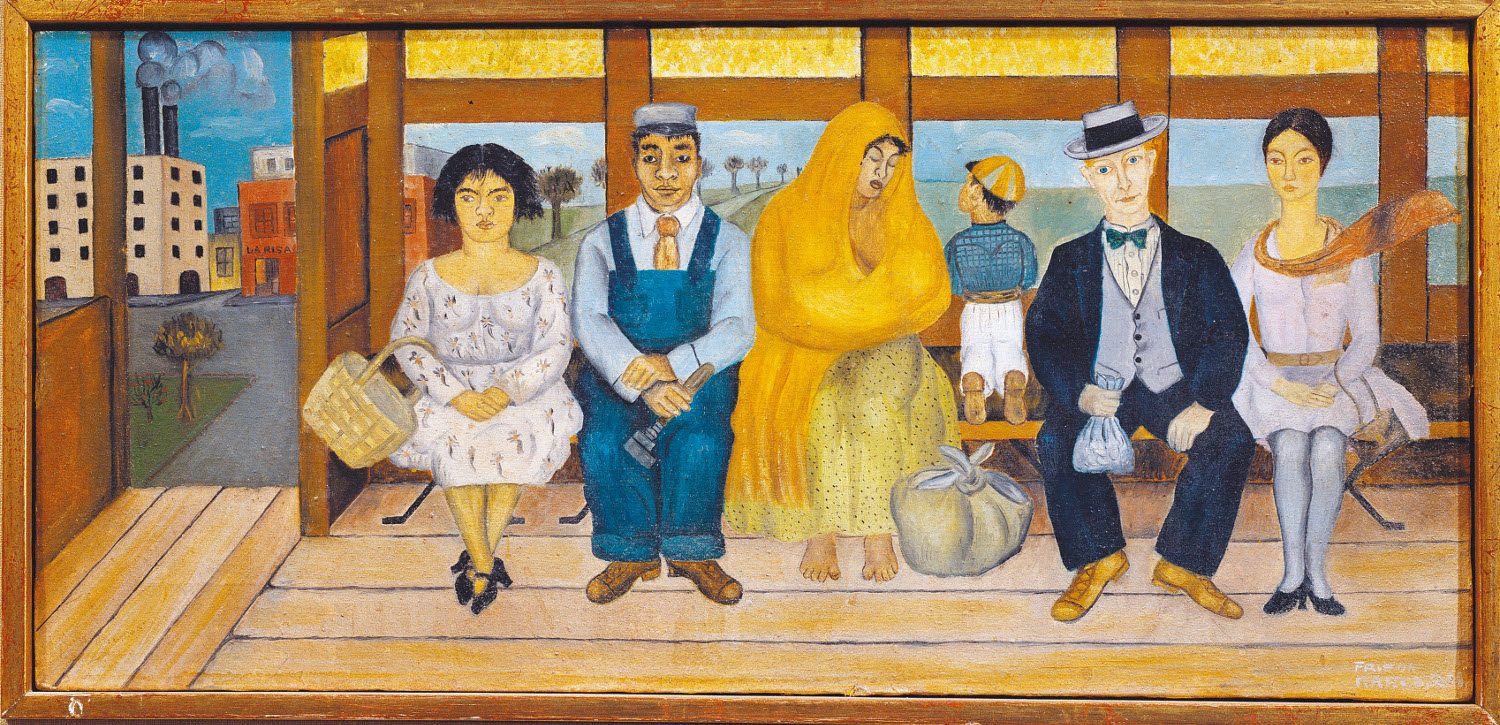

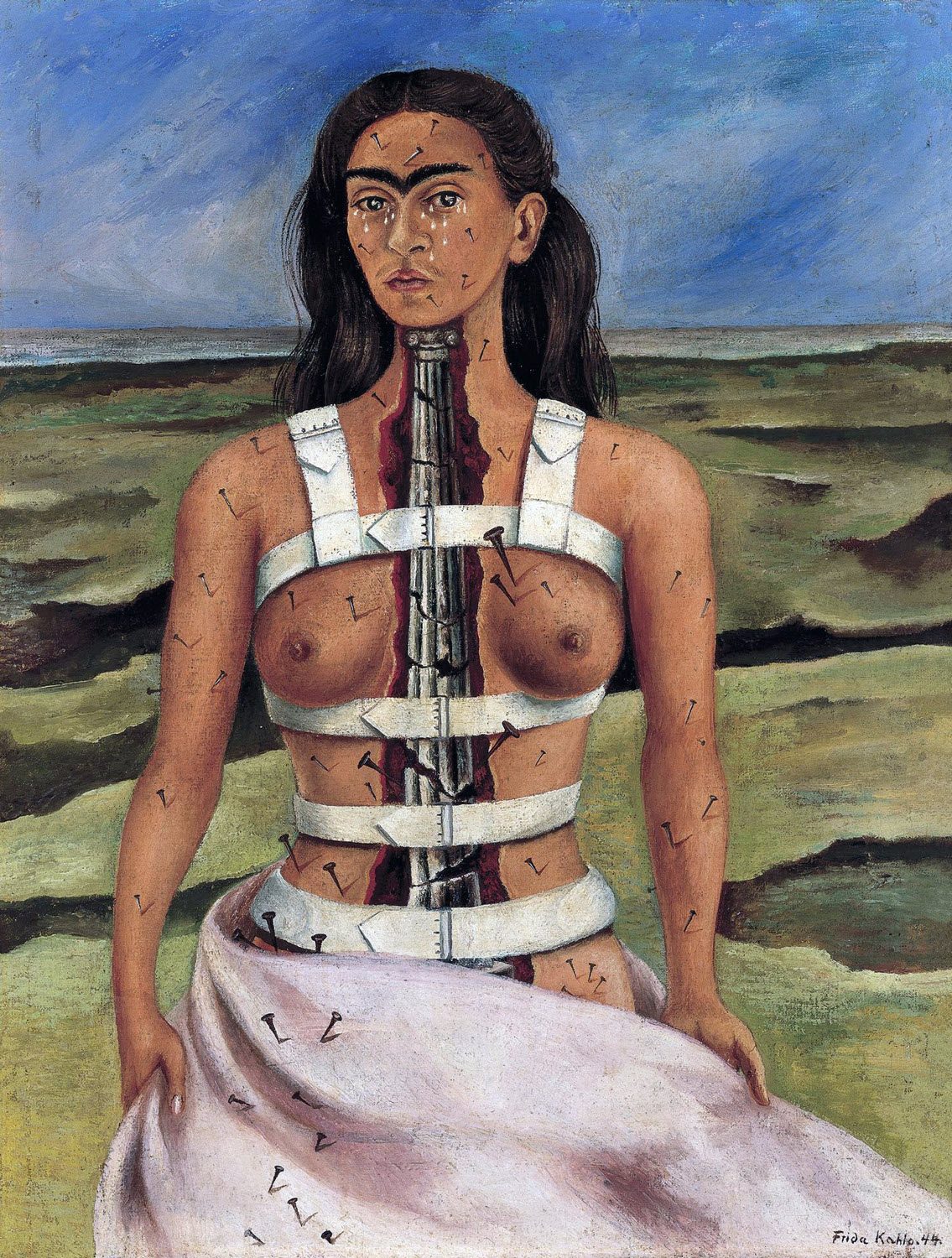

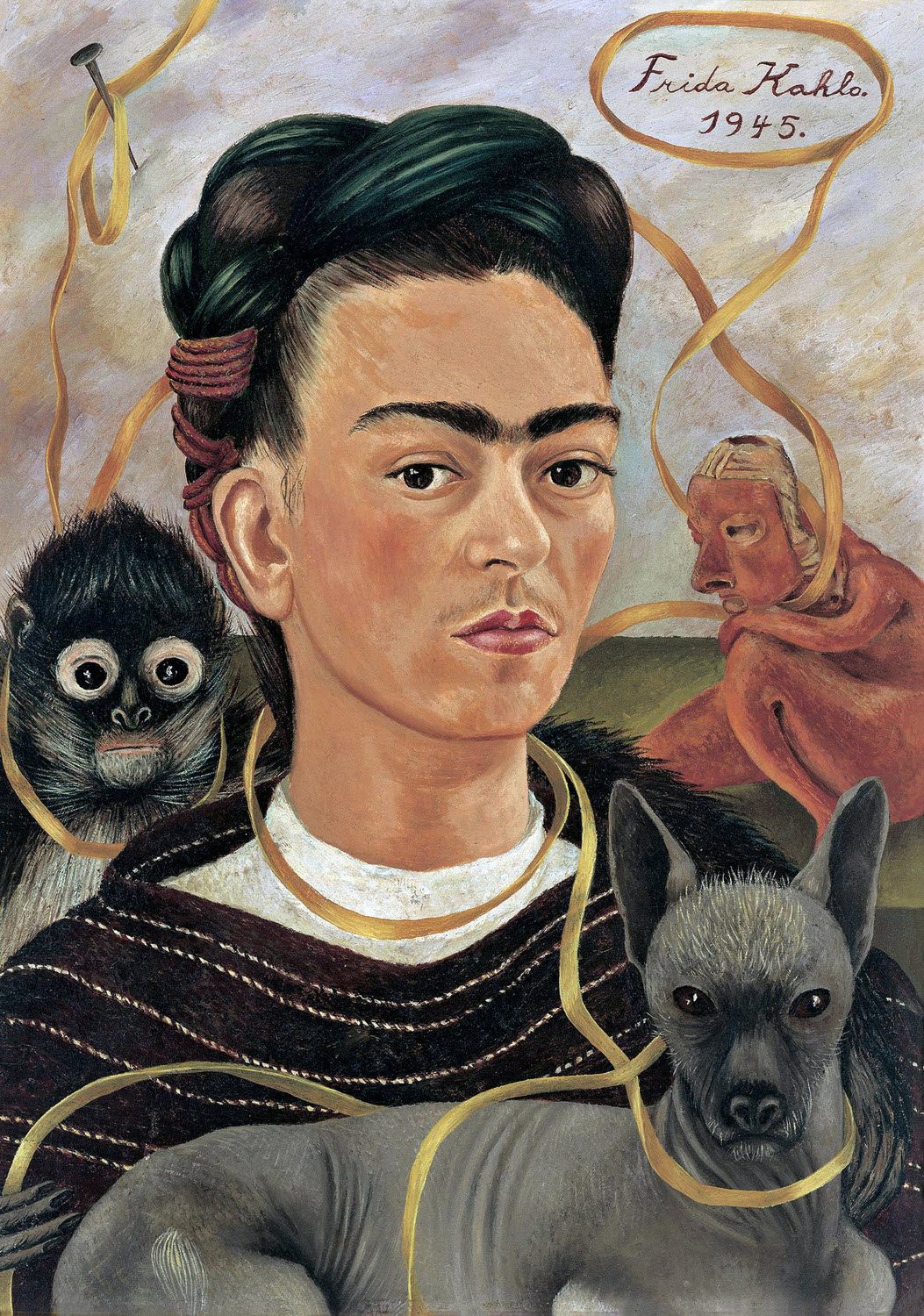

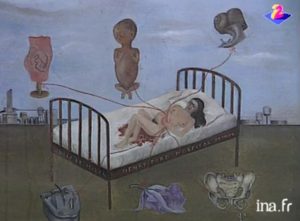

Frida Kahlo began her art career learning photography and photo color retouching from her photographer father. In 1925, a violent bus accident nearly killed her; its effects would linger for the rest of her life, and echo through her work. Her long period of immobility forced the young, energetic woman to turn to one of the only activities that she could do from her bed: painting. Child of the modern Mexican Revolution (1911), and sometime member of the communist party, she was a devoted activist, inspired by the example of the photographer Tina Modotti. In 1929, she married a giant of Mexian painting: Diego Rivera. Always a free spirit, she embodied at once a commitment to modernity and a defense of la mexicanidad, most notably through her trademark outfits. Many elements of her life were profoundly affected by her childhood accident; for instance, all of her pregnancies ended in miscarriage. But if her oeuvre expresses an essentially painful relationship to her body, it is not to complain about the discomfort, but to exteriorize it in order to better dominate it, overcome it, and share it. Kahlo’s paintings seem to be in search of a cathartic liberation. Her work can be defined as a journal in paint; almost half of her production is comprised of self-portraits.

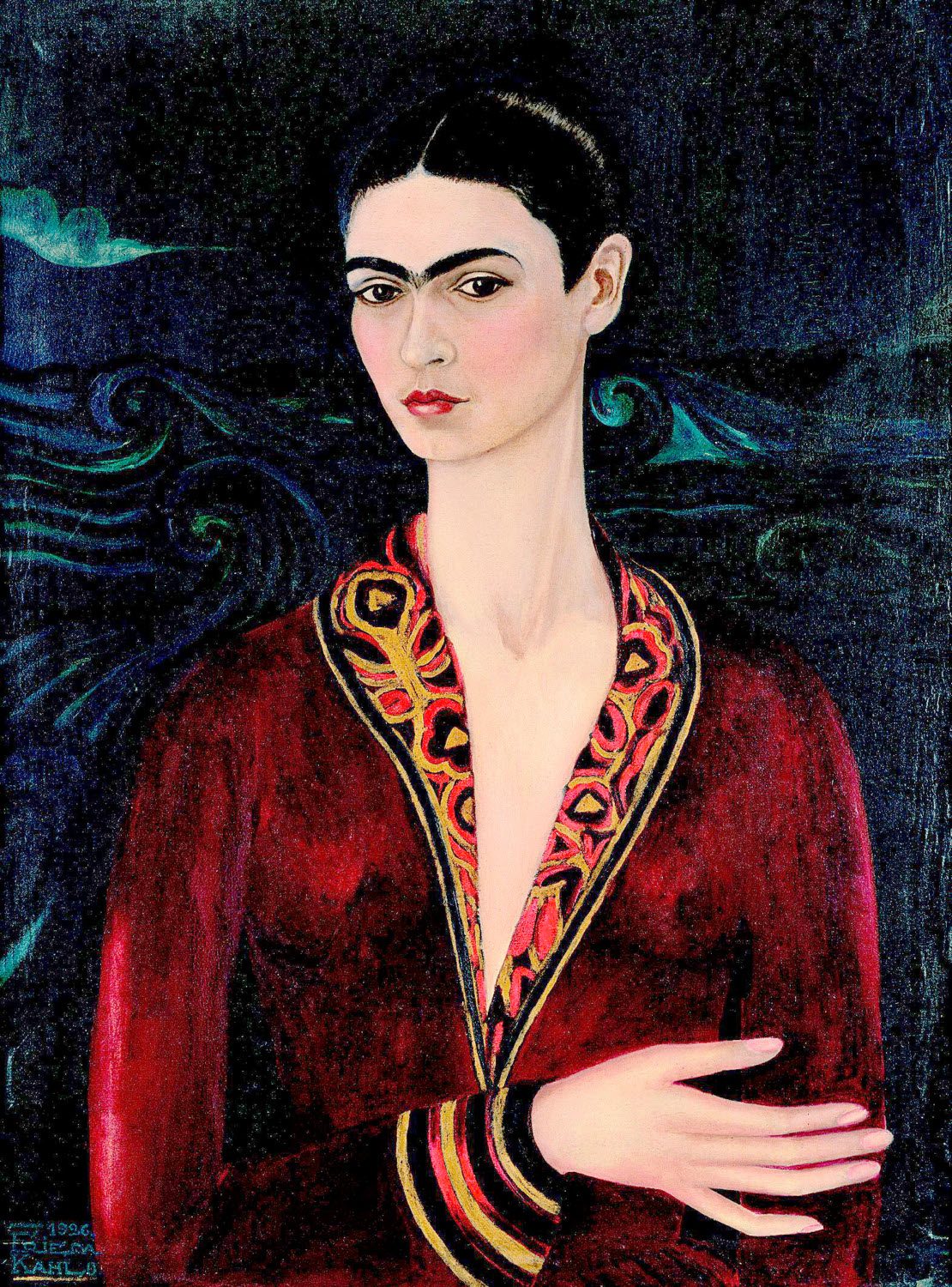

Her first significant painting, Self Portrait in a Velvet Dress (1926), carries the traces of her attentive study of the masters of the Italian Renaissance (particularly Bronzino and Parmigianino) while affirming the singularity of her personal style—miniaturist, with populist inspiration, and an intense prominence of the subject. Most of the paintings sublimate the most profound emotions of the artist. The logic that organizes the motifs on the canvas reveals images from deep within the artist’s imagination (simultaneous appearance of distinct times and places in the same piece). Writer and poet André Breton thought that Kahlo’s art blossomed into full-on surrealism, a label she rejected. Illness didn’t keep Kahlo from globe-trotting or romance. She seduced New York gallerist Julien Levy, the elegant photographer Nickolas Murray, and many others—men and women. While visiting Paris in 1939, she took little joy from meeting the artsts and intellectuals surrounding André Breton; only Marcel Duchamp garnered her praise. Upon returning to Mexico, she divorced Rivera. She then painted Las Dos Fridas (The Two Fridas) (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico, 1930), one of her largest and most famous works. The painting showed the two facets of the artist’s personality: two friends seated side by side on a bench, their two hearts linked by an exposed vein. On the right, the Mexican Frida claims and fiercely defends her culture; on the left, in a European-style dress, the emancipated Frida. With this richly metaphorical work, Kahlo freed herself from the suicidal tendencies that had wracked her during the breakup of her marriage. In the tradition of the votive offering to a saint in thanks for a blessing, she painted Self-Portrait with Dr. Juan Faril in 1951. It is at once a classic self-portrait of the artist in front of her easel, and an emblematic painting of the pain-filled fate of Kahlo. Seated in a wheelchair before an easel with a painting of her beloved doctor, Juan Faril, she holds a palette in her hand which is, in fact, her heart, and paintbrushes that are dripping with her blood. Painting with blood, painting with heart.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

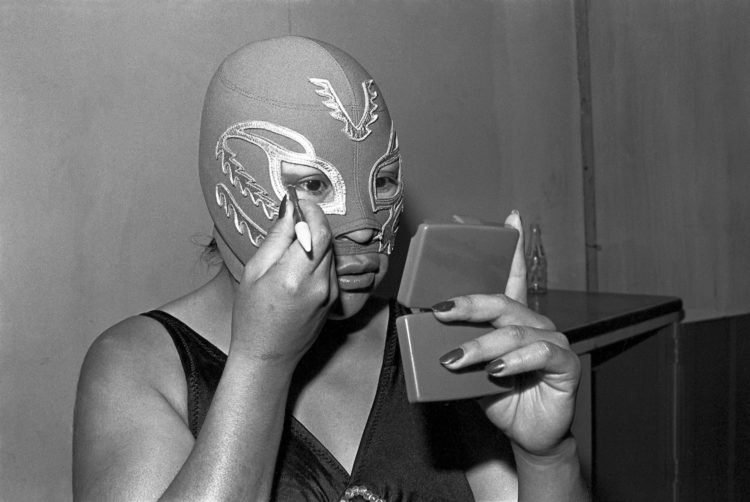

Exposition Frida Kahlo à Paris en 1992

Exposition Frida Kahlo à Paris en 1992