Research

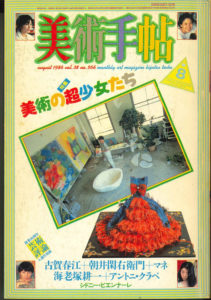

Cover of Bijutsu Techō, Tokushū : Bijutsu no chō-shōjotachi [Special issue: The ultra-girls in art], no. 566, Bijutsu Shuppansha, Tokyo, August 1986 © Bijutsu Shuppansha

In 1986, with the onset of the economic boom known as the “bubble economy”, the Japanese art world’s most influential publication, Bijutsu Techō magazine, released a special issue for their August edition. The issue, entitled Bijutsu no chō-shōjotachi [The Ultra Girls of Art, August 1986], reported on thirty-nine women artists active at the time. Today, anyone reading this title would raise an eyebrow at the use of a phrase like “ultra girls” to describe adult women. Nevertheless, the word “girl [shōjo]” offers us a glimpse of the stereotypical ideas—of “juvenility”, “innocence”, and “purity”—that men have about women. As a matter of fact, the then editor-in-chief of Bijutsu Techō was a man, but the editorial staff featured a gender-balanced system of three men and three women. What then was the purpose of this special issue? A postscript to the issue, penned by the editor-in-chief, reads as follows:

Cover of Bijutsu Techō, Tokushū : Bijutsu no chō-shōjotachi [special issue: the ultra-girls in art], No. 566, Bijutsu Shuppansha, Tokyo, August 1986 © Bijutsu Shuppansha

Among recent works of art, I have come to notice that the work of women artists is created through the sequential creation and multiplication of individual parts rather than via organised construction. This seems to have been based more on personal historical recollection than on a conscious effort to situate oneself within the broader perspective of art historical genealogy. In other words, it appears to be a living expression that has emerged directly out of their contemporary lives. It is my intention to imbue the term “ultra girls” with a meaning that is difficult to express through the terms “female artist” or “woman artist”, which are used to contrast them with men.1

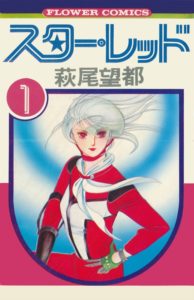

Thus, while the postscript states that its meaning is not meant to be used in contrast with men, it is not clear what the use of the term “ultra girls” is intended to convey. Originally, the term “ultra girl [chō-shōjo]” was popularised in artist, critic, and essayist Chizuru Miyasako’s 1984 book, Chō-shōjo e [Toward the Ultra Girl]. This book presents a critical discussion of the real-life circumstances of everyday girls, including C. Miyasako herself, through an analysis of the girls who appear in various literary and shōjo manga2 works. Most particularly, in Chapter Three, ‘Hi-shōjo’ kara ‘Chō-shōjo’ e: Hagio Moto o meguru kinmirai-teki shōjo ron[From ‘Non-Girls’ to ‘Ultra-Girls’: A Treatise on Moto Hagio’s Near-Future Girls‘]”, C. Miyasako analyses multiple works by Moto Hagio (1949-), who made her debut in the 1970s and revolutionised the shōjo manga genre. In this chapter, C. Miyasako vividly describes M. Hagio’s development of this genre character from the “girl”, who has been stripped of all independence and encased in a cocoon, and the “non-girl”, who is alienated because she knows the freedom of independence, to the “ultra girl”, who has the strength of spirit to remain independent, is empathetic to others, and rejects the masculine principle. Star Red, whose Martian protagonist is referred to by C. Miyasako as an “ultra girl”, was published in 1980. Hence, the term was originally utilised from a feminist perspective, but in the Bijutsu Techō issue, it was separated from C. Miyasako’s analytical context and has since taken on a life of its own as an extremely ambiguous concept.

Chizuru Miyasako, Chō shōjo e [Toward Ultra-Girls], hardcover, ©1989 東京 : 集英社, 1989 (Tokyo, Shueisha)

Nevertheless, let us now look at the actual content of this special issue, which had a certain impact at the time and is still occasionally referenced today. The issue is prefaced by the following words, which were written by the journal’s editorial department:

It is these young women who have been so remarkably active in the contemporary art scene, who have made the field of installation art significantly more flamboyant, and who have greatly advanced the acceptability of the materials used in their works. Their appearance has coincided with the process by which masculine history has hit its peak, and it clearly distinguishes them from the generation that sees being a woman as a handicap or a challenge to be conquered—to wit, the generation that attempted identity acquisition within the logic and systems of masculinity. In an era when men are no longer seen as the descendants of mythological heroes and women are no longer considered alter egos of the Great Mother [archetype], but rather a part of the modern, free human race, they show no hesitation in refining and shaping their own sensibilities without confining themselves to so paltry a mould as “girlish taste”.3

While there is the occasional expression that is difficult for us to agree with now, it is not the purpose of this article to judge a special issue published thirty years ago by the value system of today. It must be noted, however, that this statement is written from a consistently male perspective.

The names of thirty-nine women artists are listed adjacent to the editors’ statement, and each of the artists is introduced on the following pages with artworks, photographic portraits, and short biographies. In addition, nine of the artists are featured in one-page atelier visit articles, each written by one of nine women who were either editors or curators, or who specialised in art history or art criticism. Of these discussions of visited artists and analyses of their works, only Fusako Araki, who covered Mika Yoshizawa (1959-), writes with a somewhat impartial air: “In recent years”, she states, “‘feminist theory [josei ron]’ and ‘women’s studies [josei gaku]’ have abruptly grown in popularity, and so, too, in Japanese contemporary art circles, there has been a movement to entrust (or to want to entrust) the new era of contemporary art to someone or something connected to the works of this strand of young ‘women artists’ [emphasis original]”.4 She goes on to note that, in M. Yoshizawa’s attitude, which is negative toward being pigeon-holed as a “girl” but not overtly vocal about it, she sees the potential of the new generation. F. Araki, who went on to become a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki, later reflected on that period during a 2007 solo exhibition of M. Yoshizawa’s work, noting that she “felt the project of women reporting on women had a dubious connotation, like something out of a weekly magazine”. At the same time, she expressed her faith in the artist, who had continued to produce life-sized works and “thoroughly explore only that which is realistically experienced in her daily life” without getting mired in the currents of commentary and mass media.5

Installation view, Selection from the CCMA Collection Special Edition: Yoshizawa Mika, Chiba City Museum of Art, ©Yoshizawa Mika, Photo by Kato Ken

Returning to the special issue itself, after the artist introductions and atelier visit articles, there follows an eight-page dialogue between creative director Ryōichi Enomoto and English literature scholar Kazuko Matsuoka, entitled “The Women Who Run Now [Ima kakeru onna]”. At that time, R. Enomoto was a producer of a cross-section of media types, including art, magazines, and theatre. K. Matsuoka was a translator and critic, and in later years, she became known for her translation of the complete works of William Shakespeare. In this conversation, K. Matsuoka discusses the art trends of the period, noting, “Nowadays, even male artists are steadily taking up cloth and cardboard, which were not originally used as art materials but for daily purposes, and using them to make things”.6

Indeed, in a reaction to the minimalist and conceptualist trends of the 1970s, the 1980s was a period of painting and sculpture revival, while at the same time—as R. Enomoto points out—various commodities were used as art materials against the backdrop of a mass consumption society. K. Matsuoka’s analysis of this situation is of particular interest here, as she comments, “This conflicted with women’s intensely concretist sensibilities, with their tendency to be unsatisfied unless they could touch something with their own hands”.7 If you look at the works by the artists featured in the special issue, almost all of them are made through the free modification and combination of a wide variety of materials, including cloth, paper, planks, driftwood, cardboard, vinyl, plastic, polystyrene, clay, metal, fur, leather, and tiles.

If we were to take one more thing from this conversation, it should be that the overwhelming majority of these women’s means of expression were in the form of installations, a medium that is not completed on a flat surface but takes up entire exhibition spaces. Installation art did not originate in this period, nor was it a trend seen only among women artists, but it is worth noting that so many women developed their own modes of expression within the comparatively new genre of installation art, which, unlike painting or sculpture, lacks an established tradition. As Barbara London, who organised an exhibition on Chie Matsui (1960-), another artist featured in this special issue, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, has noted:

Women artists find installation especially attractive. It’s contemporary; no fossilised tradition sets its boundaries. No hierarchy, male or otherwise, dictates the rules of installation. Artists are free to use whatever materials they wish, including domestic items typically associated with a woman’s place in society.8

This point seems to apply not just to C. Matsui, but to many of the women artists who were active in the ’80s. These women have no hesitation using materials typically described as “feminine”, which women of the previous generation might well have avoided, and realise their own modes of expression through the relatively new technique of installation. In her dialogue with R. Enomoto, K. Matsuoka comments, “One of the new levels of today’s feminism is the brazen presentation of womanhood. This is precisely the ‘what’s wrong with being a woman’ stance, and it came about in a very honest manner”.9 In general, we could say that the third wave of feminism, which occurred during the late ’80s and early ’90s, was already rushing to the forefront at this time.

Shōko Maemoto, Ōguren [The Big Red Lotus], 1986, mixed media, 230 × 650 × 73 cm, © Kobayashi Gallery

On the other hand, R. Enomoto describes the production style of these women artists as being in a state of transition, predicting that, “If we are not prepared to unflinchingly support the actions of such people, they will lose heart and gradually disappear, and, in the end, after a short span, we’ll all say to ourselves, ‘Goodness, there was a time like that, wasn’t there?’”10 Indeed, as far as my own Internet research could reveal, of the thirty-nine women artists introduced in the special issue, it is impossible in roughly half of the cases to confirm whether or not they continued their artistic activities. But because these artists may have chosen non-artist jobs, gotten married and started a family, or had various individual circumstances to contend with, we cannot really evaluate the pros and cons of their choices on the basis of simple percentages. Nevertheless, one cannot deny that, when it comes to recognition, those women who have continued their artistic activities have fallen well behind their male counterparts who emerged alongside them in the 1980s. It is only in the last few years, as the ’80s have become more and more historicised, that people have once more developed an interest in the works of the women artists who have energetically continued to produce them: including M. Yoshizawa, who has continued to exhibit at museums and art galleries while teaching university classes; Shōko Maemoto (1957-), who has recently resumed activities following a fifteen-year gap; and Tomoko Ushijima (1958-), who left Tokyo to pursue artistic activities in her hometown and has, in recent years, staged a series of solo exhibitions at various museums in Fukuoka.

Tomoko Ushijima, Installation view of the exhibition Double helix is not entangled, Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, 2022, © Tomoko Ushijima, Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, Photo by Satoshi Nagano

Moving beyond the 1980s, it is imperative, particularly with regard to postmodern art, to reflect back on the past and connect it to contemporaneous and future research and evaluations, while consistently maintaining a perspective on who has recognised what, and how they have done so.

The final component of the “Ultra Girls” special issue is a six-page text by the philosopher and poet Motoaki Shinohara—then a lecturer at the Osaka University of the Arts and subsequently a professor at Kyoto University and curator at the Takamatsu Art Museum—entitled “The Personal Universe of the Ultra Girls [Chō-shōjo shinpen uchū]”. In the works of these artists, M. Shinohara finds a partiality for the personal and for things familiar to them all: themes of home and family, use of handicrafts like sewing, exploration of the female body, and utilisation of motifs such as clothing. While he offers a careful analysis of their diverse modes of expression, it is always tied to femininity, and within the interstices of this analysis we catch glimpses of the illusions about women that M. Shinohara holds as a man. It is unfortunate that this text, which is the only discursive piece in the special issue, develops an artist theory that is excessively tied to notions of “the feminine”. To begin with, neither the approach of using commodities as artistic material, as R. Enomoto described, nor the attitude being partial to familiar objects, as M. Shinohara noted, is limited to women.

In her 1989 book Shōjo Folklore [Shōjo minzoku gaku], Eiji Ōtsuka refers to Japanese people who cease producing “things” within modern society and only consume them as girls [shōjo].11 E. Ōtsuka notes that many people, regardless of age or gender, developed an inner girl during Japan’s period of rapid economic development and bubble economy. That being the case, we can interpret an “ultra girl” as a subject who has gone beyond being a “girl” who only consumes to become someone who produces. In this interpretation, perhaps artists like Kazuhiko Hibino (1958-), who took the world by storm by turning products emblematic of mass consumption society into cardboard works, and Shinrō Ōtake (1955-), who created works by combining scrap materials with images from magazines and advertisements, ought to have been included in the special issue. In any event, while many of the works of these artists are now in museum collections or the subject of large-scale solo exhibitions, the job of placing women artists within the genealogy of Japanese art is still underway.

Norio Ōhashi, “Henshū kōki (Editorial postscript)”, Bijutsu Techo 38, no. 566 (August 1986): p. 248.

2

Editorial category of manga (Japanese comic), sometimes considered a genre, targeting an audience of young adolescent females and young adult women.

3

“Tokushū: Bijutsu no chō-shōjotachi [Special issue: the ultra girls of art]”, Bijutsu techō 38, no. 566 (August 1986): p. 19.

4

Fusako Araki, “Yoshizawa Mika: Kokochiyoi o motomeru (Mika Yoshizawa: seeking comfort)”, Bijutsu techō 38, no. 566 (August 1986): p. 80.

5

Fusako Araki, “Yoshikawa Mika wa daijōbu [Mika Yoshizawa is alright]”, Yoshizawa Mika 1990–2007 kaiga no hakken (Tokyo: Gallery Art Unlimited, 2007).

6

Ryōichi Enomoto and Kazuko Matsuoka, “Ima kakeru onna [The women who run now]”, Bijutsu techō 38, no. 566 (August 1986): 47.

7

Enomoto and Matsuoka, “Ima kakeru onna”, p. 50.

8

Barbara London, projects 57: bul lee/chie matsui (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1997). Hosted on barbaralondon.net, accessed May 30, 2023, https://www.barbaralondon.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/1997-Bul-Lee_Chie-Matsue-Projects_catalog-1.pdf.

9

Enomoto and Matsuoka, “Ima kakeru onna”, p. 59.

10

Enomoto and Matsuoka, “Ima kakeru onna”, p. 58.

11

Eiji Ōtsuka, Shōjo minzoku gaku [Shōjo folklore] (Tokyo: Kōbunsha, 1989).

12

Eiji Ōtsuka, Shōjo minzoku gaku [Le folklore shōjo], Tokyo, Kōbunsha, 1989.

Yukiko Yokoyama is a curator at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. She completed doctoral coursework in Interdisciplinary Cultural Studies at The University of Tokyo, followed by research in the history of art and representation at Université Paris Nanterre la Défense. Her curatorial positions include assistant curator at the Setagaya Art Museum (2009-2011); associate curator at The National Art Center, Tokyo (2013-2018); curator at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa (2018-2022). She specializes in Japanese and French modern art, and in recent years has been researching women painters of the Japanese modern era.

Yukiko Yokoyama, "What were “Ultra Girls”? Women Artists in 1980s Japan." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/qui-etaient-les-ultra-filles-cho-shojo-les-femmes-artistes-au-japon-dans-les-annees-1980/. Accessed 13 July 2025