Research

Installation view exhibition Roni Horn, De Pont Museum, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

In 1975 Roni Horn (born in 1955, in New York where she lives and works) made her first solo trip to Iceland. Many others would follow, Iceland becoming the place of initiation, apprenticeship and the discovery of forms and landscape.

It is where Horn feels she is able to “centre” herself and experience the fact of having an ever-changing identity. The set of eleven books to which she has given the generic title To Place comprises her photographs of Iceland’s landscapes and personal writings. Together they offer an account of the Iceland experience, which is in fact an experience of oneself through displacement and multiplication. The texts in the books are “inhabited” by literature, especially the poetry of Emily Dickinson. Horn’s work using the words of poets (among whom Wallace Stevens and William Blake) and writers (such as Flannery O’Connor, Clarice Lispector and Frank Kafka), and their relationship with plastic work, began with her first exhibitions in the early 1980s. The presence of Dickinson’s poetry in several of Roni Horn’s sculptural ensembles underscores another form of double, that of the importance of literature in the formation of her own formal language – which precedes the plastic and the visual.

Hack Wit – fool’s rainbow, 2014,watercolour, graphite, gum arabic on watercolour paper, cellophane tape, 61.6 × 39.4 cm. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. © Roni Horn – Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

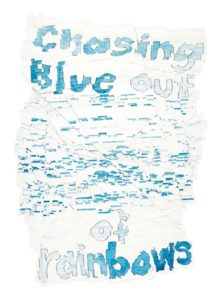

Hack Wit – chasing blue, 2014, watercolour, graphite, gum arabic on watercolour paper, cellophane tape, 61.6 × 43.8 cm. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. © Roni Horn – Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

In 2015, Roni Horn presented one of her most recent drawn series: Hack Wit (2013–14). These are watercolours that she elaborates using writing ink, gum Arabic and cellophane tape. Small in format compared with the Pigment Drawings she created in the mid-1980s, they are characterised by the lengthy process of the drying and the treatment of the pigments, the varnish and the paper, and by the actions of the cutting, cutting out and patient reorganisation of the drawings’ component materials. Pigment Drawings and Hack Wit have in common an economy of design, with the latter forming “sorts” of short visual poems in which words are made to stand out by their particular colour. The words are permanently distorted by the intersecting and parallel cuts of the paper that traverse them, as though their written form and grammatical sense had been shredded. The phrases are expressive, witticisms that laugh at, disrupt, subvert and wound their design in verbal delight while also defying the eye of the viewer/reader. The words form a composition of expressions which, at the conclusion of a complex and caustic process of permutation and reassembly, develop into a phrase that might be considered an aphorism or a haiku kneaded by changing plasticity, or as simple pleasure – both discontinuous and repeated – given by the text. These hack wits encompass both drawing and writing, thus an expression of a poetic image. The expression “hack wit” might be the meeting point of plasticism and language, creating a relationship of liaison and pairing. “Hack”, as in gash or cut, and “wit”, wordplay: the cutting of the drawing might be thought of as the “encounter”, and then, in a sort of plastic redundancy, as the doubling of the salient sense of the verbal poem. This form of doubling reveals the axial motif of the pair that is so dear to Roni Horn.

Installation view exhibition Roni Horn, De Pont museum, 2016: Hack Wit – dilemma butterfly , private collection ; Hack Wit – lucky water, 2014, private collection ; Hack Wit – bug suit, 2014, private collection ; Hack Wit – butterfly oblivion, 2014, private collection ; Hack Wit – airy dead, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The words in each Hack Wit are decided by Horn. Her characteristic writing is not unlike that of Emily Dickinson, who combined irony and wordplay with a personal form of punctuation that made use of dashes, small crosses and dots to give her poems a rhythm that is as much syntactical as it is visual. The words, therefore, are from the imagination of Horn, and not those of other artists, her literary “doubles”, who have appeared in her work since the earliest days and who will always stimulate her: Paul Valéry, Thoreau, James Fenimore Cooper, Rilke, Gide, Jules Verne, Simone Weil, William Blake, Franz Kafka, Wallace Stevens, Flannery O’Connor, Clarice Lispector, Poe, Joseph Conrad, Faulkner, Edith Wharton, Fernando Pessoa, Emily Dickinson…. The list of literary presences that underpin Horn’s work seems inexhaustible. They implicate the form of the plastic work, its metaphorical virtuality, and the experience of a new – three dimensional – appreciation of its configuration in an exhibition space. The linguistic and literary elements in Horn’s oeuvre precedes the plastic component (sculpture, drawing, photography), creating a double-natured coherence, in the sensory experience that it offers and communicates, and in the perception that it induces.

When Dickinson Shut her Eyes: no. 562 (Conjecturing a climate), 1993, 8 elements, solid cast black plastic and aluminium, variable lenghts (102.87 to 139.7 cm) × 5.08 × 5.08 cm, ed. of 3. Collezione Olgiati, Lugano. Courtesy Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano

When Dickinson Shut her Eyes: no. 562 (Conjecturing a climate), 1993, 8 elements, solid cast black plastic and aluminium, variable lenghts (102.87 to 139.7 cm) × 5.08 × 5.08 cm, ed. of 3. Collezione Olgiati, Lugano. Courtesy Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano

White Dickinson (Blossoms Have Their Leisures) , 2006, solid cast white plastic and aluminium, 145 × 5.08 × 5.08 cm, ed. of 3. Private collection, courtesy Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milano.

The Dickinson Works: forms of a literal empathy

Emily Dickinson is a pivotal figure for Roni Horn, while also a figure of empathy. Born in 1830 in New England, Dickinson wrote some 1800 poems. But she preferred not to publish them, lived as a recluse in her bedroom, and restricted her social life to her Homestead. Her involvement with the world occurred through the books in her father’s library and her abundant correspondence. American feminist criticism, which blossomed in the early 1990s, returned to the question of Dickinson’s poetry and the normative image of her as a “recluse”, reassessing her chosen solitude as a requirement for her creativity and the fundamental condition for her freedom. Roni Horn, who takes the stand of being “before gender”, “neutralises” Dickinson. As a figure with whom Horn identifies, the poet and her poetry are an integral part of Horn’s quest for a centre. Nor is it by chance that she read Dickinson’s poetry during one of her early trips to Iceland, the very place of the experience. Her reading of Dickinson was both a physical and intellectual immersion in the purely poetic, as well as an intimate relationship between the two. Horn’s experience of Dickinson’s poetry gave rise to what she calls her “Dickinson works”.

At the start of the 1990s, Horn produced four sculptural groups inspired by some forty poems and phrases taken from the poet’s correspondence, which she enclosed in a minimalist envelope made from two materials, aluminium and plastic: How Dickinson Stayed Home (1992–93); When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes (1993); Untitled (Gun) (1994), and Keys and Cues (1994–96). The later series, White Dickinsons, (2006–09) was composed exclusively of fragments of letters. With the exception of the installation How Dickinson Stayed Home – composed of 25 cubes made of aluminium and blue plastic arranged on the floor to create a phrase by Dickinson that defines her poetry, MY BUSINESS IS CIRCUMFERENCE – the other series comprise silky grey aluminium bars of different length inlaid with moulded plastic capital letters: black in When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes and Keys and Cues, and white for the series White Dickinson. In the manner of her presentation of the poet’s words, Roni Horn portrays Dickinson as the reclusive biographical figure for which she is known; in her sculpture she presents, in capitals, not just the poet’s words, but also a full verse (the Keys and Cues form the first verse of a poem), and a complete poem (in When Dickinson Shut Her Eyes). How might the inclusion by which these sculptures are characterised be described? Hospitality, welcome, partnership? Or, conversely, capture, appropriation, confinement, or reclusion of the poetic in a plastic form? It is very much a question of how Roni Horn “presents” Dickinson in the formal space of her sculpture and of the exhibition itself; and how she – Horn – places her – Dickinson – in her matter, her drawing. However, it is also important to see how Dickinson’s lyric verse, syntax, metaphoric power, and the visible and hidden meaning in her poems influence Horn’s choices. And how the sculptor offers the viewer/reader immediate access to the Dickinson experience, that of reading her poetry. In short, Horn presents the literary form of the poem in its literalness, presence and materiality, and in its poetical aspect as a normal “object” at home in the world. The Dickinson and Horn experiences make a pair and share the notion of empirical and sensorial knowledge. Dickinson/Horn form a literary and plastic partnership, with the sculptor placing the viewer at one of the points of the intimate geometry of her empathetic relationship and “posthumous collaboration” with the poet.

Installation view exhibition Roni Horn, De Pont Museum, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Installation view exhibition Roni Horn, De Pont Museum, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Literature as a flow of meaning in the art of Roni Horn

Roni Horn created an identical relationship with the American writer Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964) in her series of sculptures Her Eyes (1999–2005). In 2004 she presented Rings of Lispector (Agua Viva), an installation of words and phrases like a series of fragmented vortices on a khaki rubber-tiled floor, to create a new plastic composition of the book Agua Viva written by the Brazilian author Clarice Lispector (1920–1977). Hélène Cixous, another of Horn’s “collaborators”, of whom she produced superb photographic portraits, pointed out the “fusion” of the artist with book: “She [Horn] feels at home in lispectorian waters. “Reading” Clarice Lispector she feels that the I who speaks is sometimes Roni Horn”1. Water and writing – at the centre of a shared and reflected motif.

The liquid, androgynous and darkly reflective water of Roni Horn makes common poetic cause with a multitude of writers. It suffices to mention those with whom Horn dialogues in the text that she presents below the images in the photographic-lithographic series Still Water (The River Thames for Example) (1999–2000): the Charles Dickens of Our Mutual Friend, the Joseph Conrad of Heart of Darkness, the William Faulkner of The Wild Palms, and the Edgar Allan Poe of The Facts In the Case of M. Valdemar. Throughout this series, which reflects on the materiality and metamorphoses of water, the stories it tells and its identities, Horn quotes, refers to and questions literature: from Dickens’ sombre realism to Conrad’s metaphysical darkness, via the poetics of the double by Poe. This last author, of importance to Horn, is also present in the enormous circular sculptures made from a disconcerting, opaquely transparent cast glass, which she has produced since the 2000s. A remarkable set of ten recent pieces of different colour and geometric simplicity was presented last spring in the exhibition Roni Horn2 at the De Pont Museum in Tilburg (Netherlands). They stand there, a pure sensory experience for the eye and body. They are each accompanied by a title: a classic Untitled followed by a phrase of varying length in brackets. For example, Untitled (“I deeply perceive that the infinity of matter is no dream”). This quotation is taken from one of Poe’s novels, The Power of Words. The nine other sculptures are linked with such authors as Turgenev, Jean Rhys, V.S. Naipaul and Cormac McCarthy. The extracts are more than just quotations. They are freighted with Horn’s take on fear, cruelty, death, violence and sensuality, and are less narrative than metaphorical, a sense that is denied to the minimalist plastic forms. The literary doubles the sculpture, like the two faces of a changing mirror.

Marjorie Micucci is an art critic who is preparing a thesis on “L’inscription du texte et de la poétique d’Emily Dickinson dans l’œuvre plastique de l’artiste américaine Roni Horn” (Université Paris 7 Paris-Diderot).

Roni Horn, Rings of Lispector (Agua Viva) – with a text by Hélène Cixous, Hauser & Wirth Steidl, 2005.

2

Exhibition Roni Horn, De Pont Museum, Tilburg (Netherlands), 23 January–29 May 2016. Roni Horn will have an exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel from 2 October 2016 to 1 January 2017.

Marjorie Micucci, "Roni Horn and her literary doubles." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/roni-horn-doubles-litteraires/. Accessed 12 July 2025