Review

Ruth Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden, 2021-2022, view of the exhibition’s entrance, Herzliya Museum of Art, Herzliya, photo: Dor Even Chen

I met the Israeli artist Ruth Dorrit Yacoby (1952-2015) in the city of Arad, in the Negev desert, in the south of Israel. Here I founded an international residency program titled Arad Art and Architecture and the exhibition space Arad Contemporary Art Center, where I exhibited R. D. Yacoby’s work along with many other artists from Israel and abroad. In 2015 the Herzliya Museum of Art invited me to curate the first large-scale exhibition of R. D. Yacoby since her premature death. My personal acquaintance with the artist was key in curating Ruth Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden (25 December 2021-18 June 2022) (fig.1). The museum setting and its wide audience provided me with the ultimate conditions for a re-examination of R. D. Yacoby’s oeuvre.

Fig. 1 Ruth Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden, 2021-2022, view of the exhibition’s entrance, Herzliya Museum of Art, Herzliya, photo: Dor Even Chen

The main curatorial question was the disparity between R. D. Yacoby’s international acclaim and her involvement in the Israeli art discourse. For example, in the year 1996 alone, she held solo exhibitions of her work in China, Thailand, Singapore, Taiwan, Japan and Germany while a few years later in Israel, she was not even mentioned in A Century of Israeli Art, the most comprehensive reference book in thirty years on Israeli art.1 The exhibition explored how R. D. Yacoby’s approach to substantial issues of Israeli and Jewish societies such as birth, faith, spirituality, procreation, womanhood and motherhood were administered through her perspective as a Sephardic (North African Jewish roots) female artist, living in the periphery of Israel, and how this marginal positioning challenged the dominance of the Ashkenazi (European Jewish roots), Eurocentric perspective in Israeli culture and its concentration in the centre of Israel, mainly in Tel Aviv. The exhibition linked the patriarchal dominance of the female subject in regard to religious rituals and spirituality with the male-centred and westernised dominance of the Israeli art discourse. From its inception in the diaspora, long before the establishment of the State of Israel, the seeds of the Israeli art discourse were rooted in a westernised perspective on art and culture that recognised Ashkenazi male artists as its main protagonists. Dealing with the regimentation of the female body in a patriarchal society through life rituals associated with birth, death and burial, R. D. Yacoby’s artistic interrogations questioned the pre-eminence of the Ashkenazi and patriarchal perspective on art and culture that continues to control the Israeli art discourse up until today.

Fig.2 Ruth Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden, 2021-2022, view of the exhibition’s first section, Herzliya Museum of Art, Herzliya, photo: Dor Even Chen

I chose to open the exhibition with an in-depth exploration of representations of life rituals in R. D. Yacoby’s oeuvre, through a diverse range of iconologies from belief systems such as polytheism and monolatry (fig.2). The ten artworks in this section resonated with R. D. Yacoby’s interest in belief systems that have been present in the region since antiquity, many of which have lost their foothold in local historical narratives due to their obliteration by mainstream Ashkenazi Judaism.

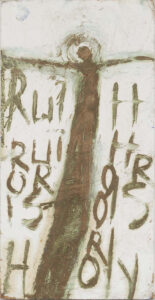

Fig. 3 Ruth Dorrit Yacoby, Ruth is Holy, 2008, paint, glue, ceramic, 180 x 160 cm, photo: Yigal Pardo © Courtesy Ruth Dorrit Yacoby’s Family

In the painting Ruth is Holy (2008) (fig. 3), a female silhouette appears in the background of a shallow box that is graced by vessels. The painting evokes ancient burial traditions in the region, in which the deceased were buried so that they could carry their goods into their afterlife. It demonstrates R. D. Yacoby’s liberated exploration of issues that are controlled in Israel by Jewish religious institutions. Dealing with mortality and the burial of the female human body, the artist brings to the surface the obscured issue of death and bereavement in Israeli society that has a quite varied history in the region.

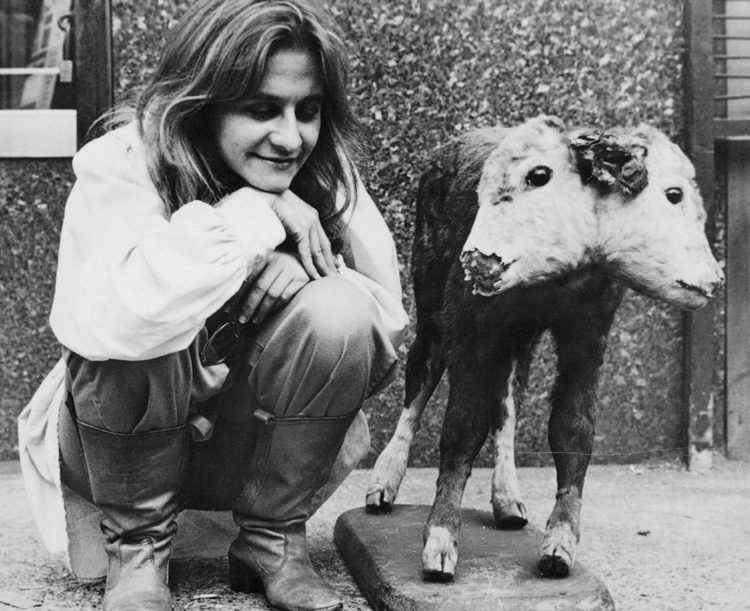

During my research I encountered a similar exploration of religious traditions in the artwork of Michal Na’aman (b. 1951), an Israeli woman artist from R. D. Yacoby’s generation. In her series A Kid in Its Mother’s Milk (1974) (fig. 4), M. Na’aman addresses the religious institutionalisation of female subjects by omitting the prohibition “do not” from the biblical phrase, “do not cook a kid in its mother’s milk”. A Kid in Its Mother’s Milk associates the Jewish tradition of separation of milk and meat with the painful separation at childbirth between a mother and her child. By disrupting the dietary context of the biblical phrase, M. Na’aman emphasises the religious institutionalisation of the female-newborn bond that retracts the natural protective shield of the mother’s milk from the newborn. The associations both artists make between feminism and religion are quite unique. It was rather uncommon, and still is today, for Israeli secular female artists to deal with religious Jewish issues through a feminist perspective. The overarching masculinity of the Zionist project and the military defence of Israel had ingrained a male-centred view in Israeli society dictating a religious and nationalistic discourse also in terms of art and culture.

Fig. 5 Ruth Dorrit Yacoby, Untitled, 2008, 24 x 47 cm, oil on formica, photo: Yigal Pardo © Courtesy Ruth Dorrit Yacoby’s Family

One of the most compelling themes of R. D. Yacoby’s oeuvre was situated in the heart of the exhibition. Nine artworks were organised around a watershed moment in the artist’s adult life, in which she reappropriated her birth name “Ruth” and inscribed her newly adopted name into many of her artworks (fig. 5). The theme presented how by reversing a moment in her childhood, when her mother changed her birth name from Ruth to Dorrit, the artist worked with her own identity as creative material. Adding her birth name “Ruth” to her adult identity, she created a feminine bond with biblical Ruth. According to the biblical narrative, after losing her husband, Ruth forms a female alliance with her husband’s mother and encounters pertinent questions of womanhood and motherhood in a patriarchal society. The artworks organised around the theme of “Ruth” highlighted the fact that the social constructs of womanhood and motherhood in the patriarchal Jewish society were a major concern for R. D. Yacoby, and her turn to female alliances as a source of strength of female subjects was consistent with the feminist reading of the biblical tale.

Fig. 6 Ruth Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden, 2021-2022, last section of the exhibition, Herzliya Museum of Art, Herzliya, photo: Dor Even Chen

I chose to dedicate the last section of the exhibition to exploring the repeated painted poems and broken sentences, words, phrases and syllables that R. D. Yacoby painted into her artwork (fig.6). Through this repetition, the artist inflicted a constant destabilisation of an accepted, consensual language. In the curatorial text, I associated the undermining of accepted linguistic structures in her text-based artworks with the work of Yona Wallach, an Israeli feminist poet who experimented with art, womanhood and Jewish mysticism in her poems through freely playing with language structures. Like R. D. Yacoby, Wallach also dealt with the very nature of feminine creativity within the social construction of a woman artist in Israeli society. But in contrast to Y. Wallach and Israeli artist Aviva Uri (1922-1989), who asserted that “If one wishes to create, one must firstly be an artist, and only then a woman”,2 R. D. Yacoby did not compromise motherhood for an art career. R. D. Yacoby’s liberal feminist approach encompassed the possibility of combining her female, gendered role with pursuing her career.

Fig. 7 Ruth Dorrit Yacoby, Untitled, 2010-2012, 120 x 180 cm, oil and fabric on wood, photo: Yigal Pardo © Courtesy Ruth Dorrit Yacoby’s Family

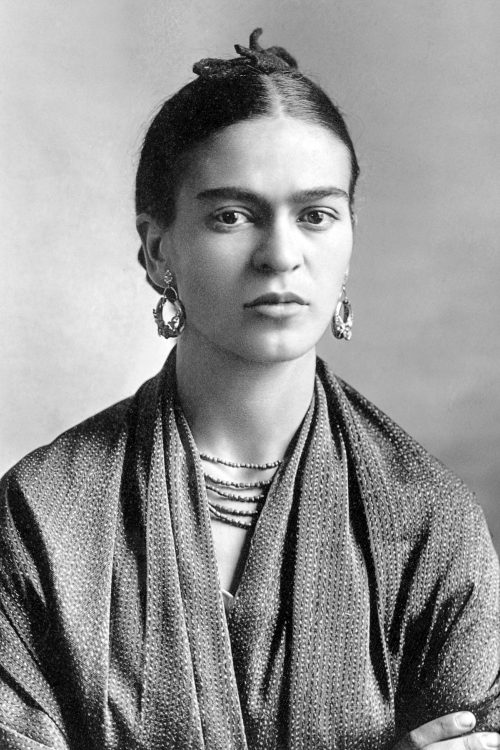

This approach is apparent in a series of text-based works in which R. D. Yacoby inscribed the names of female figures, such as the ancient Greek scientist Pythias who wrote, together with her husband Aristotle, an encyclopaedia of specimens of living things, and the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), who had an artistic relationship with her husband Diego Rivera (1886-1957) (fig.7). By dealing with female role models that combined their gendered role and their career, R. D. Yacoby expressed her liberal feminist approach in terms of her own existence as a wife, mother and artist.

In conclusion, R. D. Yacoby’s solo exhibition in Herzliya and her inclusion in a new installation of Israeli art curated by Dalit Matatyahu in the Israeli Art Department of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, represents a turning point in her reception in Israel. At a moment when it became popular to showcase forgotten or unfamiliar female artists in the context of mega-exhibitions on the international scene,3 the inclusion of R. D. Yacoby’s artwork in the context of one of the most significant exhibitions of Israeli art is well timed.

Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden drew a wide audience from central Israel, who came to be (re-)acquainted with the oeuvre of an Sephardic female artist from the Israeli periphery that fell between the cracks of local art discourse. Due to her radical inquiries into religiously restricted notions such as birth, bereavement, burial and pain, and her linking them with notions of womanhood, motherhood and care, the extensive exhibition touched on the reasons why despite her international acclaim, R. D. Yacoby’s oeuvre was obscured by the mainstream Israeli discourse that is constrained by a patriarchal, Ashkenazi perspective on Israeli art and culture.

Yigal Zalmona, A Century of Israeli Art (Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2013). Originally published in Hebrew by The Israel Museum in 2010.

2

Tal Dekel, “From First-Wave to Third-Wave Feminist Art in Israel: A Quantum Leap”, Israel Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring 2011): p. 154.

3

While Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden took place in Herzliya Museum of Art, the 59th Biennale, The Milk of Dreams, was held in Venice, curated by Cecilia Alemani. For the first time in its 127-year history, the biennale included a majority of women and gender non-conforming artists that reconsidered male artists’ centrality in art history and in contemporary art.

Hadas Kedar is an artist, curator and researcher in the field of curatorship. She is currently a doctoral candidate in a joint program of the University of Reading School of Art (UK) and the postgraduate program in curating at Zurich University of the Arts (Switzerland). Her research “Keeping the Edges Open: Towards an Inclusive Curatorial Practice in the Negev and Beyond” is based on the Negev desert and develops inclusive curatorial methodologies that integrate a wide range of cultural forms and diversify the curatorial agendas of Negev cultural institutions. Kedar lectures at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design and is a senior staff member at the Mandel Center for Leadership in the Negev.

An article produced in Partnership with Artis

Hadas Kedar, "Ruth Dorrit Yacoby: The Door to the Secret Garden." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/ruth-dorrit-yacoby-la-porte-vers-le-jardin-secret/. Accessed 7 March 2026