Research

Soun Gui Kim is a French artist, born in South Korea, who has lived in France since 1971. Born in 1946, a year after Japanese decolonisation, she attended a special primary school that valued extracurricular activities, founded by the UN on the rubble of a country devastated by the Korean War (1950-1953). Over the course of her studies, the young girl revealed her talent for painting and when her art teacher told her about Paris, “a city where the homeless and the painters live together”,1 she immediately saw herself as an artist working there. From then on, she began to train avidly, acquiring a knowledge of both artistic techniques and theory, and setting out to learn French before going to university. At the end of her master’s studies at Seoul National University, she became keen to break out of the two-dimensional framework in order to open up the visual field and give more space to temporality in her art. She made the most of an opportunity to secure an international scholarship offered by the French Ministry of Culture. S. G. Kim’s rebellious spirit led her to find Paris too conventional, so in 1971 she decided to stay at the Centre Artistique des Rencontres Internationales (currently known as the Villa Arson) in Nice as a guest artist. She quickly caught the attention of her fellow artists and professors. Critic Jacques Lepage discovered her outdoor installation Situation Plastique I, noting the affinities between her work and the productions of the group Supports/Surfaces, to which he then introduced her. She started to spend time with members of the avant-garde movement, particularly Claude Viallat (born 1936), Vincent Bioulès (born 1938), Patrick Saytour (born 1935), Jean-Pierre Pincemin (1944-2005) and Ben Vautier (born 1935). J. Lepage’s house became, according to her, “the heart of the Niçois avant-garde”. Encouraged by Alain Hiéronimus, the director of the École Nationale d’Art Décoratif in Nice, she passed a teacher’s degree and started teaching after only three years living in France. As an artist and teacher, she developed close intellectual relationships with some of her peers, such as C. Viallat, Christian Jaccard (born 1939) and Toni Grand (1935-2005), and experimented with new techniques.

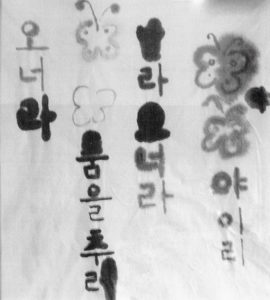

Soun Gui KIM, Forêt I, 1998-1999, pinhole, 180 x 120 cm and Forêt II, 1998-1999, pinhole, 180 x 120 cm, Courtesy to the artist

S. G. Kim’s work is mainly based on metaphysical thinking. A lover of philosophy, she studied Eastern classics in Korea, particularly the Taoist writings of Zhuangzi (c. fourth century BCE). The core concept of Taoism, non-action (wu wei) – that is, acting with natural spontaneity, free from any norm – later became a major theoretical focus in her art. Her pinhole works, such as Forêt I and II , now kept at the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou, and calligraphy works play on the collaboration between the contingencies of the actions of nature and those of the artist. According to Taoism, the natural realm is clouded by all that is artificial and therefore human (notions, ideas, language, etc.). S. G. Kim gave herself free rein to choose the mediums best adapted to her thinking, so as to break the codes that she felt were holding her back. This led her to exhibit in more experimental spaces, such as the J. & J. Donguy and Lara Vincy galleries in Paris.

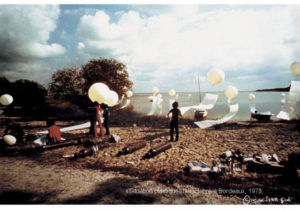

Video quickly became her preferred medium, which prompts the question of her link, as a Korean-born artist, to her fellow countryman Nam June Paik (1932-2006), who is considered a pioneer of the technique. But while N. J. Paik’s original approach to the television set mainly dealt with the manipulation of pictures on screen and the transcription of sound into visuals, S. G. Kim’s works were instead the result of her obsessional quest for a liberating medium or, to be more precise, an “empty vessel woven by time and light”.2 Following several attempts with photography and film, she was encouraged by her peers in the Niçois avant-garde to try her hand at video art and became acquainted with members of the group Signe (1971-1974) in Monaco. She created her first video work in 1973, using a camera she borrowed from the group: participants in the piece were invited to make kites and fly them. The process was simultaneously filmed and screened thanks to a monitor set up on site in which the event was held. In this case, the artist, the public, their surroundings, nature and the resulting visual work were all equal. She named this type of series Situation plastique II and III. In 1977 S. G. Kim met John Cage during a festival at the Sainte-Baume monastery, then, the following year, N. J. Paik at a performance at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. These encounters led to exchanges and collaborations between the three artists.3 As a teacher, S. G. Kim was convinced of the necessity to supply art schools with video equipment and to raise awareness of the then little-known medium among students. To this end, she persistently appealed to the French Ministry of Culture to implement a dedicated training course. After being awarded the first grant for this project, N. J. Paik invited her to New York, where she created the piece Bonjour Nam June Paik I (1982), a filmed conversation with the artist. She presented her fellow countryman’s work in France in the magazine Revue d’esthétique in 1983.4

Soun Gui KIM, Situation Plastique II – Manifestation Cerfs-volants, 1971-1973, video installation, super 8 mm film, Courtesy to the artist

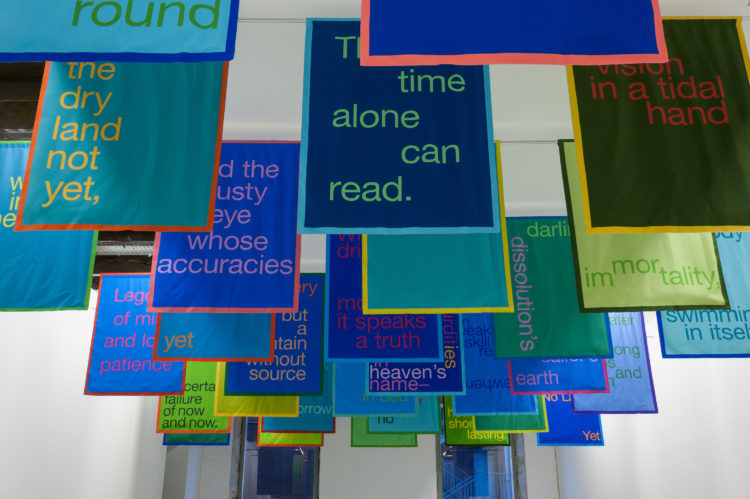

In addition to these artists, S. G. Kim most often kept the company of thinkers like Jacques Derrida, Jérôme Sans, Yves Michaud, Marc Froment Meurice, Jean-Michel Rabaté and Jean-Luc Nancy, with whom she was in regular contact and who wrote about her work several times. In France her passion for philosophy led her to take up studies in semiology and aesthetics, which in turn led her to take an interest in the analogies between Zhuangzi’s Taoism and the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Lectures and conversations also made up a large part of her activity. It was in fact during a round table at the Slought Foundation in Philadelphia in 2013, with Thierry de Duve and Jean-Michel Rabaté, that the artist and philosopher said that “one of the most important things about art is resistance”.5 However, she clarified that Taoist anarchism as a form of resistance is not meant to “negate otherness, but instead to listen to it and to make it happen, to finally be reborn in the thing; hence the absence of obstruction in interpretation”.6 Her mission as a creator was, therefore, in her eyes, to open up new paths.

Soun Gui KIM, Situation plastique III, 1973, installation, monocanal video (4:3), 16 mm film, 10 min 37 s, Courtesy to the artist

S. G. Kim never adhered to feminist movements, in line with her refusal to be confined to any specific domain. This includes her gender identity, which becomes irrelevant in the context of Taoism, which encourages a merging of the self with the world. While some women chose to join forces to improve their visibility and out of solidarity, others, such as S. G. Kim, worried that this would lead to a potential ghettoisation or victimisation and chose instead to seek recognition beyond their gender. For instance, S. G. Kim cites the example of a period of Korean history based on the coexistence of matriarchy and patriarchy, which she says is still embedded in the minds of Korean people, whose ancestors prior to the Confucian doctrine of the Joseon dynasty (1392-1897) enthroned several sovereign queens between the seventh and ninth centuries, giving rise to a more egalitarian culture. Moreover, the belated birth of the Republic of Korea systematically granted women the right to vote and work. When asked during a recent interview why she does not associate with feminist artists, S. G. Kim replied that she is a humanist rather than a feminist, if not an anarchist rather than a humanist.7

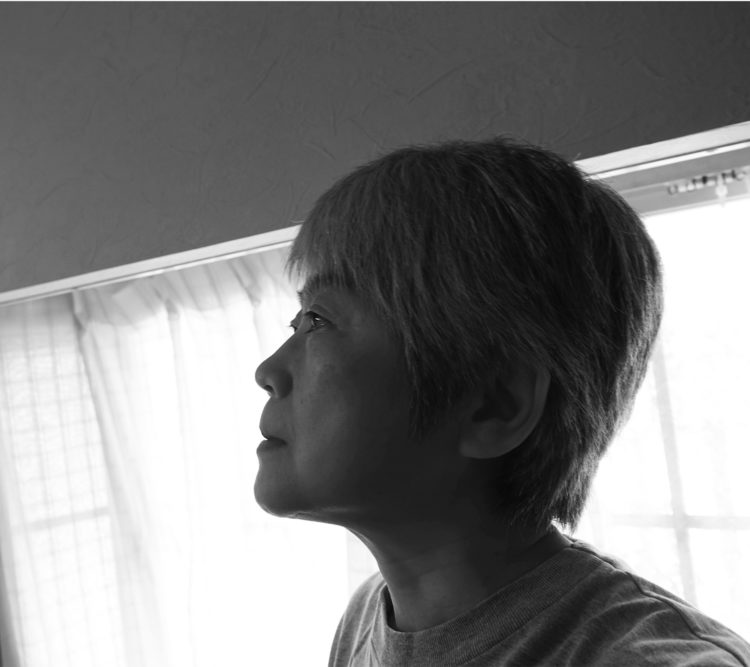

Soun Gui Kim with John Cage and Gérard Fremy at the festival Vidéo & Multimédia at la Vieille Charité, in Marseille, in 1986, Courtesy to the artist

The fact remains that S. G. Kim was indeed faced with gender-related obstacles. Despite Korea’s establishment of liberal democracy in 1948, the country still remains steeped in five hundred years of deeply Confucianist customs characterised by strict hierarchy and entrenched patriarchy. Few students move away from the traditional arts, and even fewer female students. When she decided to leave her country as a young woman, the artist faced strong opposition and physical violence from her family, who wanted her to marry after her studies. She also spoke of the difficulties she encountered in France: the persistent stereotypes associated with Asian women, the reluctance of dealers to work with a woman artist whose practice drew from philosophical theory, and the dearth of female teachers in art schools. S. G. Kim now admits that it took great strength of character as a woman to keep her independence without giving in to societal expectations.

Soun Gui KIM, Chemin de lumière, 1998, pinhole, analog C-print, 123 x 173 cm, Courtesy to the artist

It is easy to imagine how difficult it must have been for S. G. Kim to develop an artistic career as an Asian woman in a Western country. By proclaiming herself an anarchist, she not only refused to rely on any form of solidarity or sisterhood, but she also did not make compromises with her career. Nevertheless, France provided her with the opportunity for emancipation, shelter, and resistance. In fact, S. G. Kim was able to gain institutional support, and some of her works are now in high-profile collections, including the MNAM, the Maison Européenne de la Photographie and the FRAC Franche-Comté. Choosing to live in France and to work in the country as an artist was in itself an act of resistance for her, showing that her will is not to resist through the arts, but to prove that making art is, in and of itself, a form of resistance.8

All quotes from Soun Gui Kim are taken from interviews with the artist conducted in Paris from October 2021 to February 2022.

2

Rachel Heidenry, “Soun Gui Kim in Conversation with Cage, Derrida and Nancy”, artblog (17 December 2013).

3

Kim Soun Gui Studio, Bonjour Paik II, 7 October 2021 ; Kim Soun Gui Studio, John Cage, Empty Words – Mirage Verbal, 1986, 10 November 2019.

4

Soun Gui Kim, “Note sur Nam-June Paik / Temps et vidéo”, Revue d’esthétique, new series, no. 5 (1983).

5

Ibid.

6

Soun Gui Kim, “예술이란 의미가 아닌 의미의 곳인가 ?” [Is Art the place of meaning without signification ?], in 虛, 無, 靜에 대한 동양과 서양 사상의 비교 고찰, 성균관 유교문화연구소, 성균관 대학교, 서울 [Comparative Approaches to Emptiness, Nothingness, and Silence in the East & the West], Seoul, Institute of Confucian philosophy and culture, Sungkyunkwan University, 2016.

7

アンスティチュ・フランセ日本/アンスティチュ・フランセ東京 [French Institute in Japan/French institute of Tokyo], キム・スンギへのインタビュー―社会やアートにおける老女の表象 [Interview with Kim Sun Ki – The representation of an elderly woman in society and art], 29 May 2021 ; conversation with Soun Gui Kim, 28 October 2021.

8

Hara Ban, “ 나비처럼 날다 ‘작가 김순기’” [To fly like a butterfly, Kim Soon-Gi], Womennews, 13 December 2019.

Sujin Kim, "Soun Gui Kim, a Korean Artist in France: Art as a Form of Resistance." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/soun-gui-kim-une-artiste-coreenne-en-france-lart-comme-resistance/. Accessed 1 September 2024