Interviews

Portrait of Valeria Napoleone in front of: Lisa Yuskavage, True Blonde, 1998; Lily van der Stokker and Leo Kroll, Table and Chairs, 2004 © Photo Philip Sinden, collection Valeria Napoleone

An Italian based in New York and London, Valeria Napoleone was, in the late 1990s, one of the first collectors to commit to promoting women artists. Her collection, which includes nearly five hundred works, reflects above everything, a personal vision. Dedicated entirely to female artists of its own time, the collection is a unique panorama of contemporary production from the 1970s until today. From Ghada Amer to Lise Soskolne, alongside the likes of Martha Friedman, Judith Hopf, Lisa Yuskavage, Amanda Ross-Ho, Frances Stark, and Andrea Büttner, Valeria Napoleone collects singular works of art that question our era and our relationship with clichés, sexuality, economics, freedom and so on. Over the course of a rigorous journey as a collector and art patron, this fashionista, eccentric and creative, has built around her a whole “community” of women, of different ages and nationalities, whose varied practices coalesce around the values of courage and audacity, far from the art market’s rules.

Marion Vignal: You were one of the first to be interested in women artists and support them as a collector and patron. How did this come about?

Valeria Napoleone: I tend to say that I became a collector at the right place and the right time, New York in the 1990s, a period when this city abounded in artists. It was the epicentre of contemporary art. A significant number of women were drawing attention, like Cindy Sherman for example. At the time, I was just finishing journalism school and began to become interested in art. I came across a class at the New York Institute of Technology, where my sister was then studying. It was an art market training program, notably to become a gallerist. I enrolled and spent two years meeting amazing people, whether professors, artists or patrons. I discovered everything behind-the-scenes and understood what it meant to collect. There exists art lovers on one side, merchants on the other. At the time I was deeply impacted by a couple of passionate collectors who devoted all of their resources to their collection and privileged buying work over every other expense. If it came down to buying a new washing machine or acquiring a new work, for them the choice was clear: the machine can wait! That allowed me to better understand what type of collection I wanted to create. After two years I felt more mature, ready to defend a vision and values. I knew that this journey would occupy my whole life. I wanted to become a collector and not just a buyer. For me this meant committing to the long-term, acting with integrity, investing both time and energy.

Kathryn Andrews, Untitled (Clown Cabinet), 2011; Martha Friedman, Ladies Room, 2010; Jutta Koether, Allein! Allein!, 2006 © Photo Mariona Otero, collection Valeria Napoleone

MV: Was the choice of a collection entirely dedicated to women – and particularly to artists of your own time – one that came to you all at once?

VN: This decision came after two years of study, personal meetings and research. I realised that women artists were underrepresented, that their voices were not being heard despite being very active and productive. I did not understand how so many incredible talents and personalities were forgotten, discredited, whether in museums or art galleries.

MV: Was the subject of the status of women artists already rocking the art world?

VN: No, it was not even a subject. It was really me who was looking at these artists who were expressing themselves with another language, bringing new ideas. As a feminist, I believe in equal opportunities for all.

MV: How was your feminist commitment established?

VN: I was raised with the idea that as a girl and future woman I could do what I wanted with my life. What was important, in my family, was that I flourished, chasing after my dreams. My father played an important role in my life as a mentor. He had such esteem for my sister and me that we in turn absorbed. He always pushed us to explore our creativity. When I finished my art studies, it made me conclude that I was a feminist, when I had never asserted such previously, since I had not had to fight for my rights.

MV: What were the encounters and artists that impacted your beginnings as a collector?

VN: Ghada Amer was one of the women who changed my life. She has such courage, such integrity: she made an impression on me. I have long lived with her painting White #985, one of the first pieces to enter my collection, in 1997, and one of the first works in which she brought together the technique of dripping with embroidery. Ghada and I began our path together, her as an artist and me as a collector. I was one of the first to follow her. Afterward, we became friends. This work symbolises in some way the artistic journey that brings us together. The dialogue that I have established with her is very important to me. It has shaped my relationship with artists. My parents collected as well, but they were mainly interested in antiquities: those objects cannot talk!

Lisa Yuskavage, True Blonde, 1998; two Cassina stools by Charlotte Perriand © Photo Federike Helwig, collection Valeria Napoleone

MV: It seems that, more than anything, you have an interest in living beings and less in materiality …

VN: Yes, absolutely. And through my meeting young artists I discovered the importance of being part of a community of women. In creating my collection, I built this community and never dissociated my role as a patron from my status as a collector.

MV: For you, do those two necessarily go together?

VN: They are two sides of the same coin. I could not just be a collector. I need to meet artists, support their books, their catalogues, their personal exhibitions – everything is connected. These past few years, I have been very active in particular with Studio Voltaire in London, the Whitechapel Gallery, and institutions like the Association of Women in the Arts, or the New York University Global Council.

MV: How would you define this community?

VN: It is a rather varied group made up of people from different countries, cultures, generations, each animated by different causes. All of them have a certain energy in common. My collection is a personal journey. I lean toward artists who touch me, who make me discover new worlds. I admire conceptual artists very much, and those who have the courage to convey powerful messages. I am always looking to be surprised. This is one of the essential elements of my research. Lisa Yuskavage was one of the first artists who I discovered in the late 1990s. I particularly like her approach towards nudity, her incredible talent for painting. There is always a certain audacity in her painting, a singular attention to detail; these speak to me. I equally adore the work of Margherita Manzelli, whom I met in the very early days of my collection. She is, in my opinion, one of the best painters of her generation. Her paintings are extensions of herself. She features herself in her paintings and always appears alone in the middle of a space, her gaze towards the viewer. Sometimes, in certain exhibitions, she stands beside her paintings, as in a performance.

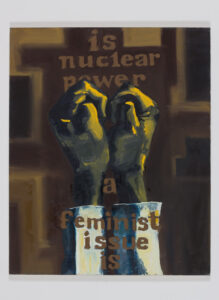

Lise Soskolne, A Feminist Issue Is, 2005 © collection Valeria Napoleone

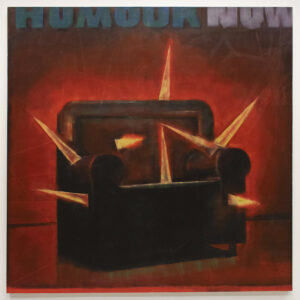

Lise Soskolne, Humour Now, 2005 © collection Valeria Napoleone

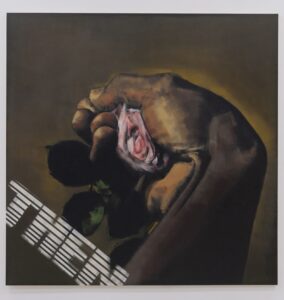

Lise Soskolne, Then, 2006 © collection Valeria Napoleone

MV: When you choose an artist’s work, to what are you paying the most attention?

VM: Over time I have learned to recognise the type of reaction that I need to have in front of a work. I experience a kind of agitation; something very emotional, physiological comes into play. If I begin to rationalise it, it no longer works. I have to have confidence in my eyes, in my feeling of seeing something that I have never seen before. Not long ago, I met a New York artist, Lise Soskolne, who is among the activists in the group W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy). This organisation seeks to establish sustainable economic ties between artists and institutions as well as to regulate the market. I saw her work and immediately fell in love with her images. Her work is so full of audacity, of strangeness. When I later met her, it was a tremendous surprise. Recently, I also met Julia Scher, an American artist living in Germany. She works around video surveillance and the theme of violation of privacy. These are both artists who deserve our full attention.

MV: Does this reaction in front of artworks also happen with artists whom you do not know personally or does it always happen by way of a prior meeting with someone?

VM: No, I often have such a reaction in front of a work by a creator whom I do not know. I do a lot of prior research on the artist and her work, I contact her gallery, I lean into her earlier pieces. It sometimes happens that six months or a year go by until I really grasp what drives the artist. These are among the essential parts of my research. Meeting is a bonus, a way of understanding the deeper motivations behind the work.

MV: Is the inclusion of a work or an artist in your collection akin to bringing in a new member of the family?

VM: Absolutely! When I began to collect, I said quite quickly that I was trying to amplify the voices of women who had been forgotten in art history. Each voice counts. It is not difficult to find artists; harder is to find the major works and uphold expectations at their highest level. I am ready to wait a long time before acquiring a work. My choices are quite specific and it is crucial that each work that enters my collection has its relevance. It is never a random choice, but always the result of reflection around a key work in an artist’s career.

MV: Do you ever part with works?

VM: No, I do not resell. I am convinced that I am creating something that has a logic and each piece in my collection has its own importance.

MV: Do you intend to give another life to your collection, whether by way of a publication, an exhibition, or even a foundation?

VM: Yes, that is under consideration. I am in the middle of working to create a space in Milan that will be a private residence but also be accessible by appointment. For now I support museums and other organisations; my collection continues to develop at my homes in London and New York.

MV: How does your family handle the fact of living daily amongst so many works by present-day women?

VM: I push many limits. My children were raised surrounded by contemporary art and among works that are often heavy, sometimes even unsettling. For me this collection has an educational value. Certain subjects make reference to major social themes: sexuality, gender, the fact of being different and so on. For example in London we live with a mural by Lily van der Stokker that includes the words “100% Stupid”. This work evokes the gaze of others insofar as it imposes their judgement – this question of the “evaluation” of intelligence is familiar to me: my daughter having Trisomy 21. Lily van der Stokker challenges the system. She became known after having spent many years in the shadows. When I met her in New York, she was represented by a small gallery. Her work is quite radical. She speaks notably of daily life, old age, discomfort and the conflict between ugliness and beauty.

MV: Since you began collecting the work of women artists, do you have the impression that things have evolved in terms of their visibility or renown?

VM: It’s complicated. Previously, women artists were the big blank in museums, they had but very little support. Now, things are changing, but it takes decades. Today there is a lot of attention and speculation on young artists; by contrast, women artists who are 50 years old, hence having a 30-year career and a substantial body of work, are neglected, even when they often have considerable importance. I am above all interested in artists who no one expects, who are not followed. I often go to artists’ studios. I am building my collection for posterity, for later generations, not for contemporary art fairs or catalogues. I have been helped by friends who are artists, curators and gallerists, including Barbara Weiss in Berlin, the galleries Hollybush Gardens and Greengrassi in London, and Kaufmann Repetto in Milan.

From the left: Gaetano Pesce, armchair Gli Amici (The Friends), 2009; Andrea Buttner, Nativity, 2007; Nathalie du Pasquier, Totem, 2018 © Photo Katie Lock collection Valeria Napoleone

MV: Among the artists to whom you are close, there is Andrea Büttner. What place does she occupy in your collection?

VM: I discovered Andrea Büttner at the very beginning of my journey. She is a deeply conceptual artist whom I adore and has since become a friend. She explores in particular the question of humility, of our relationship to identity, religion and tradition. Her triptych Nativity, made in 2007, is among the highlights of my collection. I discovered her work at the Whitechapel Gallery as part of the jury for the Max Mara Art Prize. Andrea was one of the artists nominated and she won. It was a huge step in her career. Her work is at once very poetic and powerful.

From the left: Kathryn Andrews, Untitled (Clown Cabinet), 2011; Frances Stark, The Inchoate Incarnate: After a Drawing, toward an Opera, but Before a Libretto Even Exists, 2009; Amanda Ross Ho, Vertical Dropcloth Quilt (Jack in the Pulpit), 2012 © Photo Mariona Otero, collection Valeria Napoleone

MV: You also have a striking piece by Frances Stark, Telephone Dress; where did this piece come from?

VM: I have been following the work of Frances Stark for many years. This dress is a piece that she wore during one of her performances at Performa 11, New York’s performance biennial. Frances Stark is also an author who turns a critical gaze towards the system of the art market. Her body of work is very irreverent; I really love it.

Valeria Napoleone in front of Nina Canell, Falke Pissano and Berta Fischer © Photo Philip Sinden, collection Valeria Napoleone

MV: What does it mean for you to live day-to-day with all of these pieces?

VM: They open the mind and reveal new perspectives. They push you to look at life from another point of view. All of these women follow their convictions without compromise. They do not have any other choice but to be strong and courageous. To support this type of talent gives me incredible joy and energy. I am, in a certain way, implicated with them in this search, this truth, this undertaking. To live surrounded by their works reminds me that we do not have any other choice than to move forward. It is fortunate to be able to participate in this journey.

Marion Vignal is a curator, consultant and author. An expert in design and contemporary art, she supports young international artists through exhibitions, commissions and special projects. A literature and art history graduate, she has written several books on the history of design, interior design and olfactory art. She is president of ida M., an editorial and artistic consultancy she set up in Paris in 2015. In 2021 she initiated the experiential exhibition programme Genius Loci, which aims to spark dialogue between architectural heritage and contemporary art.

Marion Vignal; Valeria Napoleone, "Valeria Napoleone: Collecting Community." In , . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/valeria-napoleone-collectionner-au-feminin-pluriel/. Accessed 14 February 2026