Cindy Sherman

Krauss Rosalind E., Cindy Sherman: 1975-1993, New York, Rizzoli, 1993

→Burton Johanna & Owens Craig, Cindy Sherman, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2006

Cindy Sherman, Kunsthalle Basel, Basel, 28 March – 20 May 1991 ; Staatsgalerie moderner Kunst, Munich, 21 June – 24 July 1991 ; Whitechapel gallery, London, 2 August – 22 September 1991

→Cindy Sherman, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 16 May – 3 September 2006 ; Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz, 25 November 2006 – 14 January 2007 ; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlenæk, 9 February – 13 May 2007, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, 15 June – 10 September 2007

→Cindy Sherman, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 26 February – 11 June 2012 ; Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, 14 July – 7 October 2012 ; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 10 November 2012 – 17 February 2013 ; Museum of Art, Dallas, 17 March – 9 June 2013

American visual artist.

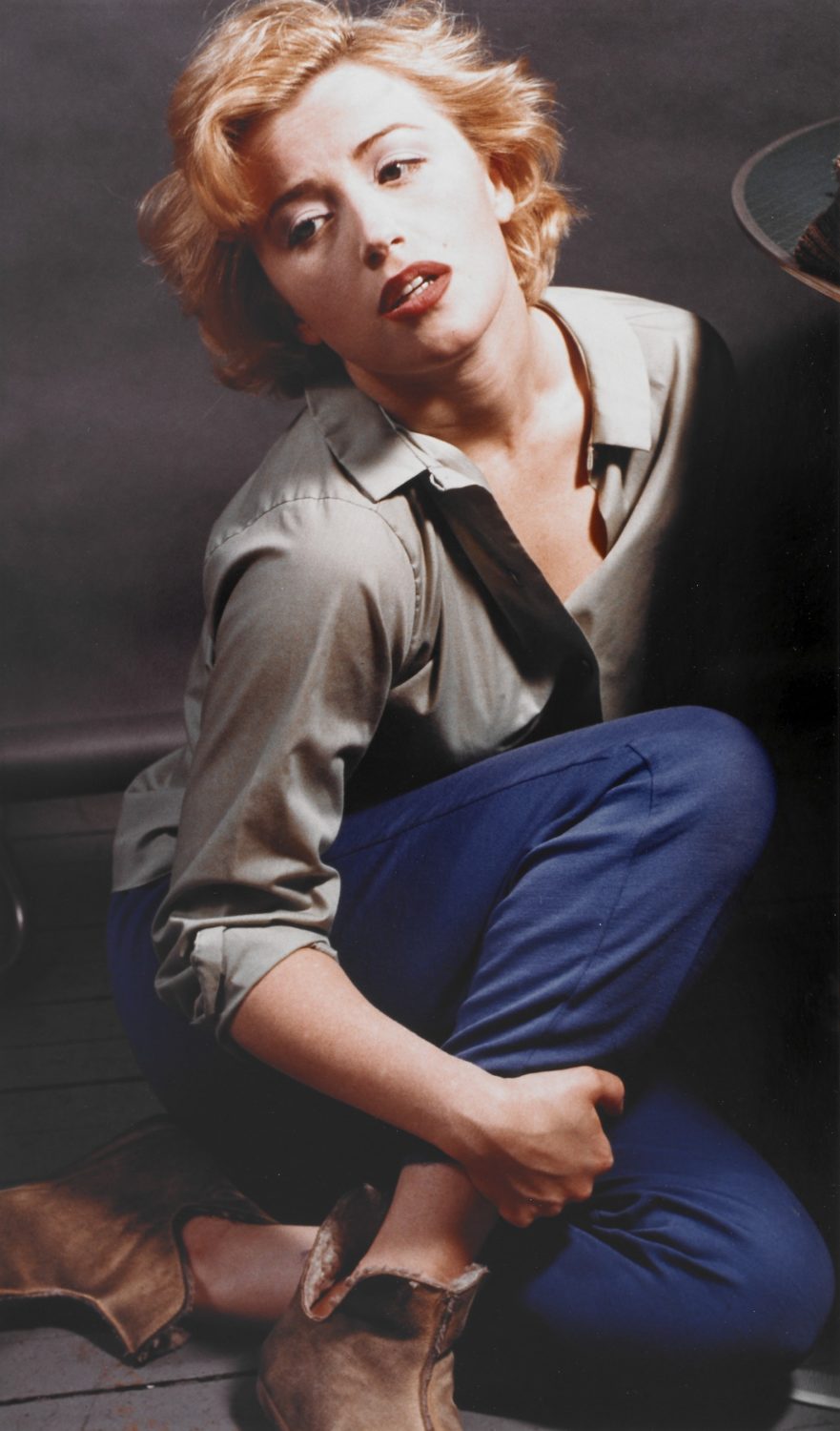

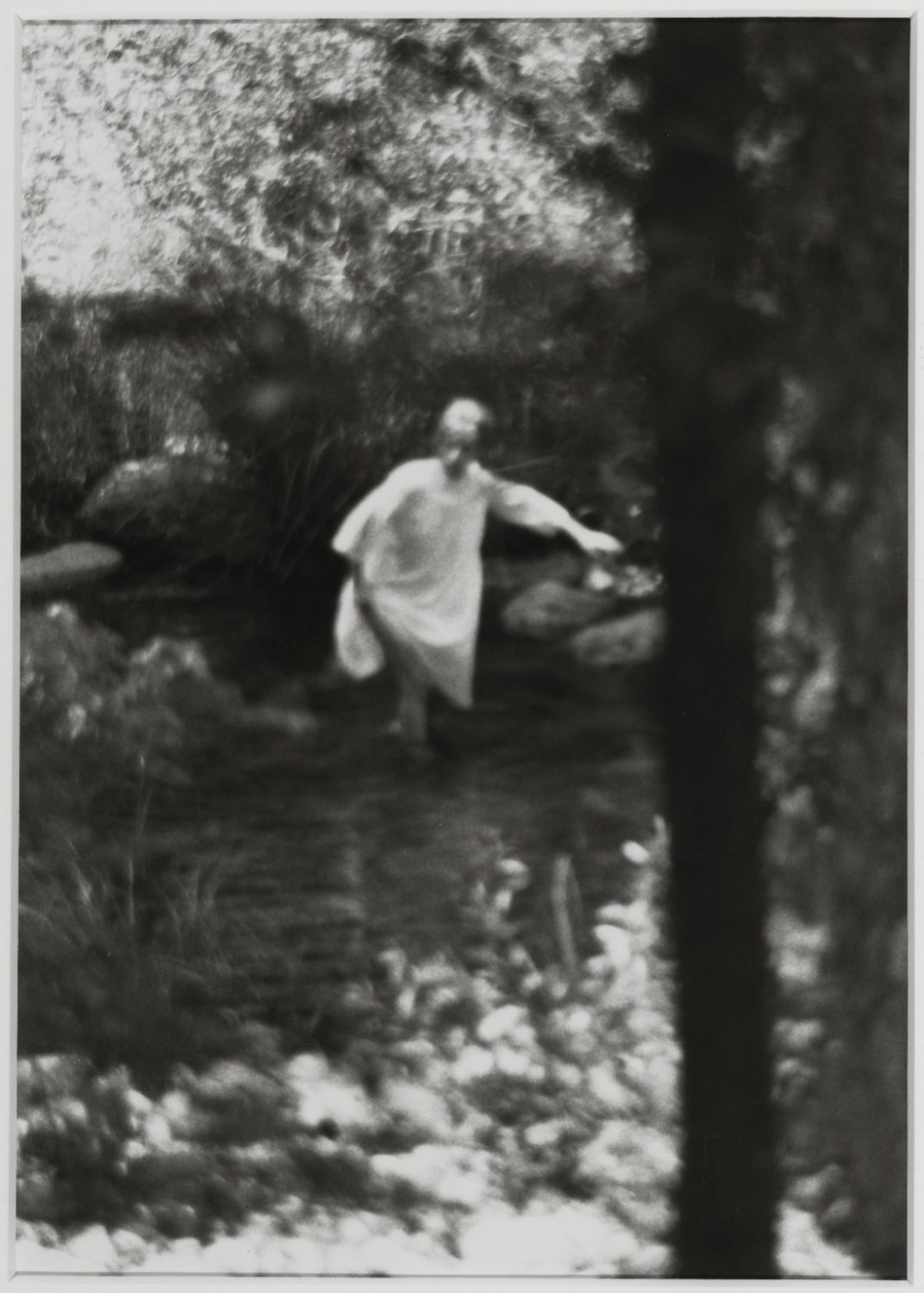

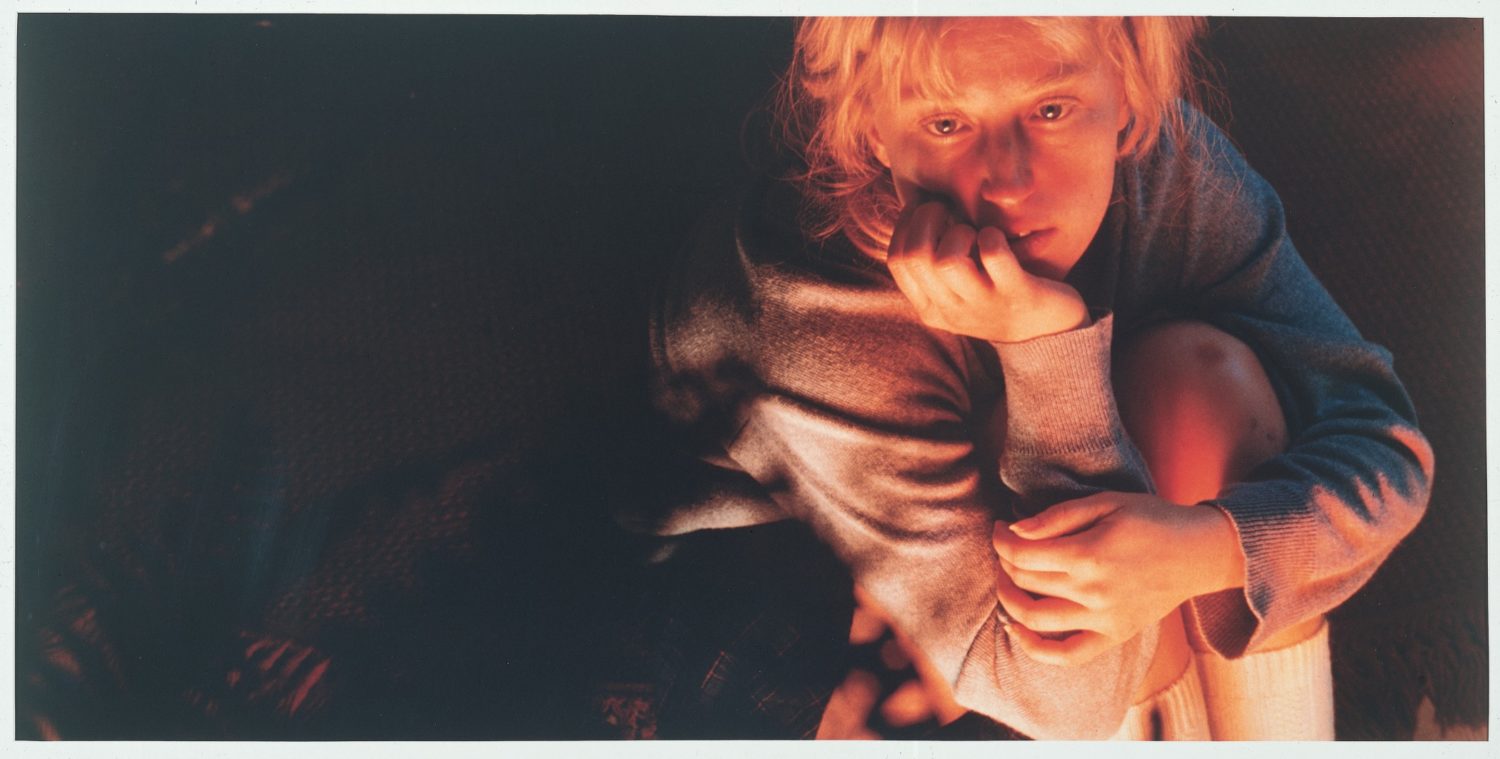

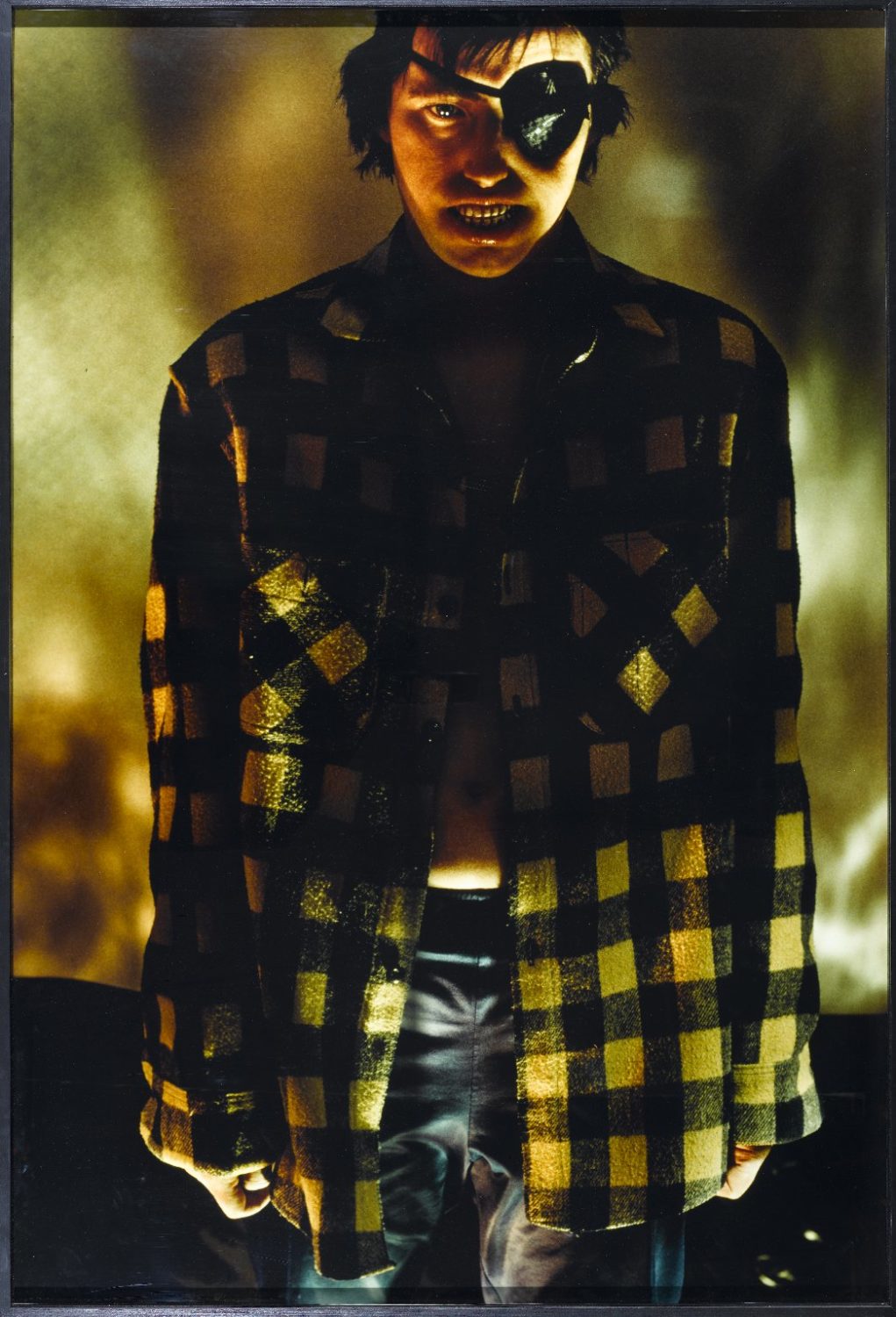

Ever since her famous series Untitled Film Stills (1976-1980), in which she staged herself posing as stereotypes found in film, painting, literature, and everyday life, Cindy Sherman has established the themes of dressing up, hijacking, and parody on the international photographic scene, of which she is now one of the leading figures. Before moving to New York in 1977, she studied photography at Buffalo State College, where she founded the independent exhibition space Hallwalls with Robert Longo and Charles Clough. She has always featured herself as a model, as far back as her first work (Untitled A-E, 1975), a series of five self-portraits in costume. Her imagery took a more contemporary turn when she began to use colour and large formats in her series Rear Screen Projections (1980) and Pink Robes (1982), following which she worked on more angst-ridden series, with crude wigs and prostheses meant to “be seen”. The series Fairy Tales (1985) turned fairy tales into nightmares, and her Horror and Surrealist Pictures (1994-1996) featured assemblages of bodies and monsters. Violence was exacerbated in the series Disasters (1986-1989), and became pornographic in her Sex Pictures (1992) and Broken Dolls (1999). Beyond the obvious subversion and irony, these series, similarly to the works of Hans Bellmer, staged contorted, dismembered and burnt dummies and mannequins as instruments of a macabre fantasy of the inanimate.

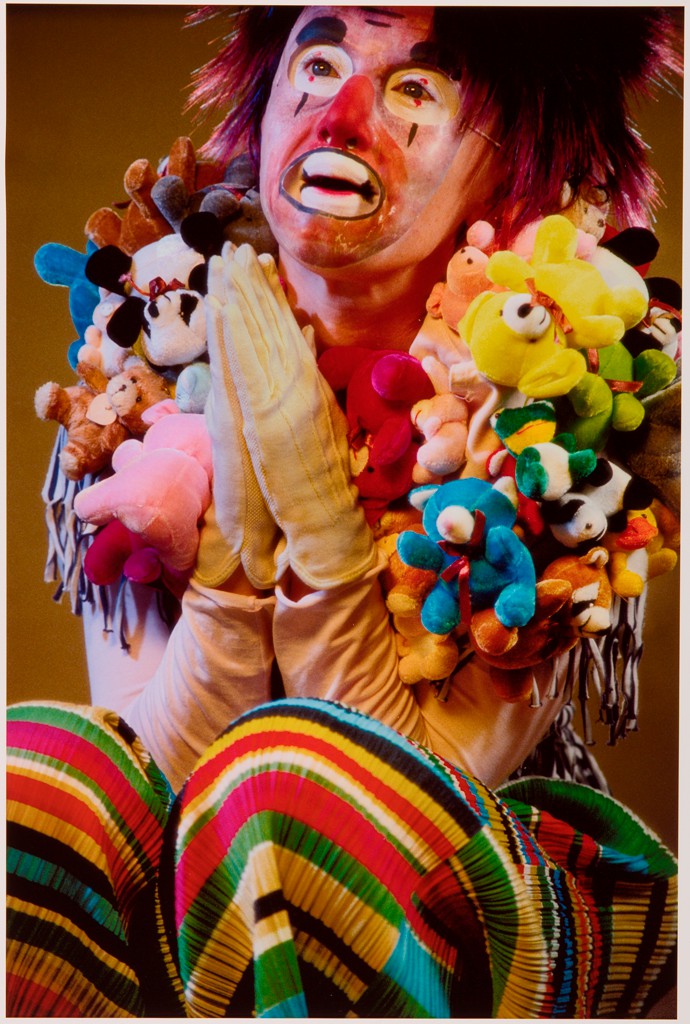

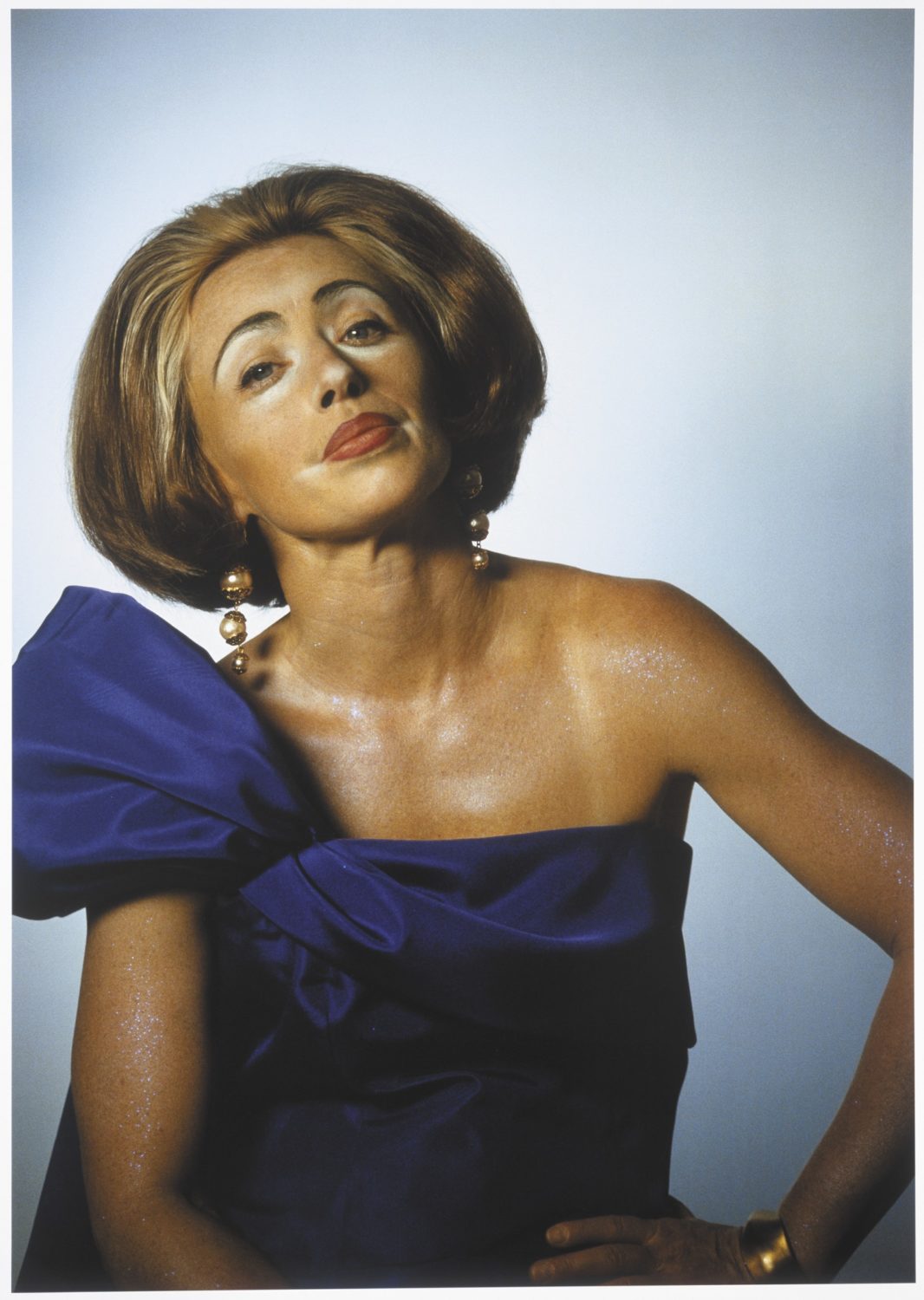

The commissioned works she created for fashion brands in the 1990s also tended toward dehumanisation; the series History Portraits/Old Masters (1988-1990) is a dark take on art history that sees the artist dressed up as portraits by the old masters, with prosthetic noses, breasts, and garish colours exacerbating the artificiality of the scenes. It only made sense that C. Sherman would then choose to focus on the theme of masks (Masks series, 1994-1996) and clowns (Clowns series, 2003-2004). Her extreme approach to costume reveals the omnipresence of death and a fascination with ugliness that borders on terror. In contrast to documentary photographers, C. Sherman is the major representative of a fictional tendency in contemporary photography, which thrives on the grotesque and comic (History Portraits) or on exuberant and dark theatricality (Fashion series 1983, 1984, 1993, and 1994). Her costumed self-portraits are revelatory of an identity crisis, particularly manifest in her series Hollywood/Hampton Types (2000-2002), in which she stages herself as forgotten, out-of-work actors. These face-on portraits, framed like official photographs, express aging and disillusionment, as well as the despair of being reduced to a single role.

C. Sherman is considered a feminist artist when she creates satiric portraits of herself to denounce the stereotypes encouraged by film, painting, and photography. Like Jo Spence, she deconstructs the way we see women and utilises a fictional approach in the re-appropriation of this image. She has, however, received criticism from some feminists for the indulgence with which she depicts female stereotypes and for the victimised position that most of her “characters” adopt. Nonetheless, her work also marks a return of the female body to the forefront, almost a reaction to theoretical feminism. As such, her Horror and Surrealist Pictures can be seen as reactions to the idealisation of women. C. Sherman sees photography as a weapon against “high art”, and her iconoclasm appears as a popular way of getting back at museums: “I wanted to make something that people could relate to without having to read a book about it beforehand”. Like Claude Cahun, she draws inspiration from popular myths and the popular imagination. For example, her Untitled Film Stills show to what great extent American cinema has influenced popular culture: her “multiples without originals” (Rosalind Krauss), without referents, and her allusions to a vague cinematic universe, make her a major representative of postmodernism. To her, photography is both an artistic and critical device: she uses it as a head-on denunciation of the triumph of television and the fashion industry, from which she was often commissioned work in the ’80s. But, unlike Jeff Wall, to whom she is sometimes compared, she chose not to develop a theoretical discourse, thus perpetuating the mystery surrounding her abundantly discussed work.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Under the Gaze: The Art of Cindy Sherman

Under the Gaze: The Art of Cindy Sherman