Seiko Kanno

Kato, Mizuho. “Seiko Kanno: Between Poetry, Painting, Music and…” In Kanno Seiko: Shi to kaiga to ongaku to… (Seiko Kanno: A Retrospective, Between Poetry, Painting, Music and… Exhibition Catalogue), pp. 6–16. Ashiya and Sendai: Kanno Seiko-ten Jikkōinkai (The Executive Committee on the Seiko Kanno Exhibition), 1997

→Wada, Koichi. “The Painting by Seiko Kanno: Balance the Intellectual Construction and the Artistic Sensibility.” In Kanno Seiko: Shi to kaiga to ongaku to… (Seiko Kanno: A Retrospective, Between Poetry, Painting, Music and… Exhibition Catalogue), pp. 102–104. Ashiya and Sendai: Kanno Seiko-ten Jikkōinkai (The Executive Committee on the Seiko Kanno Exhibition), 1997

→Wada, Koichi. “The Process of Making Seiko Kanno’s Painting The World of Lévi-Strauss III.” Miyagi-ken Bijutsukan kenkyū kiyō (The Bulletin of the Miyagi Museum of Art), March 19, 2021: pp. 102–110

Seiko Kanno: A Retrospective, Between Poetry, Painting, Music and…, The Ashiya City Museum of Art and History, Ashiya, Hyogo, Japan, April–May 1997

→Seiko Kanno: A Retrospective, Between Poetry, Painting, Music and…, The Miyagi Museum of Art, Sendai, Miyagi, Japan, February–March 1997

→Seiko Kanno Solo Exhibition, Gutai Pinacotheca, Osaka, Japan, November 1971

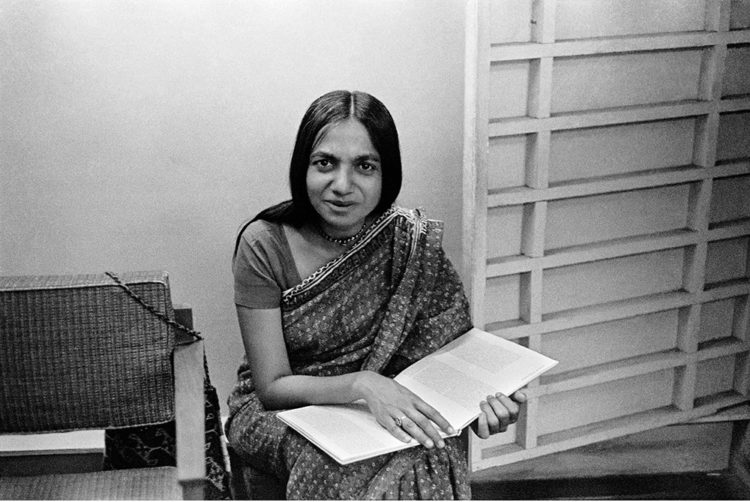

Japanese painter.

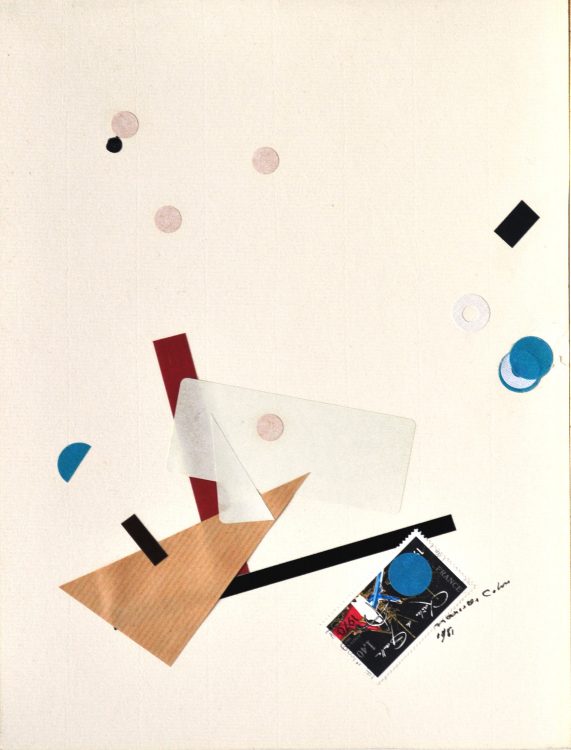

Born Seiko Aizawa in Sendai in 1933, Seiko Kanno took an interest in painting and composing poetry while in high school. After graduating from the Arts & Crafts Department of Fukushima University’s School of Human Development and Culture in 1956, she began painting lyrical abstract works using colour-field composition the following year and regularly exhibited her work at such venues as the Japan Watercolor Federation (Suisai Renmei) and the Sogenkai Exhibition. Towards the end of 1958, she moved to Kobe upon marrying Muneo Kanno and, alongside her painting output, came up with a method of tearing apart English-language newspapers to collage into art pieces while listening to Mozart. These works could be called transitional when considering S. Kanno’s later distinctive style, and yet they are noteworthy for their integration of creative expression with sensitivity to “sound.” In the spring of 1964, S. Kanno visited the Gutai Pinacotheca with artworks in hand to solicit advice from the leader of the Gutai Art Association (Gutai), Jirō Yoshihara (1905–1972). In September of that year, she exhibited her collages for the first time as a non-member at the Gutai New Works Exhibition. Having continued to write poetry since her school days, S. Kanno began publishing poetry, also in 1964, written in katakana and focused less on meaning than the resonance of sound.

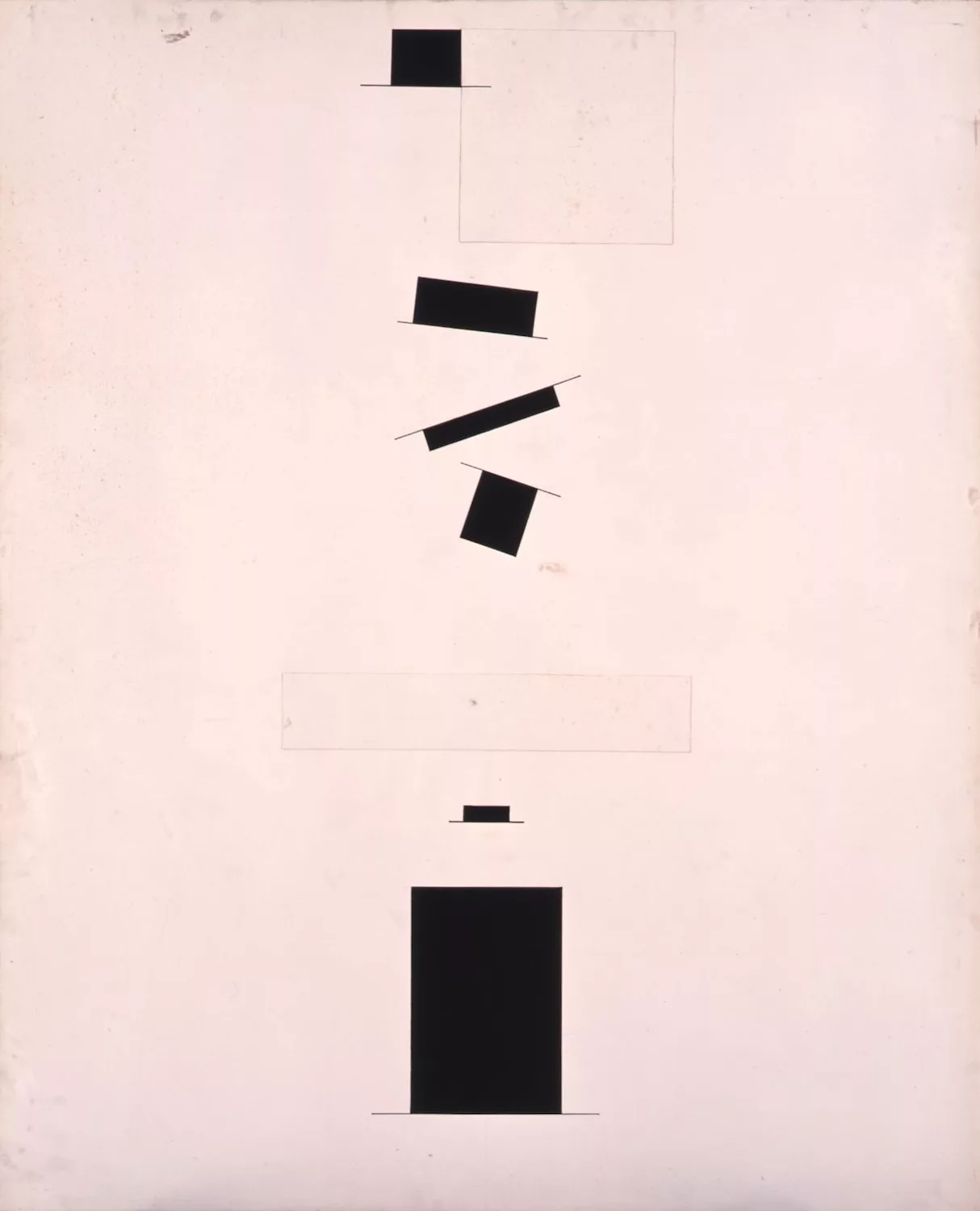

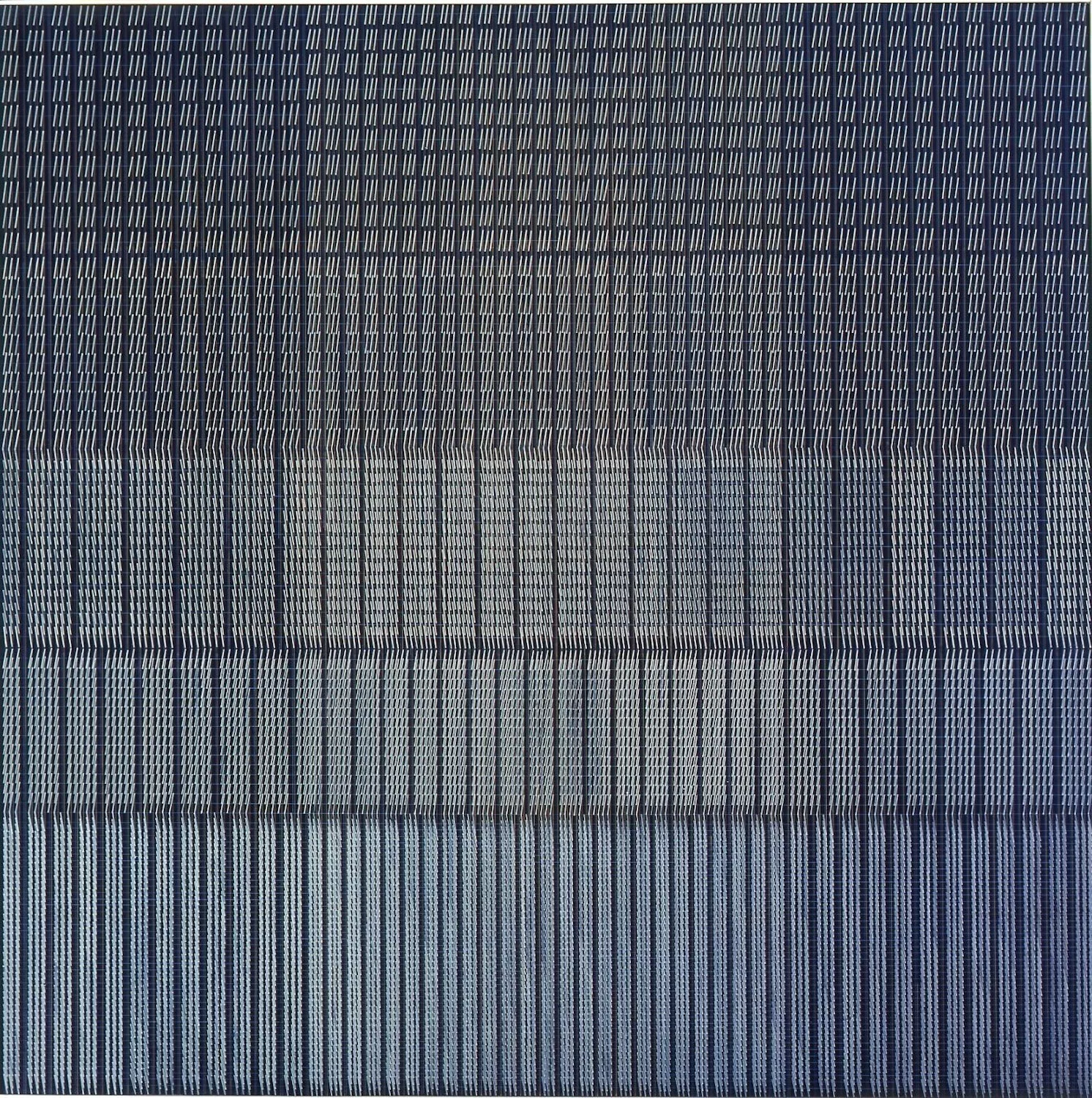

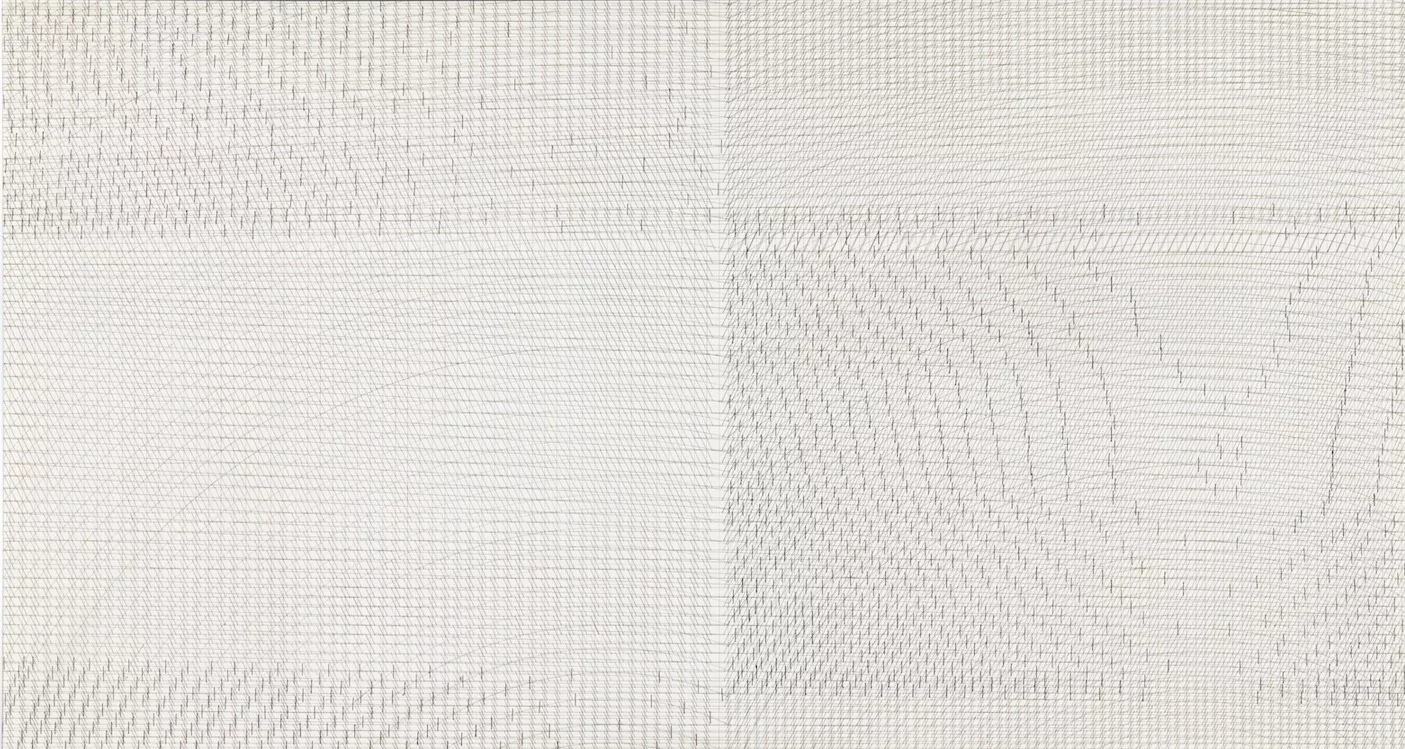

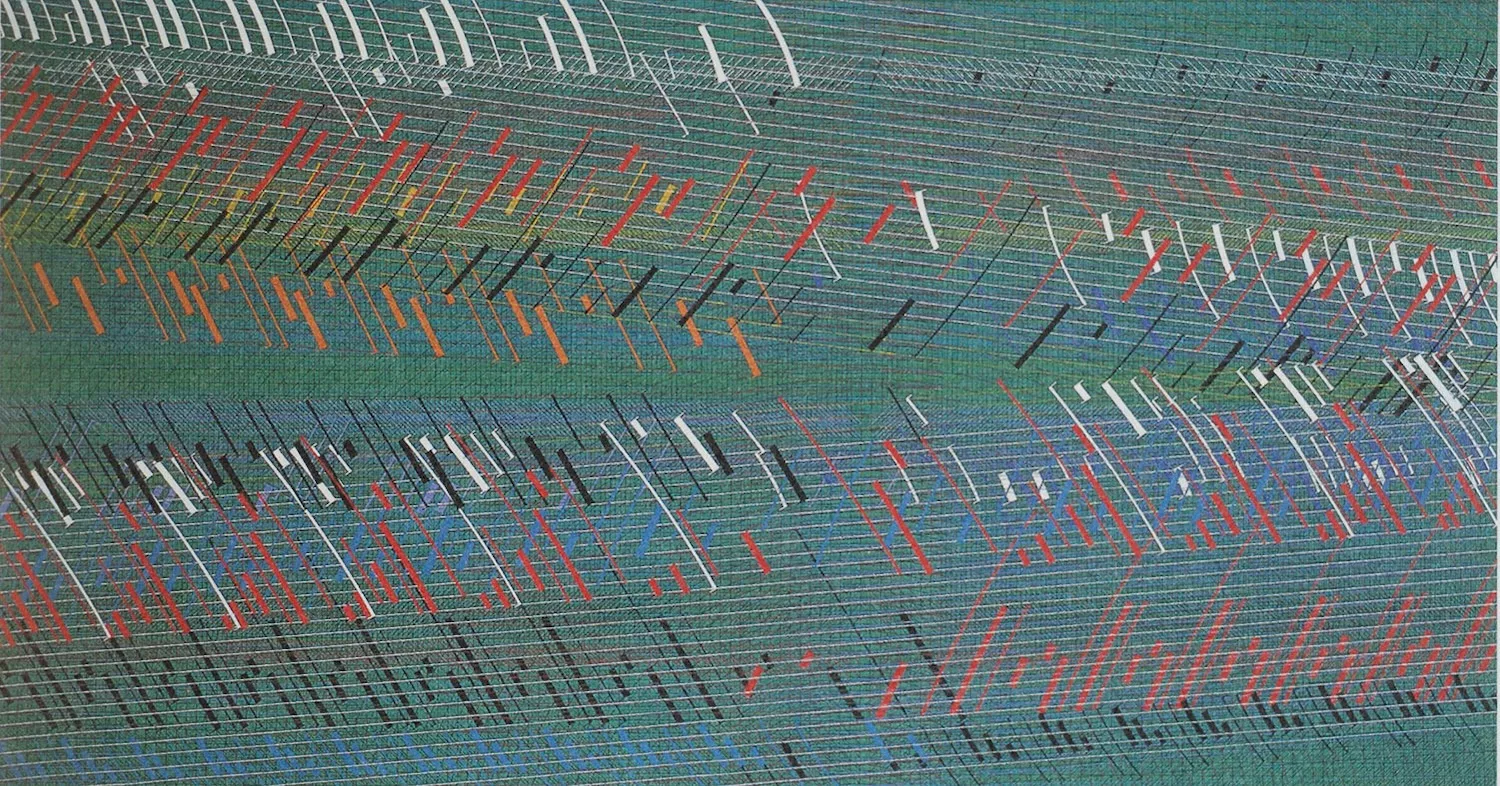

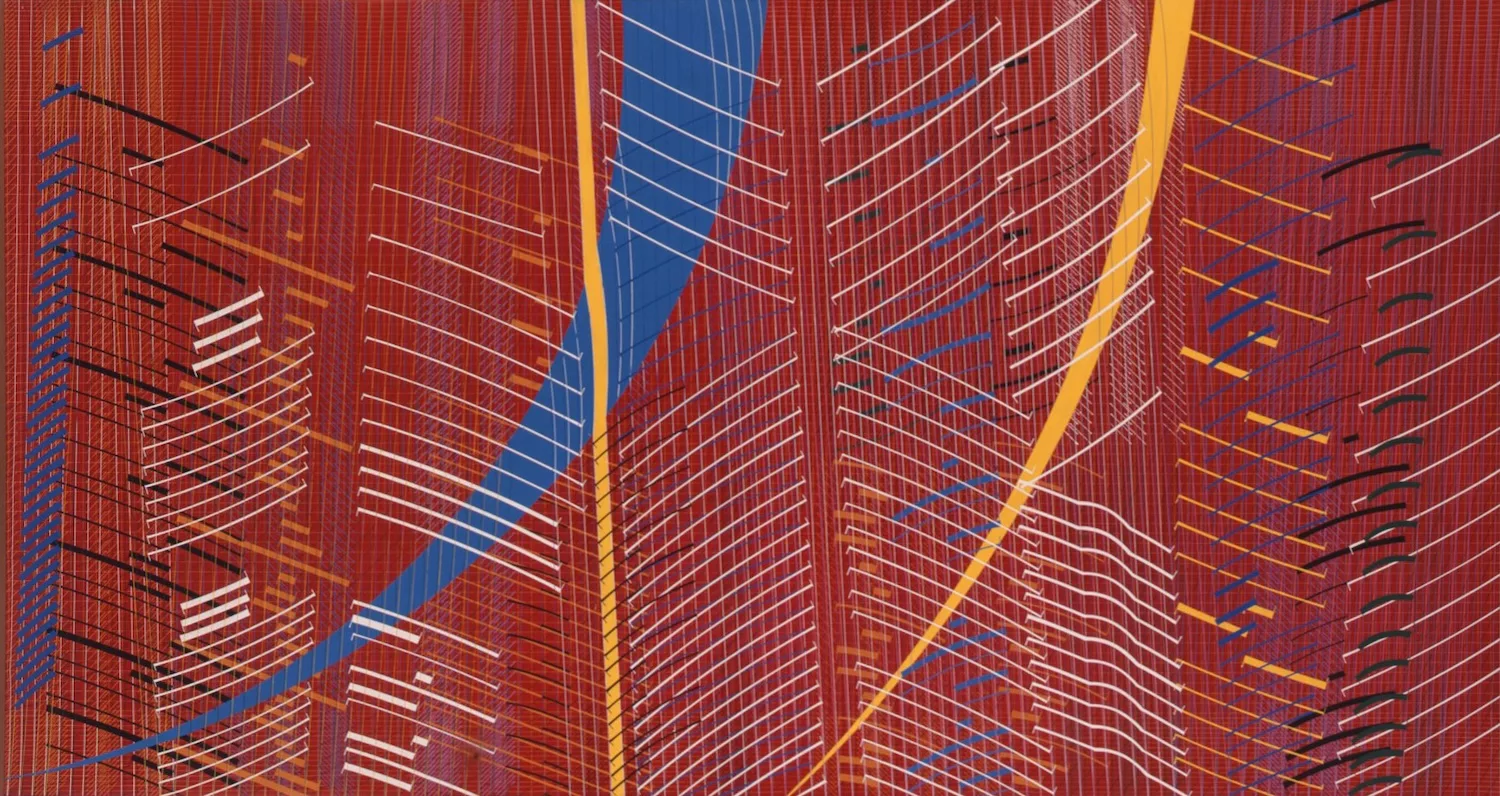

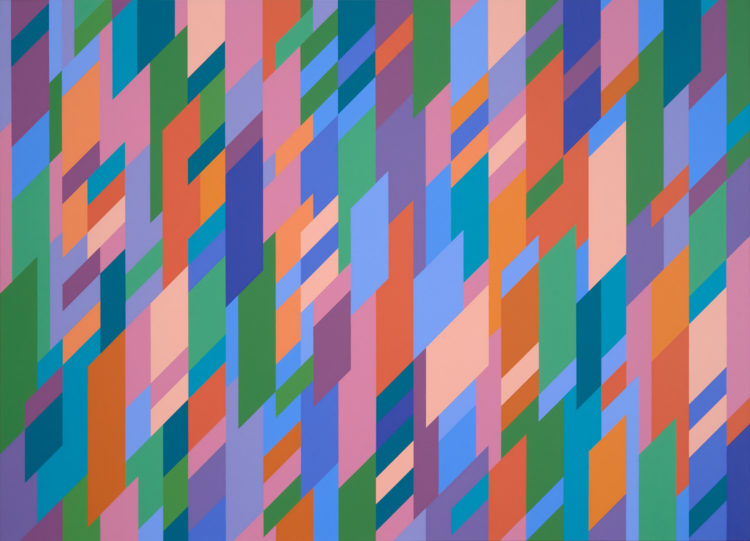

The composition of such novel poetry was furthered when, in July 1965, S. Kanno had the opportunity to move house to Tokyo for her husband’s work and join the Association for the Study of Arts (ASA) under the chairmanship of avant-garde poet Seiichi Niikuni (1925–1977). The ASA was a group focused on the creation of so-called “concrete poetry”—a form that foregrounds visual and auditory characteristics—and the close investigation of “words” themselves, which are marked by the integration of three components: shape, sound, and significance. Beginning in October 1965, S. Kanno spent roughly a year attending ASA meetings and contributing to its journal in parallel with her Gutai activities. This experience brought about a major turning point in her painting, which at that time had been stymied by a sense of deadlock. During this period, she got the idea to create visual poetry from the concept of musical rest notation and applied that concept to painting, turning her hand to the creation of paintings that were just like visual poems. Eventually, she began constructing images of Go board patterns made up of combinations of plus and minus symbols. By 1967, she had perfected an intricate, fine-drawn style—making free use of the ruling pen, or karasuguchi (lit. “crow’s beak”)—in which a complex pattern of short lines overlaps on horizontal and vertical axes. In 1968, she became a formal member of the Gutai group; works created before the dissolution of Gutai in 1972 include the From Alpha to Omega series (Arufua kara omega made, 1970) and the World of Lévi-Strauss series (Rebui-Sutorōsu no sekai, 1971).

In these works, the image emerges through the use of line density—or, put another way, the positional relationship of lines—rather than via outright depiction, but S. Kanno had already internalized the intrinsic components of this process through her composition of the poetry. This is because visual poetry is founded upon a relationship between all of its elements, including the size and configuration of each symbol and its relationship to the surrounding, blank space. Thus, we might say that, in the realms of both poetry and painting, S. Kanno was concerned with the “relationships” that exist between multiple elements, the “structures” that connect and unify them into one, and the universal “laws” that are inherent to them. Indeed, this is also evident in her relying on a sensitivity to “sound,” something that occupied an essential place in her poetry and painting work from the early 1960s onward. Truth be told, music itself is a genre that has its roots in the relationships between symbols like musical notes—which are not tied to concrete images—and the patterns that weave them together.

After 1974, inspired by physics lectures that she attended at the Faculty of Science, S. Kanno continued with the energetic production of large-scale works on that theme. These include Doppler Effect (Doppurā kōka, 1975–76), Black-Body Radiation (Kokutai fukusha, 1975–76), Expanding Elementary Particles (Hirogari o motsu soryūshi, 1981), and Equation Which is Filled Everywhere with Non-Differentiable Functions (Itarutokoro bibun-fukanōna kansūzoku no mitasu hōteishiki, 1988). Not only did she study elementary physics at this time, but also highly abstract fields such as electrodynamics, quantum mechanics, and quantum mathematics, subjects that explore the laws undergirding the phenomena of the natural world—a topic in line with S. Kanno’s goals up to that point. The expression of such laws as numerical formulae likely resonated strongly with S. Kanno, who had always been more focused on the relationships between objects than she was on the individual objects themselves.

A biography produced as part of the “Women Artists in Japan: 19th – 21st century” programme

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025