Laila Muraywid

Cardinal, Philippe, Makram-Ebeid Hoda (ed.), Le Corps découvert, exh. cat., Institut du monde arabe, Paris (27 March–26 August 2012), Paris, Hazan, 2012

→Cotter Suzanne, Contemporary Art in the Middle East, London, Black Dog Publishing, 2009

→Mikdadi Nashashibi, Salwa, Forces of Change. Artists of the Arab World, exh. cat., The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. (7 February, 1993–15 May 1994), Lafayette/Washington, D.C, International Council for Women in the Arts et National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1994

Présences arabes. Art moderne et décolonisation. Paris 1908-1988, Musée d’Art moderne de Paris, Paris, 5 April–25 August, 2024

→Artists Making Books – Poetry to Politics, The British Museum, London, 27 November 2022–18 February, 2024

→In the Age of New Media, Atassi Foundation, Dubai, 6 November–17 December, 2018

Syrian multidisciplinary artist.

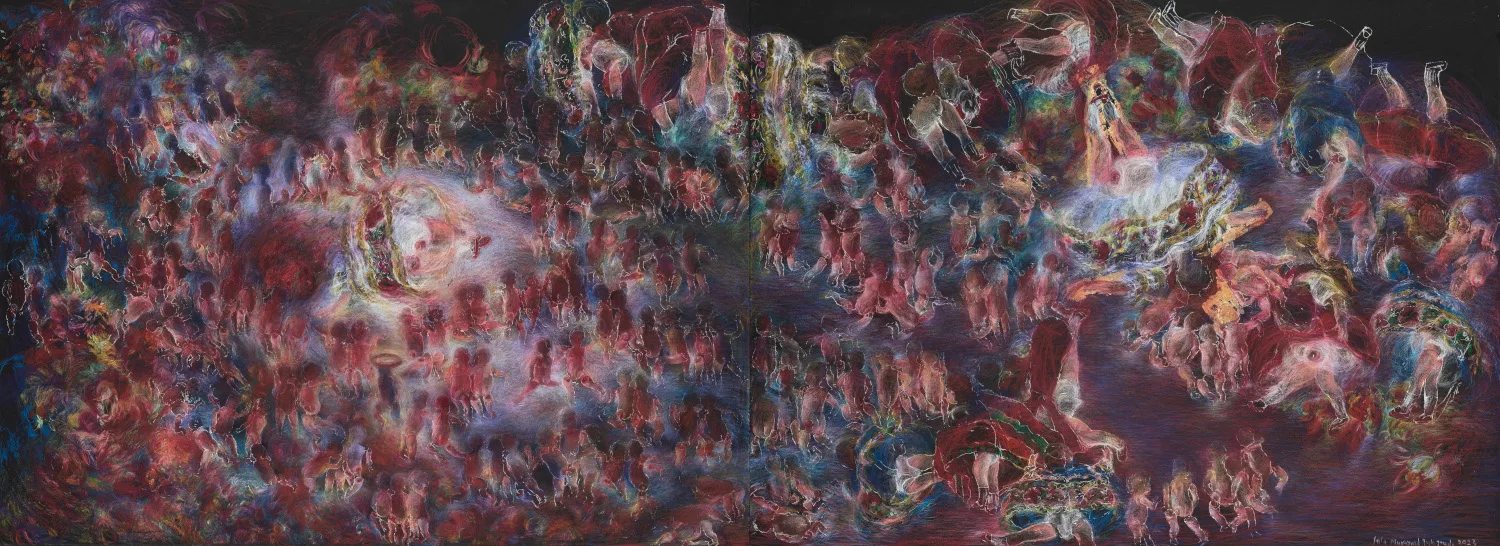

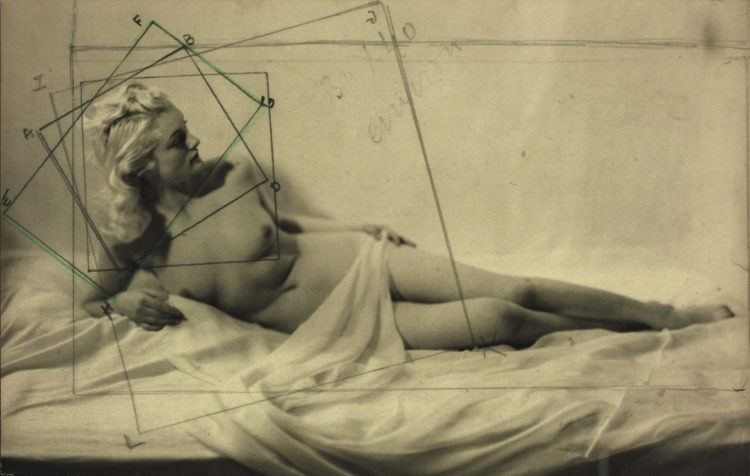

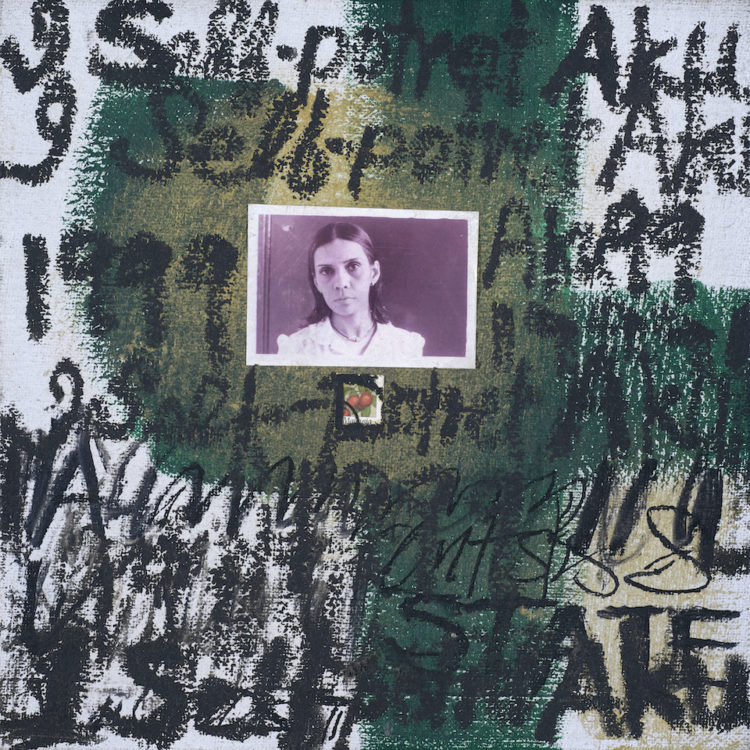

Over the course of her career, Laila Muraywid has developed a hybrid practice combining sculpture, photography, drawing and painting. At its heart, the female body is rendered with omnipresent, obsessive, violent and seductive techniques.

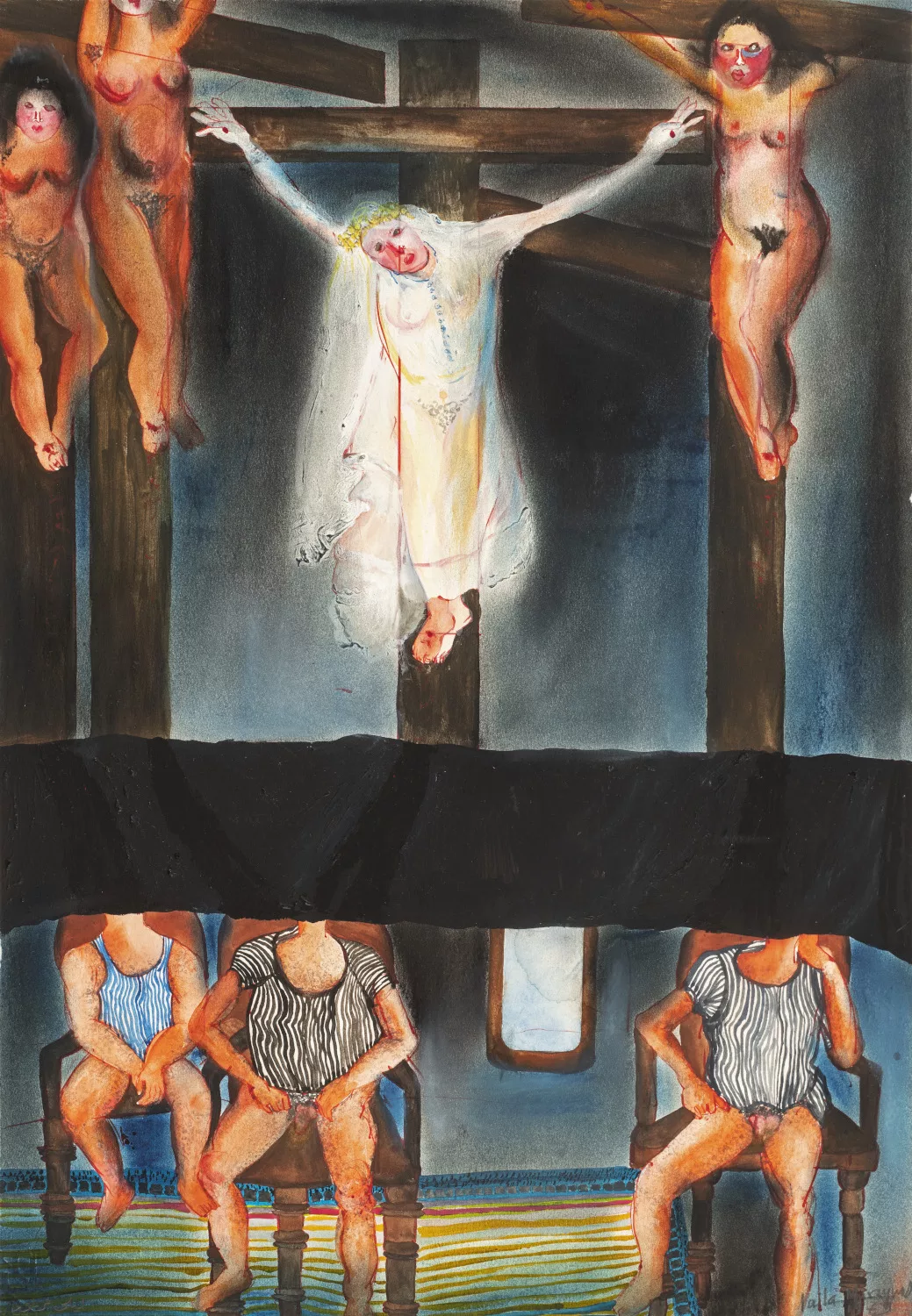

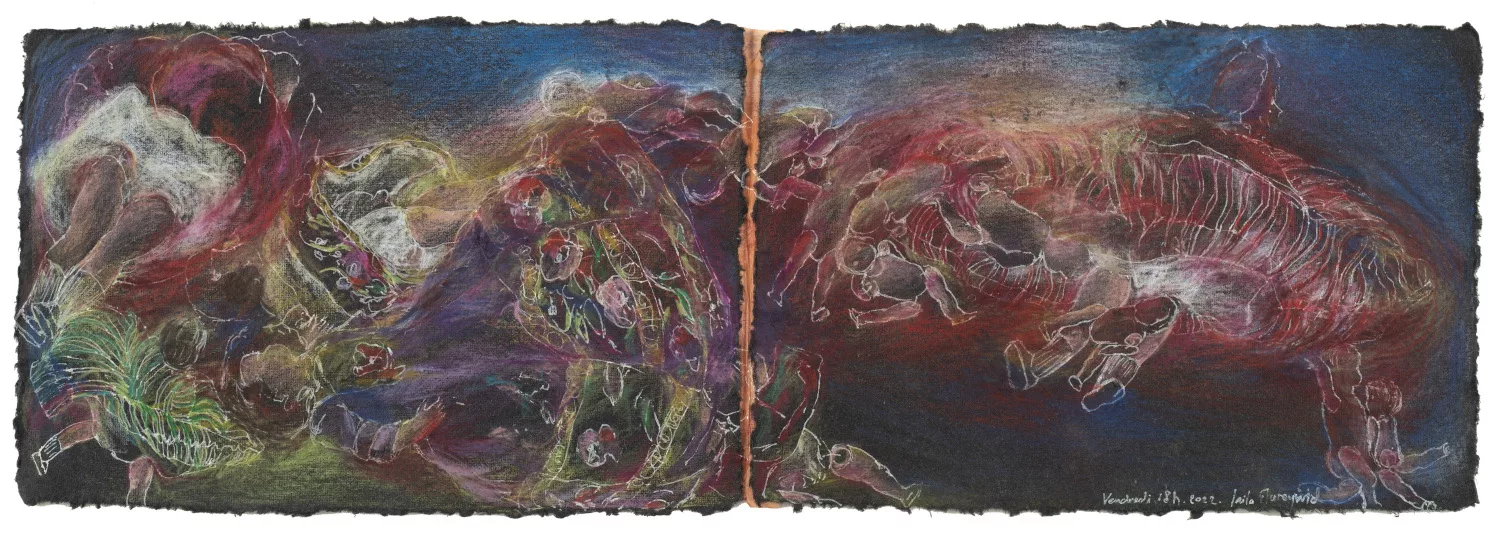

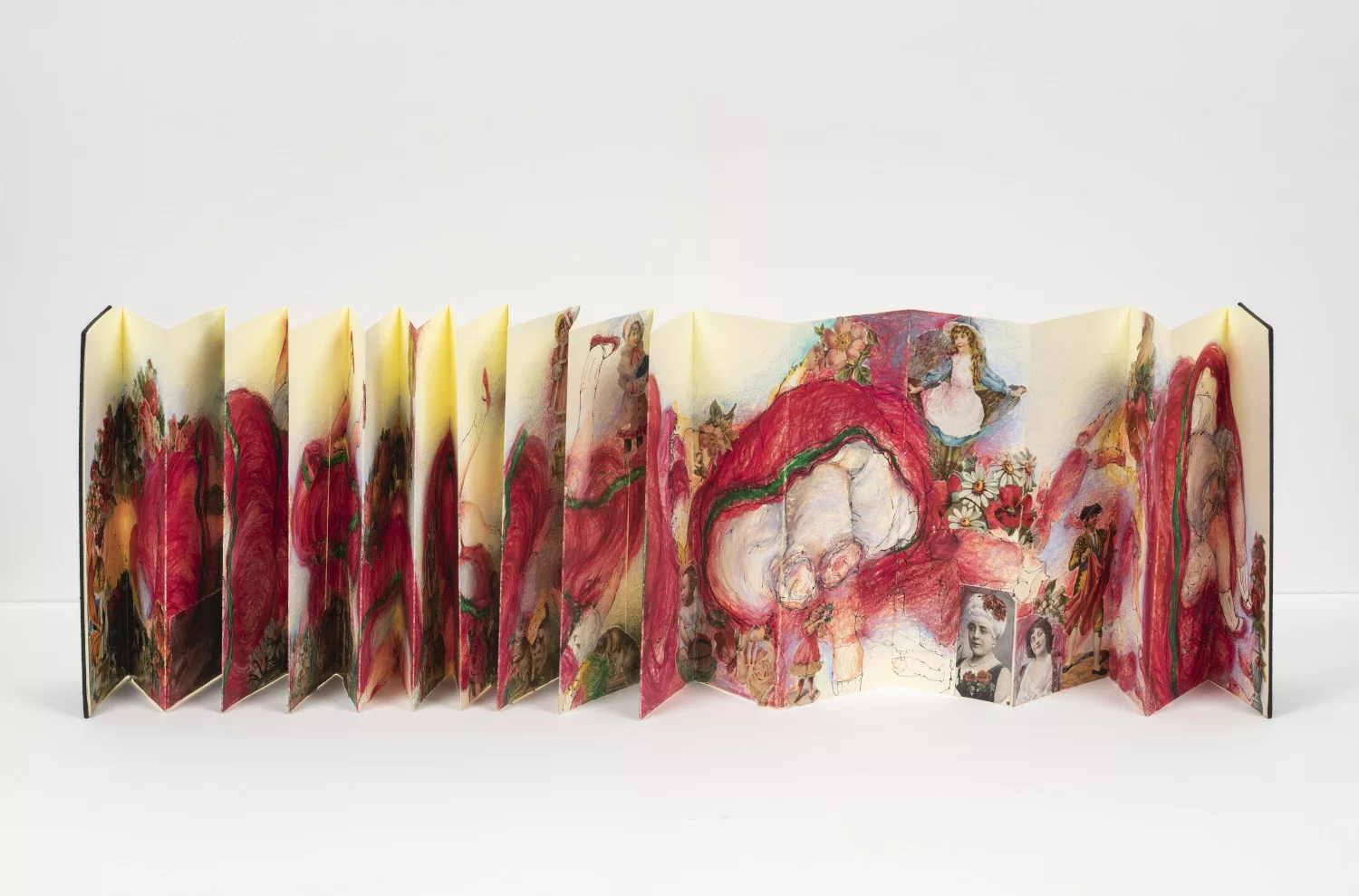

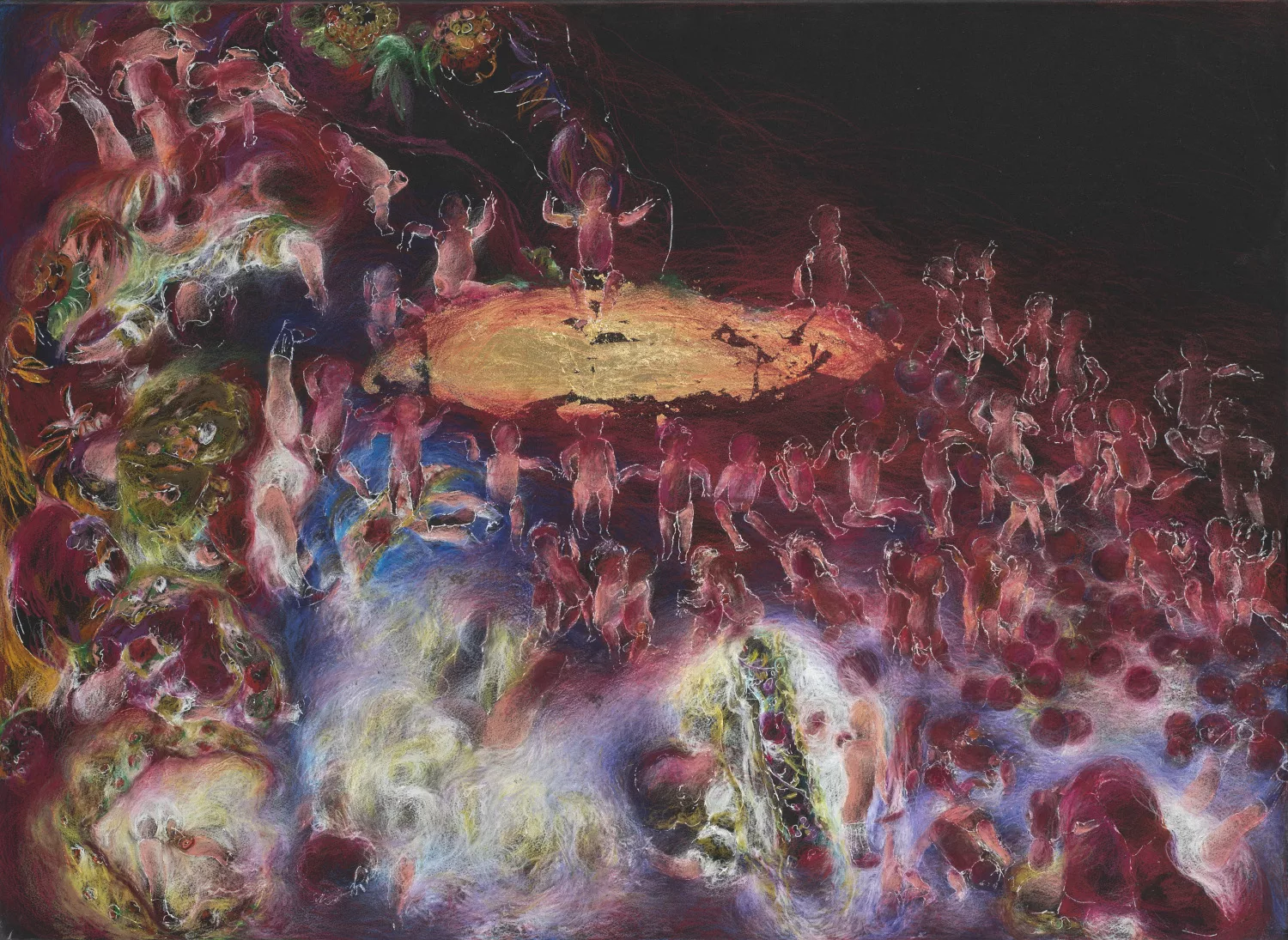

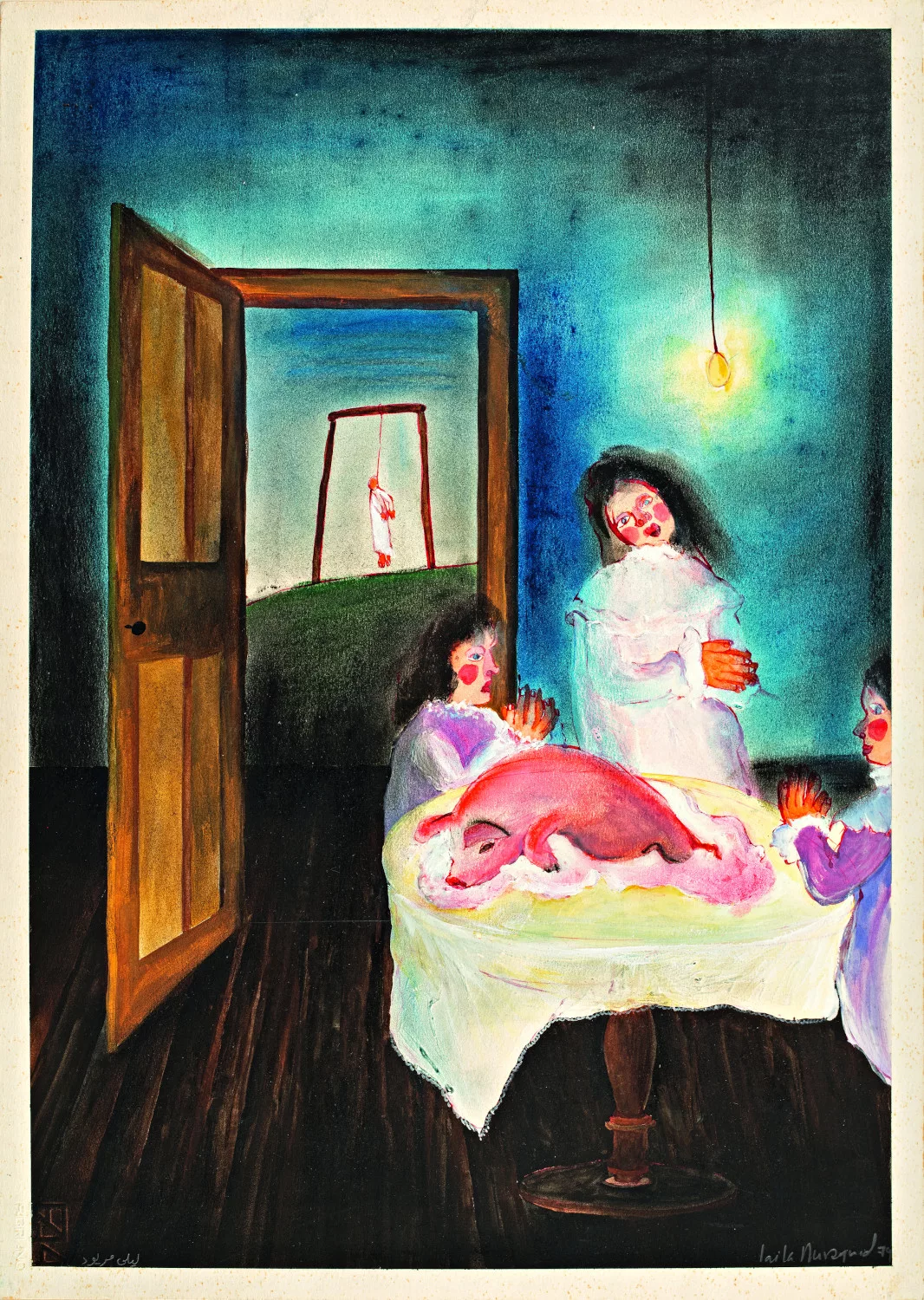

L. Muraywid gathered apples as a child in order to contemplate their decomposition, drawn to the tipping point at which goodness cedes to rot, beauty to horror. Throughout her oeuvre, the artist suspends in time this moment of passage from one threshold to another, resisting a dualist vision of the world. Horror exists in daily life just as beauty persists in tragedy. During a period spent in London in 1976, having relocated to escape the civil war in Lebanon, the country where she had lived until the age of eighteen, L. Muraywid visited museums and discovered their dearth of women artists. This merely reinforced her pursuit of her calling. In 1977 she returned to her native Syria, where she enrolled at the Damascus School of Fine Arts. Finding the teaching too academic for her taste, she began to look elsewhere for enlightenment, seeking out reality. In the butchers’ quarter in Damascus she sketched animal flesh, blood, viscera. In 1979 she held her first exhibition, at a cultural centre in Damascus, and presented a series of drawings of scenes of daily life such as meals alongside religious scenes of martyrs that, through the addition of one or more details, each veered into horror. A woman is crucified or hanged, the body relinquished to the public gaze and violated. The woman’s flesh is treated by men as a piece of meat. L. Muraywid thus reflects on the climate of terror in Syria from 1971, when dictator Hafez el-Assad seized power. What remains of civilisation during wartime, under totalitarianism? Terror does not confine itself to the public space – it invites itself into homes. The body, particularly the female body, is thus caught in a trap of religion, politics and intimate life. In 1981 the artist received a scholarship to pursue her studies in Paris. Not speaking a word of French, she developed her own language, a corporeal language. She took a place at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, where she discovered photography, while continuing with her engraving and drawing practices, working on paper she fabricated herself. In 1987, her first solo exhibition, entitled Icônes contemporaines [Contemporary icons], took place at the Espace Al Mutanabbi (Mission de la Ligue arabe – UNESCO). The preface to the exhibition was written by the poet Adonis.

Between 1996 and 2016, L. Muraywid created jewellery-sculptures, which were displayed in 2004 at the Musée Galliera. Enveloping and extending the body, these works in resin, stone and metal are also, for the artist, theatres of life, animated by light. The pieces constitute a departure point for a body of work that has been expressed through performance (from 1996) and photography, in which the body is simultaneously staged, exhibited and escaping. All Masks Have Faces was one of the first works to take this form. In 2011, L. Muraywid began work on a new sculptural project composed of fragments of casts of bodies, assembled using a resin conglomerate containing stones, jewels and chains. The Wedding is one piece from this series: the sculpture, its arms torn apart to reveal a magma of precious stones and repulsive viscera at its centre, calls into question the experience of the threshold between beauty and violence. When asked if she is a feminist, L. Muraywid replies, “Why should I be? It’s men who should be”.

A biography produced in partnership with the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris and Zamân Books & Curating within the scope of the programme Role Models

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025