Research

Kara Walker, The moral arc of history ideally bends towards justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestrained chaos, 2010, graphite and pastel on paper, 182.9 x 289.6 cm, Courtesy of Sikkema, Jenkins & Co., New York, © Kara Walker

Magic lanterns? Scenes of horror and guilty pleasures, more terrifying than the cruellest fairy tales. Thousands of little drawings halfway between surrealism and newspaper satire. A prestigious prize. Controversy. Bad puns. Books. Films. A retrospective. Enormous chaotic drawings with a touch of expressionism about them. Still more very bad puns. New scandals. A Sphinx made of sugar. Hundreds of interviews and exhibitions.

Kara Walker, The Moral arc of history ideally bends towards justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestrained chaos, 2010, graphite et pastel sur papier, 182,9 x 289,6 cm, Courtesy of Sikkema, Jenkins & Co., New York, © Kara Walker

All in the span of twenty years: from her exhibition at the New York Drawing Center in 1994 to her last two shows at the Victoria Miro Gallery in 2015, the work of Kara Walker has spanned a number of mediums, while remaining consistently faithful to a program defined by anti-racism and anti-sexism. Her work presents an endless variation on the relationship between violence and representation.

Reactivation of a minor genre for political ends: the silhouette

By now, Walker is famous for installations such as Gone, A History of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994), a parody of the famous Gone With the Wind. The feeling of déjà-vu experienced by the viewer when observing what appear to be shadow puppets disappears when, upon closer inspection, they realize that they are looking at shapes cut out of black paper; once wax-glued to the wall, they become so flat they seem to “vanish” into it1. The grotesque appearance of the characters and their actions, together with the act of cutting the figures out of their black background, is an attack on the idea of historical representation itself and on how slavery is remembered. The artist mentions history painting2 among the many eclectic sources that inspired the silhouette installations: thus, we are dealing with no less than the actual removal of figures from their background through the violent act of cutting.

The installations subvert the initial function of the silhouette, which were used in lieu of portraits towards the end of the 18th century and during the romantic era. Walker’s silhouettes “aim to suggest they capture the outlines of flesh and blood models3,” but they really are simulacra, imitations of portraits that have no models. Instead of models, Walker uses stereotypes. They quickly establish a link between the distortion of the history of slavery and symbolic violence. The characters that we will read as “slaves” (therefore black) are borrowed from racist caricatures (in the form of images or tchochkes) that flooded visual culture in America following the Civil War, a time when the myth of the refinement of the Old South, where masters and slaves lived together in peace and harmony, was taking root in American culture4 .

Kara Walker, Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart, 1994, Cut paper on wall. Installation dimensions variable; approx. 156 x 600 inches (396.2 x 1524 cm) Installation view: Selections 1994. The Drawing Center, New York, 1994 Photo: Orcutt Photo © Kara Walker, image courtesy of Sikkema, Jenkins & Co., New York

At the end of the 18th century, the carving out of profiles – the silhouette – had been appropriated by the practice of physiognomy, a pseudoscience that applied them to develop theories on so-called racial inequalities5. But also, and perhaps most importantly, due to their resembling shadows, Walker’s silhouettes present the shadow as the subject’s evil twin. And according to philosopher Lewis Gordon, the negative figure that opposed the idea of modernity that took shape during the Enlightenment was precisely the figure of the Black person, which historian Cedric Robinson notes is a purely Western fabrication6.

For Walker, both immersed in Adrian Piper’s conceptual art and passionate about oil painting, the silhouette was a deliberately adopted position. The early 1990s were marked by the rejection of painting. The prosperous part of the 1980s were characterised in the United States by a reactionary socio-political and aesthetic context, exemplified by the resurgence of somewhat chauvinistic neo-romantic positions focused on figurative painting, with increased speculation in the art world. When the financial crisis hit and investors withdrew from the art market, this was suddenly replaced by practices centred around cheap materials and casually-produced forms, resulting from a strong interest in identity politics, at a time when the art scene was expanding to include minorities7. In this context, oil painting was considered as a vehicle that spoke to, and for, a conservative social order8. The artist herself associated this medium with a patriarchal logic that would have placed her “at its margins somehow9.” Yet, the silhouettes also borrow their immersive spatial arrangement from the cyclorama – circular panoramic paintings rendered obsolete by cinema, aiming to allow spectators to experience a historical event in a fully immersive manner10. Walker identifies this type of grandiloquent oversized painting and silhouettes as minor art forms11. Their fusion enabled her to criticize a dominant form using marginal mediums.

Kara Walker, That Thing, 2005, pencil on paper 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm) © Kara Walker. Images courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Using anachronistic strategies to raise questions about the present

Anachronism is the structuring principle behind Walker’s silhouettes, who created them from the fictitious point of view of a black woman who would have lived “150 or 200 years ago,” who would not have had anything more than limited access to forms of artistic expression12. The medium thus highlights the implicit limitations confining the artistic practice of black women during the 1990s. The titles of the artworks, which often refer to the artist as the “Negress,” stress her ironic position, exaggerating the stereotypical expectations thrust upon minority artists. Moreover, from the very beginning the artist had associated the silhouettes with blackface13 : the silhouettes made all models black, which Walker ascribes to the latent and ambiguous desire to “become black” in Western culture, but which also relates to the visual artist’s strategy for positioning herself in a scene where the white majority would expect her to examine her “blackness.” Her humorously sensationalistic titles put forward the “artificiality14,” or performative aspect of this stance15.

Walker’s art is therefore not concerned with the past or with slavery16. Unlike Fred Wilson in Mining the Museum (1993)17, it is not a question of working as a historian or coming to terms with a traumatic past. According to art historian Darby English, the installations give the illusion of being “images of slavery”; what is at stake is shattering the possibility of representation itself, by suggesting that the memory of slavery has been buried and irrevocably transformed by its representations18.

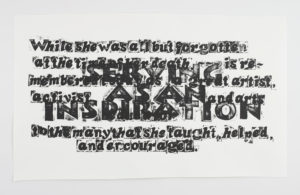

Kara Walker, Nina Simone, 2010, unique ink transfer on paper 59.5 x 72.25 inches (151.1 x 183.5 cm) © Kara Walker. Images courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Kara Walker, Augusta Savage, 2010, unique ink transfer on paper 43.625 x 72.25 inches (110.8 x 183.5 cm) © Kara Walker. Images courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Deadly representations

The silhouettes address both the symbolic violence of the representations of slavery and their effects on contemporary consciousness, namely the real impact of the images and representations. They reflect the back-and-forth motion between mental constructs and concrete, visual representations that infect daily life19. They illustrate this phenomenon by only revealing the “identity” of the characters if we accept to identify their racial profile20 (pointed nose = “white,” thick-lipped = “black”), that is, to recognize that we know how to read signs related to the reduction of individuals into caricatures. In that way, the silhouettes are deeply conceptual since they must be activated, not only through the act of perception, but also through the personal history and social position of the observer21.

Given the semantic and historical richness of the installations, we can see that it can be difficult to avoid boiling down Walker’s work to those installations alone. Yet the majority of Walker’s creations examine the crushing weight of representations. Thus, starting in 2007, the visual artist introduced a series called Search for Ideas supporting the Black Man as a Work of Modern Art – Contemporary Painting. A death without end: an appreciation of the Creative Spirit of Lynch Mobs, including fifty-two texts written in sumi ink on paper arranged in the form of a minimalist grid22, exclamations and interior monologues using ultra-violent (often vulgar) language and descriptions of actions (rape, circumcision, murder, torture, expropriation). Walker had created this series as a response to images of tortured Iraqi prisoners detained in Abu Ghraib that had surfaced on the Internet two years before. Confronted with these omnipresent images, Walker preferred to use text instead: a metaphorical black body referring back to the violence perpetrated against the racialised enemy (and in American English, one of the racial slurs used to designate Arabs is “sand nigger”) – Black here constituting the universal Other, as defined by Western racist terms.

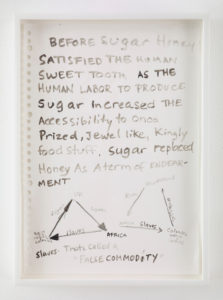

Kara Walker, From: Sugar Makes This World, 2013-14, ink, watercolor and graphite on paper. One form a set of 19, 11.75 x 8.25 inches (29.8 x 21 cm) © Kara Walker. Images courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

To put the Kara Walker controversy to rest

To consider Walker’s work as a criticism of representation and of the violence at stake in representation also allows us to understand the controversy that has marked her career to the point of being mentioned in nearly every interpretation of her work23 . In 1997, a letter-writing campaign was initiated by artist Betye Saar to prohibit the exhibition of Walker’s work; it was later supported by artist Howardena Pindell24 . Walker was accused of perpetuating the negative representation of African-Americans and to sully the memory of slaves in an opportunistic or oblivious manner. Clearly, the exceptional character of Walker’s artistic rise to fame in the 1990s, in a similar fashion as Jean-Michel Basquiat, implicitly betrayed the narrow-mindedness of the art establishment with respect to artists with minority backgrounds25. The issue of representation became socio-political, showing that for any artist coming from a social minority, there exists a requirement for a total representation of the group with which he/she is identified. And the controversy revealed what historian Hal Foster described in “The Artist as Ethnographer ?” as the relegation of the responsibility of political commentary to artists from marginal backgrounds (social or geopolitical)26.

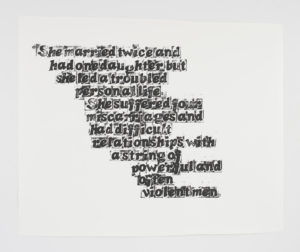

Walker’s position as a black woman, a very specific minority, probably had a certain influence in this instance27.The proliferation of explicitly sexual images in her work is perhaps one of the reasons why “the controversy” was so overly heated – the issue of the representation of the sexuality of black women being further complicated by the concealing of their sexual exploitation, combined with the development of their fictitious excessive sexuality28. Art historian Lisa Gail Collins reminds us that black female nudity was problematic in art for a very long time: in general absent from the canon29, and if represented, it came back to perpetuating the hypersexualized image of black women that had been used as an excuse to legitimize systematic rape under slavery – and colonialism30. In this context, the re-defining of black femininity (socially acceptable, and thus bourgeois and heterosexual) by African-American women largely implied the denial of the body31. According to critic Hilton Als, we had to wait for the photograph of Michelle Obama at the inauguration of the 44th President of the United States (2008) to put an official iconographic end to the “mortification” of the black female body32. Yet Walker’s creations feature many images of black women concerned with the pursuit of pleasure. While the body of the artist is never present, not even as self-portraits, we can nonetheless assume that it was the representation of sexuality by a black woman that caused such an uproar. All the more so given that the represented sexuality was often contradictory, perverse – as seen in That Thing (2006). However, the use of sexuality in Walker fulfils a largely allegorical function: in this drawing, made in obvious bad taste, the activities the feminine figure engages in primarily refer to the masturbatory element involved in ruminating about the past and about history.

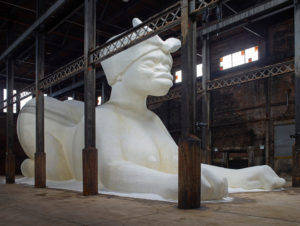

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, 2014, polystyrene foam, sugar Approximately 426 x 312 x 906 inches (1,082 x 792.5 x 2,301.2 cm) A project of Creative Time Domino Sugar Refinery, Brooklyn, NY, May 10 – July 6, 2014 Photo: Jason Wyche © Kara Walker. Image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Kara Walker, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, 2014, polystyrene foam, sugar Approximately 426 x 312 x 906 inches (1,082 x 792.5 x 2,301.2 cm) A project of Creative Time Domino Sugar Refinery, Brooklyn, NY, May 10 – July 6, 2014 Photo: Jason Wyche © Kara Walker. Image courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Towards an Afro-Feminist rewriting of world history

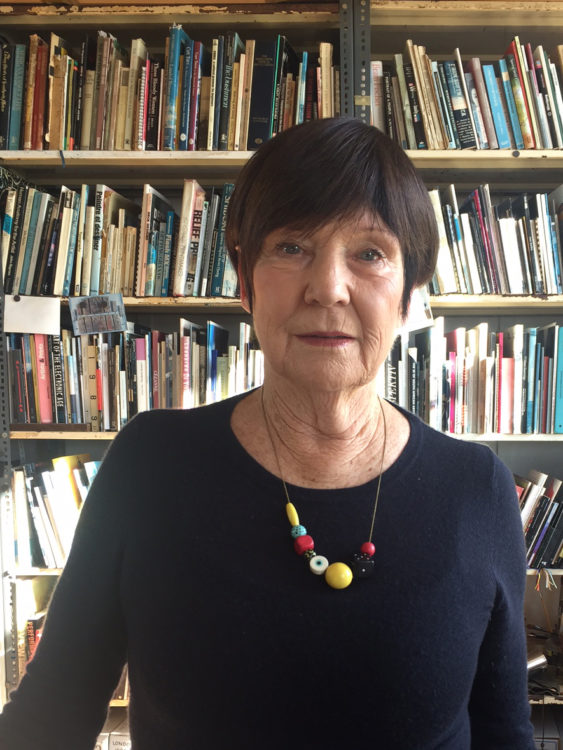

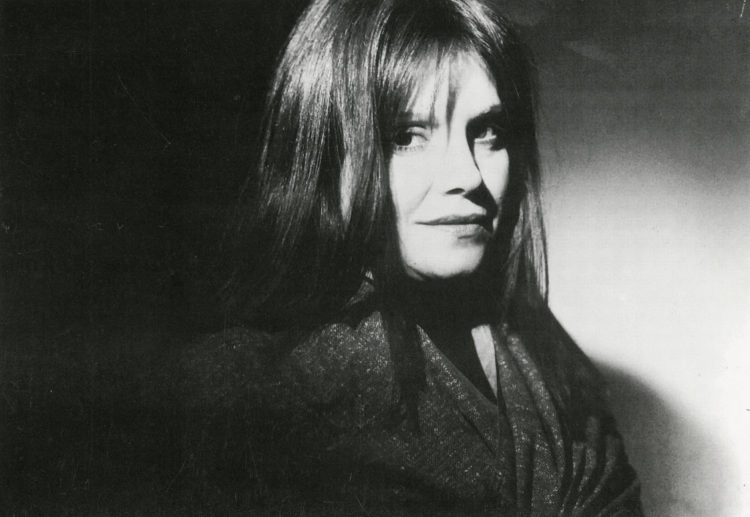

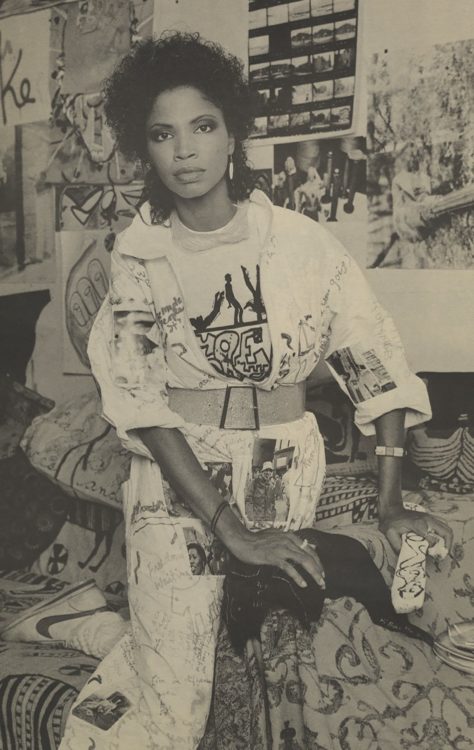

Walker’s art must therefore be considered in afro-feminist terms. Her series of monotype textual prints (2010), excerpts from various Internet sources (namely Wikipedia), touches on the issue of so-called representative women: figures with whom a famous black artist like Walker is supposed to identify33. Only one visual artist is included in this pantheon, sculptor Augusta Savage (1892–1962), alongside Billie Holiday and Nina Simone. The selection of historical rather than contemporary figures does not suggest the return of the past inside the present, since the Wikipedia entries are recent, but calls attention to the miserabilism and voyeurism at play in the historiography of these artists and is a reminder of the current weight of race and gender in how art is received.

To this is added Walker’s examination of a history – and present – subjected to globalization. This element of the work became more prevalent during the 2000s and 2010s, as demonstrated by her interest in themes that were less and less specifically American. The temporary exhibition at the Domino Sugar Factory (commissioned by Creative Time), A Subtlety or The Marvelous Sugar Baby34 (2014) consisted of a monumental Sphinx covered with a white sugar solution, which looked like a stereotypical black nanny, flanked by caramel figures that were slightly smaller than the average adult spectator. Based on research into the history of sugar cane culture, the highly odorous and physically volatile installation condemned the systematic erasure of black slaves from the written history of Western modernity: no slaves, no sugar money for Western powers ; no colonial profits, no Revolution – whether American or French35. And the fact that she chose to depict a black woman showing her behind reminds us that it is on the double exploitation of black women (in terms of labour and sex) that empires were built. At the same time, the choice of stereotype and the scandalous position use humour as an instrument to create distance from the burden of trauma – a constant in Walker’s work.

Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma at Teatro La Fenice, Venice Italy. A special project of the 56th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia. May 20 – June 6, 2015 Director, Art Director, Costume Designer: Kara Walker Associate Director: Ann-Christin Rommen Photo: Lucie Jansch © Kara Walker. Images courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

That Walker has chosen, upon an invitation from curator Okwui Enwezor to participate in the 56th Venice Biennale, to relocate Vincenzo Bellini’s opera in colonial sub-Saharan Africa, fits into this vision of globalized history. The play by French romantic playwright Alexandre Soumet, that inspired Felice Romani’s libretto, drew from a mythical Gallic past to invent glorious roots for French nationalism, while Romani used the same to mirror the building of Italian nationalism. Yet, these nationalisms with legendary sources were used to support the European colonialist impulse at the end of the 19th century. To make Norma a colonized African thus resonates particularly well with the ideological foundations of the opera. Hence, Norma confirms one of the many strengths in Walker’s work: her ability to freely manipulate established representations and the myths which collective identity rests on.

Vanina Géré is a former ENS-Lyon student, Global Visiting Scholar at NYU, and graduate of Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris 3 University (2012). Her doctoral thesis examined the work of American visual artist Kara Walker (Chancellerie des Universités de Paris Prize 2013). A specialist in American contemporary art, Géré teaches art history at the École Supérieure d’Art et de Design in Nancy; she is an active art critic and translator of writings on Art.

Walker, “Kara Walker talks with her father, Larry Walker, for Bomb’s Oral History Project,” BOMB Magazine, May 8, 2014, [online], http://bombmagazine.org/article/1000130/kara-walker-larry-walker, last consulted on 11/01/2016, 14/45.

2

Walker, quoted in Lawrence Rinder, “An Interview with Kara Walker,” in Kara Walker: No Mere Words, from the exhibition programme notes, April 3 – May 15, 1999, Oakland: California College of Arts and Crafts and the Capp Street Project, 1999, p. 46-47.

3

Anne Wagner, “Kara Walker: The Black-White Revelation” in Ian Berry et al., Kara Walker: Narratives of a Negress. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003, p. 95.

4

On the coincidence between the period following slavery and the surge of racist caricatures, see Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in Thelma Golden, Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994, p. 14. As a big collector of images and Americana, Walker often mentions the place racist caricatures have in her work. The most significant example is the visual essay that accompanies the travelling retrospective catalogue.

5

Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, Seeing the Unspeakable: The Art of Kara Walker. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004, p. 20.

6

Lewis R. Gordon, Bad Faith and Antiblack Racism. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 1995; Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000, First Ed. 1983.

7

In the United States, this expansion had found institutional recognition via two major exhibitions: the Decade Show in 1990 (New Museum, Studio Museum in Harlem and Museo del Barrio) and the Whitney Museum of American Art Biennale in 1993.

8

Norman Bryson, “Maudit: John Currin and Morphology,” in Kara Vander Weg, John Currin. New York: Rizzoli Books, 2003, p. 20.

9

“I felt like painting was bound up with an idea of patriarchy that did not necessarily have me in its best interests as a viewer, appreciator, colleague… I didn’t feel like I was a peer to the kind of painting that I actually enjoyed and admired… How was my understanding of painting at odds with where painting would place me? Painting would place me at its margins somehow.” (Walker, “Kara Walker Talks with her father, Artist Larry Walker”, p. 13/45.)

10

Walker’s primary reference is the cyclorama depicting the battle of Atlanta, the city where Walker spent her teenage years and completed the first part of her art studies, and to which she paid anti-homage, with her exhibition in London’s Victoria Miro Gallery, Go to Hell or Atlanta, Whichever comes first (Nov. 1 – Dec. 7, 2015).

11

Walker, quoted in Rinder.

12

Walker, quoted by Mattea Harvey, “Kara Walker by Mattea Harvey,” (BOMB Magazine, Summer 2007, n°100, p. 74-82). Paper cut-outs cannot fail to recall the American feminine craft of patchwork. In some of her collage work, Walker incorporates de idea of collusion between the proto-abstraction of patchwork and the modernity of art based in large part on the cultural appropriation of vernacular forms: Procession for the Negro Folk (hero); Authenticating the Artifact (2007).

13

A practice that gained popularity in the United States and the United Kingdom around 1820, consisting in white actors applying coal to darken their face in order to perform caricatures of black slaves and people of African descent (legitimizing their subjugation and poor treatment by representing them as subhuman creatures, impervious to pain), blackfaceappeared countless times on the silver screen (see D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a nation, 1916) then on television, by white and black actors, and became widespread throughout all Western cultural forms. Blackface shows up from time to time in contemporary art, whether to raise questions about symbolic systems through performance as in Bruce Nauman (Art Make-Up, 1967); as a blatantly racist metaphor in Donald Newman (Nigger Drawings, 1979); in an explicitly ironic and critical manner as in Xaviera Simmons (One Day and Back Then, 2007); or even as a form of benevolent racism (negrophilia) and cultural appropriation in order to move beyond history and politics as in Lili-Reynaud Dewar (I am Intact and I don’t Care, 2013). To further investigate blackface, see Spike Lee’s film Bamboozled (2000); Lott, Eric, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, Oxford University Press, 1993; Rogin, Michael, Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot, Berkeley: University of California Press,1998; W.J.T. Lhamon, Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop.Harvard University Press, 2000. (I’d like to thank Peggy Pierrot for pointing out this last publication.)

14

In a drawing from her series on negative and positive stereotypes, Do You Like Creme in Your Coffee and Chocolate in Your Milk? (1997), Walker writes: “I knew that the only way to gain an audience was to cloak my work in the guise of BLACKNESS I would have to make work that was so directly racial that no one could HELP but notice. And/But at the same time I was questioning the artificiality (genuineness) of this attitude (stance)…”

15

Take for example one of the longer titles from Walker’s first entirely circular installation, vaguely inspired by Eastman Johnson’s painting Negro Life at the South (1859): “Slavery! Slavery! Presenting a GRAND and LIFELIKE Panoramic Journey into Picturesque Southern Slavery or “Life at ‘Ol’ Virginny’s Hole’ (sketches from Plantation Life)” See the Peculiar Institution as never before ! All cut from black paper by the able hand of Kara Elizabeth Walker, an Emancipated Negress and Leader in her Cause).”

16

See Darby English, “This Is Not About the Past: Silhouettes in the Work of Kara Walker,” in Ian Berry et al., Narratives of a Negress, p. 140-167.

17

It was a temporary display featuring the Maryland Historical Society’s museum’s collections, created by Wilson following a research residency conducted on these same collections. The exhibition (1992-3) turned out to be a milestone considering the daring and relevance it exhibited by connecting art and decorative art objects and artefacts related to slavery. Mining the Museum sparked a long string of artists invitations, where they were asked to mount exhibitions based on museum collections. See Huey Copeland, “Fred Wilson and the Rhetoric of Redress,” in Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear: Art, Slavery, and The Site of Blacknes in Multicultural America, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2013, p. 25-64.

18

Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007, 89, 94, 82.

19

In this way, Walker’s work also tackles fiction, those little stories we tell ourselves to justify wrongdoings, as well as racist stereotypes, which are also entirely fictional. Police violence against Afro-Americans has received wide media coverage over the last five years. Rooted in these stereotypes, which had already begun feeding and legitimizing acts of permanent terror against Afro-Americans even before the Civil Rights Movement, this violence demonstrates how deeply these representations are rooted in American society.

20

In the sense of police profiling.

21

Philippe Vergne, curator of the retrospective, was the first to insist on the conceptual dimension of the silhouettes. However, taking the socio-racial position of the spectator into account in conceptual art points to the profound influence of Piper’s work on Walker. Vergne, “The Black Saint Is the Sinner Lady,” in Philippe Vergne, Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love. Exhibition Catalogue. Walker Art Center, Feb. 17 – May 13, 2007, Whitney Museum of American Art, Oct. 11 – Feb 3, 2008, UCLA Hammer Museum, Feb. 17 – May 11, 2008. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2006. See Walker, “Kara Walker Speaks with her father, artist Larry Walker,” p. 30/45).

22

Yasmil Raymond, Abstract Resistance. Exhibition Catalogue. Walker Art Center, Feb. 7 – Mar. 23, 2010. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, p. 21-22.

23

All things being equal, it would be like reading something about Warhol without his famous “I want to be a machine” being mentioned.

24

See also the anthology of writings on the controversy compiled by Pindell. Howardena Pindell et al. Kara Walker: Yes/Kara Walker: No/Kara Walker? New York: Midmarch Art Press, 2009. See Géré, cited thesis. It’s important to note that this kind of controversy is common in Afro-American art history – Ralph Ellison had caused a scandal with Invisible Man (1952), considered by certain members of the black American bourgeoisie as a “stab in the back.” (English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, p. 65.)

25

The parallel with Basquiat, while obvious, was nonetheless limited in scope. Other than Basquiat dying at a very young age, the difference between their two trajectories lies in the fact that Walkers was first noticed by cultural institutions rather than collectors, and that her work was supported by art historians from the very beginning, which was not the case with Basquiat. Moreover, arriving ten years later on the scene, Walker’s work benefitted from the critical contributions of an entire new generation of Afro-American curators and art historians who were sensitive to her postmodern approach, from Thelma Golden to Hamza Walker, etc.

26

Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer ?” in Hal Foster, The Return of the Real.Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1996, p. 171-204.

27

Here, we are clearly alluding to the specificity of the discrimination that black women can be subjected to, theorized under the term “intersectionality” by Afro-American legal expert Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989.

28

Sander L. Gilman, “Black Bodies, White Bodies: Towards an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and Literature,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 12, no1: “Race, Writing, and Difference,” Fall 1985, p. 204-242.

29

Female beauty and the notion of feminine itself, being white.

30

Lisa Gail-Collins, The Art of History: African American Women Artists Engage the Past, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 2002, p. 12-45.

31

Gail-Collins, op. cit., p. 53.

32

Hilton Als, “The Red Dress,” in Kara Walker: Norma, Exhibition Catalogue, Victoria Miro Mayfair, London, Nov. 13, 2015 – Jan. 16, 2016, London, Victoria Miro, 2015, p. 4-8.

33

Walker describes this series as an implicit examination of her own status as a famous artist. Josephine Baker is not included, probably because Walker had already run out of quotes from this figure by using them in a number of her pieces, the most notable being Endless Conundrum, An African Anonymous Adventuress (2001).

34

The full title is as follows: A Subtlety or The Marvelous Sugar Baby: An Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant.

35

For more about the scale of the enrichment of the French bourgeoisie as a result of colonizing what is now Haiti, as well as the long-term political impact it has had, as we well know, see the introduction to Black Jacobins, by CLR James (1938).

Vanina Géré, "Representation as Violence: The Art of Kara Walker." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/de-representation-violence-lart-de-kara-walker/. Accessed 31 August 2024