Michaelina Wautier

Michaelina Wautier, Self-portrait, c. 1650, oil on canvas, 120 × 102 cm, private collection

Gruber, Gerlinde, Katlijne Van der Stighelen, and Julien Domercq (eds.), Michaelina Wautier, exh. cat. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (September 30, 2025 – February 22, 2026); Royal Academy of Arts, London (March–June 2026), Veurne, Hannibal, 2025/26

→Martina Griesser, Gerlinde Gruber, Elke Oberthaler and Katlijne Van der Stighelen (eds), Workshop Practice: Supplement to Michaelina Wautier, Painter, KHM-Museumsverband, Vienna, 2025, DOI: 10.60477/mm49-mx04

→Christopher D. M. Atkins and Jeffrey Muller (eds), Michaelina Wautier and The Five Senses: Innovation in 17th-Century Flemish Painting, CNA Studies 1, Boston, 2022

→Van der Stighelen, Katlijne (ed.), Michaelina Wautier (1604–1689): Glorifying a Forgotten Talent, exh. cat. MAS, Antwerp (1 June–2 September), Antwerp, BAI, 2018

Michaelina Wautier: Painter, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, September 30, 2025 – February 22, 2026; Royal Academy of Arts, London, March–June 2026

→Michaelina Wautier (1604–1689): Glorifying a Forgotten Talent, MAS, Antwerp, June 1 –September 2, 2018

Southern-Netherlandish Painter.

Michaelina Wautier was active in mid-17th century Brussels and defied conventions by showing technical skill in all subjects from still-lifes and portraits to history paintings. Although little is known about her life–without records of her training or personal letters–she is now recognised as one of the Baroque period’s foremost artists. No baptismal record exists but official documents call her ‘Michelle’, suggesting she adopted the Latinised ‘Michaelina’ as an artist name. She was born in around 1614 to a family from Mons with no known painters before her and her brother, Charles Wautier (1609–1703). They had intellectual and noble connections, like the de Mérode family, which ensured her education. After her father’s death in 1617, her mother stayed financially stable and never remarried, living until 1638.

It is unclear if M. Wautier had already moved to Brussels by that date. It is likely that her older brother Pierre, a cavalry captain, had lived in Brussels since the 1630s, and M. Wautier had ties to Antwerp through her half-brother Albert, who lived there. Two of her 1652 dated panels are marked with ‘Antwerp hands’. She never married, and lived with her brother C. Wautier – himself also single and a painter – who is assumed to have taught her. In 1642 he rented a house in Brussels, possibly sharing a workshop with her. His guild membership came in 1651, after years of painting without one. He ‘trained abroad’ but where – possibly in Italy – remains unknown. M. Wautier’s only known drawing showing the Medici Ganymede (c. 1640–50) may hint at an Italian journey, but this is uncertain. She is the first known female artist in Northern Europe to draw ancient sculptures and reference antiquities in flower painting.

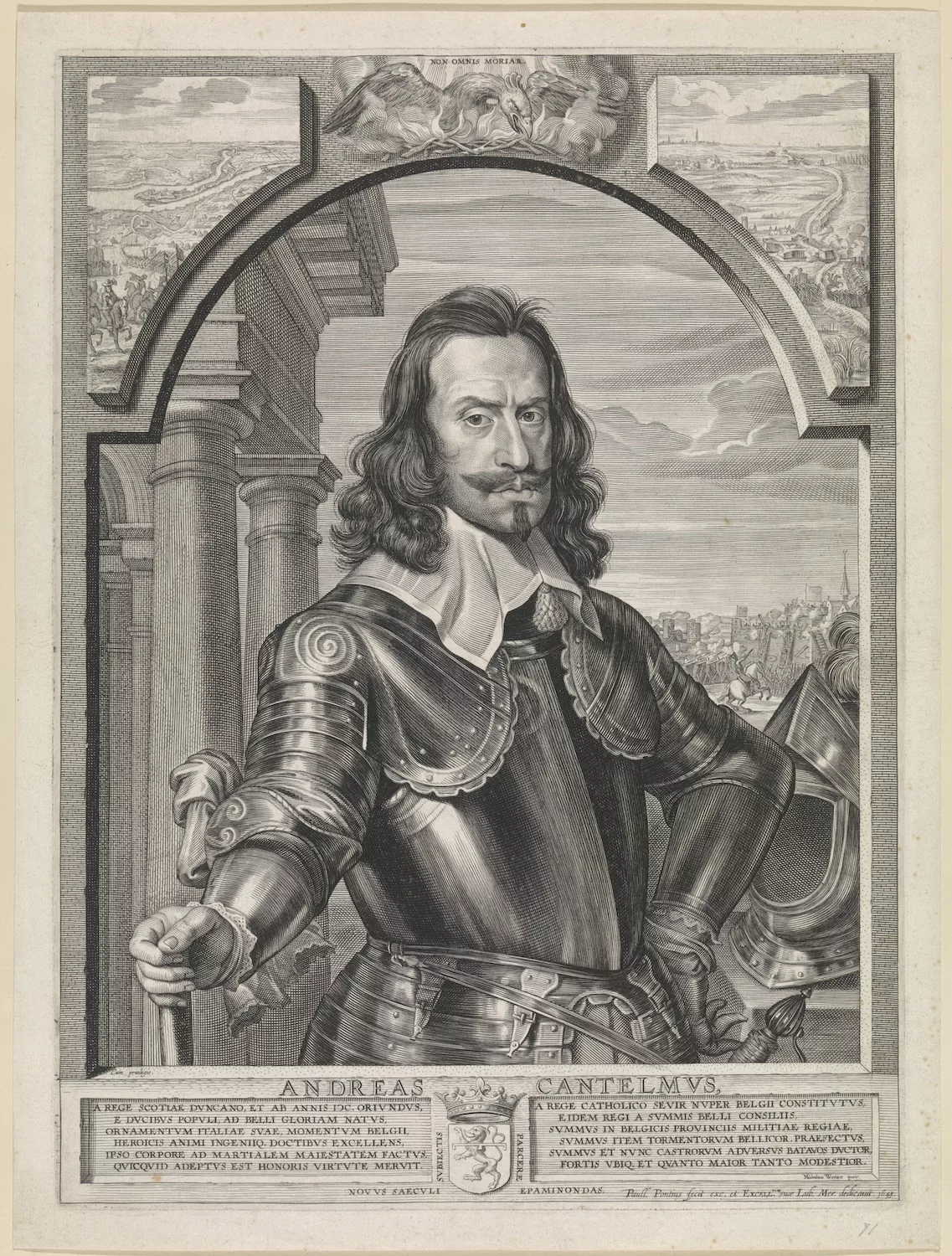

Her style is reminiscent of Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) and Caravaggesque painters such as Theodoor van Loon (1581–1649), but she used these influences in her own subtle way. Her earliest works are portraits of important Spanish officers, such as Andrea Cantelmo (1643). The earliest known history painting The Mystic Marriage is signed ‘Michaelina Wautier invenit et fecit 1649’. Out of her approximately thirty-five known works, she signed seventeen, always with her full name in italics. Historical catalogues attest to more paintings having once existed but which are now lost. In 1650, dancing master Adam-Pierre de La Grené recorded purchasing a painting, a Bacchus, from her.

M. Wautier’s talent for depicting children is showcased in The Five Senses (1650), where she pioneered the theme as genre scenes with life-size, individual boys. The psychological depth she lends her subjects is evident in works like the Portrait of Martino Martini (1654), also reflecting her Jesuit ties. In her Self-portrait (c. 1650), she sits confidently at the easel. Archduke Leopold Wilhelm collected four of her works, including The Triumph of Bacchus (c. 1655–59), in which she uniquely included her self-portrait as a bacchante. Its size and male nudes led it to be long attributed to a male artist. It is speculated that, thanks to her brother, she could draw live models in private settings. The 1659 inventory of the archducal collection mistakenly referred to her as Magdalena, which recent research revealed to be her older sister, who was not an artist.

M. Wautier’s last known dated work is The Annunciation (1659), and it is unclear if she painted after this. In 1668, she and Charles were living with Magdalena in a house in Brussels, where they remained until their deaths. M. Wautier died in 1689, and was long forgotten until recent research by Katlijne Van der Stighelen, Jahel Sanszalazar and Jeffrey Muller revived interest. Her first monographic exhibition in 2018, followed by shows in Vienna and London in 2025/26, brought her long-overdue recognition.