Focus

The emergence of bourgeois society in the nineteenth century and its quest for social expression made genre scenes and portraiture popular. They took on a new meaning with the success of photography and portraiture at the end of the century. Women artists of the period, kept at a distance from major painting (historical and religious scenes, official portraits and so on), found a means of creative expression in these types of images.

The home and what it is composed of became a source of inspiration that allowed these female observers of the everyday to combine expectations of bourgeois life – being a good mother and wife – with those of being an artist. As such, Sigrid Hjertén (1885-1948), confined to her home where she raised her son, painted outdoor scenes viewed through her window. Artists also used their children as models. During the Old Regime, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842) painted tender portraits of her daughter Julie. Later, Suzanne Valadon (1863-1938) portrayed the young Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955) in his early years, and Claude Batho (1935-1981) assembled pictures of her daughters in the portfolio Portraits d’enfants (1975). Photographers such as Ergy Landau (1896-1967) and Olga Maté (1878-1961) specialised in, and flourished with, children’s portraits. In certain works, the mother would join her child, as in Mother and Child (1939) by Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012).

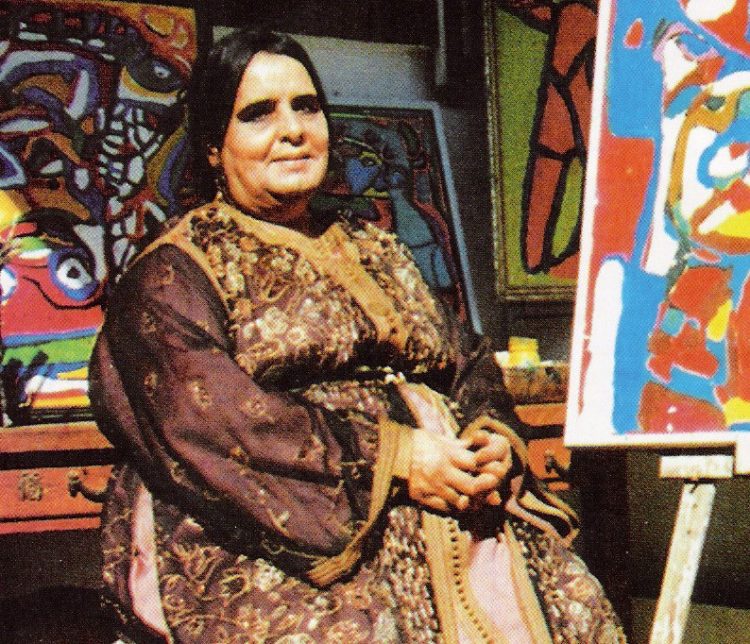

Certain artists are interested in the filial relationship and the way of expressing the loss of a child, which sometimes takes on a morbid approach in the case of Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), or borders on psychosis with Alice Neel (1900-1984). Other female artists observe childhood outside the intimate setting, such as the Swedish painter Siri Derkert (1888-1973), who depicted street children in the despair of their daily lives. After her, photographers Eva Besnyo (1910-2003), Klara Langer (1912-1973) and Helen Levitt (1913-2009) made street children the subjects of their work. The theme of childhood is also a way for artists to find their own moments of innocence. It is this familiar universe that Moroccan artist Chaïbia Talal (1929-2004) tried to reconstruct in some of her paintings.

Everyday life can be found in the work of more contemporary artists who disrupt the traditional genre scene, stripping it of its static characteristic. Mary Kelly (b. 1941) no longer freezes instants of the everyday on a canvas or in a photograph; she uses events such as postpartum period to scrutinise and study it over time. In Mother Tongue (2002), Zineb Sedira (b. 1963) turns a banal scene of a discussion between a mother and her daughter into an analytical tool that transcends generations and materialises cultural boundaries.

While today women artists have taken their practice out of the home, some still find it interesting. However, this should not be considered the only source of inspiration for women artists. In fact, this theme is being called into question and women artists are emancipating themselves from it, sometimes even perverting it, as seen with South African artist Marlène Dumas (b. 1953), who depicts deformed children’s bodies in her paintings.

1885 — 1948 | Sweden

Sigrid Hjertén

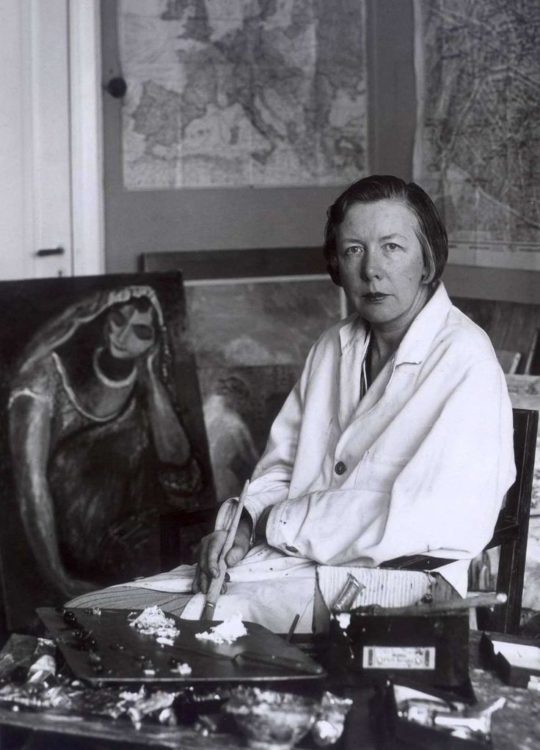

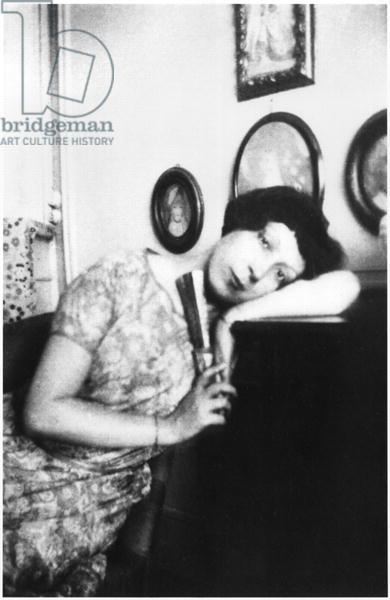

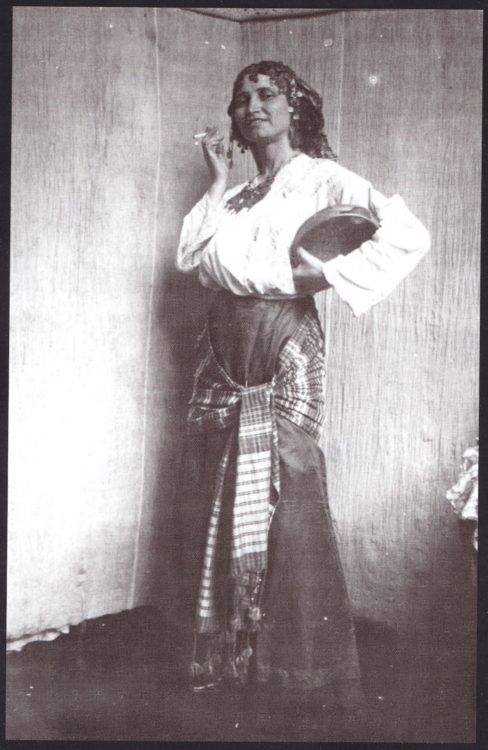

1865 — 1938 | France

Suzanne Valadon

1935 — 1981 | France

Claude Batho

1896 — Hungary | 1967 — France

Ergy Landau

1913 — 2009 | United States

Helen Levitt

1878 — 1961 | Hungary

Olga Máté

1915 — United States | 2012 — Mexico

Elizabeth Catlett

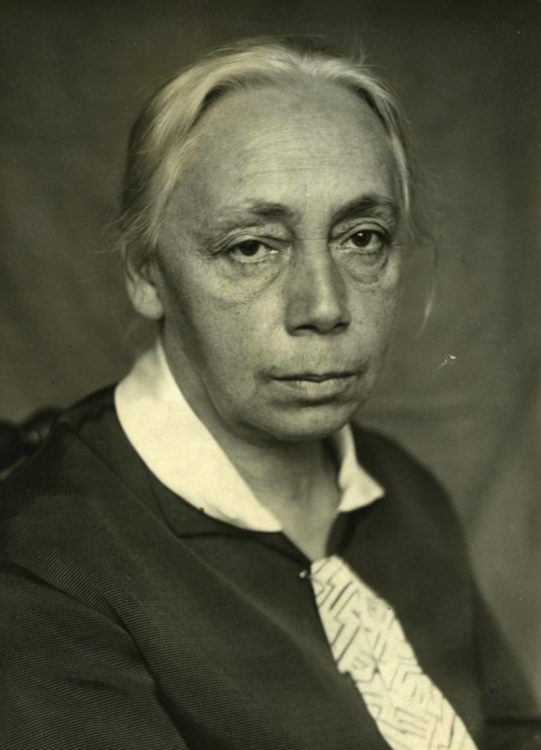

1867 — Russia | 1945 — Germany

Käthe Kollwitz

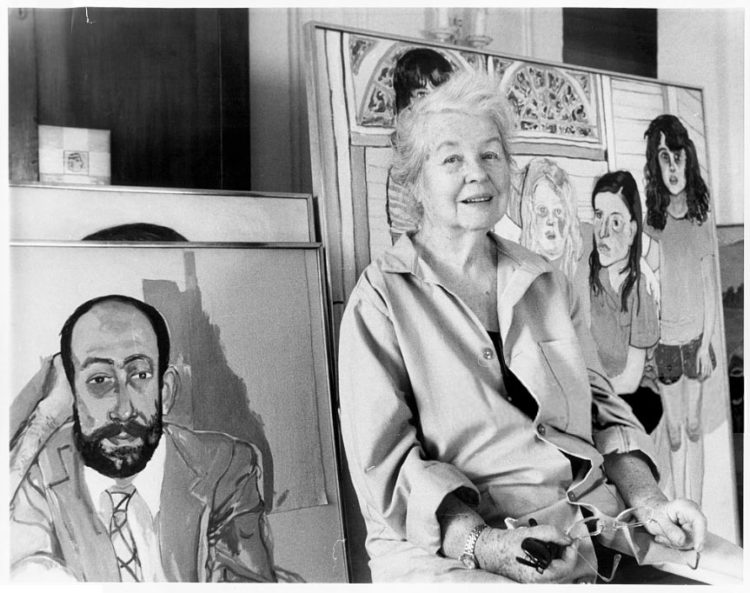

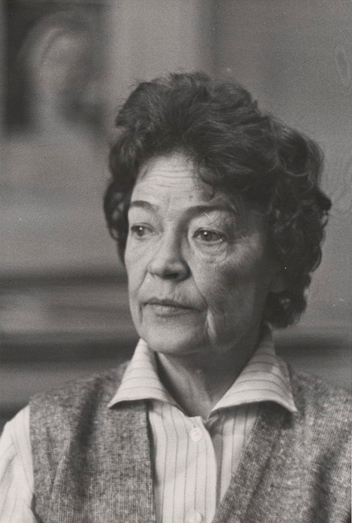

1900 — 1984 | United States

Alice Neel

1888 — 1973 | Sweden

Siri Derkert

1910 — Hungary | 2003 — Netherlands

Eva Besnyő

1912 — 1973 | Hungary

Klára Langer

1929 — 2004 | Morocco

Chaïbia Talal

1941 | United States

Mary Kelly

1963 | France

Zineb Sedira

1953 | South Africa

Marlene Dumas

1950 | Nepal

Shashikala Tiwari

1883 — 1956 | France

Marie Laurencin

1963 | United Kingdom

Gillian Wearing

1911 — 1991 | Hungary

Marian Reismann

1865 — Poland | 1940 — France

Olga Boznańska

1856 — Germany | 1927 — France

Louise Breslau

1858 — Ukraine | 1884 — France

Marie Bashkirtseff

1856 — 1942 | United States

Anna Elizabeth Klumpke

1859 — 1935 | France

Virginie Demont-Breton

1845 — 1928 | France

Madeleine Lemaire (Jeanne Magdelaine Lemaire, dite)

1844 — United States | 1926 — France

Mary Cassatt

1855 — Austria | 1927 — United-Kingdom

Marianne Stokes (née Maria Léopoldine Preindlsberger)

1860 — 1957 | France

Gabrielle Debillemont-Chardon

1939 — 2020 | Algeria

Leila Ferhat

1922 — Germany | 2013 — Israel

Ruth Schloss

1908 — 2004 | Spain

Francis Bartolozzi (Pitti)

1926 — Jamaica | 2018 — United States

Dorothy Henriques-Wells

1875 — 1961 | Bulgaria

Elena Karamihaylova

1908 — Ottoman Empire (today North Macedonia) | 1996 — Bulgaria

Vera Todorova Nedkova

1920 — 2011 | Colombia

Lucy Tejada

1872 — 1937 | France

Jane Atché (dite Jal)

1901 — 1980 | Estonia

Aino Bach

1910 — 1943 | Hungary

Kata Sugár

1948 | Israel

Haya Graetz-Ran

1921 | Paraguay

Olga Blinder

1895 — 1960 | Uruguay

Petrona Viera

1749 — 1808 | Netherlands

Christina Chalon

1732 — 1803 | Netherlands

Sara Troost

1743 — 1813 | Netherlands

Maria Margaretha la Fargue

1969 | United States

Chantal Joffe

1881 — 1965 | Bulgaria

Elisaveta Georgieva Konsulova-Vazova

1741 — Switzerland | 1807 — Italy

Angelica Kauffman

1721 — 1773 | Prussia (now Germany)

Anna Dorothea Therbusch

1874 — 1948 | United States

Fra Broadwell Dinwiddie Dana

1749 — 1803 | France

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

1734 — 1772 | France

Marie-Suzanne Roslin, née Giroust

1552 — 1614 | Italy

Lavinia Fontana

1638 — 1665 | Italy

Elisabetta Sirani

1535 — 1625 | Italy

Sofonisba Anguissola

1883 — 1962 | United States of America

Lora Webb Nichols

1847 — 1917 | Japan

Shohin Noguchi

1911 — Việt Nam | 1988 — France