Annastasia Munyawarara (Anna Mariga)

Joosten, Ben, Sculptors from Zimbabwe: The First Generation, Dodewaard, Netherlands: Galerie de Strang, 2001

→Mariga, Joram, Young Farmers Club, exh. cat., Mutare, Zimbabwe: Umscan, 1981

Young Farmers Club Exhibition, Mutare Gallery, Mutare, Zimbabwe, 1981

Zimbabwean sculptor.

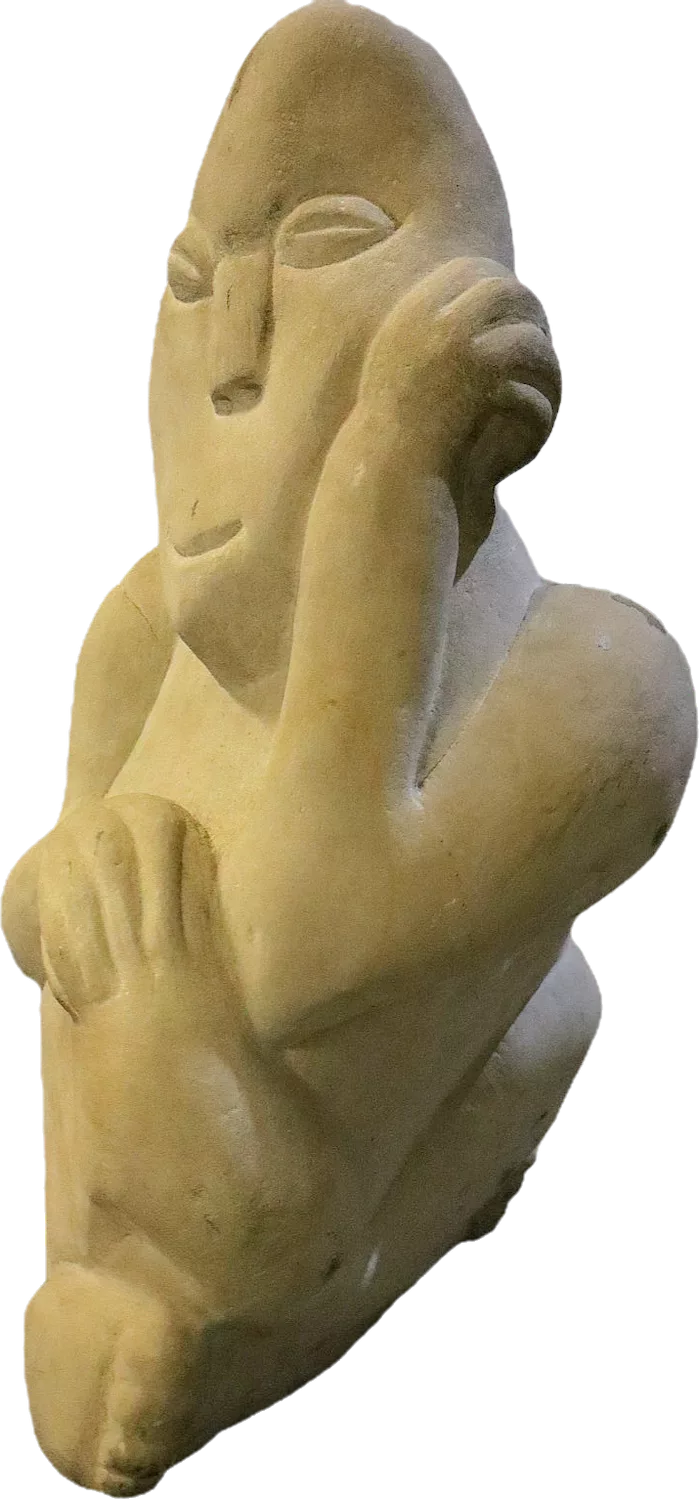

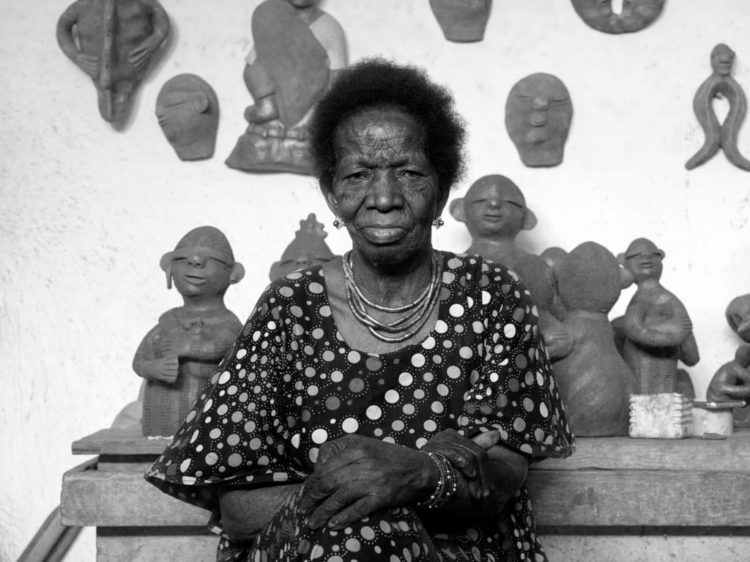

Born on 3 March 1949, Annastasia Munyawarara’s artistic career was relatively brief, yet it left a lasting impression on Zimbabwe’s community of stone sculptors and her own family of artists. Working primarily in sandstone, her figurative sculptures attracted the attention of Frank McEwen (1907–1994), founding director of the Rhodes National Gallery (now the National Gallery of Zimbabwe). F. McEwen’s acquisition of two of her works for the museum in around 1963 marked an early instance of institutional recognition of her talent – remarkable at a time when women artists were largely overlooked, and during a transformative period in Zimbabwean art history, as what came to be marketed internationally as ‘Shona sculpture’ – a colonial and commercial label imposed on a diverse modern movement – was gaining global visibility.

Her artistic path unfolded within a profoundly creative environment: her husband, Joram Mariga (1927–2000), often regarded as the father of Zimbabwean stone sculpture, was both her mentor and a central figure in her development, and several of their five children – Mavis, Walter, Daniel, Aaron and Jay – would later pursue artistic careers of their own. When J. Mariga, then working as an agricultural demonstrator, was posted to Chiredzi (Jack Quinton Bridge), a rural town in southeastern Zimbabwe’s Masvingo Province near the border with Mozambique, A. Munyawarara-Mariga began sculpting to occupy her time in this linguistically and culturally different environment. What began as a modest pastime soon evolved into a serious artistic pursuit, as she refined her technical and creative abilities under her husband’s guidance.

In the 1960s and 1970s, opportunities for women sculptors in Zimbabwe (then known as Rhodesia) were extremely limited. Working with stone – a medium traditionally associated with physical strength and masculine ideals – women artists were rarely recognised or encouraged. Despite these challenges and her separation from J. Mariga, A. Munyawarara persisted. Although she seldom exhibited formally, her work attracted the attention of international collectors and was occasionally included in local showcases. Her sandstone sculptures conveyed a quiet strength and an intuitive sensitivity to form, reflecting both her environment and her lived experience. While A. Munyawarara’s possible association with the Nyatate Group – active in Nyanga between approximately 1962 and 1968 – remains undocumented, it is plausible that she was part of that creative milieu through proximity and shared influence. The group, founded around J. Mariga’s early experiments in stone carving, gathered some of the earliest Zimbabwean modern stone sculptors, including Ndakatsikeyi Manyandure (c.1885–?), one of the few known women in the community. N. Manyandure was remembered as an extraordinary and unconventional figure who began carving late in life, working on her knees and earning the nickname Karambaduku Kamunamuna – “the one who does not wear a head doek, who is like a man”. Like N. Manyandure’s, A. Munyawarara’s persistence and artistic defiance quietly challenged the gendered boundaries of sculpture in mid-20th-century Zimbabwe.

In 1981, the year of one of her few documented gallery exhibitions (Young Farmers Club Exhibition, Mutare Gallery, Mutare, Zimbabwe), A. Munyawarara retired from sculpting to dedicate more time to raising her children. Despite her contributions, A. Munyawarara’s work remains under-documented, reflecting broader archival gaps for women artists of her generation in Zimbabwe.

A biography produced as part of the project Tracing a Decade: Women Artists of the 1960s in Africa, in collaboration with the Njabala Foundation

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025