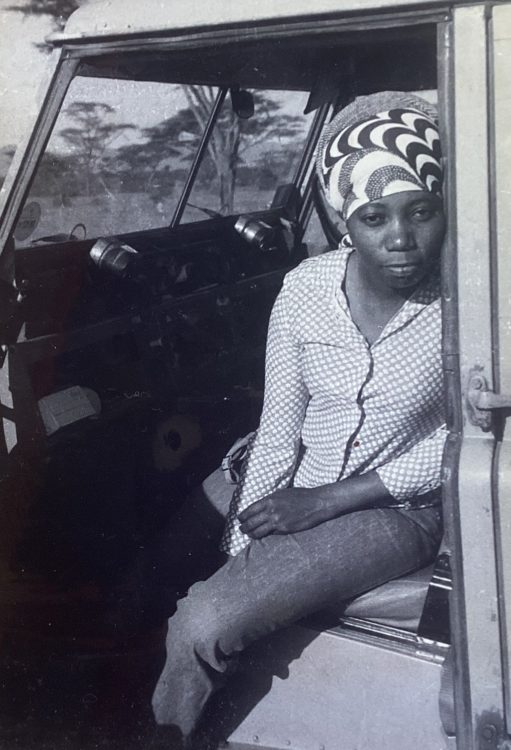

Reinata Sadimba

Underwood, Joseph L. and Okeke-Agulu, Chika, African Artists from 1882 to Now, London, Phaidon, 2021

→Sousa, Souzana and Burluraux, Odile (eds), The Power of My Hands – Africa(s): Women Artists, exh. cat., Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (2021), Paris, Paris Musées, 2021

→Gandolfo, Gianfranco, Reinata Sadimba: We are not equal, we are different, Maputo, Kapicua, 2012

The Power of My Hands – Africa(s): Women Artists, Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris, May–August 2021

→Conexões Afro-Ibero Americanas 2.01, UCCLA and Casa América Latina, Lisbon, February–April 2017

→Lusophonies, Galerie Nationale d’Art, Dakar, November 2010

Mozambian ceramicist.

Reinata Sadimba’s trajectory into ceramics is one of resistance and reinvention. The daughter of farmers, R. Sadimba was born in 1945 in Homba, a village on Mozambique’s Mueda Plateau. As a child, she moved to the village of Nimu, in the province of Cabo Delgado, where she received a traditional Makonde education. The Makonde are a Bantu ethnic group spread across northern Mozambique (the Mueda Plateau and Muidumbe), Kenya and Southeast Tanzania. At a young age, R. Sadimba learned to make utilitarian objects from clay, such as pots, plates and pitchers. Although the Makonde assign a predominant role in society to women – they are a matrilineal society, where children and inheritances belong to women, and husbands move into the village of their wives – sculpting is still a male task.

During the Mozambique liberation war in the 1960s, R. Sadimba met a guerrilla fighter who would become her second husband, with whom she had children. At that time, she also joined Frelimo – Frente de Libertação de Moçambique – and worked transporting war material and producing clay pots needed for military life. Within the first years of the country’s independence, she had a second divorce, seven of her children died, and she was left with her youngest and only surviving son, Samuel. This period, from 1977, was crucial for her artistic development, which evolved from utilitarian pieces to sculptures, adding a more complex formal and surface treatment in her ceramics. This meant R. Sadimba had taken on a role previously reserved for male sculptors, causing tensions within her community.

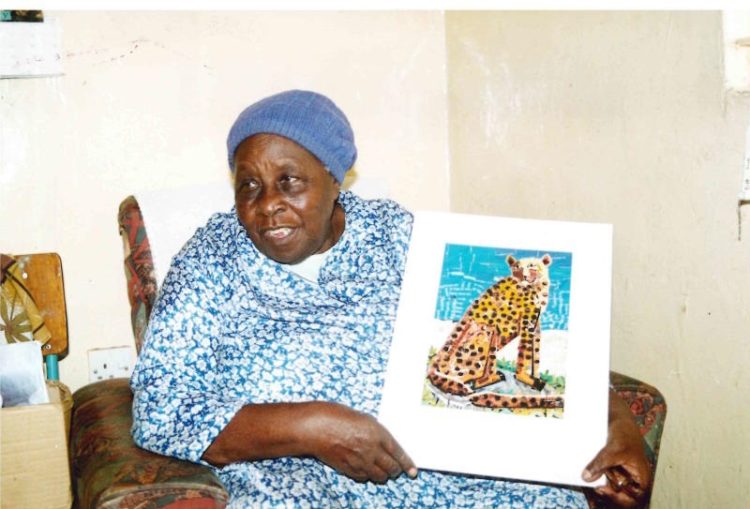

In the 1980s, she befriended Maja Zürcher (1945–1997), a Swiss artist who spent time in Cabo Delgado, working with sculptors in a cooperative in Mueda. They worked together in the village of Nimu. Along with M. Zürcher, R. Sadimba also worked in a later workshop with artists Matias Ntundo (1948-) and Casme Tangawizi (dates?) from Nandimba cooperative, earning her the respect and admiration of her peers for her creativity and skill. R. Sadimba’s technique is simple; she works only with her hands and with very few instruments – a corn cob, a small knife and a saw. In her sculpture work, she references the Makonde tattooing tradition and facial scarification. Her complex anthropomorphic figures have expressive facial features and reflect the Makonde matrilineal universe.

Spending time in exile in Tanzania during a period of political instability in Mozambique, R. Sadimba only returned to Maputo in 1992, by invitation of the Prime Minister Pascoal Mocumbi and with support from Agusto Campos, the director of the Natural History Museum, who gave her studio space where she could work. In 1989, through some of her Swiss friends, Michel Thévoz, director of the Collection de l’Art Brut (Lausanne), decided to acquire three pieces by the artist. She also held her first individual exhibition in the Nyumba Ya Sanaa Gallery in Dar es Salaam.

In Maputo, she continued to exhibit, asserting herself on the local and international art scene. R. Sadimba is a prolific artist and has featured both in contemporary exhibitions and in ethnographic collections. Her work has been displayed mainly in Europe and in Africa and is represented in the National Museum of Mozambique, the Ethnology Museum of Lisbon, and the Tate Modern, from the collection of the late Robert Loder, and in private collections such as Perve Galeria’s LusoPhonies Collection, the Culturgest’s Modern Art Collection and the Sarenco Collection.

A biography produced as part of the project Tracing a Decade: Women Artists of the 1960s in Africa, in collaboration with the Njabala Foundation

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2024