Review

Wura-Natasha Ogunji, Will I still carry water when I am a dead woman?, 2013, video, 11 min. 57 s. © Wura-Natasha OGUNJI / Photo Ema Edosio © ADAGP, Paris, 2020

Within the framework of African Women Focus, part of Africa2020, exhibition curators Suzana Sousa (Angola) and Odile Burluraux (France) invited sixteen African and Afro-descendant artists to leave their mark on the galleries devoted to the permanent collections of the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. Following the long months of confinement imposed by the pandemic, the exhibition The Power of My Hands is now finally at liberty to unveil its brilliant overview of artworks from English- and Portuguese-speaking Africa, whose artists, regardless of sex, are far less visible in metropolitan France than their French-speaking counterparts.

Lebohang Kganye, Setupung sa kwana hae II, 2013, inkjet print on cotton rag paper, 42 × 29.7 cm © Lebohang Kganye. Courtesy AFRONOVA Gallery, Johannesburg © ADAGP, Paris, 2020

The three-part exhibition layout – “Personal Histories”, “Tales and Fictions” and “The Personal is Political” – retraces the unique way in which these women from the African continent itself and from its diasporas have embraced social issues as a means of attaining emancipation and empowerment. United by the same driving force, each of these women seeks to share her personal history as the stepping-stone to a universal dimension. In this way, by means of their own specific artistic medium (painting, photography, video, pottery, installations, etc.) they are bringing about a new visibility in the social perception of Black women and in the heroic burden of care these women have shouldered, particularly in the patriarchal and colonial context 1.

The exhibition opens with the Stolen Moments and Morning Glory (2017), silk tapestries embroidered by Billie Zangewa (b. 1973). These familiar symbols of the burgeoning iconographies encapsulated by Black Joy, Black Self-Love2 and Black Rest depict various scenes from the artist’s daily domestic life. Through her, the well-being of Black women becomes a subject in its own right, an uncharted continent in the history of art which must be conquered. The figures of utter abnegation embodied by these black bodies gradually give way to more pacified images, the icons of Treat Yo’Self.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Predecessors, 2013, charcoal, acrylic paint, graphite and transfer print on paper. Diptych, each panel: 213.4 × 213.4 cm © Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Courtesy of the artist, Victoria Miro and David Zwirner Collection Tate / Photo Sylvain Deleu © ADAGP, Paris, 2020

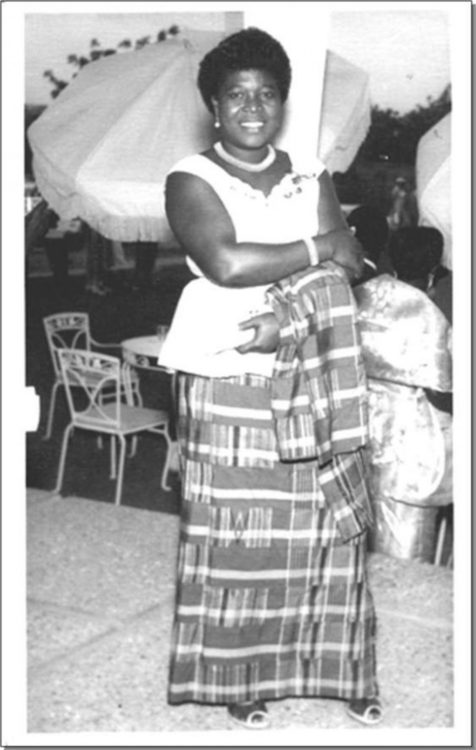

The first section of the exhibition, “Personal Histories”, collates works stemming from archives and recollections initially transmitted through filiation and then reappropriated by the artists. The mother-daughter relationship is the main source of research: what does it mean to be the daughter of an African woman? To be her natural heir(ess)? A mirage, a fusion? How is one “nourished” by one’s mother, on a literal and creative level?

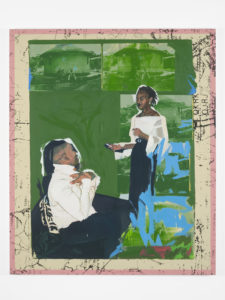

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Newtown, 2019, oil on canvas, 180 × 120 cm, private collection, London, UK © Kudzanai-Violet Hwami / Photo Andy Keate © ADAGP, Paris, 2020

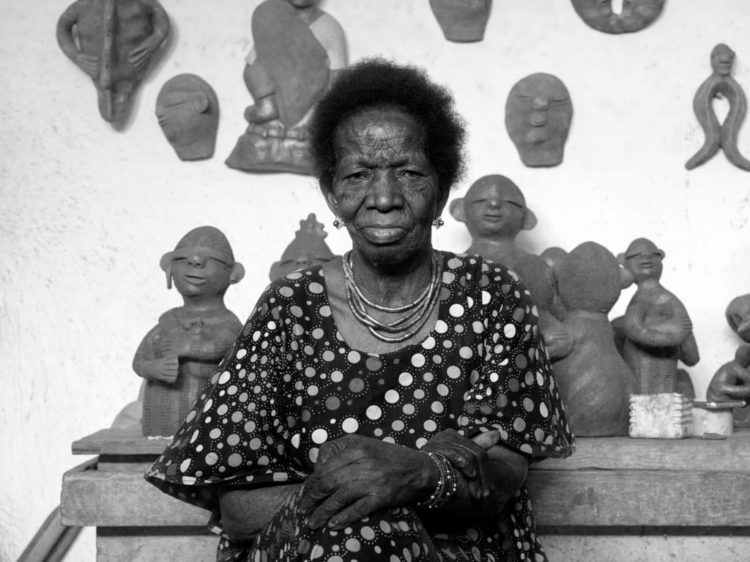

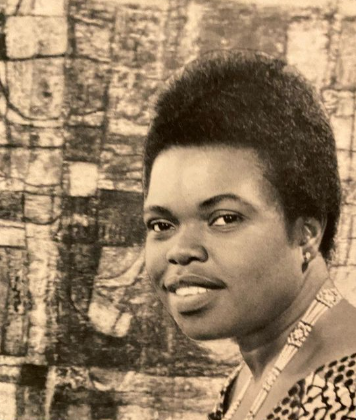

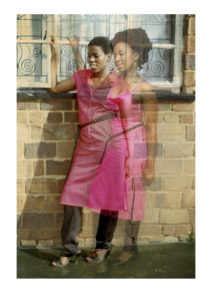

The second facet, “Tales and Fictions”, draws the audience into a series of initiatory and spiritual journeys launched by four artists: Senzeni Marasela (b. 1977), Portia Zvavahera (b. 1985), Grace Ndiritu (b. 1982) and Kudzanai-Violet Hwami (b. 1993). The latter has two canvases on show, including Speaking in Tongues (2019), a strikingly original creation based on optical tricks and distortions. Taking old family photographs from the 1970s as her starting point, K.-V. Hwami devises painted collages, linking them to reproductions of works from the Shona sculpture movement (a contemporary art movement from Zimbabwe) or to symbolic illustrations of local flora and fauna. These haunting infrared, nocturnal green, sepia and ultraviolet images are woven into a mosaic melding the artist’s past, present and future.

Keyezua, The Power of My Hands, 2015, synthetic hair braids, 200 × 360 cm © Keyezua. Courtesy MOVART Gallery, Luanda, Angola / Photo Keyezua © ADAGP, Paris, 2020

The name of the third part of the exhibition, “The Personal is Political”, harks back to the slogan brandished by Western women’s lib movements in the 1960s and 1970s and later widely used in the seminal essays of the Afro-Feminists.3 Its substance is authentically encapsulated in the work of Angolan artist Keyezua (b. 1988) which gave its title to the exhibition. The Power of My Hands (2015) embraces two large works made up of a braided mesh of synthetic hair. In Africa and the “Black worlds” you can actually discover a genuine, ultra-sophisticated and standardised history of hair arts; in the colonial and plantation context, however, Black women’s hair acted both as a tool and as a visible sign of domination. Today this dichotomy has become a template for open wounds but also for creative renewal. Braiding is only carried out manually; it is therefore a particularly lengthy, repetitive and ultimately reflective process – and the contemplation of Keyezua’s work envelops us in the same meditative aura as the women braiding and those being braided. And by their side, we in turn wonder what to do with ourselves. With our denied, caricatured, reviled femininity. What should we be making of this inheritance today? Of the appalling geopolitics of women – a sisterhood of blood, sweat and tears that entails shaving the whole of Asia just so that Africa can adopt a European hairstyle? And what should we be doing with our hands? How can we let them run riot in a world in which Angela Davis continues to hone her Afro hairstyle while at the same time in Brazil hundreds of household sponges are being sold every day under the name “Krespinha” [kinky hair] by the brand Bombril4, a pejorative – and nevertheless widely used – term applied to Black hair?

Ode to the power of African and Afro-descendant women, with their raised palms or two fists. Ode to the power of those hands. “Justice can be done to African women artists,”5 you find yourself saying, quoting the words of Suzana Sousa, co-curator of the exhibition. And for once, in the surroundings of the Musée d’Art Moderne, you cannot help believing that justice has indeed been done.

The Power of My Hands: Africa(s): Women Artists, from 19 May 2021 to 22 August 2021, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, France.

Featuring works by Stacey Gillian Abe, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Gabrielle Goliath, Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, Keyezua, Lebohang Kganye, Kapwani Kiwanga, Senzeni Marasela, Grace Ndiritu, Wura-Natasha Ogunji (and The Treehouse), Reinata Sadimba, Lerato Shadi, Ana Silva, Buhlebezwe Siwani, Billie Zangewa and Portia Zvavahera.

To explore the concept of care in greater detail, see the article by Francesca Scrinzi in Encyclopédie critique du genre, ed. Juliette Rennes (Paris: La Découverte, 2021), pp. 106-115. See also, Manke Kara, “How the ‘Strong Black Woman’ Identity Both Helps and Hurts”, Berkeley News, 5 December 2019: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_the_strong_black_woman_identity_both_helps_and_hurts, accessed 14 June 2021. Kara writes: “The superwoman schema includes five elements: feeling an obligation to present an image of strength, feeling an obligation to suppress emotions, resistance to being vulnerable, a drive to succeed despite limited resources, and feeling an obligation to help others.”

2

Artist Billie Zangewa – The Ultimate Act of Resistance is Self-Love, video created by Tate Modern, London, 2020: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/billie-zangewa-27102/billie-zangewa-ultimate-act-resistance-self-love, accessed 14 June 2021.

3

The slogan “The Personal is Political” as seen by Afro-Feminist essayists: The Combahee River Collective, “A Black Feminist Statement”, in Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Social Feminism, ed. Zillah Eisenstein (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1979), pp. 362-372; Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”, in This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, Gloria E. Anzaldúa and Cherríe Moraga (Watertown: Persephone Press, 1981), pp. 121-125.

4

“Washing the Dishes with Her Afro-Textured Hair: Aesthetic Innovation in the Performance Bombril by Priscila Rezende. In conversation with Ana Abril”, Museum of Equality and Difference (MOED), 18 January 2019, https://moed.online/washing-dishes-with-afro-textured-hair-bombril-priscila-rezende, accessed 14 June 2021.

5

Paris Musées: Expert Talk podcast, “The Power of My Hands – Interview with Suzana Sousa”, 2021, https://soundcloud.com/paris-musees/mam-expert-talk-the-power-of-my-hands-8-questions-to-suzana-sousa?in=paris-musees/sets/mam-paroles-dexperts-the-power, accessed 14 June 2021.

Louise Thurin, "The Power of My Hands – Palms and Fists Raised." In , . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/the-power-of-my-hands-les-paumes-et-poings-leves/. Accessed 5 July 2025