Anne Dangar

Adams Bruce, Rustic Cubism: Anne Dangar and the Art Colony at Moly-Sabata, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2004

→Anne Dangar, céramiste : le cubisme au quotidien, cat. exh., Musée de Valence art et archéologie, Valence (26 June 2016 – 26 February 2017), Paris, Lien Art ; Valence, Musée de Valence art et archéologie, 2016

→Butcher David, Anne Dangar, céramiste, Paris, Lienart, 2016

Anne Dangar at Moly-Sabata: Tradition and Innovation, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 13 July – 28 October 2001

→Anne Dangar, céramiste. Le cubisme au quotidien, Musée de Valence art et archéologie, Valence, 26 June 2016 – 26 February 2017

Australian/French potter, painter, teacher.

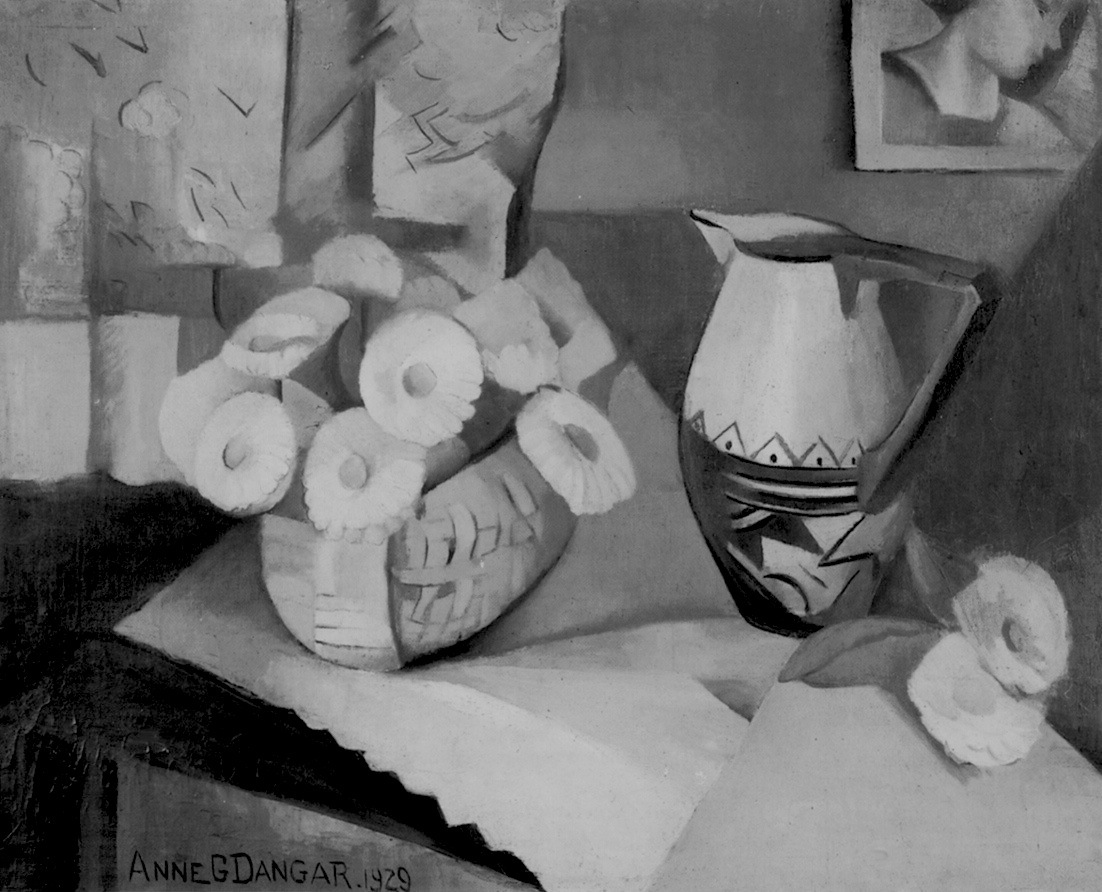

After her academic art training in 1914-20 at Julian Ashton’s Sydney Art School in Sydney, where she also taught between 1920 and 1925, Anne Dangar travelled to France in early 1926 with her close friend, the painter Grace Crowley. In Paris the women commenced private lessons with Beaux-Arts painter Louis Roger, and Dangar also took pottery classes with Henri Bernier in Viroflay, before discovering the work of Cubist painter and critic André Lhote. With Crowley and another Australian, Dorrit Black, Dangar attended the Académie Lhote in Montparnasse in 1927-28 and joined Lhote’s 1928 summer school in landscape painting at Mirmande, la Drôme. Like her companions, she fully adopted Lhote’s analysis of form, firmly delineating the pictorial elements within the flattened space of her compositions. Back in Sydney in 1929, Dangar launched a small independent school in her studio at 12 Bridge Street, where her Lhote-based lessons were exemplified in her Untitled still life of that year. But upon reading La peinture et ses lois, a treatise published in 1924 by the Cubist painter Albert Gleizes, she felt challenged by his ideas and asked Crowley and Black to seek more information. They made contact with Gleizes in Paris and had lessons with him, prompting a quick decision by Dangar to return to France to work under him. In early 1930 Dangar joined the artists’ colony of Moly-Sabata, which Gleizes had founded in 1927 in a historical building alongside the Rhône River in Sablons, Isère. Moly-Sabata was an ideological experiment by Gleizes. He wanted city-trained artists to rediscover la terre and work self-sufficiently towards a cultural renewal based on the revitalisation of agrarian and artisanal practices. After helping the first Moly-Sabatan, Robert Pouyaud, on the production of pochoirs based on Gleizes’ Cubist compositions, Dangar set about learning the traditional skills of local village pottery, firstly at the Poterie Clovis Nicolas, in St Désirat, Ardèche, in 1930-31, and from 1932 under Jean-Marie Paquaud at the Poterie Bert, Roussillon, Isère. She also became an active art and craft teacher to the local village children.

Stoic and self-sacrificing in character, Dangar kept Moly-Sabata going over many difficult years with the help of the younger weaver Lucie Deveyle. Despite much material hardship, especially during the war, she upheld its communal values, remaining a passionate advocate of Gleizes’ philosophies of art, religion and society until her death there in 1951. Dangar achieved acclaim in France for the vitality of her distinctive glazed earthenware. Her decorated pottery combined Gleizes’ geometric motifs and interest in early Christian and Celtic art with the folk imagery of her region. Best described as rustic Cubism, her style also incorporated non-European influences, including arabesque elements after the French Government invited her to work as an instructor to the potters in Fez, Morocco, in 1939. Australian Aboriginal art was another keen interest in her final years, when her belief in the universality of sacred traditions also led her to Catholicism. Her late conversion was encouraged by her contact with Dom Angelico Surchamp of the Benedictine monastery of La Pierre-qui-Vire, Bourgogne. Although she never returned to Australia, Dangar remained a direct influence on modernist art and teaching there through her many letters to her female colleagues, notably Crowley and Black. Her letters also had a lasting impact in France, influencing younger women potters like Jacqueline Lerat in La Borne, and Geneviève de Cissey, who later followed in her footsteps at Moly-Sabata. Her personal writings, like her pottery and the ascetic pattern of her life, were vivid testaments to a woman still revered for her deeply felt attachment to the art and regional culture she adopted in France.

© 2017 Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Anne Dangar, céramiste (1885-1951). Le cubisme au quotidien.

Anne Dangar, céramiste (1885-1951). Le cubisme au quotidien.