Béatrice Casadesus

Casadesus Béatrice (ed.), Le regard et la trace, 1975-2002, exh. cat., Maison des arts de Malakoff ; Musée de Soissons-Arsenal, Soissons ; Institut français de Barcelone (2002-2003), Soissons, Musée de Soissons, 2002

→Lerat Philippe (ed.), Béatrice Casadesus : dévoilements…, exh. cat., Musée Barrois – Espace Saint-Louis, Bar-le-Duc (14 June– 21 September 2014), Vaux-Bar-le Duc, Musée Barrois, 2014

Faire le point, 1972-1977, Musée de Calais ; Musée de Poitiers, 1977

→Le regard et la trace 1975-2002, La Maison des arts de Malakoff, Malakoff, 16 March – 5 May 2002

→Dévoilements…, Musée Barrois – Espace Saint-Louis, Bar-le-Duc, 14 June – 21 September 2014

French painter.

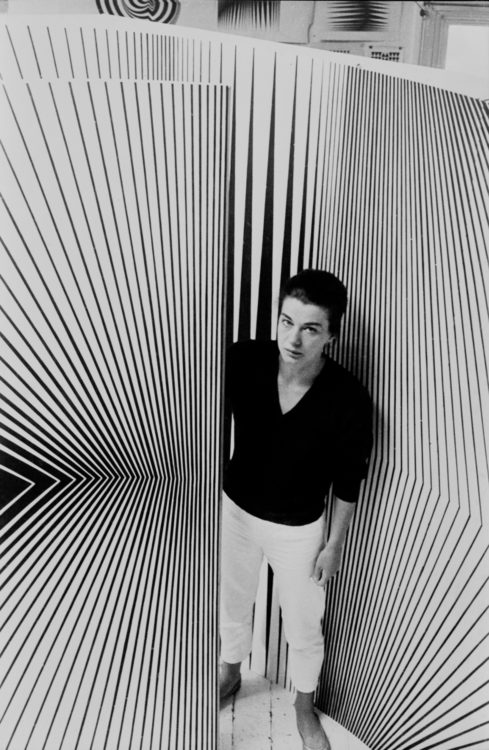

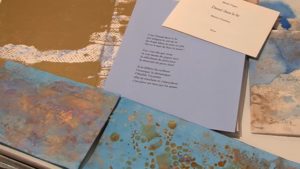

After studying at the School of Fine Arts in Paris, Béatrice Casadesus turned to painting in 1975. Her interest in live performance also led her to participate in the ancient Greek theatre group of the Sorbonne with Jean-Pierre Miquel. She is also a great lover of architecture who has received commissions for public sites and the French Deposits and Consignments Fund (as from 1966), teaches at architecture academies (as from 1968), and regularly collaborates with the architects Antoine Stinco and Christian de Portzamparc (scenery of Grand livre des pas for the École de danse de l’Opéra de Paris, 1986). She works in close collaboration with poets and philosophers (Jean-François Lyotard, Patrice Loraux, Jean-Michel Rey), with whom she has made a great number of single-edition books (1997-2001), thus maintaining the special link between poetry and painting. Her work is grounded in the paintings of the masters that influenced her: Leonardo da Vinci, Masaccio, Seurat, and Malevich.

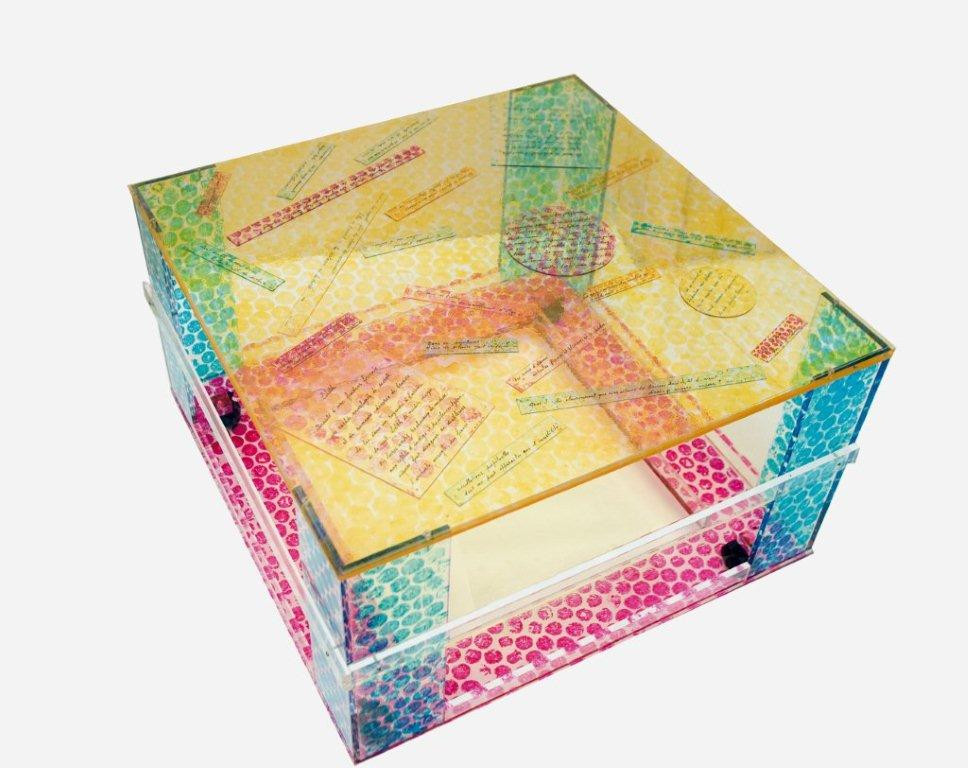

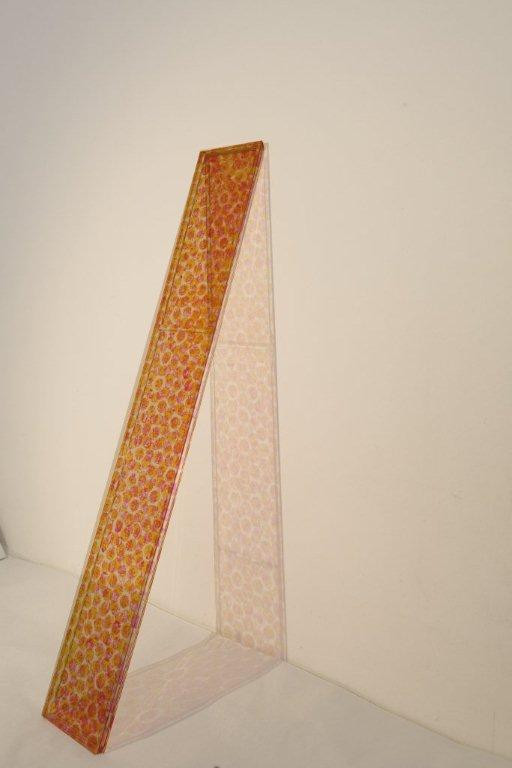

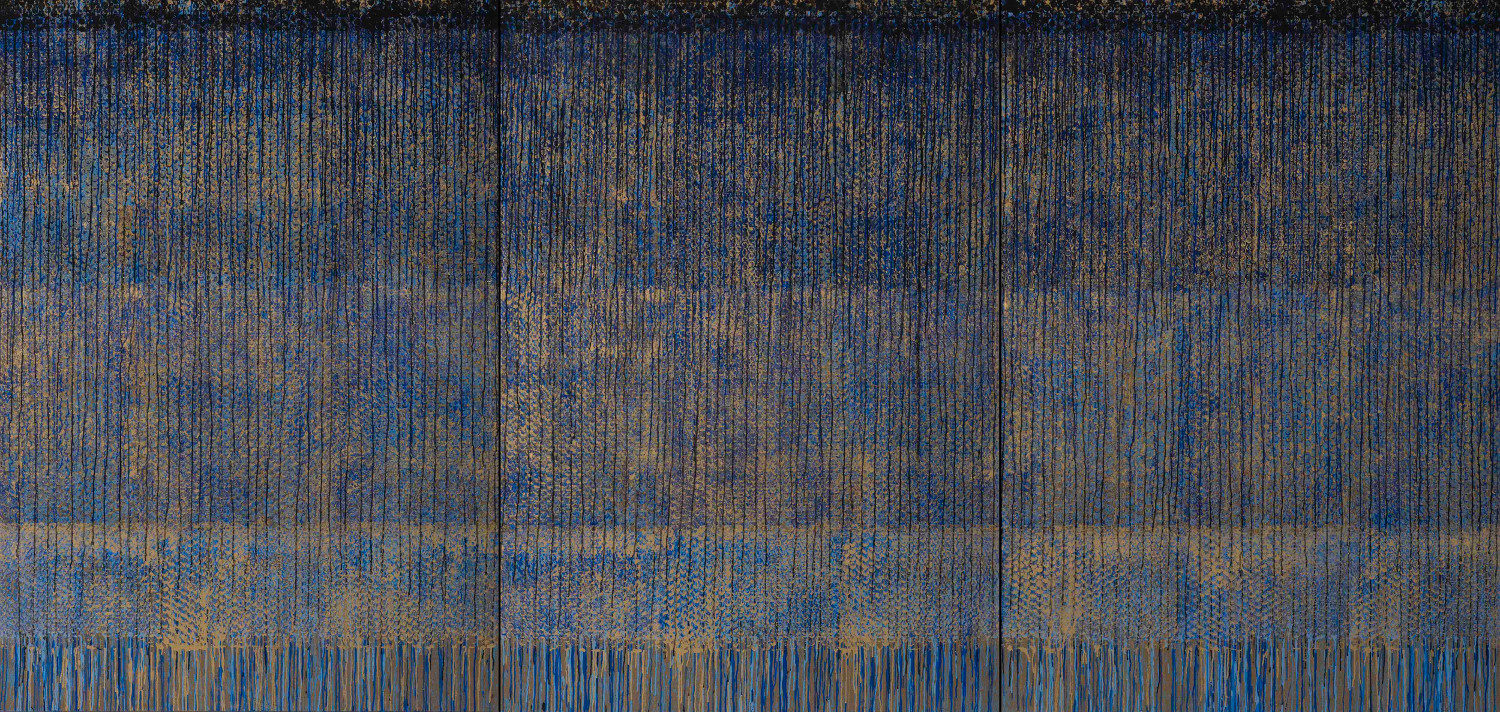

Her research focuses on the dot – a subject that is still relevant –, the outline, and the vibration of light. “My fascination for the movement of specks of light filtering through the leaves led me to look for plastic ways to convey the sensations of nature,” she explains. She seeks to capture the threshold at which an image appears and disappears (Suaire d’otages [Hostage shroud], 1990-1995). A rejection of the artist’s touch and a repetition of the tool-enhanced movement are the creative conditions of a work that exalts absence, not to say dullness. Like the traditional Chinese painters she admires, she considers emptiness to be an absolute. In order to attain this effect, she makes “painting tools” that imprint a trace on the canvas, while the eye of the viewer, depending on the density of the dots, reconstitutes them as a retinal image. The faded colours she often uses must be akin to “passing colours,” be it on the medium itself or in the eye of the viewer. Therefore, some materials, such as rolled canvases (Peintures sans fin [Endless Paintings], 1997-1999) and round crumpled paintings (Mues [Sloughs], 1997-2001), are deliberately made to be translucent and reversible. The results of this creative process, which attempts to keep the artist’s subjectivity at bay, are paintings that keep viewers in a state of weightlessness. Her recent exhibitions (2010) at the Arsenal in Soissons (Aisne) and at the Royal Monastery in Brou (Bourg-en-Bresse), for which she created very large pieces, demonstrate her attachment to history.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Interview of Béatrice Casadesus

Interview of Béatrice Casadesus  Exhibition Dévoilements...

Exhibition Dévoilements...  Béatrice Casadesus in Abbatiale in Essômes

Béatrice Casadesus in Abbatiale in Essômes  Peindre n'est peut-être que traverser la lumière

Peindre n'est peut-être que traverser la lumière