Bridget Riley

Riley Bridget, Moorhouse Paul, Bridget Riley, London, Tate Pub., 2003

→Follin Frances, Enbodied visions: Bridget Riley, op art and the sixties, London, Thames & Hudson, 2004

→Kudielka Robert, Tommasini Alexandra & Naish Natalia, Bridget Riley, the complete paintings, London, New York, Thames & Hudson, 2018

Bridget Riley: works 1959-1978, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 19 January – 2 March 1980

→Bridget Riley : paintings and drawings 1961-2004, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 14 December 2004 – 6 March 2005 ; City Gallery Wellington, Wellington, 23 March – 26 June 2005

→Bridget Riley, Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, 12 June – 14 September 2008

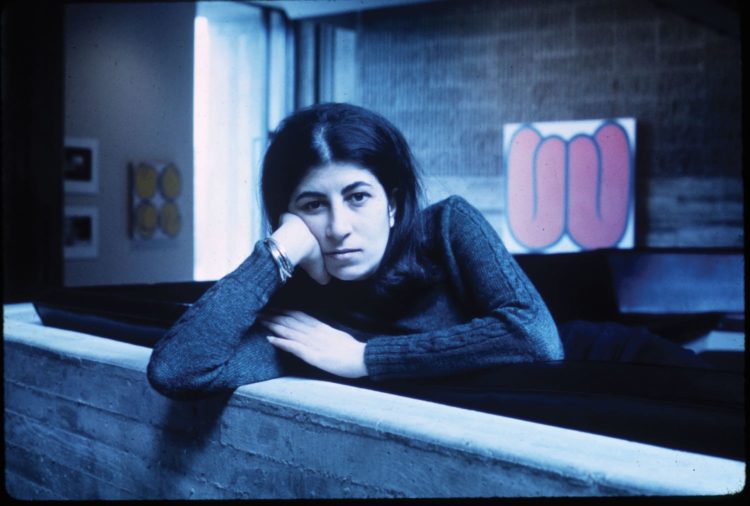

British painter.

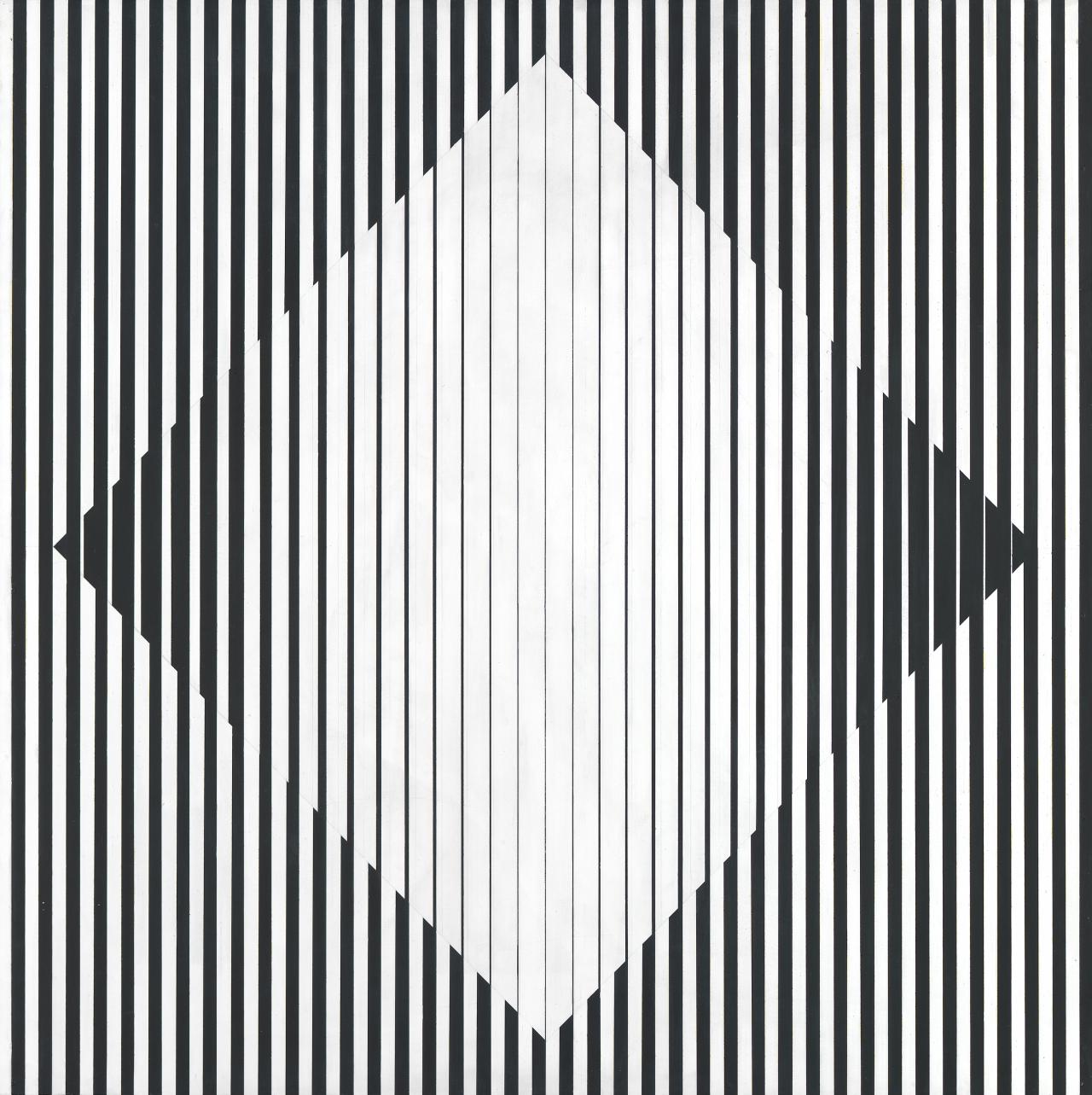

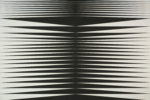

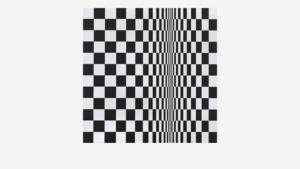

Bridget Riley grew up in a well-to-do family that sought refuge in Padstow, Cornwall, during World War II. Starting in her early childhood, she developed a keen sense of observation and a strong affinity with nature. In 1949, she entered Goldsmiths’ College, University of London, to study drawing with Sam Rabin, before pursuing her education at the Royal College of Art, in London, from 1952 to 1955. She then joined the J. Walter Thompson Group advertising agency, while searching for her own unique path as an artist: during this time, she “abstracted” nature in highly contrasted pencil drawings (Men Lying Down, 1957-1958), and analysed the methods of divisionism by copying Seurat’s Le Pont de Courbevoie. During summer courses organized by Harry Thubron in 1959, she met painter Maurice de Sausmarez, who became her mentor, introducing her to futurism, divisionism, and the roots of modern art. She returned from a trip to Italy with landscapes displaying intense colours, animated by visible brush strokes (Pink Landscape, 1960). Falling prey to a personal and artistic breakdown in the autumn of 1960, Riley created her first black and white painting, Kiss, in a geometric style not unlike hard-edge painting. The same year, she met painter Peter Sedgley, with whom, ten years later, she would create SPACE, an organization offering low-cost workshops. In 1961, she began to focus on her black and white paintings, in which the perception of stable elements (format, form, and colour) is disrupted by different compositional processes, which, superimposed, cancel each other out and dissolve (Movement in Square, 1961). Her first solo exhibition at Gallery One in London in 1962 attracted the attention of critics. In 1965, William Seitz invited her to participate in The Responsive Eye, an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York. Quite receptive to European art, this event, which was meant to show the latest trends in abstract art, quickly entered the visual landscape of the world of fashion: the motifs of Op Art began to fill storefronts. This was, however, a double-edged success for Riley, who, fearing the loss of her artistic credibility, insisted on suing the stores in question for copyright infringement, with the help of painter Barnett Newman’s lawyer.

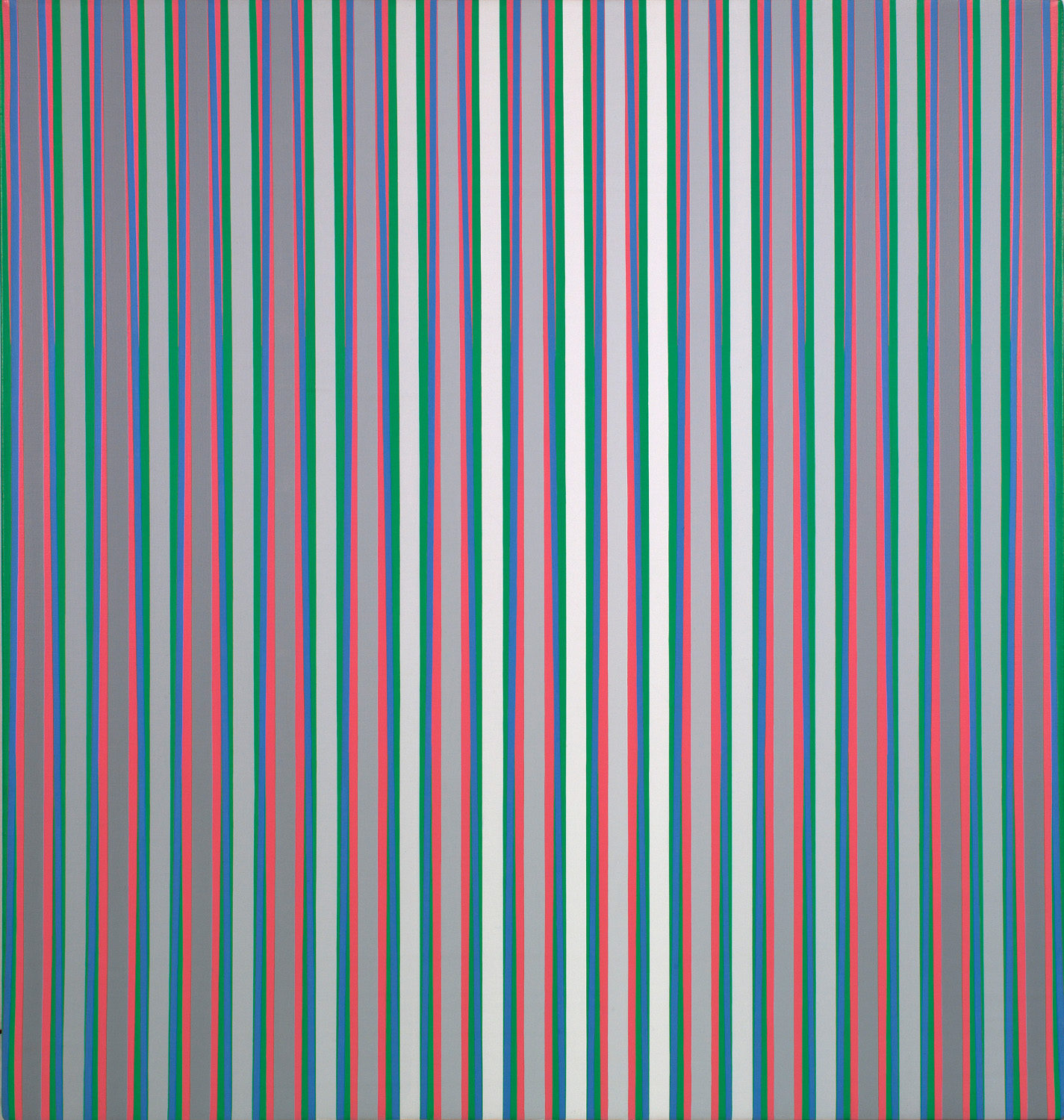

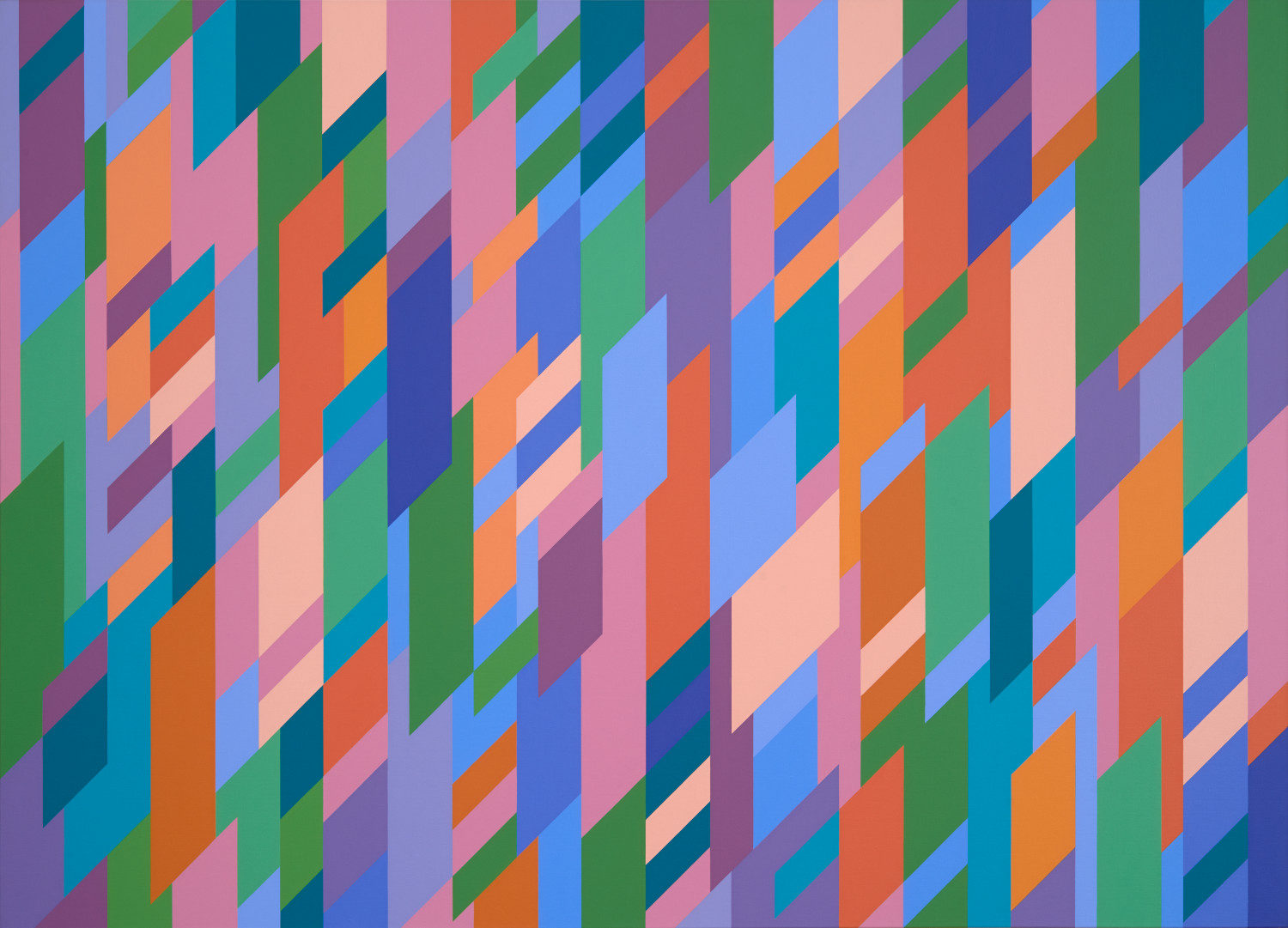

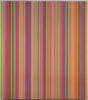

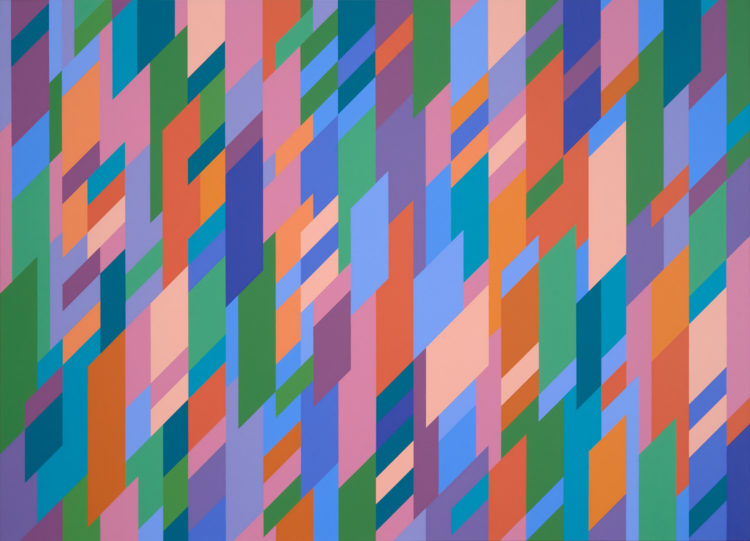

In the late 1960s, her paintings began to be produced by assistants, herself having previously studied their composition in many drawings. During the same period, she expanded her palette to include warm and cold shades of grey, as well as other colours. The inclusion of pure colours introduced an additional level of instability in in the visual perception of the viewer (Cataract 3, 1967), leading her to limit her pictorial process to straight lines and the interaction of two or three colours (Late Morning, 1967-1968). In 1968, she became the first woman and the first contemporary British painter to win the Venice Biennale Grand Prize for painting. Her interest in German, Spanish, and Baroque art, rekindled during her travels with Robert Kudielka, pushed her to further diversify her shapes and colours – braids, curved lines, and pastel hues – and to evolve towards a more lyrical style (Clepsydra 1, 1976). During a trip to Egypt in 1979, she discovered a specific palette (turquoise, blue, yellow, green, black, and white) she would use upon her return in a series of oil paintings. She once again used colourful vertical strips, grouped more liberally according to the feelings they conveyed, as well as their spatial characteristics (Serenissima, 1982). In the mid-1980s, the introduction of dynamic diagonals transformed the vertical structure that had defined the Serenissima series thus far. These paintings, which began to sport diamond shapes, lead the eye in a circular motion, pushing the artist to return to curvilinear forms in 1997. Her large-scale paintings featuring large swathes of colour (such as Parade 2, 2002) recall Matisse’s work. In 1998, Riley created her first mural drawing: a composition made up of black circles on a white background, providing the viewer with contradictory sensations of movement and depth. As of 2007, she would also design several mural paintings that revisited the shapes featured in her contemporary paintings, by extending them beyond the frame. Since 1971, her body of work has been featured in many international retrospectives, and was rewarded in 2009 with the prestigious Kaiser Ring prize from the city of Goslar.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Paroles d'artistes : Bridget Riley

Paroles d'artistes : Bridget Riley  Works in Focus: Bridget Riley

Works in Focus: Bridget Riley