Research

Hotham Street Ladies (Cassandra Chilton, Molly O’Shaunessy, Sarah Parkes and Caroline Price), Unbridled Abundance: Pink Bits ‘n’ Saggy Tits, 2020-2021, royal icing, food colouring, aluminium, mesh, canvas, MDF © Courtesy Hotham Street Ladies

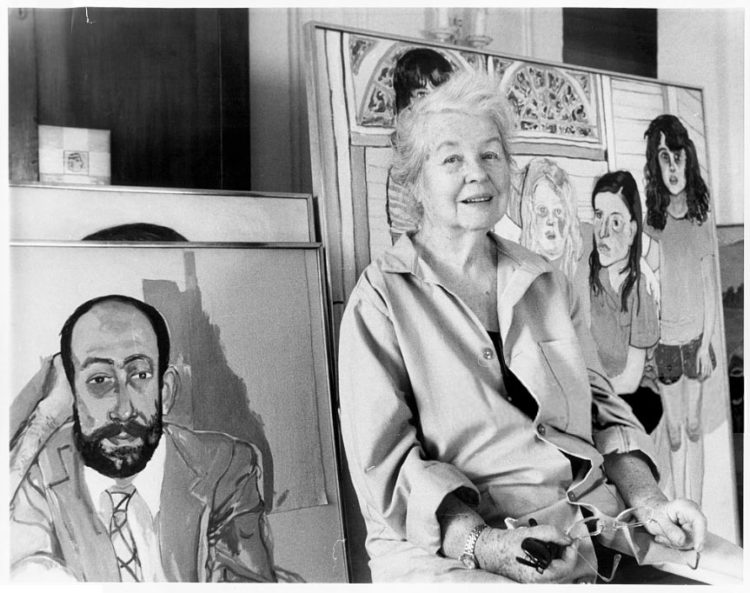

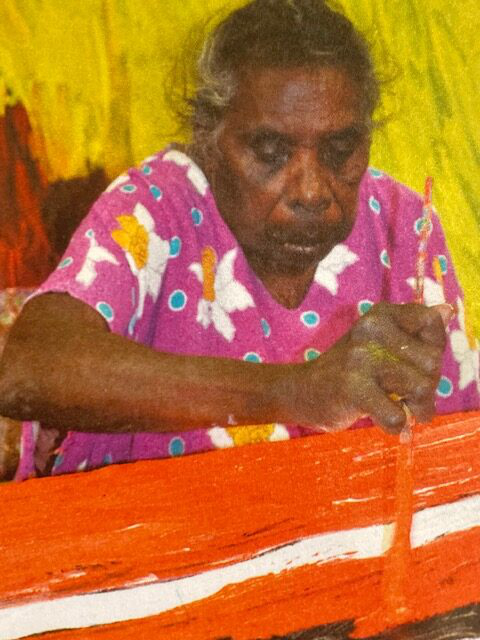

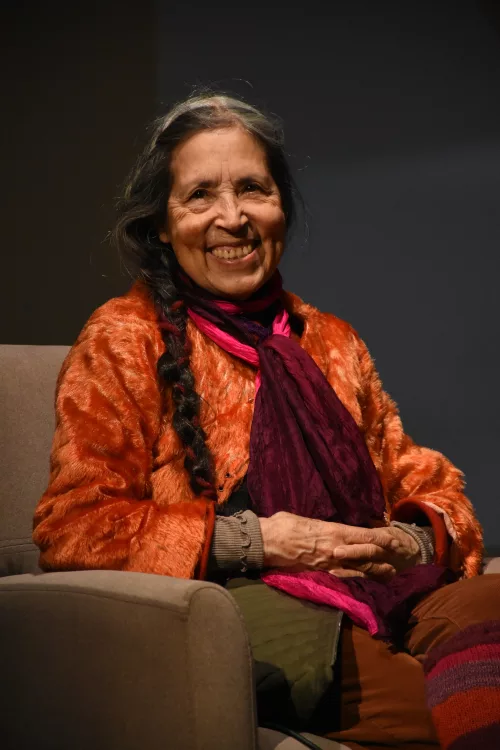

There might be a noticeable spike in the incidence of major exhibitions and commissions of work by older women – think Cecilia Vicuña and Joan Jonas, current examples of the broader phenomenon of belated institutional recognition for the significant contribution to contemporary art by figures such as Alice Neel, Louise Bourgeois, Bridget Riley, Paula Rego, Ana Maria Pacheco, Sally Gabori and Barbara Hepworth among others. But this does not, however, equate with a surge in artistic engagement with ageing. Indeed, art historian Michelle Meagher’s 2019 assessment that “within the field of art, age and ageing are surprisingly underexplored” still rings sadly true.1 But might this be changing?2 This article considers why the process of women’s ageing remains a difficult subject, touches on some art historical precedents and considers examples of current practice (focused on Australia) which hope to expand understandings of the experience of ageing and perceptions of the older female body.

Shame and abjection

The invisibility of older women, the gendered shame attached to ageing and the disconnect between the lived experience of getting older and its visual representations remain topical issues. How is it that the process of a woman’s ageing, which should attest to her fortitude and good health, has come to represent one of society’s ultimate abjections? Writing in 1913 on obsessional neurosis, Sigmund Freud summarised western culture’s stereotype of the ageing woman:

[…] it is well known and a matter for much complaint that women alter strangely in character after they have abandoned their genital functions. They become quarrelsome, peevish and argumentative, petty and miserly […] traits which were not theirs in the era of womanliness.3

Characterised as a problem, the unwomanly behaviour of the post-menopausal woman has come to legitimise the social ostracism she suffers, a legitimacy that relies on the pervasive internalisation of this stereotype and the shame that then keeps women from asserting their full subjectivity. American feminist film scholar Vivian C. Sobchack nailed this shame, linking her personal experience of ageing with a compelling theory of what’s at stake in low-budget monstrous female horror films:

The older woman […] evokes in herself and in others the horror and fear of an inappropriate and transgressive sexual desire that lingers through the very process of ageing, physical degradation and decay […] Objectively viewed, she is ludicrous, grotesque […] and abjectly needy; or she is angry, vengeful, powerful, scary. Subjectively felt, she is an excess woman, desperately afraid of invisibility, uselessness, lovelessness, sexual and social isolation and abandonment, but also deeply furious at both the double standard of ageing in a patriarchal culture and her acquiescence to male heterosexist values and the self-contempt they engender.4

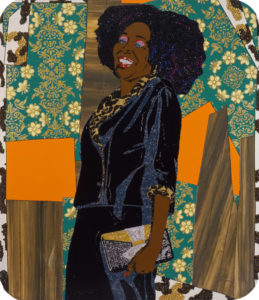

Mickalene Thomas, Mama Bush: (Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher, 2009, rhinestones, acrylic and enamel on wood © ADAGP, Paris 2023

Sally Rees, Flock, 2020, video still © ADAGP, Paris 2023

Sobchack admits that this woman not only scares men, but also horrifies her: gazing in the mirror, she beholds a woman who deceives herself that she is still young, a caricature of desire and desirability, a woman in masquerade.

The body which corresponds to cultural stereotypes of what is feminine is crucial to many women’s sense of self: to exceed the boundaries of the properly feminine through old age may foment a shattering loss of identity, for in many cases, “the body by which a woman feels herself judged is the body of early adolescence, slight and unformed[…], a body in whose very contours the image of immaturity has been inscribed”.5 The visibly ageing body represents a challenge to the self-deluding fantasies of immortality that mark the dominant culture, so that the aged, in particular women, drop out of public space and the domain of the universal into the desolately private and particular. It is rare to encounter images of the naked aged body outside specialised medical discourse, and while the history of western art may in large part be the representation of the human form, old women do not really feature in the pantheon of The Nude: as art historian Griselda Pollock quips, older women are not absent from art history, it’s just that they figure “in ways that sustain a cultural fascination with youthful femininity’, primarily as hags and crones”.6

After what amounts to forced exclusion from the sexual economy and public agency, to be quarrelsome, peevish and argumentative might be an entirely appropriate response: not the natural consequence of menopause, but a natural reaction to how society regards old age. How has feminist art engaged with one of the last frontiers of discrimination and injustice?

Joan Semmel, Skin in the Game, 2019, oil on canvas in 4 parts, 96 × 288 in. overall (243.84 × 731.52 cm), each 96 × 72 in. (243.8 × 182.9 cm), Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York © 2023 Joan Semmel / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York © ADAGP, Paris

Alternative approaches to ageing

Rather than countering negative stereotypes with positive images,7 feminist art about age and ageing that evokes lived experience as unstable and disorderly – where for example recollections of youth and anticipations of age collide and interact (“transageing”8) – might better contribute to changing the discourse.9 In creating a “counter archive of women and time”,10 such artistic approaches might also mobilise solidarity through the affective registers of humour and sensuality.

Unsurprisingly, American Suzanne Lacy’s innovative social practice has over the years attempted these very things: inclusive exchanges that centre the voices of older women while facilitating solidarity. Projects such as Whisper, the Waves and the Wind (with Sharon Allen, 1983–1984), Crystal Quilt (1985–1987) and its rethought iteration Silver Action (2013), are time-extensive performances and multi-layered pedagogical processes that meld opportunities for personal conversation with public demonstrations of both the felt experience of ageism [discrimination on the basis of age] and the overlooked power of ageing women. Feminist photography, in part in the tradition of Jo Spence’s self-reflexive explorations of socially marked bodies, has also attempted to reframe the ageing female body, including through sensitive renderings of ageing mothers (Melanie Manchot, Mickalene Thomas) or disturbing contrasts of the artist’s own desirable youthful body with the mother’s age-ravaged abject one (Hannah Wilke). Abjection, albeit laced with humour, also distinguishes Miwa Yanagi’s wild evocations of grandmothers living out their fantasies, while the conflicted and fragmentary condition of “transageing” is poignantly captured in Joan Semmel’s more recent paintings.

Ponch Hawkes, Erin Margarett, from the series 500 Strong, 2022, digital print on cotton rag paper © Courtesy Ponch Hawkes

Ponch Hawkes, Genevieve Dedini, from the series 500 Strong, 2022, digital print on cotton rag paper © Courtesy Ponch Hawkes

Ponch Hawkes, Mary O’M, from the series 500 Strong, 2022, digital print on cotton rag paper © Courtesy Ponch Hawkes

In current Australian feminist art, ageing is addressed with playfulness and humour to foment solidarity while asserting a kind of insouciant visibility. Sally Rees’ Crone (2020–2021) is a series of video portraits of older women from the artist’s social network. Enhanced with costumes and prosthetic noses, and overlaid with animation that creates colourful ejaculations each time they call out to each other in the voices of birds, the subjects are transformed into magical beings: knowing, mischievous, powerful and conspiratorial in the best sense. 2021 also saw the culmination of an ambitious multidisciplinary project that foregrounds the relationship between visual cultures and the physical, mental, social and economic wellbeing of older women: Flesh after Fifty, curated by Jane Scott in dialogue with Professor Martha Hickey, whose research at the Melbourne’s Royal Women’s Hospital focuses on the menopause.11 Through newly commissioned and existing work, the exhibition presents a diverse set of ripostes to the exclusion of older women from the public sphere and the sexual economy, ranging from harnessing the rage, embracing the excess, owning the shame and reclaiming the archive to enjoying the body. But above all, the exhibition affirms the importance of solidarity. It asserts that wellbeing is inter-relational rather than achieved by meeting the needs of autonomous individuals. This is best embodied in the project 500 Strong.

For 500 Strong, Ponch Hawkes, a feminist photographer active since the 1970s, recruited nearly 500 women from around the state of Victoria for a private nude portrait sitting; participants were “encouraged to compose their own presentation and determine how identifiable they wish[ed] to be”, and to “bring along a prop or object to hold in front of your face if desired”.12 Once invited into the studio, Hawkes would set the participants at ease with warm conversation, using the prop – be it a lampshade, book, fan, fern frond or scuba mask – to deflect any anxiety, gauging the need for emotional support and encouragement. Many of the portraits are playful, irreverent even; the subjects appear to make fun of the constraints of ageing female subjectivity, relishing the chance to confound expectation and enjoying the thrill and simple freedom of nudity in a safe, semi-public space. There’s a whiff of the 19th century erotic postcard, but served up with the lashings of humour Linda Nochlin added to the gender inversions of the form.13 Those who cover their faces do not exude shame but rather an opportunity to act up, Hawkes’ sophisticated aesthetics incorporating their gestures into elements of formal beauty. 500 Strong emerges from the interrelation between artist and sitter and the solidarity between the participants themselves; it is a complex collaboration which invites neither passive contemplation nor voyeuristic consumption. Rather, through process and relationship, the project literally embodies the collective therapeutic effects of publicly owning once disempowering secrets, serving to change how we interact with ageing female bodies, including our own.

Hotham Street Ladies (Cassandra Chilton, Molly O’Shaunessy, Sarah Parkes and Caroline Price), Unbridled Abundance: Pink Bits ‘n’ Saggy Tits, 2020-2021, royal icing, food colouring, aluminium, mesh, canvas, MDF © Courtesy Hotham Street Ladies

Hotham Street Ladies (Cassandra Chilton, Molly O’Shaunessy, Sarah Parkes and Caroline Price), Unbridled Abundance: Pink Bits ‘n’ Saggy Tits, 2020-2021, royal icing, food colouring, aluminium, mesh, canvas, MDF © Courtesy Hotham Street Ladies

Flesh after Fifty – together with its planned public programmes and performances – has enhanced impact because it is contextualised by interdisciplinary research and investment in the wellbeing of older women. As such, its audiences have several points of entry to immerse themselves in the potentially transformative experience of art, to connect to a broader desire for cultural shift, to attune to a kind of solidarity that faces down the fear, transforms the shame, owns the excess and asserts the desire. And no work does this better than Unbridled Abundance: Pink Bits n Saggy Tits (2020–2021, royal icing, food colouring, aluminium, mesh, canvas, MDF) by the Hotham Street Ladies (Cassandra Chilton, Molly O’Shaunessy, Sarah Parkes and Caroline Price). “A sugary topography of wrinkles, folds, cracks and creases”,14 this installation droops and oozes and takes over the full space with monumentally sized breasts hanging from the rafters accompanied by an equally large bristly grey bush sprouting from spread legs on the floor.15 Here there is no pressure to embrace ageing by growing old like J Lo or Madonna, there is no norm to estrange us from our lived experience, there is no shame and no erasure. Here we can be openly sweet and salty, loose and louche, alive, in the world and ever full of desire.

Michelle Meagher, “Feminist Ageing: Representations of Age in Feminist Art”, in A Companion to Feminist Art, eds. Hilary Robinson and Maria Elena Buszek (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 181. Meagher also foregrounds how feminism in general has been regarded as focused on issues of youth, such as reproductive rights, labour, intimacy: 181.

2

This recent anthology is a promising sign of renewed art historical interest: Frima Fox Hofrichter and Midori Yoshimoto, eds., Women, Aging, and Art: A Crosscultural Anthology (New York: Bloomsbury, 2021). With essays on contemporary work by Joan Semmel and Miwa Yanagi, it takes a wide cultural and historical perspective to consider “a broad range of images of old women, ranging from medieval ‘old wives’ to contemporary re-imaginations of shamans and witches and empowering self-portraits” (editor’s description).

3

Sigmund Freud (1913), “The Disposition to Obsessional Neurosis: A Contribution to the Problem of the Option of Neurosis”, cited in Vivian Sobchak, “On Morphological Imagination”, in re:skin, Mary Flanagan and Austin Booth, eds. (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009), 106.

4

Vivian C. Sobchack, “The Leech Woman’s Revenge, or A Case for Equal Misrepresentation”, Journal of Popular Film, vol. 4, issue 3 (1975), 236-257.

5

Sandra Lee Bartky, “Foucault, femininity and the modernisation of patriarchal power”, in Writing on the Body: Female embodiment and feminist theory, Katie Conboy, Nadia Medina, Sarah Stanbury, eds. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 141.

6

Griselda Pollock, cited in Meagher, “Feminist Ageing: Representations of Age in Feminist Art”, 184.

7

For example, The Art of Ageing (2020-) by Canadian photographer Arianne Clément.

8

The concept of transageing was developed by Helene Moglen in her article “Ageing and Transageing: Transgenerational Hauntings of the Self”, Studies in Gender and Sexuality, Vol. 9, 2008, Issue 4, 297-311.

9

Meagher, “Feminist Ageing: Representations of Age in Feminist Art”, 182, citing Ana Cristofovici.

10

As Griselda Pollock imagines, cited in “Feminist Ageing: Representations of Age in Feminist Art”, 184.

11

The exhibition, originally planned for 2020, was eventually shown at Abbotsford Convent in Melbourne in 2021, and included the work of, amongst others, Janina Green, Penny Byrne, Ponch Hawkes, Maree Clarke, Hotham Street Ladies, Ruth Maddison, Deborah Kelly and Megan Evans: https://www.fleshafterfifty.com.

12

Online call for participants: https://fleshafterfifty.com/strong.html.

13

Linda Nochlin’s Buy my Bananas (1972) was a staged photograph featuring a naked man holding a tray of bananas beneath his genitals, satirizing an actual 19th century erotic postcard of a naked woman offering up a tray of apples under her breasts with the caption, Buy My Apples.

14

“Hotham Street Ladies” in Flesh after Fifty: Changing Images of Older Women in Art, exh.cat., Abbotsford Convent, Melbourne (7 March–11 April 2021), Melbourne, Abbotsford Convent, 2021, 22.

15

According to the artists, this work echoes the enormous 1966 sculpture, Hon – en katedral [She – a cathedral] – a collaboration between Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvedt: Hotham Street Ladies website: https://www.hothamstreetladies.com/unbridled-abundance.

Dr Jacqueline Millner is Professor of Visual Arts at La Trobe University. Her books include Conceptual Beauty: Perspectives on Australian Contemporary Art (Artspace, 2010), Australian Artists in the Contemporary Museum (Ashgate, with Jennifer Barrett, 2014), Fashionable Art (Bloomsbury, with Adam Geczy, 2015), Feminist Perspectives on Art: Contemporary Outtakes (Routledge, co-edited with Catriona Moore, 2018), Contemporary Art and Feminism (Routledge, 2021 with Catriona Moore) and Care Ethics and Art (Routledge, 2022, co-edited with Gretchen Coombs). She has curated major exhibitions and received prestigious research grants from the Australian Research Council, Australia Council and Create NSW.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Jacqueline Millner, "Unbridled Abundance: Contemporary Feminist Art and Ageing." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/une-abondance-debridee-lart-feministe-contemporain-et-le-vieillissement/. Accessed 12 July 2025