Ceija Stojka

Ceija Stojka, Auschwitz ist mein Mantel : Bilder und Texte, Vienna, Exil, 2008, translated in french as Auschwitz est mon manteau, et autres chants tsiganes, Paris, Bruno Doucey, 2018

→Sojka Ceija, Ceija Stojka, Lyon, Fage, 2017

→Meier-Rogan Patricia, Helmreich Franzi, Ceija Stojka : Bilder & Texte 1989-1995, Vienna, Patricia Meier-Rogan, 1995

Ceija Stojka: Esto ha pasado [This has Happened: Ceija Stojka], Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, November 22, 2019 – March 23, 2020

→Ceija Stojka, une artiste Rom dans le siècle, la Maison rouge-Fondation Antoine de Galbert, Paris, February, 23 – May 20, 2018

→Ceija Stojka, 1933 – 2013 : sogar der Tod hat Angst vor Auschwitz [Ceija Stojka, 1933 – 2013 : Even Death Fears of Auschwitz], Kunstverein Tiergarten – Galerie Nord, Berlin, June 21 – July 26, 2014 ; Gallery of Villa Schwartzsche, cultural office Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Berlin, July 2 – August 31, 2014 ; Ravensbrück memorial, Fürstenberg-Havel, July 13 – September 12, 2014

Austrian painter and poetess.

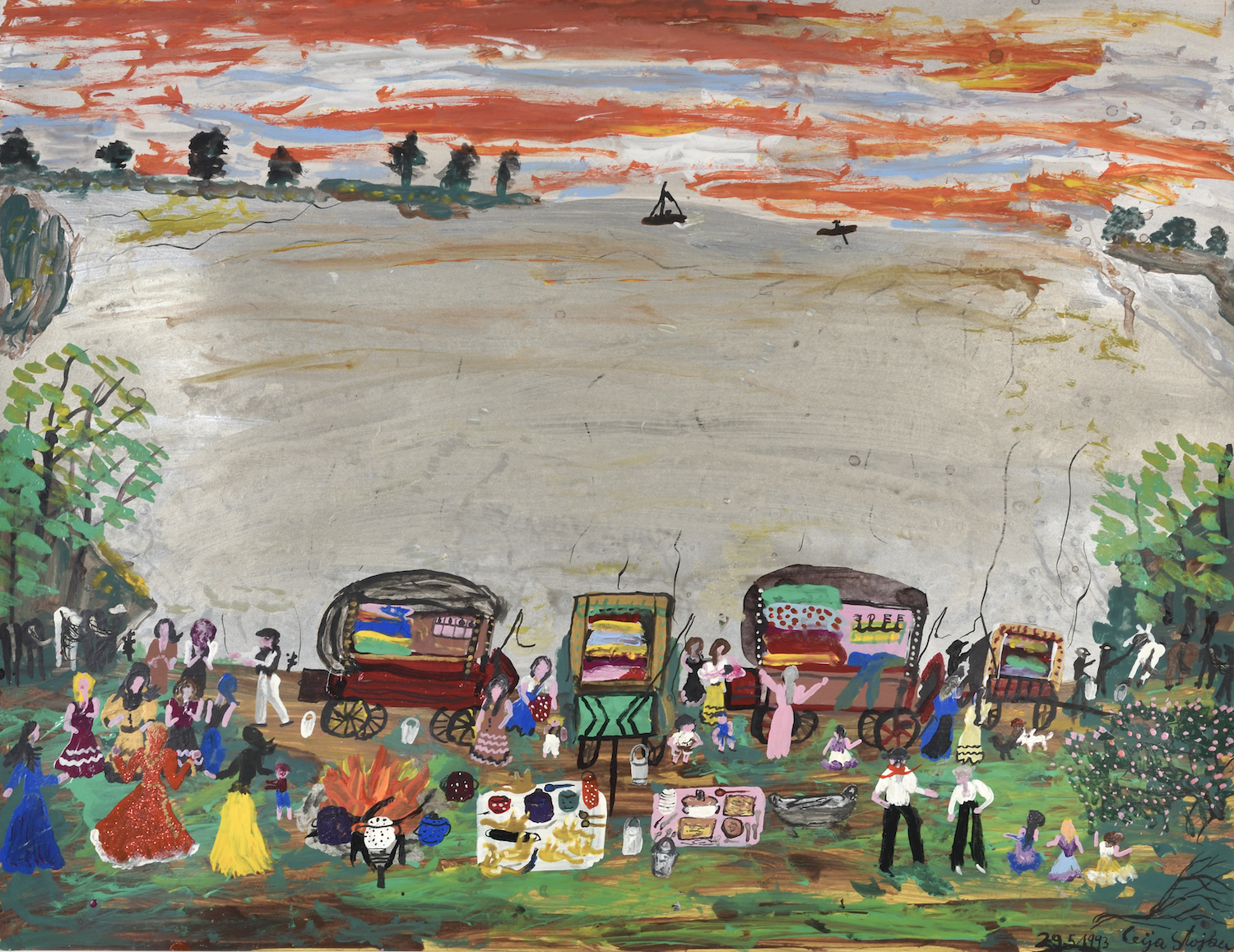

Ceija Stojka was born in the Austrian state of Styria. Her parents descended from a line of Romani horse traders, the Lovara, who were originally from Hungary but had settled in Austria two centuries earlier. While still only a child, due to the restrictions and discriminations levelled at the Tzigani community, her family was forced into a sedentary existence. In 1941 her father was deported to Dachau and her mother went into hiding with the children. The following year her father was transferred to the Hartheim Euthanasia Centre, where he was assassinated. In 1943 C. Stojka, her mother, and her five brothers and sisters were arrested and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. A year later she was sent to Ravensbrück with her mother and one of her sisters, where she witnessed scenes of appalling cruelty. The family found itself separated once again the following year and C. Stojka was moved to Bergen-Belsen before being liberated by British troops. She was later to claim that she had only survived her last camp by scraping the bark of a branch to release its sap.

C. Stojka returned to Vienna on foot with her mother, where they were reunited with her two sisters and two of her brothers who had managed to survive the camps. It is estimated that following the mass deportations of the late 1930s, 90 per cent of the Austrian Romani population were murdered. For those who survived and managed to return to Austria, harsh living conditions awaited them.

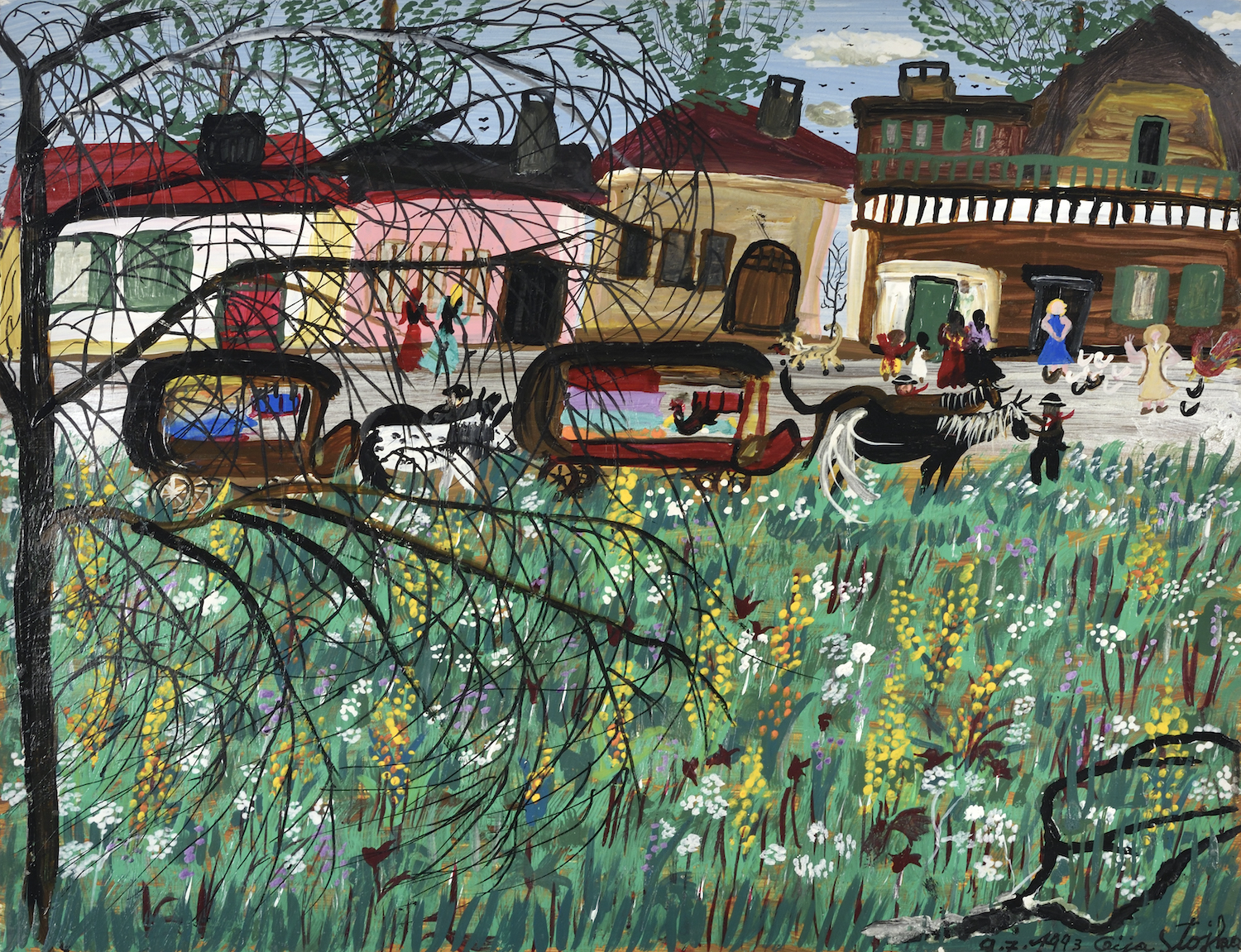

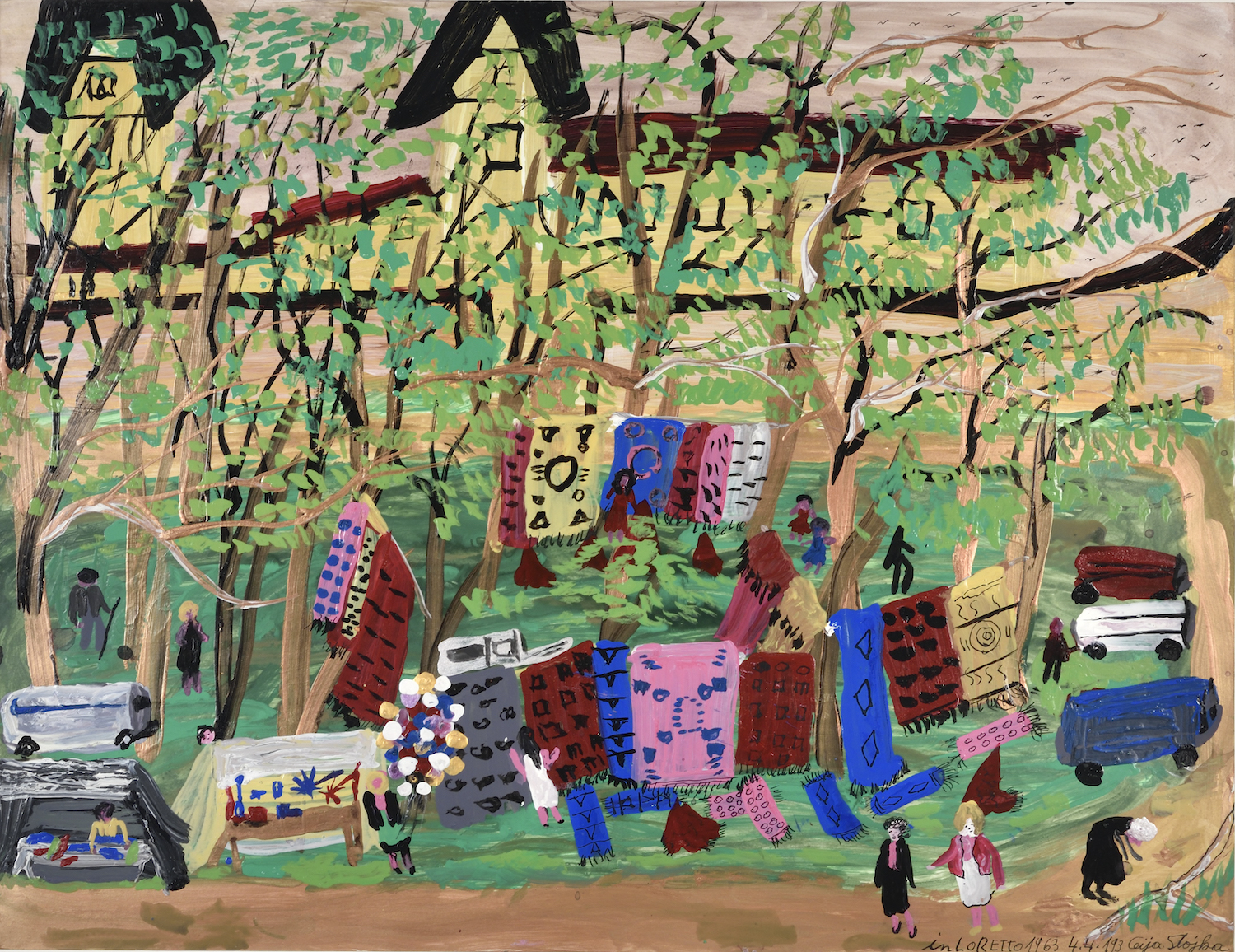

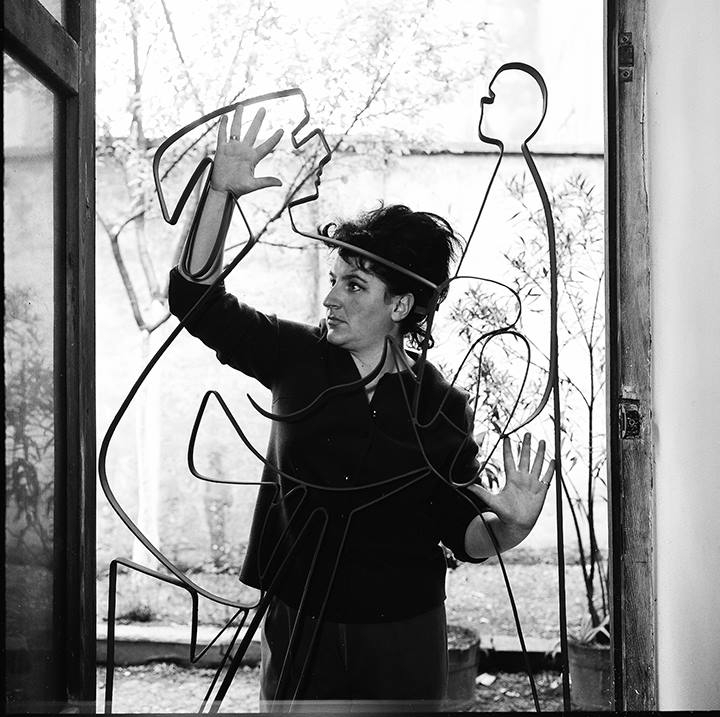

The Stojka family resumed its horse-trading business in the late 1940s; in 1955, C. Stojka, who was still living in Vienna, was selling fabrics door-to-door but a few years later she obtained a licence to sell carpets in markets. In the mid-1980s her brother Karl (1931-2003) began producing paintings depicting his experience in the concentration camps. In 1988 C. Stojka published her first text Wir leben im Verborgenen (We live in hiding), recalling her memories of the war, and also produced her first paintings and drawings.

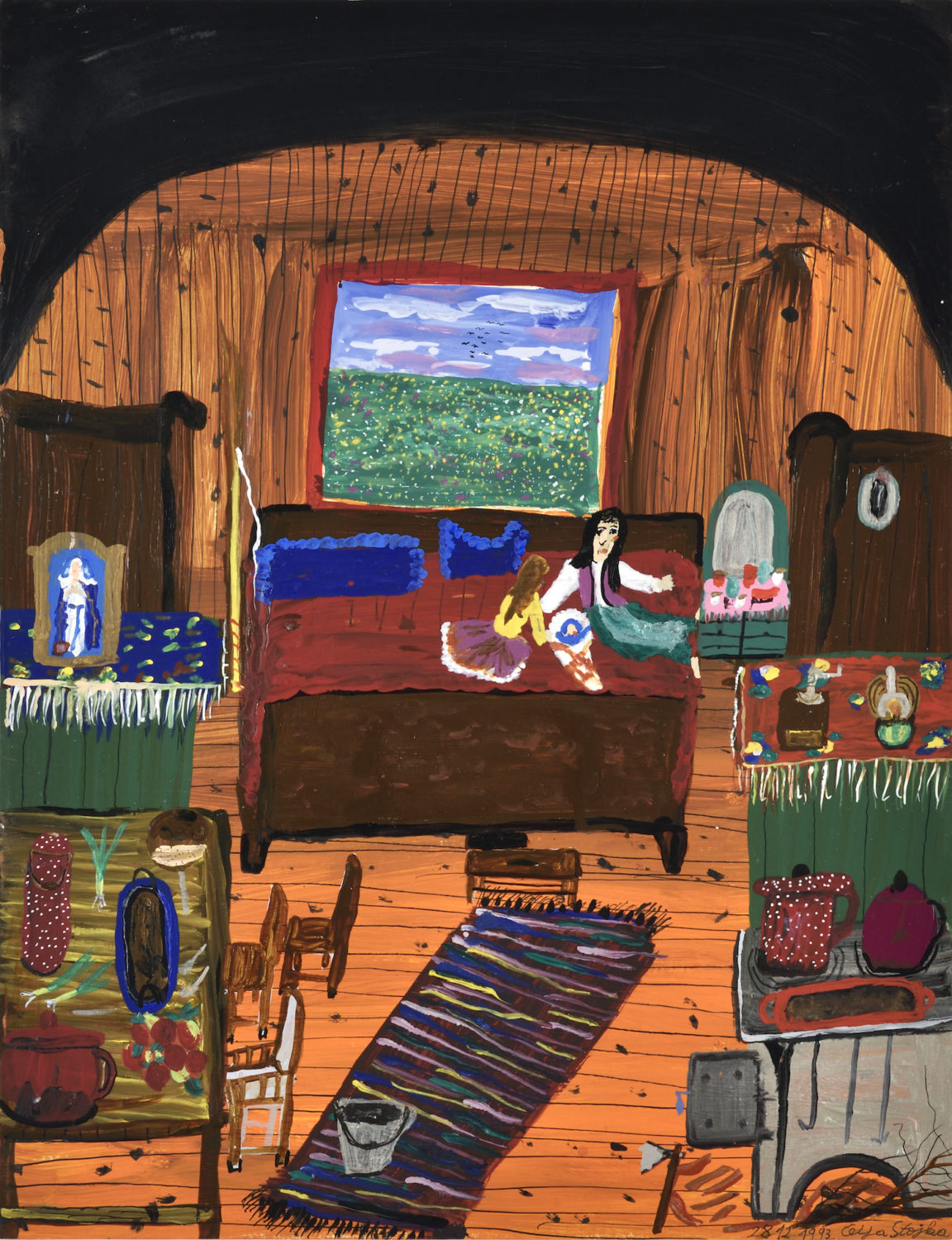

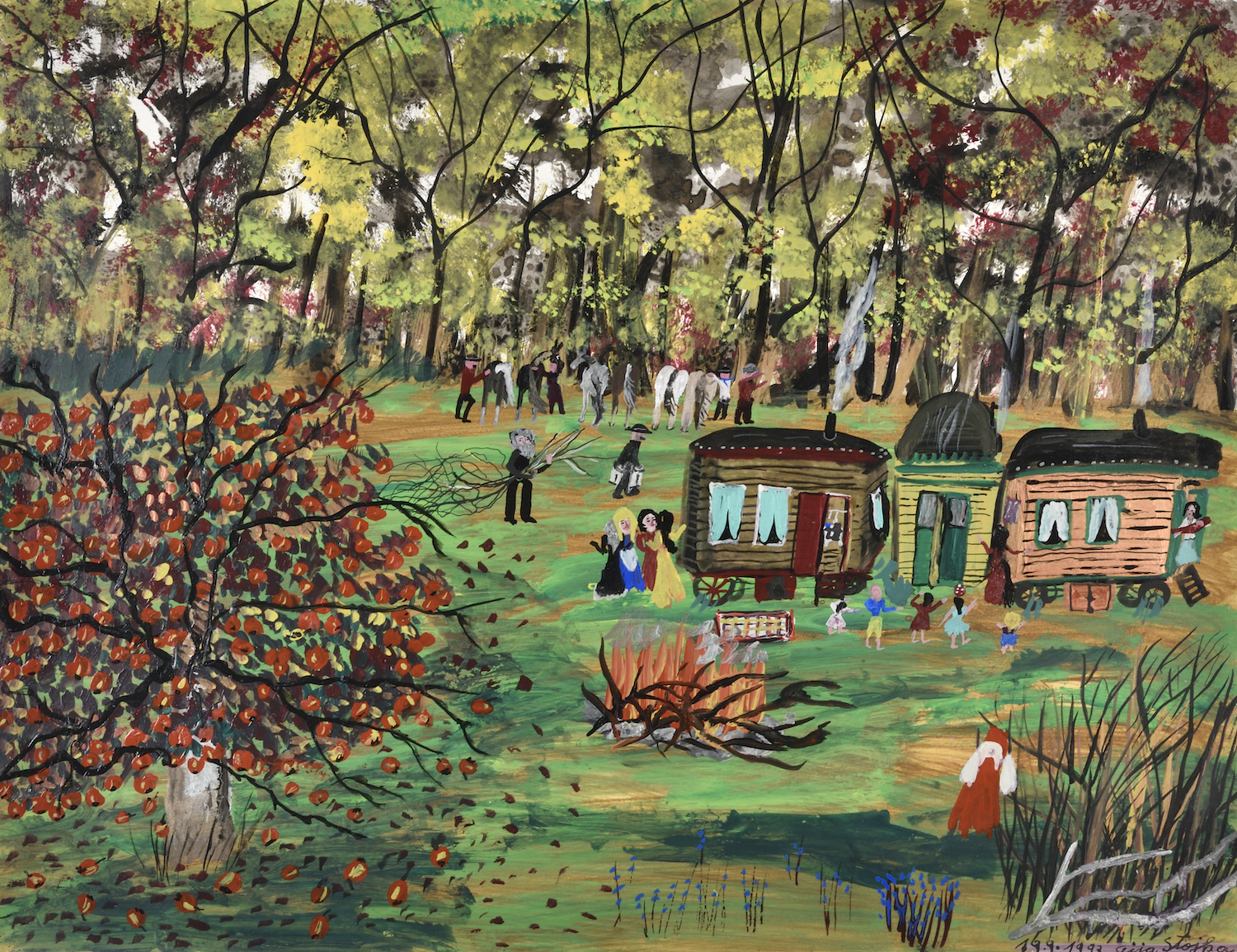

It is not easy to categorise her pictorial output according to period, as she tended to favour an interweaving of different autobiographical elements rather than work in series: vibrantly coloured works reflecting a happy childhood surrounded by her family are juxtaposed with other infinitely darker works, depicting the months in hiding, the shock of the arrest, the episodes of violence and brutality she experienced in the camps, and her liberation.

In her drawings and paintings, C. Stojka worked with both hand and brush, in sweeping forceful movements, on cardboard, paper or paperboard, using acrylic or oil paint, coloured sand, biro, ink or sequins. The scenes featuring the concentration camps are usually complemented by texts evoking her mother’s or her own voice, or the orders of her Nazi persecutors. In memory of Bergen-Belsen, her signatures on some of the works are flanked by a drawing of a branch, as in No one had ever seen that… (1995) and There Was No Room for the Living There (2005).

Her work was shown in public for the first time in 1991, at the Amerlinghaus in Vienna, and subsequently in a great many more institutions, including the Ravensbrück Memorial Site (1996-1997) and the Jewish Museum Vienna (2004). In 2013 she published a collection of poetic essays; she died that same year. Today her oeuvre continues to be shown in both solo and group exhibitions.

Exhibition visit, Ceija Stojka at la Maison rouge | Beaux-Arts magazine

Exhibition visit, Ceija Stojka at la Maison rouge | Beaux-Arts magazine  Robert Desnos et Ceija Strokja, art stronger than babarism | Conference, Université de Nantes (french)

Robert Desnos et Ceija Strokja, art stronger than babarism | Conference, Université de Nantes (french)