Emiria Sunassa (Emiria Soenassa)

Dirgantoro, Wulan, ‘Islands, archipelago and the postcolonial subconscious’, ISSUE Art Journal, ed. 4: Islands, LaSalle College of the Arts, Singapore, 2015, p. 45–52. Also accessible here.

→Arbuckle, Heidi, ‘Performing Emiria Sunassa: Reframing the Female Subject in Post/Colonial Indonesia’, PhD. dissertation, The University of Melbourne, 2011.

Solo exhibition, Indische Institute, Amsterdam, 1950

→Solo exhibition, PUTERA by Keimin Bunka Shidōsho [Pusat Tenaga Rakyat – Center of People’s Power], Jakarta, 1943

→Persatuan Ahli Gambar Indonesia or Persagi [Association of Indonesian Draftsmen], Batavische Kunstkring [Dutch Association of Art Circles in Batavia], Jakarta, 1941

Painter.

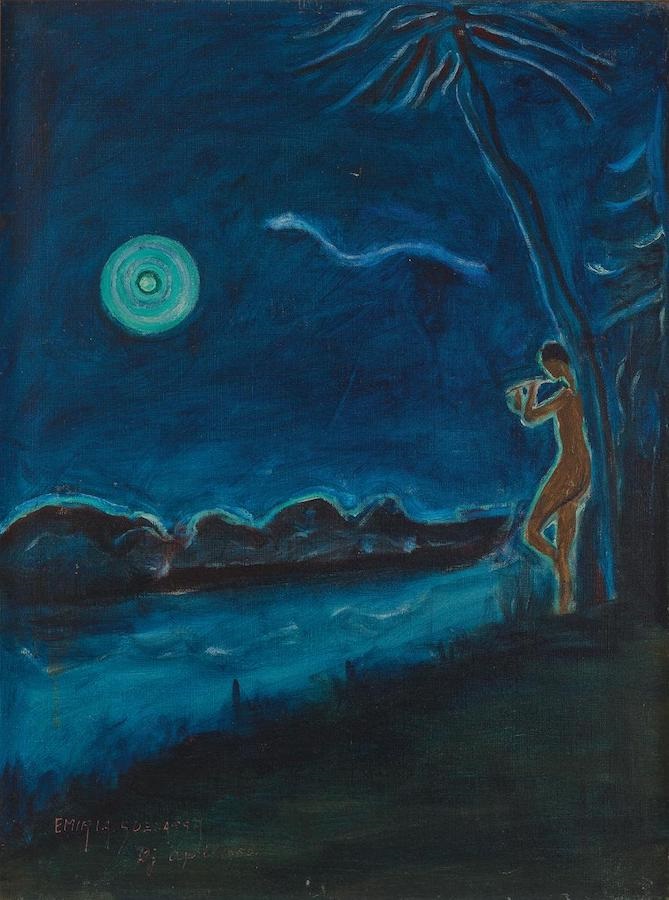

Figures in the paintings of Emiria Sunassa are people from a variety of ethnicities living in different parts of an archipelago that was then very recently claimed as Indonesia. E. Sunassa painted portraits of these people in their everyday lives, either simply being themselves in a certain moment in their daily activities (e.g. Pasar [Market, 1943]; A woman picking fruit, ca. 1940s; or Rosin harvest, date unknown) or performing their best on some special occasion (Bride of Central Sulawesi, 1950; Kembang kamboja [Frangipani flower, 1958]; Unknown title, 1955). A mixture of the two approaches is not uncommon in her canvases. For example, Nogati menunggu siapa? [For whom is Nogati waiting?, ca. 1941–1946}, in which the model is captured from behind, in her complete Balinese dancer costume and hairstyle. Depicted with a distorted right shoulder, waist and left hand, Nogati sits uneasily next to a pool of lotus. Or, Irian Man with bird of paradise (1948), who is captured full frontal, like portraits in legal documents, with a formal straightforward gaze, yet conveniently hugging a cendrawasih, an endemic Papuan bird.

During the Japanese occupation, the Gunseikanbu [a branch of the occupying army] published a book of biographies entitled Orang Indonesia Jang Terkemoeka di Djawa [Important People of Indonesia in Java, 1944] in which E. Sunassa’s biographical entry concluded with, “Up to the date of compilation of this directory (in 1943), she has been a painter”. This is one of the very few self-claims to be found – the book is known to have gone through an approval process by each person included. She taught herself stenography and typing (until 1914); took nurse training at the Cikini School (until 1919); was employed as secretary to A. H. Giel, the director of Bank v. Indie in Jakarta (until 1924); was the administrator and director for the agricultural enterprise NV Veregnig de Klatensfche Cultuur Mij in Oba, Halmahera (until 1928); learnt about commerce (until 1929); was the administrator for the Artama Tea Company (until 1937); investigated gold and mineral mining (until 1939); and learned about Islam whilst doing secretarial work for Prof. Dr. G. F. Pijper (until 1941). E. Sunassa’s vast interest in learning seems to have made it possible for her to travel and do distinct things in her life, thus meeting a range of different people at different stages of their lives.

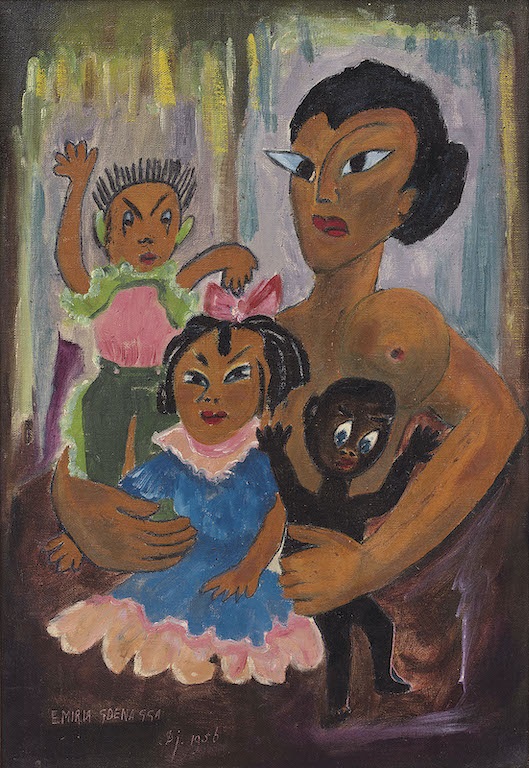

Performing Emiria Sunassa (2011), an influential scholarly work by Heidi Arbuckle, describes a native exhibition at the Kolff bookstore in 1940 as E. Sunassa’s debut. This was followed by the ground-breaking exhibition by the Persatuan Ahli Gambar Indonesia or Persagi [Association of Indonesian Draftsmen] at the Batavische Kunstkring [Dutch Association of Art Circles in Batavia], in 1941. In that decade, she participated in at least eleven group exhibitions and conducted three solo exhibitions: two in Jakarta and one at the Indische Institute in Amsterdam in 1950. Unlike many artists of her time, who opposed the Western exotic view of the archipelago, a genre labelled by the natives as mooi Indiesche [beautiful Indies], throughout her career, E. Sunassa painted fellow Indonesians from a vast variety of ethnicities with a familiar gaze. Her camaraderie with minority ethnic groups is consistent throughout her oeuvre. An excellent example of this is Keluarga [Family, 1956] in which each member of the family is – very casually – of different skin colour, emphasised with varying facial features that highlight the differences in their genealogy. Depicting three children and a mother, Keluarga (1956) can also be read as E. Sunassa’s cosmopolitanism – a stance that gave her a foundation to value particular human lives, beliefs and therefore significance.

A biography produced as part of the programme The Flow of History. Southeast Asian Women Artists, in collaboration with Asia Art Archive

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023