Georgia O’Keeffe

Castro Jan Garden, The Art & Life of Georgia O’Keeffe, New York, Crown, 1985

→Lynes Barbara Buhler, Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven/Washington, Yale University Press/National Gallery of Art, 1999

→Kristeva Julia, Cowart Jack & Laroche Martine, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paris, A. Biro, 1989

Georgia O’Keeffe, National Museum of Modern Art, Centre Pompidou, Paris, September 8–December 6, 2021

→Georgia O’Keeffe et ses amis photographes, Musée de Grenoble, 7 November 2015–7 February 2016

→Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.; Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, September 2009–September 2010

→Georgia O’Keeffe, Kunstforum, Vienna, 7 December 2016–26 March 2017

American painter.

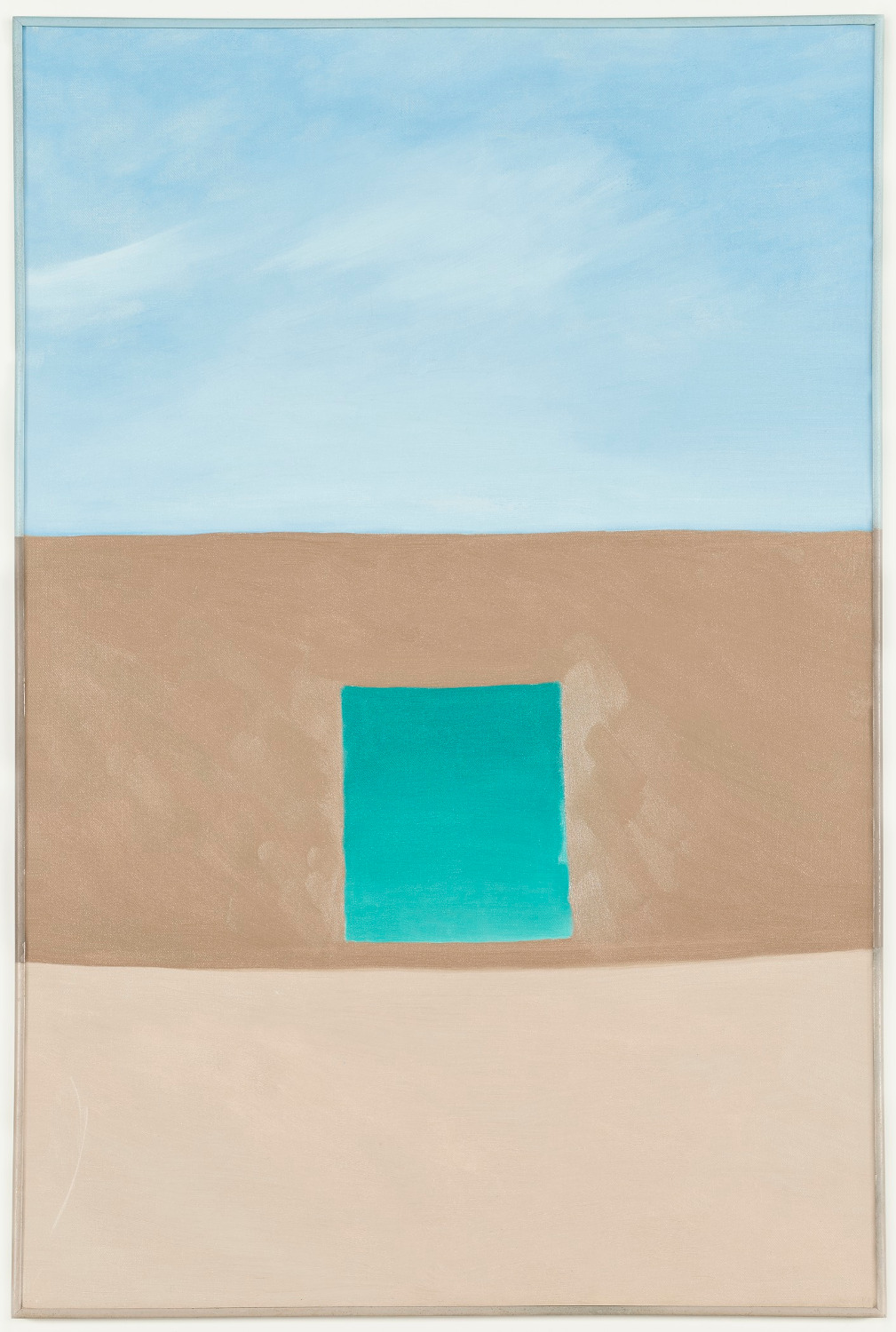

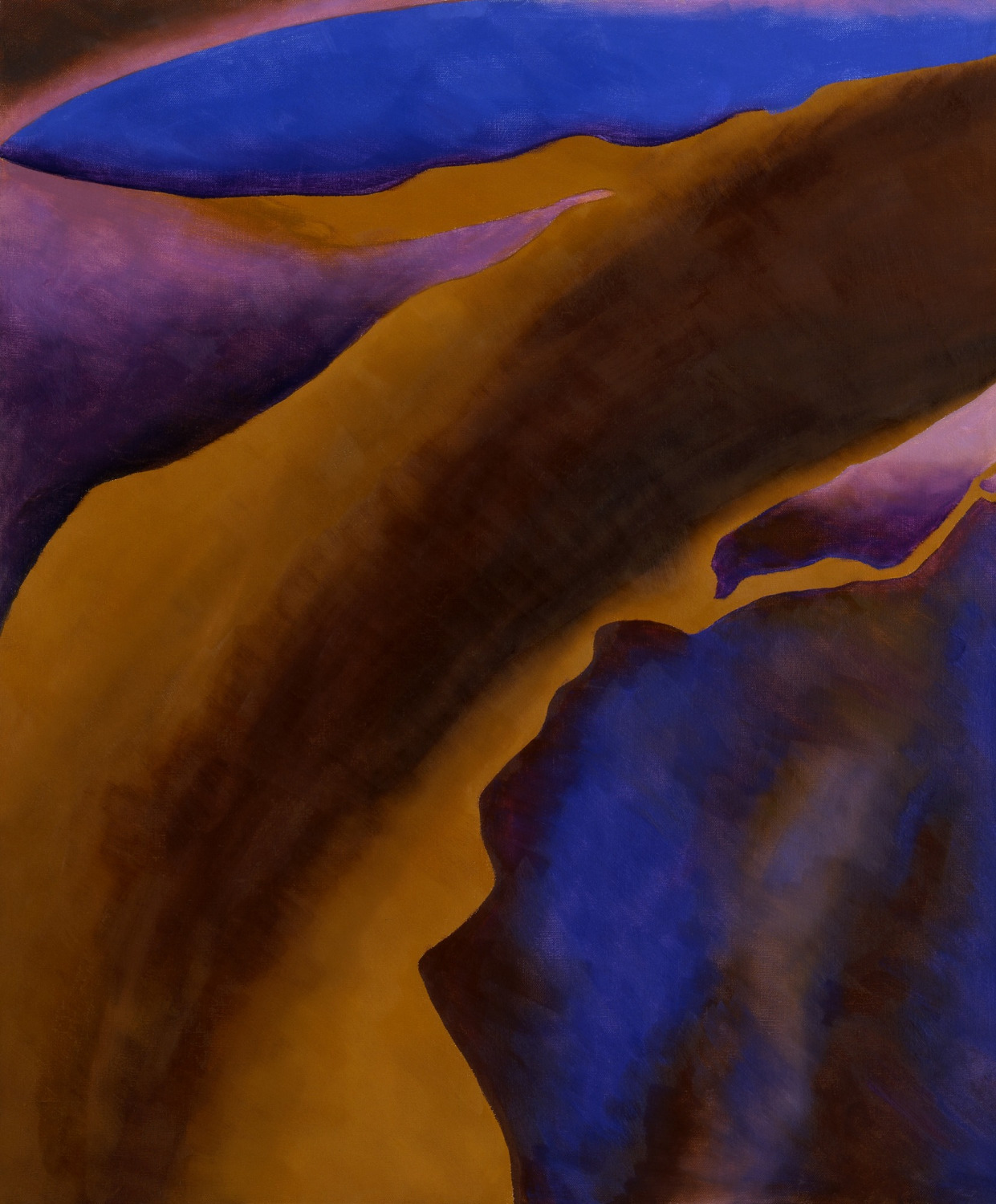

Georgia O’Keeffe was the only woman painter of the first wave of American “abstractionism” formed around Alfred Stieglitz in New York. She left her family’s farm in 1907 to study at the Art Institute in Chicago, then at the Art Students League in New York – an academic training which enabled her to earn a living teaching fine arts and commercial art as from 1911. Influenced by the French avant-garde and the writings of Kandinsky, G. O’Keeffe adopted an “organic” abstract approach similar to Arthur Dove’s, considered a pioneer of American abstract painting. Geometrical shapes, graceful and wavering curved lines, and glowing spaces lit up by flashes of colour allowed her to create series of paintings in which she could represent the multiple modulations of her introspection and define a singular style, distancing herself from other early American “abstracts” like Marsden Hartley and John Marin. Perhaps the most decisive photographer and gallerist in New York at the time, A. Stieglitz (editor of the review Camera Work) held a solo exhibition of her work in 1917, saluting her new incandescent watercolours in which light played as important a part as abstract composition. In 1918 the painter joined him in New York, where he devoted an exhibition to her every year. The pair would eventually marry in 1924. The questioning of natural cosmic forces became the central theme of her work as from 1919.

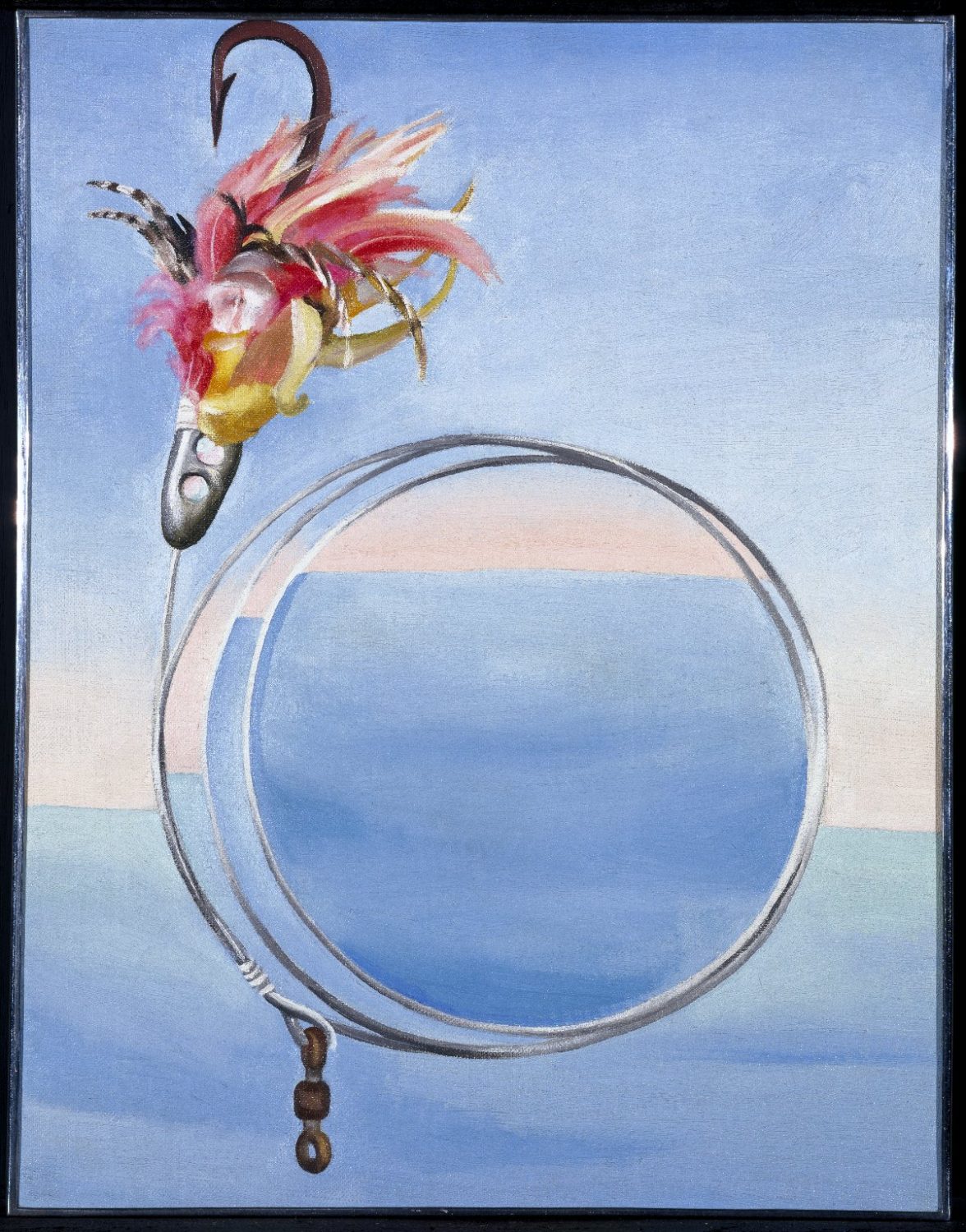

Her non-mimetic, almost abstract paintings (Lake George with Crows, 1921) were “inner landscapes”, mental projections of sorts, defined by chromatic variations: the artist readily explored a single colour – midnight or ocean blue (Blue, 1916-1917), or solar red –, which she used in various series of combinations and shades, very fluid but always precisely defined. These “subjective” formal modulations express powerful feelings of rapture: flora, sea and the cosmos mingle in a same expanding flow, which imposes its growth pattern in parallel or concentric curves and uniform symmetries. In addition to these compositions, O’Keeffe continued to paint precise figurations of objects (fruit, flowers, shells) or nudes, and even cityscapes (City Night, 1926), exploring their explosive and secret “nature”, which fascinated her as much as that of sunsets, clouds, and waves (Grey Line with Lavender and Yellow, 1923-1924). As such, referent subjects almost disappear in many of her giant flower paintings from the 1920-1930s: the abstract orbs of Grey Blue and Black-Pink Circle (1929) may evoke both the headpiece of a Native American doll and the petals of a flower. Because they were the visual expression of a woman, American critics were prompt to underline the analogy between these figurative abstractions and the curling shapes of an intimate, eminently sexual realm.

While the wave of American Abstraction underwent criticism, or at least discredit, in the 1930s – culminating in 1935 on the occasion of the exhibition Abstract Painting in America at the Whitney Museum in New York –, Georgia O’Keeffe’s work found a new audience in the followers of the new non-geometric biomorphic abstraction movement, encouraged by Alfred Barr at his exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in 1937. And while the upholders of cold geometrical abstraction criticised her for her mystical “formalism” poised between abstraction and figuration, and for her fondness for fauve expressionist colour – formalism which met the new injunctions for a subjective expression of a “vital drive” –, these qualities would draw the attention of both Abstract Expressionists as from 1945-55 (Gottlieb, De Kooning) and the disciples of Optical Abstraction, who admired the boldness of her compositions. Her resolutely independent approach and pioneering work paved the way, fifty years earlier, for a form of “anti-purist, anti-Bauhaus, anti-systemic (…), additive, subjective, local, specific, colourful, joyful, whimsical” abstraction advocated by the feminist artist Joyce Kozloff in 1976. The Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation opened in Abiquiú (New Mexico) in 1998.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Georgia O’Keeffe : An Artist in the Far West | Arte

Georgia O’Keeffe : An Artist in the Far West | Arte  Georgia O'Keeffe celebrated in London

Georgia O'Keeffe celebrated in London