Research

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, State Names, 2000, oil, collage and mixed media on canvas, 121.9 x 182.9 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum © Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

In a discussion in 2023 at SITE Santa Fe, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1940–) asserted, “Our bodies are this land, this land is our bodies.”1 The prominent Salish and Kootenai artist’s statement served as a reminder to the audience that Indigenous peoples have a deep-rooted connection to their homelands that shape their cosmologies, religions, cultures and the very act of survival. The integration of body and land reflects a kincentric understanding of the world that acknowledges a reciprocal connection or kinship between human and other-than-human life forms. Kincentricity refers to a prominent Indigenous worldview that considers humans and the natural world at large as part of an extended familial relationship.2 People, animals, plants, the sky and the land itself all exist in an intimately intertwined relationship.3 This unique understanding of land as an ecosystem of living beings rather than a commodity differs considerably from that of settler populations in North America and is frequently reflected in contemporary Native art, scholarship, lifeways and activism. While the genre of landscape has played a dominant role in the history of North American art, Indigenous artists’ contributions to these artistic discussions within the institutions that function as the art world have only been seen in the last sixty years. This article provides a brief overview of how three influential Native American women artists, J. Smith, Kay WalkingStick (1935–), and Emmi Whitehorse (1957–), have challenged the conventions of the genre and used their works to both express Indigenous worldviews and acknowledge Native land sovereignty and histories.

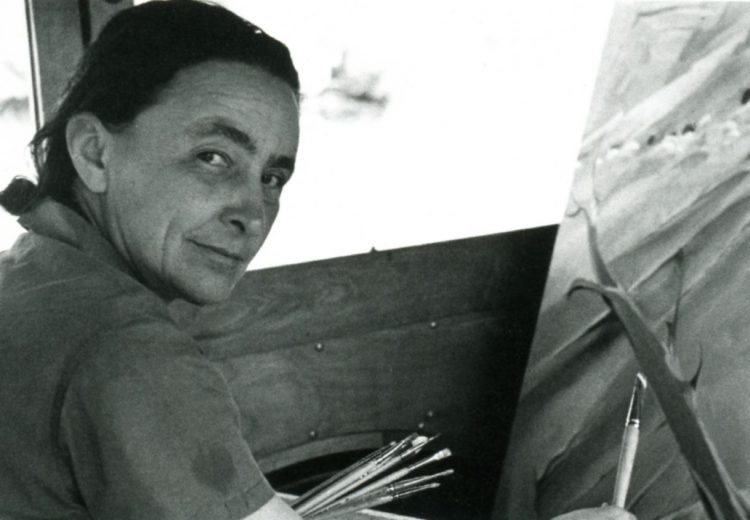

For some brief historical context, the landscape genre in the United States reached peak prominence in the nineteenth century with Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole (1801–1848), Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) and Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900). While these artists celebrated the beauty of the ‘New World’, they simultaneously perpetuated the fantasy that these lands were unpopulated and ripe for European settlement and lamented the loss of these landscapes to unchecked development. By the early twentieth century, with American expansion westward complete, landscape art became a romantic escape from urban and suburban realities. Modernists like Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) crafted abstract and sensual paintings of the American southwest, and photographers like Ansel Adams (1902–1984) advocated for environmental conservation. Though this history is long and complex, it was rooted in and at times critiqued a Euro-Christian worldview that foregrounded human domination over the land and its ecosystems. Indigenous peoples were excluded from these artistic discussions at an institutional level, and their creative work was frequently relegated to commercial or ethnographic production. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, artists like J. Smith, K. WalkingStick, E. Whitehorse and their male counterparts overcame institutional barriers and began sharing their work in galleries, museums and project spaces. It was in this moment and in the decades that followed that Native American artists challenged the Euro-American landscape pictorial genre.

Since the beginning of her career in the 1970s, J. Smith has played a crucial role in challenging the artistic conventions of the Euro-American landscape. Thematically, her works have expressed kincentric understandings of nature and have highlighted the contested political and cultural realities of the American continent. Instead of presenting representational depictions of a scenic view, her works are often abstract. Her landscapes from the first decades of her career, such as Cheyenne Series #5 (1984) or Tree of Life (1987), exclude horizon lines and depict a more holistic representation of nature.4 Additionally, she flattens spatial structure to break the window looking onto the world that is typical of the genre of landscape. Unlike the classical American landscape artists who came before her, she refrains from inviting viewers into pictorial spaces. Instead, her compositions act more as a barrier and emphasise depictions of life and movement.5 Unlike traditional American landscape paintings that are often devoid of or minimise the presence of Indigenous peoples, J. Smith’s works show viewers a space that is teeming with the presence of human, animal and plant life. These works not only challenge the conventions of the traditional landscape genre but clearly express a kincentric worldview.

Beginning in the early 2000s, J. Smith pivoted from her abstract landscapes and developed her well-known series of map paintings. Works like State Names (2000), Memory Map (2000) and Unhinged (Map) (2018), flip map orientations and challenge place names and formal borders. These works grapple with the fact that the western hemisphere is a contested space, filled with hundreds of Indigenous nations with their own political, historical and cultural ties to lands that settlers now reside on and claim as their own. In these modified maps, J. Smith emphasises Native knowledge and connection to the land by incorporating Indigenous languages, petroglyphs and designs. Ultimately, the works reflect on maps as manifestations of colonial control, divisions and naming. For example, in State Names, J. Smith only inscribes American, Canadian and Mexican state names that have Indigenous linguistic roots.6 The painting highlights the fact that Indigenous groups existed on these lands long before the creation of modern nation states and borders, and continue to have their own histories and geographies.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, State Names, 2000, oil, collage and mixed media on canvas, 121.9 x 182.9 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum © Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Cheyenne Series #5, 1984, collage of paper and fabric with watercolor, pastel, and graphite pencil, 30 x 22 in / 76.2 x 55.9 cm, Tia Collection © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Memory Map, 2000, oil, acrylic, and paper on canvas, 36 x 48 in / 91.44 x 121.92 cm, Seattle Art Museum © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

K. WalkingStick, of Cherokee and European descent, has also been a leading innovator in the American landscape genre. Throughout her career, she has crafted both abstract and representational landscapes that emphasise feeling and memory, and assert Indigenous’ connections to the lands of North America. Like J. Smith, K. WalkingStick’s early landscapes were abstract but differed in that they were not focused on life and movement. Instead, works like Montauk I (1983) and Satyr’s Garden (1982) are compositionally stark and are what the artist considers “a description of a landscape”.7 The pieces utilise wax, ink and natural materials and suggest a visceral feeling or even a memory of a landscape. In the decades that followed, K. WalkingStick adopted a diptych format, which presented both abstract and representational renderings of land. A standout piece from this era is Blame the Mountains III (1998) which explicitly demonstrates a bodily connection to physical space. One side of the diptych features an outline of the artist’s own body and even mimics the arc of the mountain range situated beside it. The piece suggests that land and bodies are intimately intertwined and are made up of the same material.8

Kay WalkingStick, Blame the Mountains III, 1998, oil on wood, oil, brass leaf on canvas, 32 x 64 in / 81.28 x 162.56 cm, Allentown Art Museum, Allentown © Kay WalkingStick

Kay WalkingStick, Orilla Verde at the Rio Grande, 2012, oil on wood panel, 40 x 40 in / 101.6 x 101.6 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. © Kay WalkingStick

Beginning in the early 2000s, K. WalkingStick began crafting traditional American landscapes which feature overlays of abstract Native American designs. Like J. Smith’s maps, these works focus on North America as a contested space. Works such as Orilla Verde at the Rio Grande (2012) and Niagara (2022) remind viewers that all of North America is Indigenous land. K. WalkingStick’s paintings serve as corrective histories to the classical American landscapes of the likes of T. Cole and A. Bierstadt. Viewers of these pieces cannot enter the pristine beauty of the landscape without first acknowledging the traditional abstract Native design, which creates a visual barrier. The use of these designs on the paintings serves as a land acknowledgment, a reminder that Indigenous peoples continue to live and have historical, political, and spiritual connections to the whole of North America.

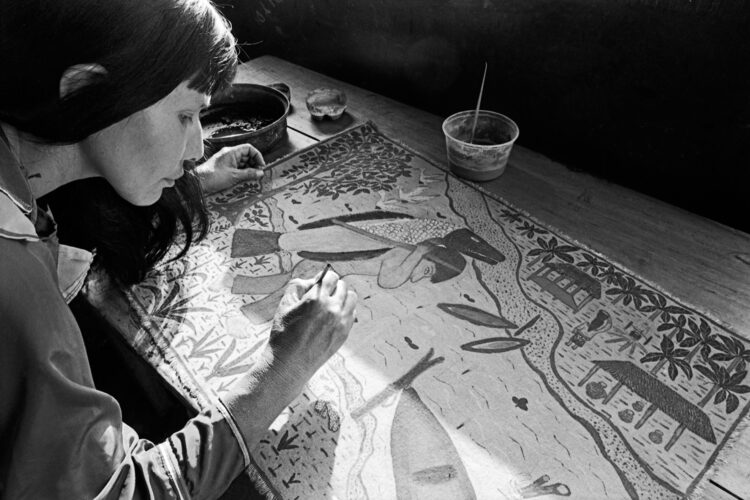

K. Whitehorse, of the generation following K. WalkingStick and J. Smith, has spent her career crafting mixed-media landscapes primarily set in her homelands of the Navajo Nation. Working within fields of colour, the artist makes visible the traces left behind by human, animal and plant life. Like many other Indigenous artists, she depicts a holistic understanding of land, one that excludes delineations between land and sky. Instead, her works revolve around “being completely, micro-cosmically within a place” and emphasise the harmonious possibilities of the natural world.9 Like J. Smith, her landscapes present a kincentric worldview but also honour the Navajo philosophy of hózhó, or the aspiration of creating harmony between humanity and the natural world. While most of her works have been apolitical, in 2015 she crafted the triptych Outset, Launching, Progression. This large scale, oil on canvas piece confronts the long history of resource extraction on Navajo lands. The work charts her homeland before human interference, the arrival of colonial capitalist industries and finally the disastrous aftereffects of resource extraction on the land itself.10 Like her artistic contemporaries, E. Whitehorse creates innovative landscape compositions that resist Euro-American conventions and voices her cultural-specific understanding of land and its intimate relationship to humans and history.

Emmi Whitehorse, Fire Weed, 1998, chalk, graphite, pastel and oil on paper mounted on canvas, 38 1/2 x 50 in / 97.8 x 127 cm, Brooklyn Museum, New York, gift of Hinrich Peiper and Dorothee Peiper-Riegraf in honor of Emmi Whitehorse © Emmi Whitehorse’s estate

As stated at the beginning of this article, there is a plethora of Indigenous artists that have challenged the European-American landscape. This article has focused on only a few of the most prominent Native American women artists of the twentieth century who are redefining the American landscape tradition, namely K. WalkingStick, J. Smith and E. Whitehorse. Together, they challenge dominant artistic traditions, bring attention to often ignored subjects and call into question popular perceptions of land. Since the end of the twentieth century, the topic of Indigenous landscape art has gained wider attention with prominent exhibitions such as Our Land/Ourselves (1991–1993), Off the Map (2007), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map (2023), Our Land Carries Our Ancestors (2023–2024), and Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School (2023–2024), amongst others.11 Such shows, two of which were curated by J. Smith, have also featured the works of younger generations of artists who are continuing to push the boundaries of landscape art. Artists like Wendy Red Star (1981) have crafted artificial idealised landscapes and portraits to critique the Hudson River landscape tradition and photographers like Edward Curtis, whose representations of Indigenous culture have long been seen as theatrical rather than documentary. Others, such as Athena LaTocha (1969–), are crafting large scale earthworks-inspired pieces that consider the long histories of interactions between humans and nature. Importantly, these artists have provided viewers of their work with new lenses to see the land we inhabit and to rethink our collective relationship with our fragile world.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Jeffrey Gibson, “Jaune Quick-to-See Smith in conversation with Jeffrey Gibson”, filmed 2023, SITE Santa Fe video, 46:56. Accessed 2 November 2024: https://youtu.be/cX3cQSIPI6A?si=ObMG–zmU1tIJbtb.

2

Dennis Martinez, “Redefining Sustainability through Kincentric Ecology: Reclaiming Indigenous Lands, Knowledge, and Ethics”, in Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Learning from Indigenous Practices for Environmental Sustainability, ed. Melissa K. Nelson and Dan Shilling (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 140.

3

Heather Ahtone, “Sky as Place, Land as Body, Landscape as Spiritual Compass”, in The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art By Native Americans, exh. cat. (Washington D.C. and Princeton, New Jersey: National Gallery of Art and Princeton University Press, 2023), 13–19.

4

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Land/Landbase/Landscape”, in The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art By Native Americans, exh. cat. (Washington D.C. and Princeton, New Jersey: National Gallery of Art and Princeton University Press, 2023), 24.

5

Liz Neely, “The Landscapes of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith”, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, 10 July 2020, https://www.okeeffemuseum.org/exploring-the-landscapes-of-jaune-quick-to-see-smith/.

6

Dr. Anne Showalter and Dr. Beth Harris, “What’s in a map? Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s State Names”, Smarthistory, 27 September 2019, accessed 14 April 2024, https://smarthistory.org/smith-state-names/.

7

Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto, Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School (New York: New York Historical Society, 2023), 26.

8

Kate Morris, Shifting Grounds: Landscape in Contemporary Native Art (Seattle: The University of Washington Press, 2019), 116–117.

9

“Emmi Whitehorse: Mapping the Microcosm”, Chiaroscuro Contemporary Art Gallery Santa Fe, accessed 30 March 2024, https://chiaroscurosantafe.com/2019/06/22/emmi-whitehorse-mapping-microcosm/.

10

Emmi Whitehorse, “Artist Emmi Whitehorse – Santa Fe, New Mexico”, filmed 2015, Chiaroscuro Santa Fe video. https://youtu.be/U_DxWv_GWMc?si=wzsuivEmWFqeV7cw.

11

Our Land/Ourselves: American Indian Contemporary Artists (Albany: University Art Gallery, University at Albany, 1 February–17 March 1991), Off the Map: Landscape in the Native Imagination (National Museum of the American Indian, New York, 3 March–3 September 2007), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map (New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 19 April–13 August 2023), The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 22 September 2023–15 January 2024), Kay WalkingStick / Hudson River School (New York City: New York Historical Society, 20 October 2023–14 April 2024.

Raven Manygoats is a Diné and Bilagáana History PhD candidate at Rutgers University. Her research focuses on Native American women’s activism in the era of Red Power. Her work examines both radical and grassroots efforts made by Native American women to ensure both land and bodily sovereignty in the late 20th century. In her work, she draws on Indigenous feminist theory, Native cosmologies, oral tradition and materials produced by organisations like the American Indian Movement (AIM). Additionally, she serves as a graduate assistant for the Art of the Americas at Rutgers’ Zimmerli Art Museum.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Raven Manygoats, "“Our Bodies Are This Land”: Indigenous Women Artists’ Depictions of the Natural World." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/nos-corps-ce-sont-ces-terres-les-representations-de-la-nature-par-les-artistes-femmes-autochtones-damerique/. Accessed 2 July 2025