Gisèle Freund

Gisèle Freund : Photographer, New York, Abrams, 1985

→Breun-Ruiter Marita, Gisèle Freund, Berlin-Frankfurt-Paris, Fotografien 1929-1962, Berlin, Jovis, 1996

→Freund Gisèle, Le monde et ma caméra, Paris, Denoël, 2006

Gisèle Freund, Itinéraires, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 12 December 1991 – 27 January 1992

→Gisèle Freund, l’œil frontière, Paris 1933-1940, Musée Yves Saint Laurent, paris, 14 October 2011 – 29 January 2012

→Gisèle Freund y su cámara, Museo de arte moderno, Mexico, 22 April – 2 August 2015

German naturalised-French Photographer.

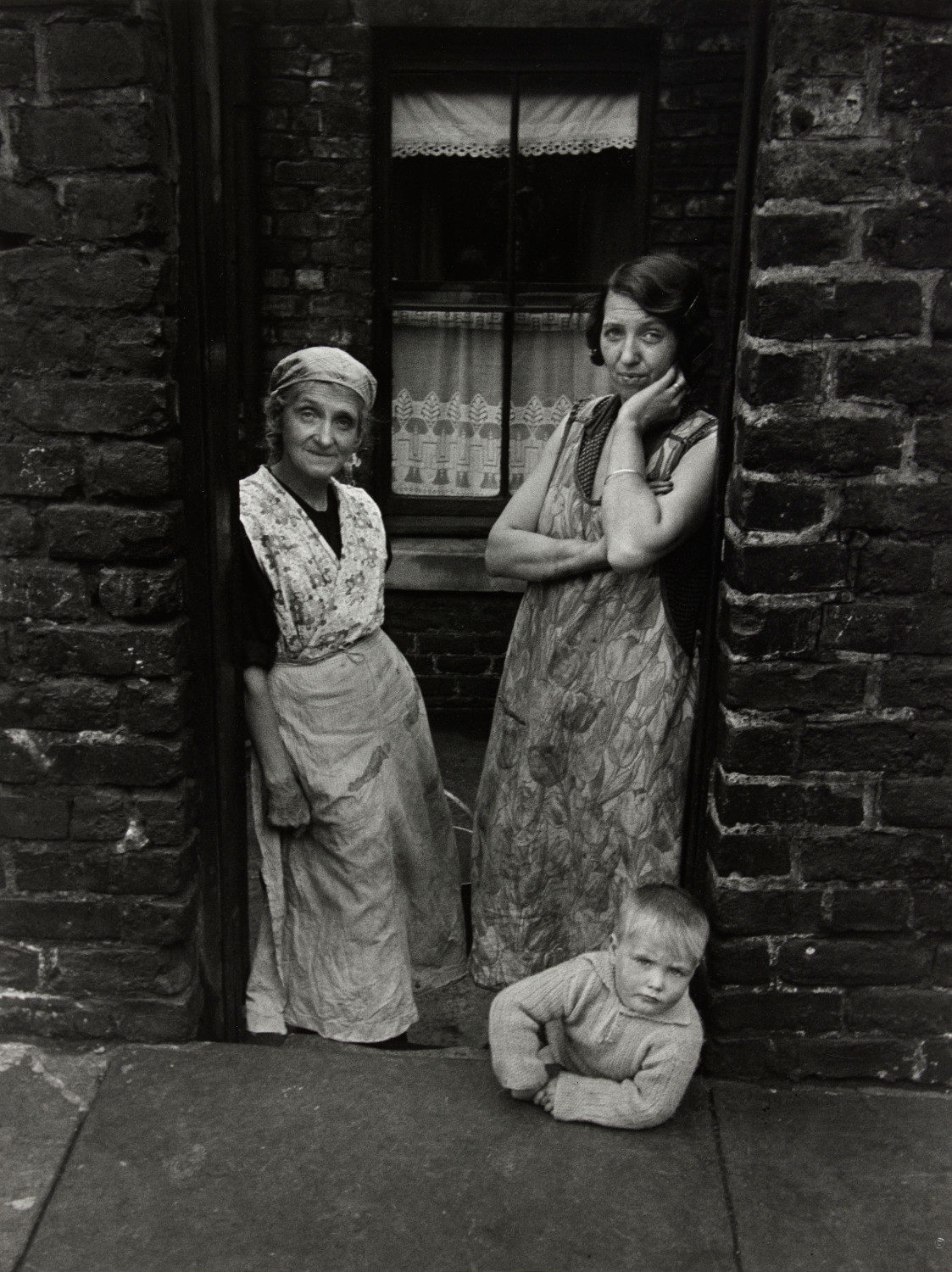

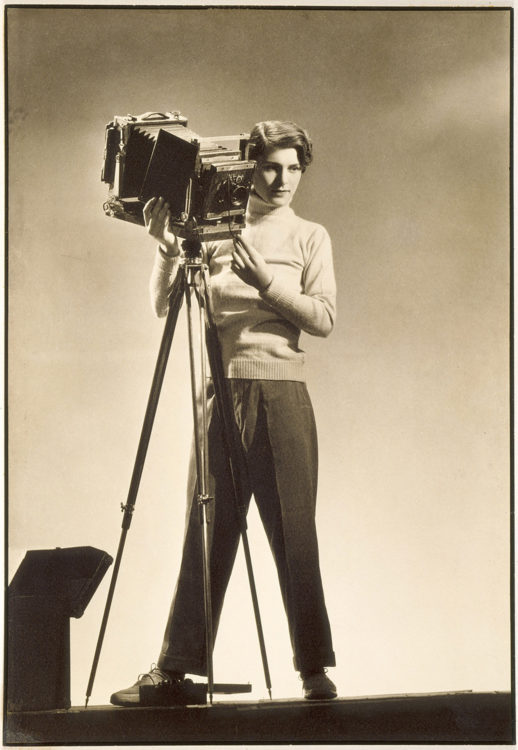

Born to a bourgeois German Jewish family, Gisèle Freund received her first camera from her father, who was an art collector. She enrolled in a school for children of industrial workers against the wishes of her family, and then studied sociology and the history of art in Freiburg and later Frankfurt in hopes of becoming a journalist. She decided to devote her doctoral research to the commercialisation of photographic portraiture in France in the nineteenth century. A member of the Socialist Youth in Frankfurt and fearing persecution, she fled to Paris in 1933. She began her work as a portraitist at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, where she continued her dissertation. In 1935, she became friends with Adrienne Monnier, and met the French and ex-patriate writers who frequented Monnier’s bookshop on the Rue de l’Odéon. She realised a series of photographs of James Joyce in his daily life, one of which was used for the cover of Time magazine after the publication of Finnegans Wake (1939). Although she obtained French citizenship through marriage, she was forced to flee France during the occupation. She moved to Buenos Aires and later travelled throughout Latin America to realise photo reportages. At the end of the war, she returned to Paris and signed a contract with the Parisian agency Magnum in 1947. She returned to Latin America for work on Patagonia and a series dedicated to Eva Peron before moving to Mexico for two years. There, she met Frida Kahlo and realised photographs of her and her peculiar world.

In 1952, the photographer returned to Paris permanently. She reconnected with writing and published the classic book Photography and Society (1974), in which she addressed questions of representation, the status of the trade and the transformations wrought by technological advances. Essentially self-taught, G. Freund had little interest in techniques and experimentation, instead relying on her curiosity and alert mind. Unlike the aesthetic of photographic portraiture in the magazines at the time (the “Harcourt” style), her photos were not retouched. Like a patina of time, the dominant amber of the film makes her figures feel closer and more fragile. A loyal follower of the psychology of the model, advocated by Nadar, she became imbued with the work of the artists that she photographed. For her, the “decisive moment” was the self-forgetfulness that reveals an unknown trait of the subject itself. If images like those of André Malraux or Virgina Woolf became emblematic because of a slight detail that captured the spirit of the artist, other images of artists in their workplace created an interior ambiance through particular framing, such as Pierre Bonnard on a bench in front of his house, or Henri Matisse absorbed by his drawings. Although she did not spare her efforts for the recognition of photography as an art in its own right, she rather considered herself a witness of her own time. As with her reportages, her portraits demonstrate the same spirit of justice, the same simplicity and complicity with her subjects. She considered portraiture a form of reportage. In 1957, the artist returned to Berlin to photograph the destruction caused by the war and the reconstruction of the city, then, after the construction of the wall in 1962, to document the daily life of East and West Berliners. Twenty years after the wall fell, Berlin paid homage to the artist by exhibiting her photographs of a world of changing landmarks, where life outweighs destruction. Her body of work, well-known after the 1960s through several distinctions and numerous exhibitions throughout the world, remains in the cultural memory as that of a cosmopolitan intellectual who knew how to anticipate the developments of photography and its influence on our visual culture. Shortly before her death, she left a large number of photographs to the French state, and her archives were acquired by the Washington State University Libraries manuscripts collection.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Gisèle Freund interview in 1985

Gisèle Freund interview in 1985