Gwen John

Roe Sue, Gwen John: A Life, London, Chatto & Windus, 2001

→Langdale Cecily, Gwen John : with a catalogue raisonné of the paintings and a selection of drawings, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1987

→Jenkins David Fraser & Stephens Chris (ed.), Gwen John and Augustus John, exh. cat., Tate Britain, London; National Museum & Gallery, Cardiff (2004 – 2005), London, Tate Publishing, 2004

Gwen John, paintings and drawings from the collection of Quinn & others, Stanford University Museum of Art, Stanford, 27 April – 27 June 1982

→Gwen John and Augustus John, Tate Britain, London; National Museum & Gallery, Cardiff, 2004 – 2005

→From Victorian to modern : innovation and tradition in the work of Vanessa Bell, Gwen John and Laura Knight, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham; Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne; Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Norwich, 2006 – 2007

British painter.

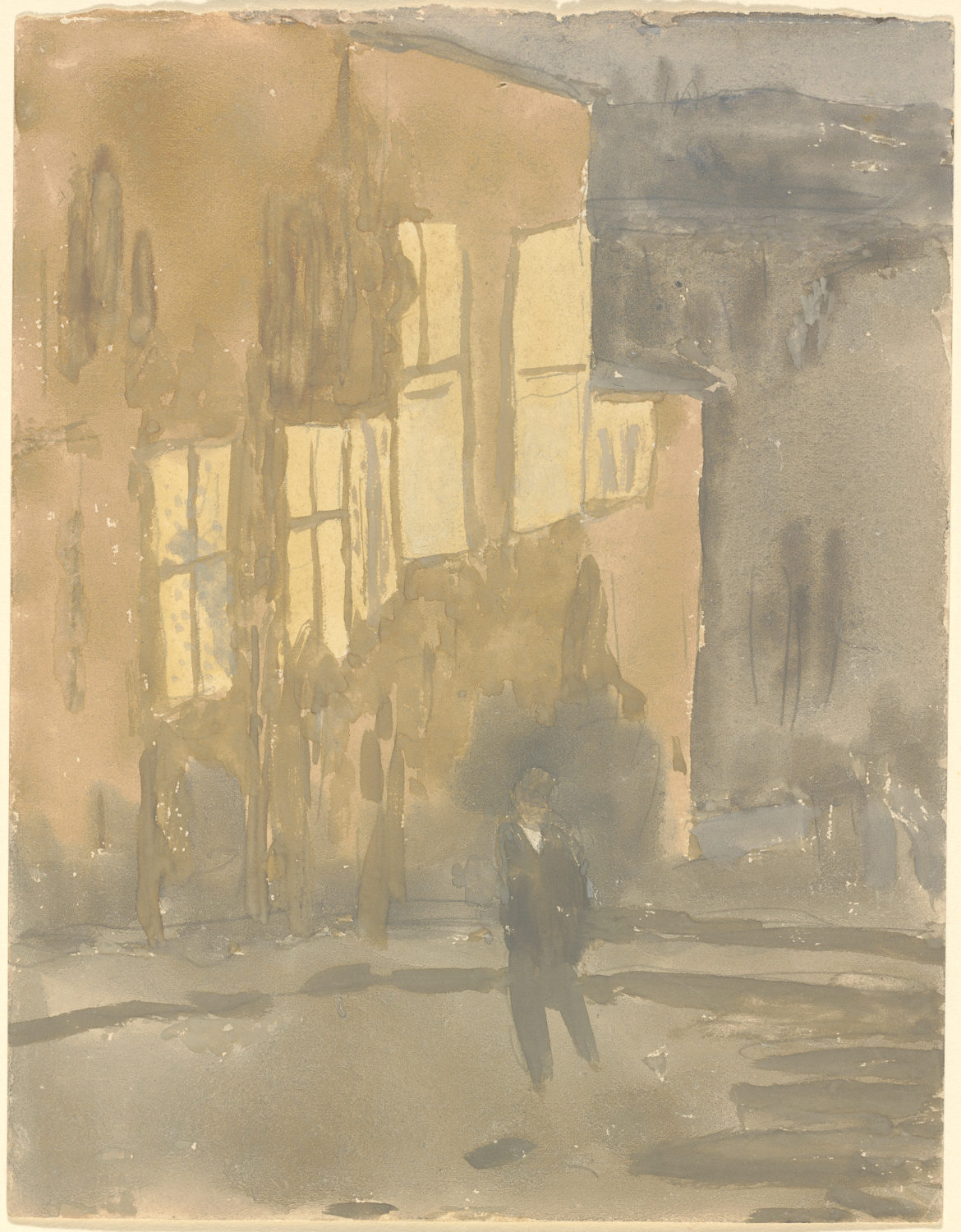

Through her independence, her decision to live alone in Paris, her solid training, and the importance of her female friendships, Gwen John seemed to be the model of a new type of woman at the end of the 19th century. Born to a mother who was an amateur painter and a father who was a legal advisor, she was the second of four children. Between 1895 and 1898, she attended courses at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London, growing up amid a small group of students, which included the future painters Edna Clarke Hall (1879-1979) and her great friend Ursula Tyrwhitt (1878-1966). In the winter of 1898, with Ida Nettelship (1877-1907) and Gwen Salmond, she studied at the Carmen Academy in Paris, where Whistler was teaching. In 1900, she came to notice through the qualities of Portrait of the Artist, a painting presented at the New English Art Club (NEAC). In 1903, together with her brother, she exhibited at the Carfax Gallery, then in the company of her friend Dorelia Mc Neill (1881-1969), she walked from Paris to Toulouse, living off the sale of her drawings. Two paintings from that period record her intentions: in L’Étudiante (1903), Dorelia, holding a book, is standing beside a table on which is laid Custine’s book, La Russie en 1839; Dorelia by Lamplight à Toulouse (1903-1904) shows the model engrossed in reading Custine’s book. The artist thus broke with the classical depiction of the fragile young girl, and showed us active young women of a new century. In 1904, she settled for good in Paris. In her pictures with their subtle shades of colour, she painted usually empty interiors, such as A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris (1907-1909), or at times rooms occupied by a woman alone, such as the Portrait of Chloe Boughton-Leigh (1907). To earn her living, she posed as a model, in particular for Rodin, and met many Montparnasse artists: Rainer Maria Rilke, Brancusi, Matisse, Picasso, Ida Gerhadi (1862-1927), and Hilda Flodin (1877-1958). She lodged temporarily with Mary Constance Lloyd (1859-1898), a painter and designer with whom she would remain in touch throughout her life. In 1908, the Portrait of Chloe Boughton-Leigh, presented at the NEAC, brought her to the attention of the critics.

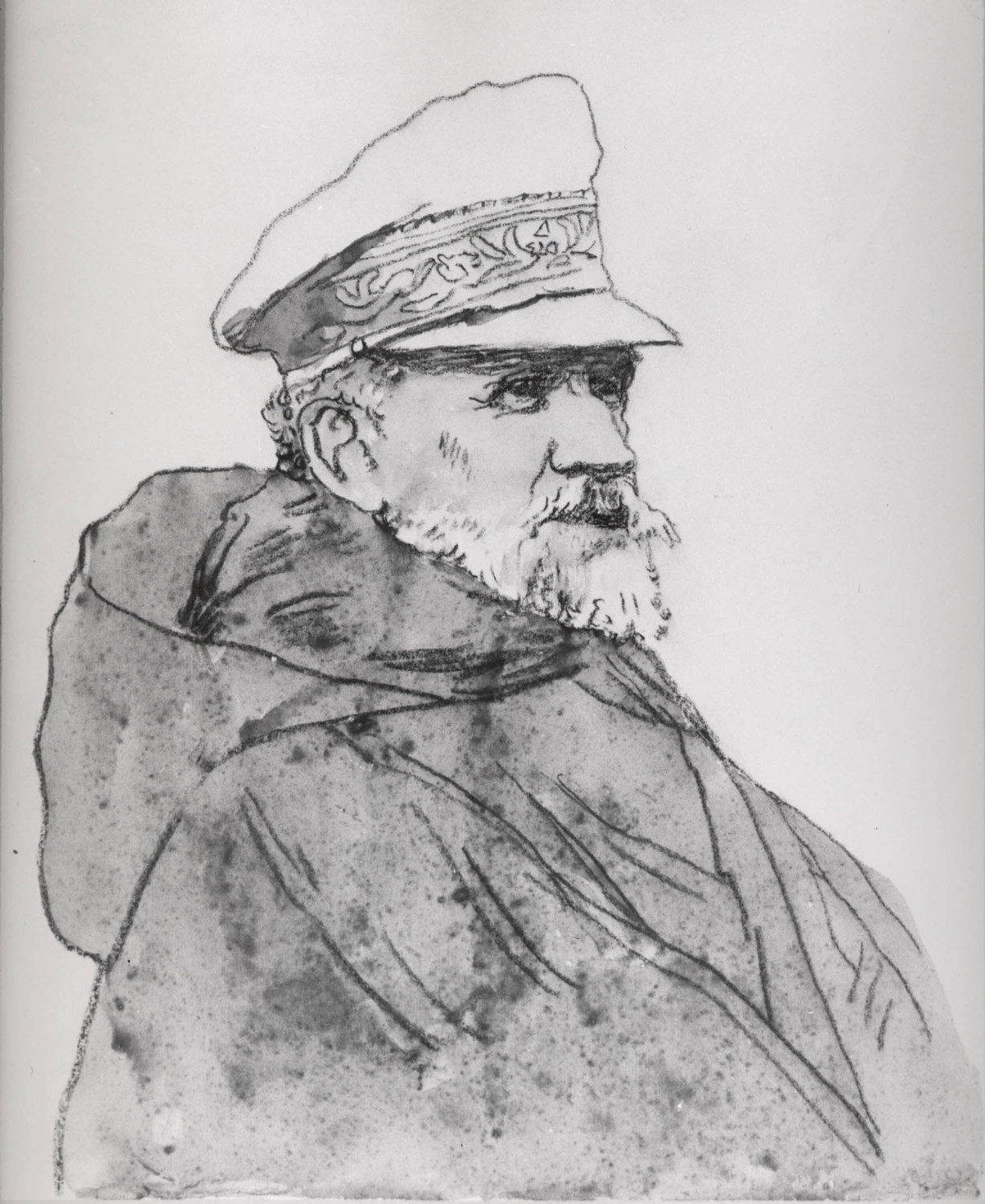

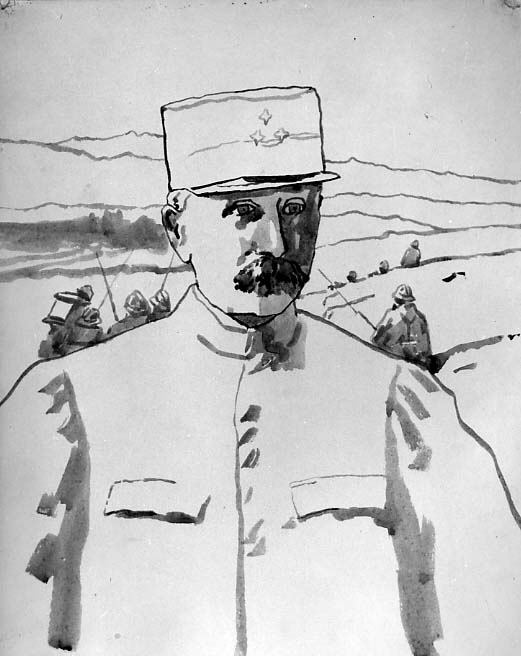

In 1910, she embarked on a correspondence with the American art collector, John Quinn, who asked her advice to enlarge his collection. Her very open way of looking at modernity harbingered her liking of the Futurist exhibition in 1912. In 1911 she moved to Meudon, keeping her Paris room as a studio. Two of her works were purchased by the Society of Contemporary Art in London, and, in 1913, the canvas titled Girl Reading at the Window, which she had sold to Quinn, was shown at the Armory Show in New York. That same year, after lengthy reflection, she converted to the Catholic religion; she then began a series of portraits of Mother Marie Poussepin (1653-1744), and devoted all her energy to duplicating and repeating one and the same motif. In 1919, at the Salon d’Automne, she exhibited nine drawings and a painting of Poussepin, then, from the following year onwards, her work was regularly present in the three Paris salons. In exchange for her works, Quinn paid her a regular private stipend, which meant that she no longer had to work as a model. In 1922, five of her works belonging to the collector were shown in the exhibition English Modernists at the Sculptors Gallery in New York. In 1924, she exhibited at the Salon des Tuileries, without passed in front of the jury. When Quinn died, his heir, his sister Julia Quinn, purchased five paintings by the artist, and constantly championed her work. In 1926, her canvases on view at the New Chenil Galleries were spotted by the art critic and curator Mary Chamot, who wrote an article about her. Between 1920 and 1930, she spent time in the reading room of the Grands magasins du Louvre, and produced a series of drawings of its regular visitors. From 1930 on, her output lessened a great deal, undoubtedly for health reasons and her ever more defective eyesight. In 1936, however, still deeply interested in modernity, she attended the classes of André Lhote. When war broke out in 1939, John died in Dieppe: she was trying to make her way to England.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

The contemplative art of Gwen John

The contemplative art of Gwen John

![Paroles d’artistes femmes [Words of Women Artists], 1869-1939 - AWARE](https://awarewomenartists.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/anthologie-1-aware-women-artists-artistes-femmes-1-750x509.webp)