Hanh Thi Pham

Kim, Elaine H, “‘Bad Women’: Asian American Visual Artists Hanh Thi Pham, Hung Liu, and Yong Soon Min,” Feminist Studies 22, no. 3 (1996), pp. 573–602

→Kuroda, Raiji (ed.), Asian Art Today: Fukuoka Annual X. Hanh Thi Pham: A Vietnamese, her Body in Revolt, exh. cat., Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, (February 4–30 March, 1997) Fukuoka, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, 1997

→Machida, Margo, Unsettled Visions: Contemporary Asian American Artists and the Social Imaginary, Durham/London, Duke University Press, 2009

Asian Art Today: Fukuoka Annual X. Hanh Thi Pham, Vietnam X America: Her Body in Revolt, Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, 4 February–30 March, 1997

→Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian American Art, The Asia Society Galleries, New York City, 16 February–26 June, 1994; Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma 1 October–27 November, 1994; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 26 February–21 May, 1995; Honolulu Academy of Fine Arts, Honolulu, 2 August–3 September, 1995; Center for the Arts at Yerba Buena Gardens, San Francisco, 1 October–10 December, 1995; MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge (Massachusetts), 13 January–28 July, 1996

→A Different War: Vietnam in Art, Whatcom Museum of History and Art, Bellingham, 19 August–12 November, 1989; De Cordova Museum and Sculpture Park, Lincoln, 17 February–15 April, 1990; Mary and Leigh Block Gallery Northwestern University, Evanston, 9 May–24 June, 1990; Akron Art Museum, Akron, 8 September–4 November, 1990; Madison Art Center, Madison, 1 December, 1990–27 January, 1991; Wight Art Gallery, UCLA, Los Angeles, 24 March–19 May, 1991; Museum of Art Washington State University, Pullmann, 13 January–23 February, 1992

Vietnamese-American visual artist.

Hanh Thi Pham left Vietnam in 1975, the final year of the Second Indochina War (otherwise known as the Vietnam War). Her family settled in Orange County, California, home to the largest diasporic Vietnamese community in the United States. H. T. Pham gained work in commercial photography, which led to her earning an MFA from California State University, Fullerton, in 1986. She subsequently developed an activist artistic practice combining theatrical narrative, performance, and photography. Strongly informed by traumatic memories of war in Vietnam, the United States-centric narrative of the war, and her subjectivity as an immigrant and lesbian, H. T. Pham saw her art as a powerful means of responding to both the racialised and gendered stereotypes of Vietnamese in American representations of the war, and the patriarchal conservatism of the Vietnamese refugee community in California. Using confrontational language and imagery, typically featuring the artist herself, her work speaks to these issues and asserts the complexities of the artist’s identity against cultures of silence and marginalisation.

In the 1980s Pham addressed the jarring social and psychological effects of the refugee experience, using multiple exposure photography to stage herself within allegorical tableaux depicting loss, confusion and displacement, such as in the Post-Obit/Series 1 (1983). A subsequent project with California-based American sculptor Richard Turner (b. 1943), Along the Street of Knives (1985), comprised eight large-scale colour photographs in which the two artists – both of whom had lived in Vietnam in their youth – performed semi-autobiographical scenes where they embodied figures of the politico-cultural antagonisms and misunderstandings that characterised Vietnam-United States relations. For Pham, the photographic narrative form was intended to portray a multiplicity of perspectives and subject positions, with the hope of stimulating dialogue and communication in an atmosphere in which communities on both sides of the Vietnam-United States conflict muffled dissent to hasten performative resolution.

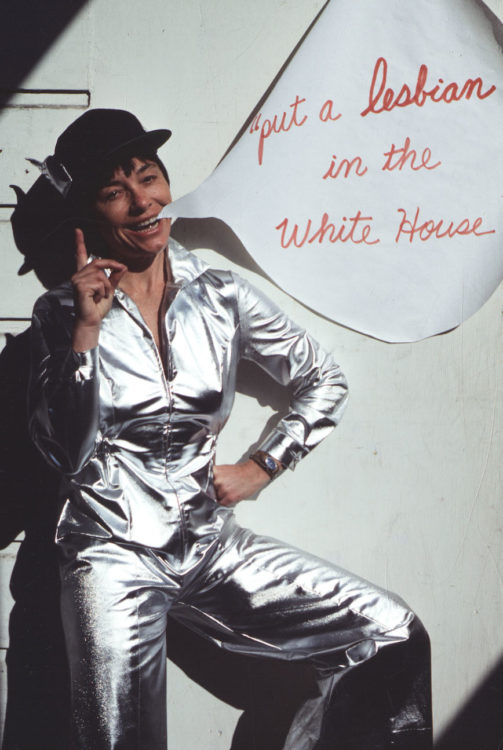

H. T. Pham often inhabited stereotypical images of Vietnamese femininity (wearing the traditional áo dài) or resistance (the communist guerrilla) to create provocative and critical commentary. In several series from the 1990s, she subverted symbolic iconography and used language more prominently to assert self-empowerment as a queer displaced subject, and to address more widespread issues about patriarchy, race and sexuality. She reconfigured the traditional family portrait in the photomontage series Reframing the Family (1990–1991), from a revised portrait of her own family in which her mother had been excluded, to other images embracing queer intimacy and family relationships. In Misbegotten No More, from the series Expatriate Consciousness (Khong la nguoi o) (1991–1992), the bare-breasted artist makes an obscene gesture toward a vertical panel of text that reads (from the bottom up) “Không là người ở”, which connotatively translates as “Not your servant”. Her flexed arms are juxtaposed against an inverted, crossed-out image of Buffalo Bill Cody, a historical symbol of the violence of American westward expansionism. In a particularly powerful statement about sexual sovereignty and self-governance, the mixed media installation Lesbian Precepts (1992–1994) reinvents traditional Christian and Buddhist symbolism to centre the artist’s nude body as a figure of transexual identity and site of knowledge and acceptance.

A biography produced as part of the programme The Flow of History. Southeast Asian Women Artists, in collaboration with Asia Art Archive

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2024