Hannah Höch

Honisch Dieter, Marschall von Bieberstein Michael et Pagé Suzanne (ed.), Hannah Höch : collages, peintures, aquarelles, gouaches, dessins, exh. cat., Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (30 January–7 March 1976); Nationalgalerie Berlin, (24 March–9 May 1976)

Hannah Höch, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 1974

→Hannah Höch : collages, peintures, aquarelles, gouaches, dessins, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 30 January–7 March 1976; Nationalgalerie Berlin, 24 March–9 May 1976

→The Photomontages of Hannah Höch, The Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 1997

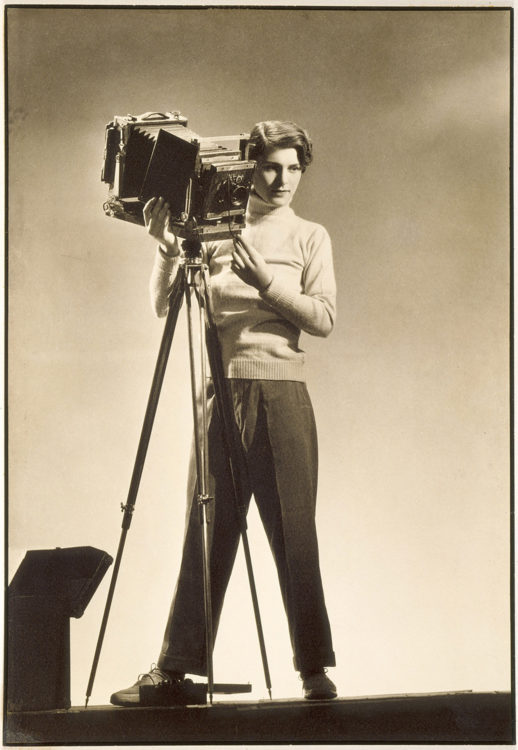

German visual artist.

Hannah Höch was the eldest of five children born to a provincial family. In 1904, her family made her leave school to take care of her younger sister, thus postponing the art studies she had intended to follow. Instead, she practiced watercolours and drawing, using the surrounding countryside and family members as models. She finally began attending the Charlottenburg School of Applied Arts in 1912. She learnt glass drawing under the direction of Harold Bengen and calligraphy with Ludwig Sütterlin. The school closed when the war was declared, and the young student left to work for the Red Cross in Gotha. She returned to Berlin the following year and studied graphics under the artist Emil Orlik. There she met Raoul Hausmann, with whom she would have an extramarital affair until 1922. From 1916 to 1926, she worked for the Ullstein Press, designing crochet and knitting patterns for their magazines, which provided her with endless resources for her photomontages. She used fragile papers, most of which can be found in her collages from 1920 onwards. During a holiday on the Baltic Sea in 1918, the artist and Haussmann discovered the popular custom of gluing a photograph of one’s own face on pictures of Prussian soldiers—this would become an inspiration for their first Dadaist collages. Höch became friends with Hans Arp and Kurt Schwitters, took part in the November Group’s meetings and sporadically in their annual exhibitions. She also became an active participant in Dada events in Berlin as from 1919.

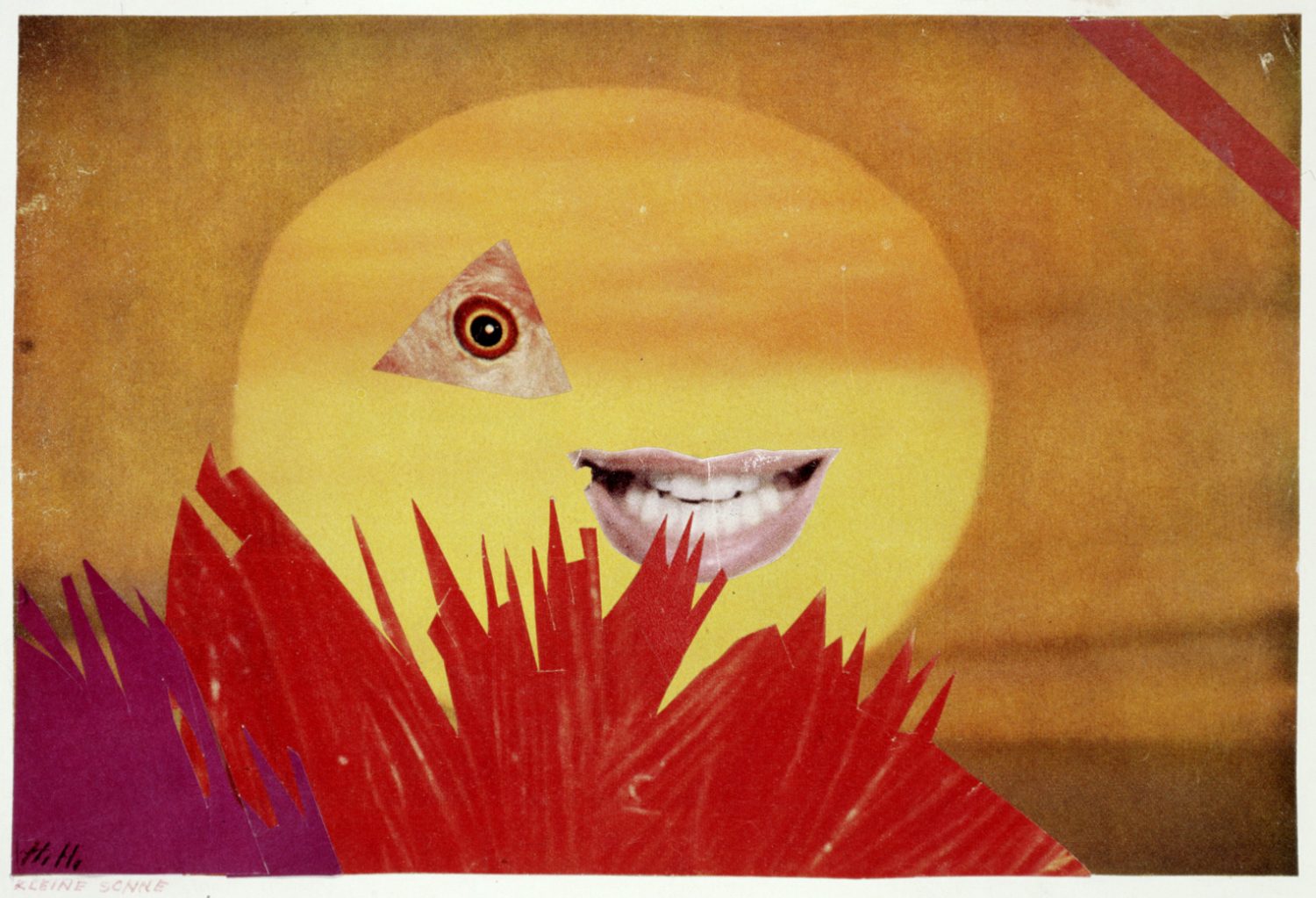

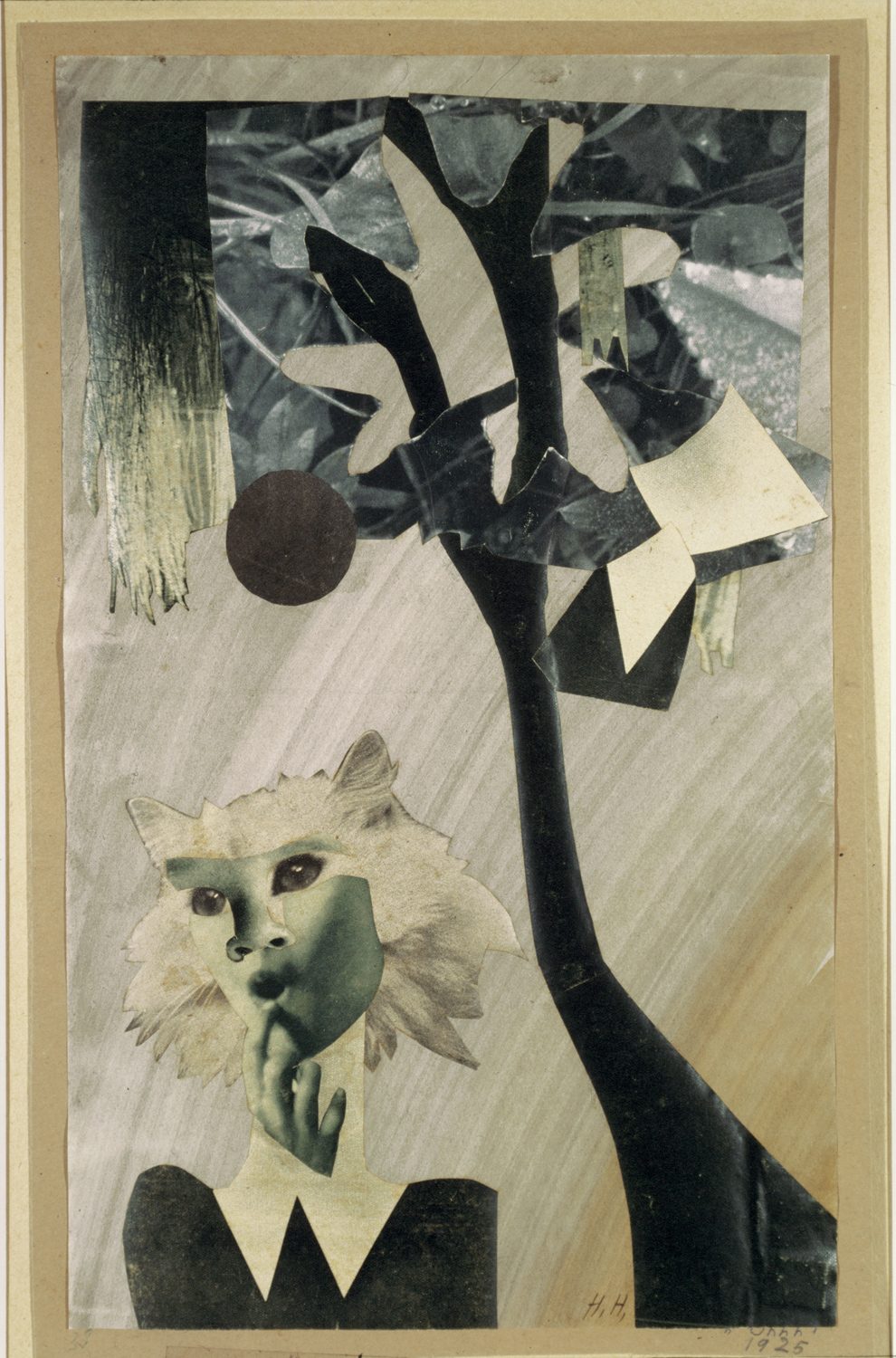

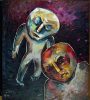

In 1920, the review Schall und Rauch featured the outlines of two of her dolls on its cover. Despite George Grosz and John Heartfield’s reticence to accept a female artist, she showed two major pieces at the First International Dada Fair: Dada-Rundschau [Dada-Review, 1919] and Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands [Cut with the Dada kitchen knife through the last beer-belly cultural epoch in Germany, 1919–1920]. In addition to the main political figures of the Weimar Republic, it already contains the theme of the identity and social role of women, which she would develop during the following years. The artist attended Arthur Segal’s Monday sessions, where she rubbed shoulders with Ernst Simmel, Erich Buchholz, and Alfred Döblin. With one of her sisters and the Swiss poet Regina Ullmann (1894–1961), she set out partly on foot on a journey to Rome. The result of the experience was Roma (1925), a painting in which the actress Asta Nielsen (1881–1972) dismisses Mussolini with a wave of her hand. Between 1920 and 1930, she began to exploit different materials and techniques, and in doing so created a series of major works: a collection of ethnographic collages and a considerable number of symbolic landscapes.

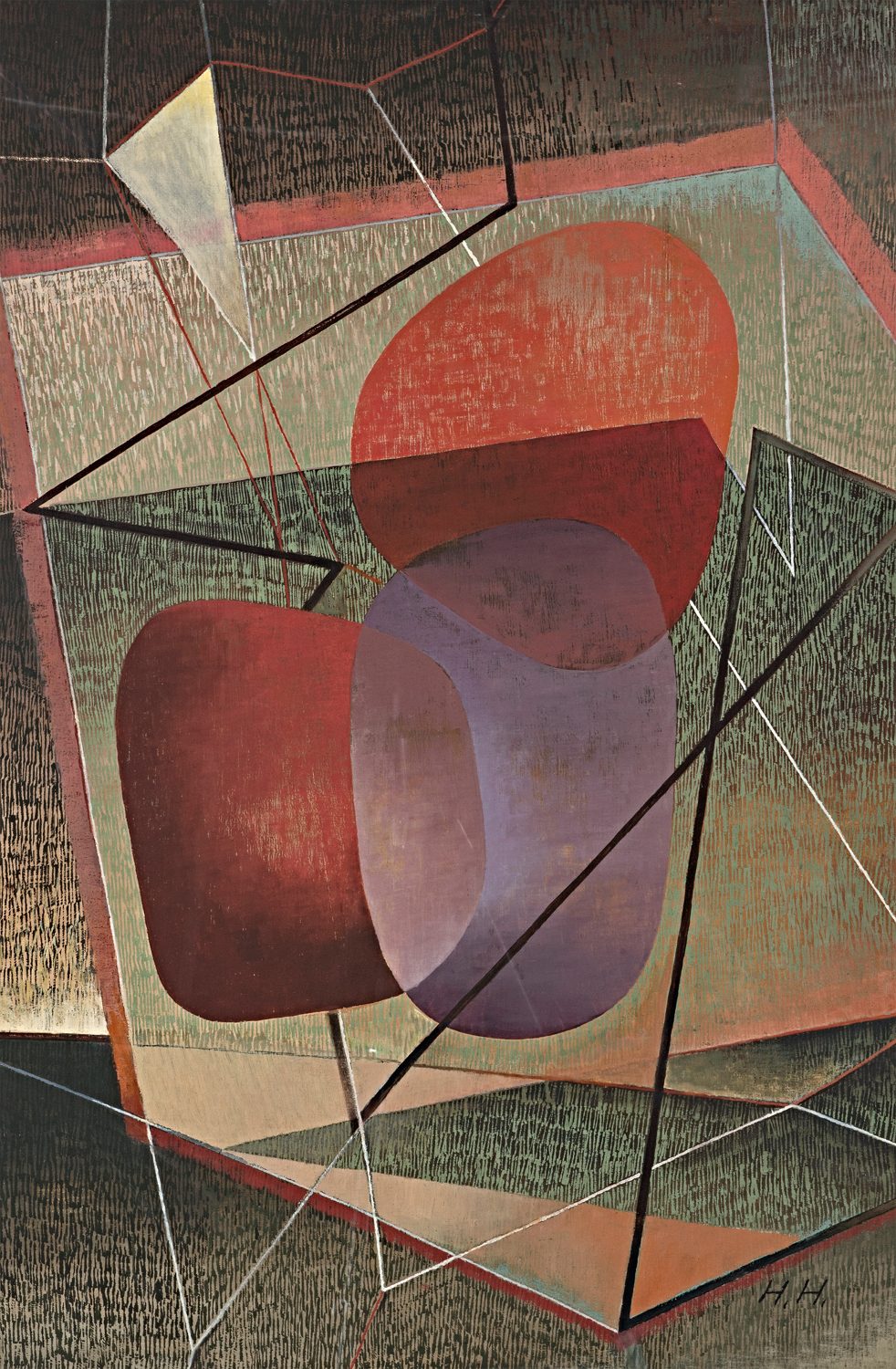

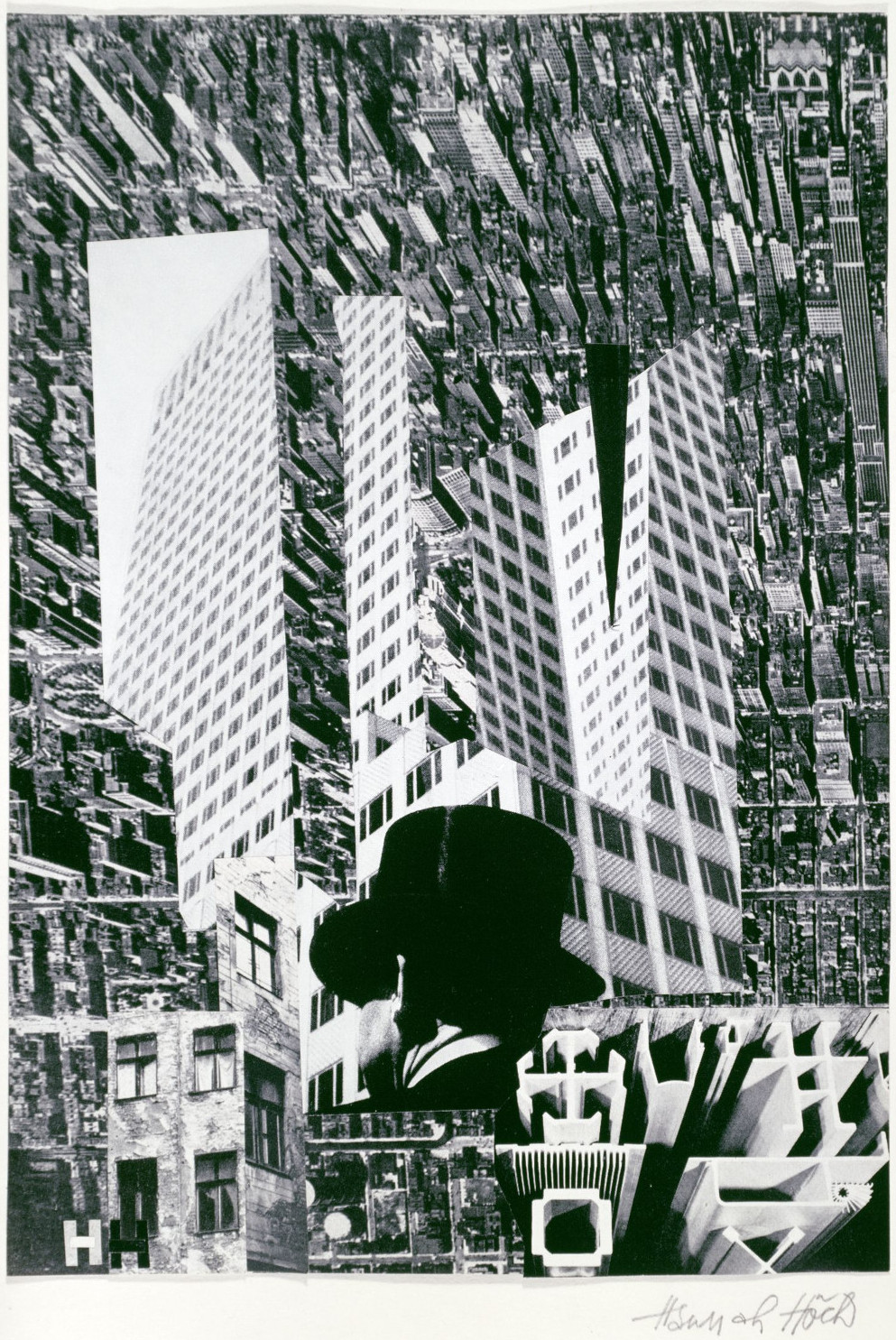

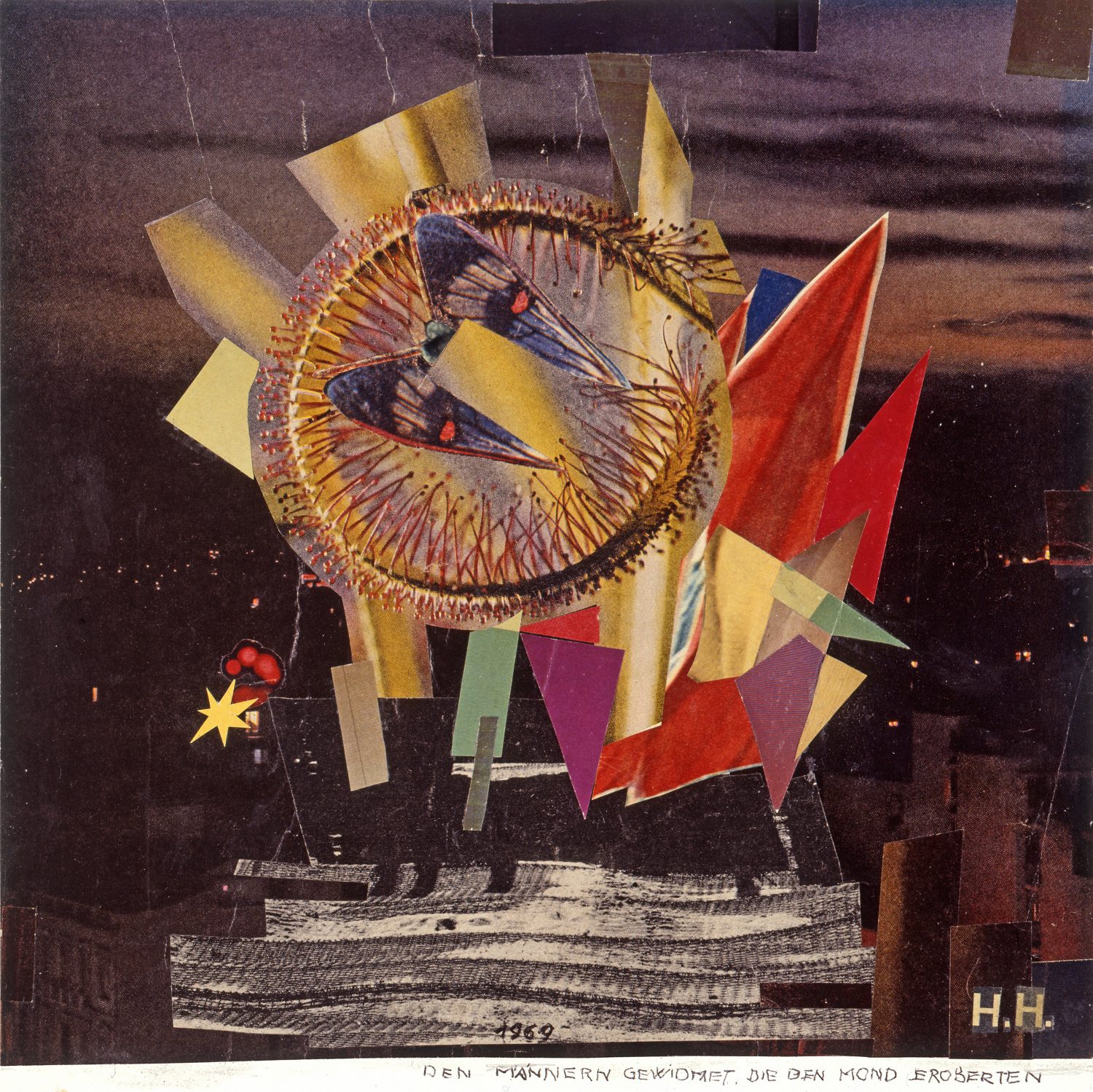

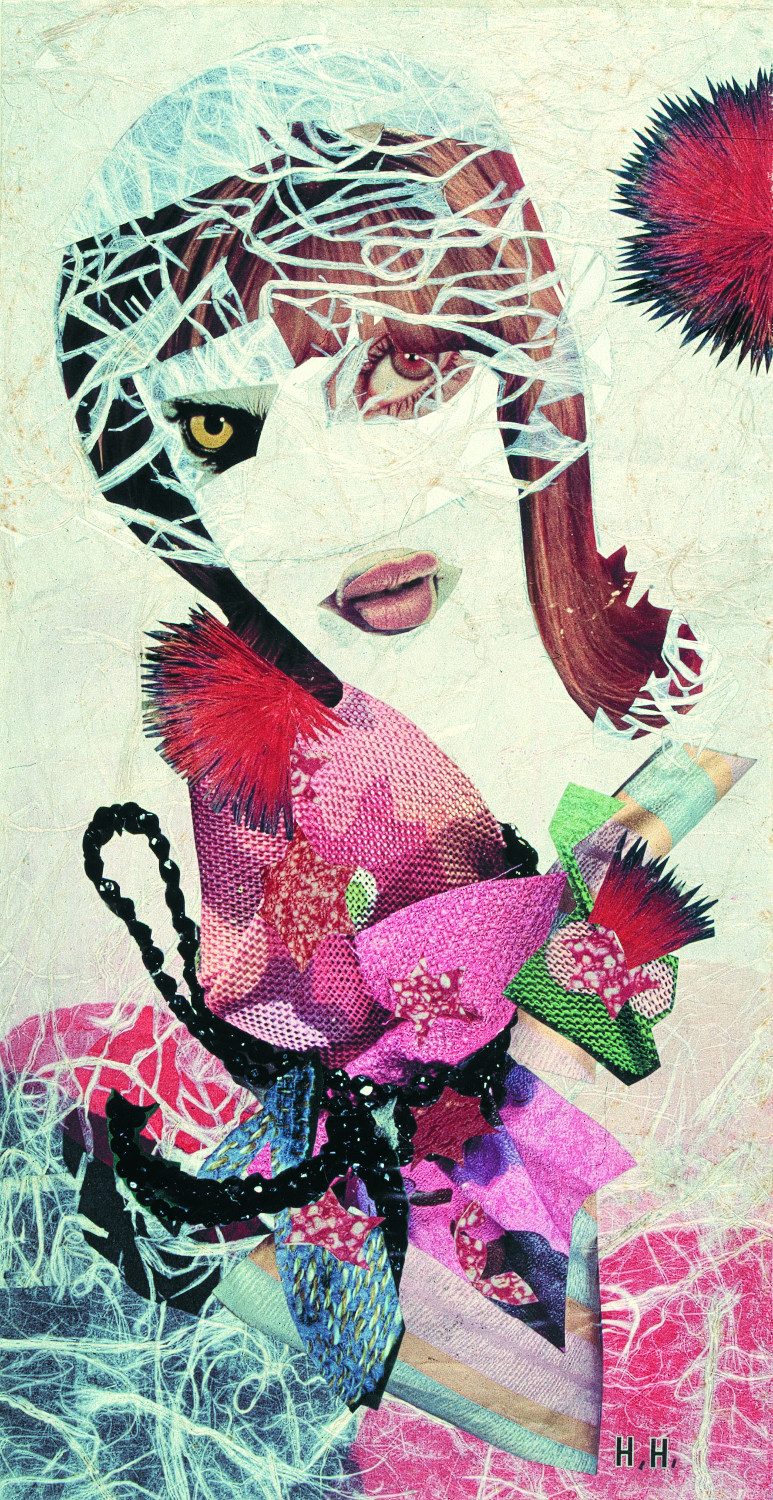

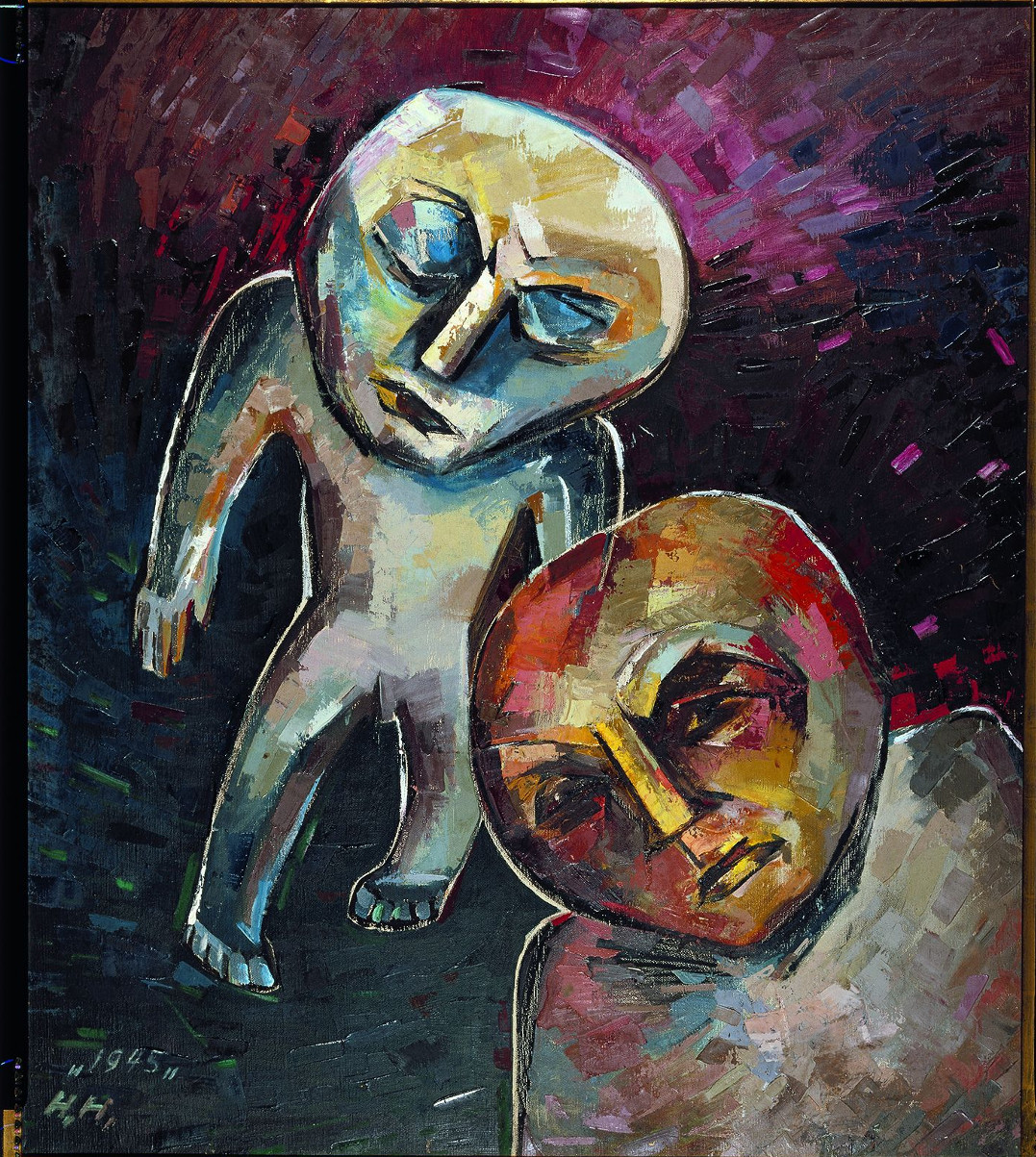

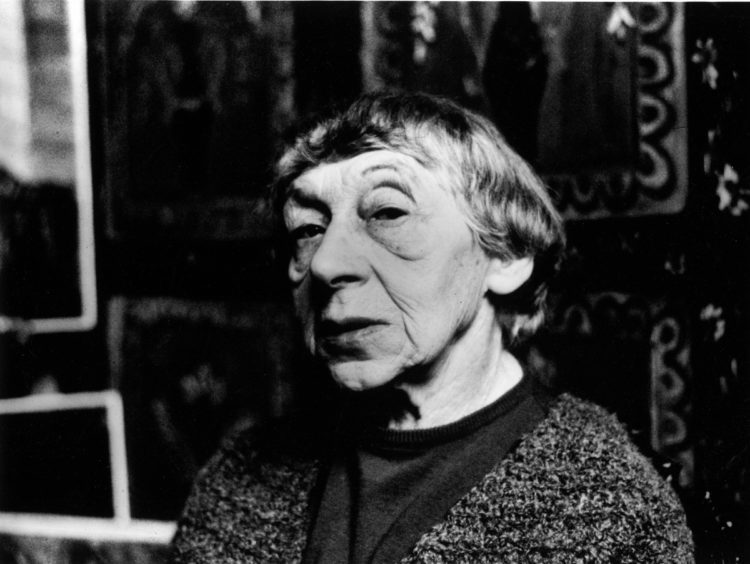

Her photomontage work parodied bourgeois life and explored the new expressions of femininity very common in media culture in the interwar period, while also enabling her to deconstruct the notions of race and sexual identity by creating hybrid faces. She used feminine everyday objects—ribbons, buttons, pieces of fabric, and lace trimmings—which she then deformed until they became grotesque or menacing. She transferred the principle of montage to the field of painting, reworking some of her earlier pictures by adding new elements to them. In 1926, she met the Dutch writer Til Brugman (1888–1958), who would become her partner until 1935. She made contact with the De Stijl Group, became acquainted with Mondrian and Theo and Nelly van Doesburg (1899–1975), and joined the Onafhankelijke. She spent the war years living alone near Berlin, hiding metal crates in her garden that contained works by Hausmann, Arp, Schwitters, and her own, as well as catalogues, letters, reviews and documentaries from the Dada period. She gradually began working again in 1947 with oil paints and collages, in which colour photographs can be seen for the first time. The Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin held major retrospectives of her work in 1976. The artist died two years later.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Hannah Höch exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Hannah Höch exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris