Focus

Dora Maar, Untitled [Shell-Hand], ca. 1934, silver print on flexible media, 23.4 x 17.5 cm, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, © ADAGP, Paris

The Surrealist group formed in Paris in 1924 around André Breton. Published that same year, the Surrealist Manifesto defined the movement as a “pure psychic automatism by which it is intended to express, either verbally or in writing, the true function of thought”. At the beginning the group was exclusively composed by men – women were only present as muses or lovers. Objects of male, heterosexual desire, they saw themselves as confined to representations of women as children, femme-fatales or hysterics, in order to stimulate the imagination of men who surrendered themselves to the power of the subconscious. Yet, the politically and socially engaged Surrealists rejected tradition – marriage, children, family – and wanted to use art as a means of reorganising society. This subversive movement in search of freedom thus attracted a number of women artists.

It was not until the 1930s that female artists grasped the Surrealist language, which sought to reduce the role of consciousness and the intervention of the will through the introduction of new techniques and forms of creation. Jacqueline Lamba (1910-1993) and Valentine Hugo (1887-1968) participated in the production of cadavres exquis, or exquisite corpses, collaborative artworks that gave way to chance. Meret Oppenheim (1913-1985) with Le déjeuner en fourrure (Breakfast in Fur, 1936) and V. Hugo with Objet à fonctionnement symbolique (1931) conceived surrealist objects – assemblages that played with ambiguity, fetishization and the poetic value of objects.

Certain women artists appropriated the power of desire and of dreams. Toyen (1902-1982) realised erotic illustrations and magical paintings that appeared in her intimate visions. The work of Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012) was based on hallucinations between anxiety and sexual fantasy. Photographers also explored the possibilities of distorting reality. Lee Miller (1907-1997) manipulated images through solarisation and photograms, whereas Dora Maar (1907-1997) created photomontages with strange compositions, traces of fascination for the horrible and the shapeless.

Other artists turned away from the usual Surrealist repertoire in order to reaffirm their own identity and independence. Amongst them, Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) used animal symbolism to express her desire for freedom and to place herself within a matriarchal lineage. Through self-portraiture, Claude Cahun (1894-1954) questioned gender stereotypes, the multiplicity of identity and androgyny. In her paintings, Leonor Fini (1908-1996) unveiled male nudes in which the men became the objects of the female gaze. These reversals of perspective materialised critiques of male dominance within both the movement and society.

Women’s contributions to Surrealism was much more significant than what has been taught in art history. Beginning in the 1930s, they participated in exhibitions such as Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism at MoMA in New York in 1936, as well as the Surrealist objects exhibition at the Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris that same year. It is thanks to these artists and their social networks that after World War II the movement developed beyond the Parisian circle, notably in the United States and Mexico, with figures such as Remedios Varo (1908-1963) and Frida Kahlo (1907-1954).

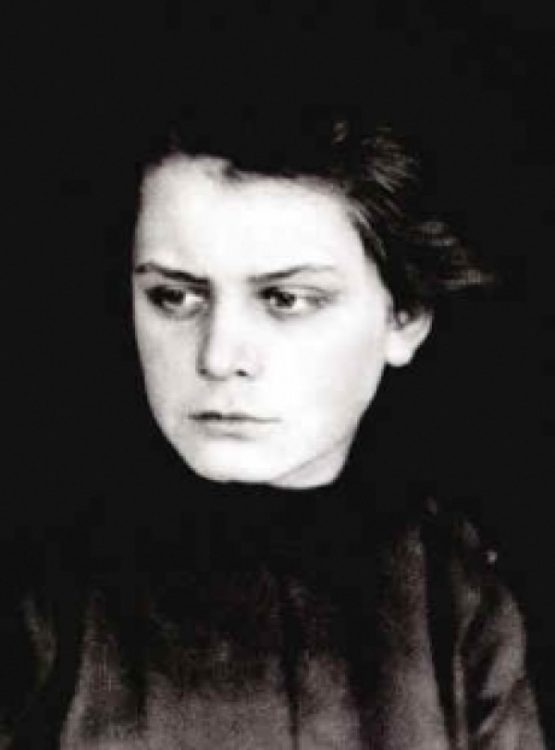

1894 — France | 1954 — Jersey

Claude Cahun

1917 — United Kingdom | 2011 — Mexico

Leonora Carrington

1907 — Argentina | 1996 — France

Leonor Fini

1907 — United States | 1977 — United Kingdom

Lee Miller

1907 — 1997 | France

Dora Maar

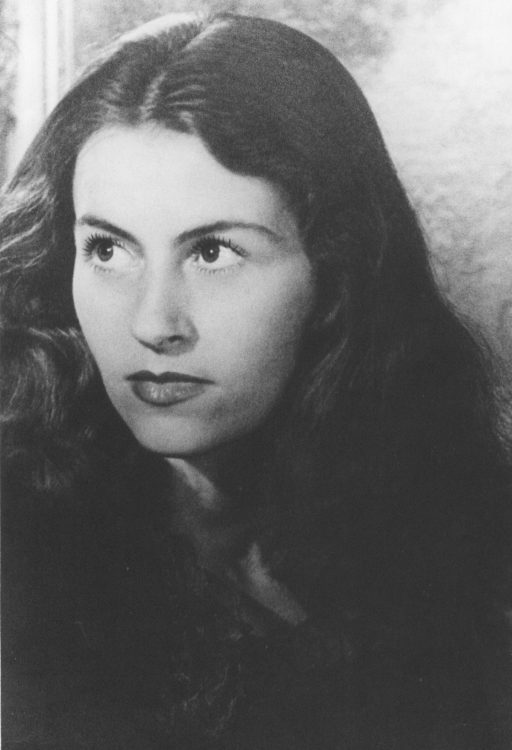

1910 — 1993 | France

Jacqueline Lamba

1913 — Germany | 1985 — Switzerland

Meret Oppenheim

1887 — 1968 | France

Valentine Hugo

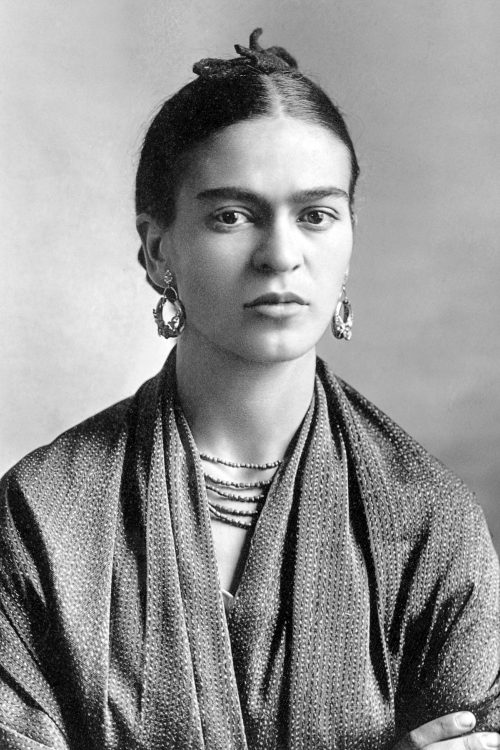

1907 — 1954 | Mexico

Frida Kahlo

1904 — France | 1987 — Mexico

Alice Rahon

1902 — 1955 | Mexico

María Izquierdo

1898 — France | 1978 — United Kingdom

Valentine Penrose

1899 — Argentina | 1991 — United Kingdom

Eileen Agar

1910 — 2012 | United States

Dorothea Tanning

1904 — Indonesia | 1971 — France

Christine Boumeester

1938 — 2016 | Croatia

Nives Kavurić-Kurtović

1902 — 1995 | Spain

Maruja Mallo

1894 — 1973 | Brazil

Maria Martins

1898 — Egypt | 1974 — France

Amy Nimr

1908 — Spain | 1963 — Mexico

Remedios Varo

1902 — Czech Republic | 1982 — France

Toyen (Marie Čerminová dite)

1898 — 1963 | United States

Kay Sage

1904 — Germany | 1999 — Argentina

Grete Stern

1916 — Germany | 1970 — France

Unica Zürn

1911 — Denmark | 1984 — France

Sonja Ferlov Mancoba

1923 — 2014 | Turkey

Tiraje Dikmen

1913 — 1994 | United States

Helen Phillips

1942 — 2008 | Argentina

Mildred Burton

1884 — 1982 | France

Juliette Roche

1889 — 1978 | Germany

Hannah Höch

1935 — Portugal | 2022 — Great Britain

Paula Rego

1906 — 1999 | United Kingdom

Emmy Bridgwater

1913 — 1991 | Japan

Yukiko (Yuki) Katsura

1920 — 1960 | Australia

Joy Hester

1940 — Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic) | 2005 — Czech Republic

Eva Švankmajerová

1956 — 2018 | Taiwan

YAN Ming-Huy

1939 | Egypt

Wissam Fahmy

1909 — 1976 | France

Roberta González

1911 — France | 2010 — United States

Louise Bourgeois

1908 — 1984 | United States

Lee Krasner

1923 — Hungary | 2020 — France

Judit Reigl

1985 — United States | 1970 — Mexico

Rosa Rolanda (Rosemonde Cowan)

1951 | États-Unis

Cindy Sherman

1911 — Switzerland | 1990 — France

Isabelle Waldberg

1958 — 1981 | United States

Francesca Woodman

1874 — Poland | 1927 — France

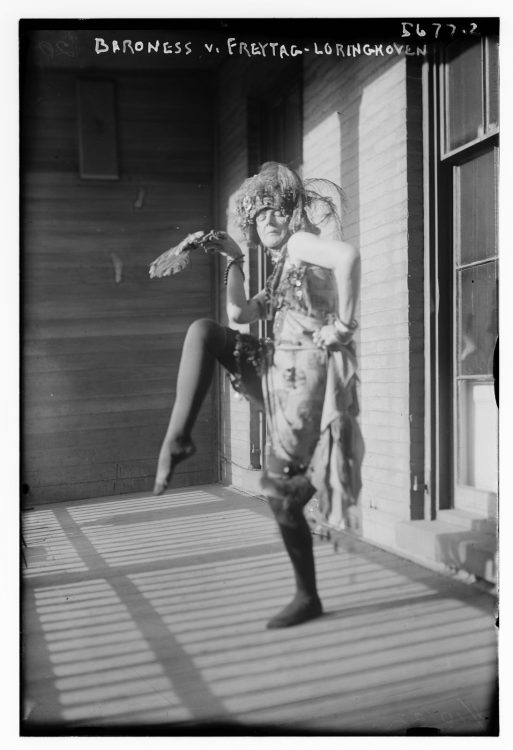

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

1930 — Sweden | 1995 — France