Research

In the 1920s and ’30s, Paris was considered the capital of the arts. From the ashes of World War I rose Surrealism, an artistic and literary movement that claimed to challenge the values of the narrow-minded and hypocritical bourgeoisie by declaring “total equality for all human beings”1, men and women alike.

However, this equality, which the poet André Breton defended in 1934, was in fact only theoretical. In reality, French Surrealism was not particularly fond of women, or, if anything, loved them as the objects of men’s desire: as muses, child-like entities, femmes fatales, or as the stereotype of the submissive or crazy woman. And yet, in the shadow of men, many women joined the movement, using their creativity to build an independent identity for themselves. But very few of them, especially in the interwar period, were recognised as artists in their own right, and most are still ignored by the critics to this day or are treated with more or less benevolent condescendence.

Franciska Clausen (1899-1986), Rita Kernn-Larsen (1904-1998), and Elsa Thoresen (1906-1994), all three from Northern Europe, were among the few women artists to be included in the international exhibitions organised under André Breton’s supervision. F. Clausen and R. Kernn-Larsen were featured at the kubisme = surrealisme exhibition in Copenhagen in 1935, and R. Kernn-Larsen and E. Thoresen at the International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris in 1938. During their time in Paris, all three artists were faced with the misogyny of the predominantly male group.

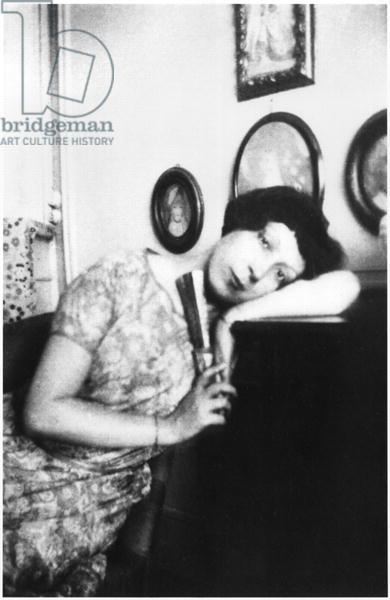

Danish artist F. Clausen was the first to make the journey, in 1924, precisely when the first issue of the magazine Révolution surréaliste was being published. After training at the Bauhaus, she went on to study painting, like many other women, at Académie moderne of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant. There, she met the Swedish painter Erik Olson, who, once converted to Surrealism, invited her to the kubisme = surrealisme event he had organised with the Danish painter Vilhelm Bjerke-Petersen. F. Clausen painted her first surrealist pictures in Paris. She was very close to F. Léger, who considered her one of his finest students, and took part in the 1925 exhibition L’art d’aujourd’hui, where she presented three pieces: a Landscape, a Still Life, and a Composition. At the event, she discovered the works of Jean Crotti, Max Ernst, André Masson, Joan Miró, and Toyen. Gradually distancing herself from the mechanical forms inspired by F. Léger, she painted Sommerfuglen [Butterfly, 1926], a dreamlike landscape open to multiple interpretations: it shows a gigantic eye tethered to the ground by long roots, floating in front of a roofless house with closed shutters; next to it, a butterfly flutters over a glass vial at the centre of the composition. The following year, at the Salon des Indépendants, F. Clausen exhibited Fisken (Désir de grossesse, 1926), a collage midway between Constructivism and Surrealism, in which a fish can be seen jumping out of the water amid geometric forms. She temporarily left the Surrealist movement to join the Cercle et Carré group in 1930, then returned to it when she moved back to Denmark in 1932 and took part in the exhibition kubisme = surrealisme.

Rita Kernn Larsen, Den vaeltede skuffe [The overturned drawer], 1931, oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm, © ADAGP, Paris

Rita Kernn-Larsen, La Pomme de la Normandie [The apple from Normandy], 1934, oil on canvas, 97 x 74 cm, © ADAGP, Paris

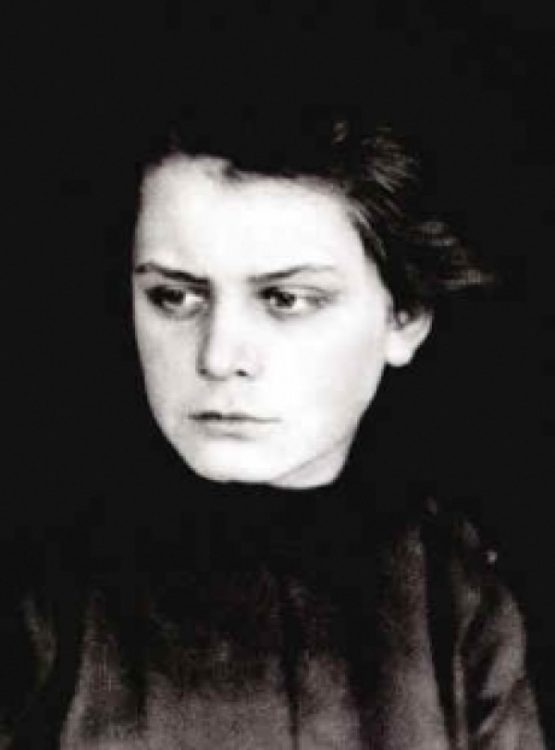

R. Kernn-Larsen spent time in Paris in 1929. Like F. Clausen, she took classes from F. Léger at the Académie moderne, where she studied composition. She developed a friendship with the Dadaist poet, writer and painter Georges Ribemont-Dessaigne and gradually distanced herself from F. Léger’s style by adding elements from her subconscious to her constructions (Den vœltede skuffe [The Overturned Drawer], 1931; La Pomme de la Normandie [The Apple from Normandy], 1934). Without her even noticing it, R. Kernn-Larsen’s painting began to present surrealist characteristics. However, it was only in 1934, after she had returned to Copenhagen, joined the Danish surrealist group (where she would meet Elsa Thoresen), and studied Freud, that her painting would become fully surrealist. R. Kernn-Larsen was among the very few women in the movement to introduce nude female figures into her work. Unlike the eroticised, idealised, and provocative images of her male counterparts, particularly her fellow countryman Freddie, her chaste and desexualised nudes act as a realistic point of reference in a dreamlike world, sometimes even depicted as rooted in the soil and turning into trees (Kvindernes oprør [The Women’s Uprising], 1940). Her return to Paris in 1937 was a turning point in her career. She met Peggy Guggenheim, who organised a solo exhibition of her work the following year in London. That autumn, she made a name for herself by showing eight pieces at the Salon des Superindépendants.2 Most importantly, she was one of the few women to be allowed into the very masculine circle of the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938, where she presented two pictures, Une Journée de plaisir [Delightful Day, 1937] and Selvportraet (kend dig selv) [Self-Portrait (Know Thyself), 1937], in which the artist is depicted reflected from behind in a mirror, watched over by her own eye. Her face is shown in its fragmented form, her nose hovering on the left side of the mirror and her mouth turning into a leaf shape beneath.

Elsa Thorensen, Verdenslyset [The light of the world], 1937, oil on canvas, 78.5 x 58 cm, © ADAGP, Paris

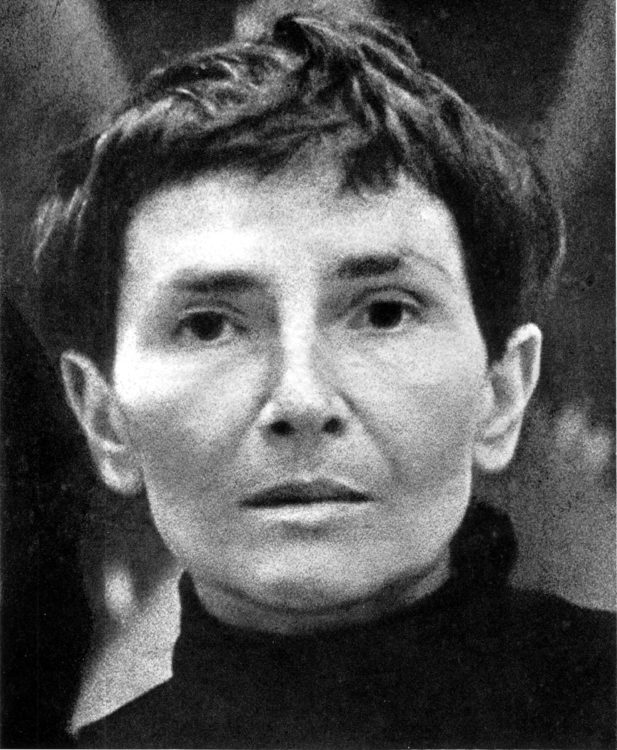

Shown close by were the works of her friend E. Thoresen, a member of the Danish surrealist group, who had just arrived in Paris with her husband Vilhelm Bjerke-Petersen. E. Thoresen presented two pictures: Verdenslyset [Light of the World, 1937] and Jeb ved det ikke [I Do Not Know, 1937]. But it was her Atmosfaerisk landskab [Atmospheric Landscape, 1936] that Breton chose to reproduce in his Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme [Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism] published on the occasion of the event. The picture bore similarities to Magritte’s figurative Surrealism, and saw E. Thoresen play on the incongruous depiction of a familiar object – a glass jar filled with liquid and held by a hand whose extreme side seems to be fading away into a mental landscape. During her brief stay in Paris, E. Thoresen met Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, Yves Tanguy, and also most likely Kay Sage (another forgotten woman of the surrealist movement), Max Ernst, Jean Arp, and Sophie Taeuber, with whom she became friends, and who reproduced her Abstrakt komposition [Abstract Composition] in the magazine Plastique, which she had just started.3 Through contact with the Parisian surrealists, especially Yves Tanguy, E. Thoresen’s work became more and more oneiric, an array of imaginary worlds drawn solely from her subconscious. The artist continued working after World War II, and was the only woman from the Danish group to take part in the International Surrealist Exhibition organised by A. Breton in 1947 at the Maeght Gallery.

And so it was in Paris that these three Scandinavian artists, in spite of the misogynistic discourse of the male leaders of the Parisian movement, confirmed their affiliation to the surrealist movement and succeeded in affirming their independence of mind and creating their own language, both poetic and subtle. While their works are in many ways assertive of their feminine identities and tell of an experience that was very unlike that of men, they remain no less powerful and profound as those produced by their male counterparts.

“Appel à la lutte”, 10 February 1934, Tracts surréalistes et déclarations collectives, edited and annotated by José Pierre, vol. I (1922-1939), vol. II (1940-1969), Paris, Losfeld, 1980 and 1982, vol. I, pp. 262-3.

2

Entries 188 to 195 of the catalogue: Dialogue, La Fête [The Party], Danse et Contre-danse [Dance and Counter-Dance], Le Rêve [The Dream], Fantôme sur la plage [The Phantom Beach], Nature morte [Still Life], Automne [Autumn], Arbre blanc [White Tree].

3

Plastique, No. 3, 1938, p. 11.

Nathalie Ernoult, "Three Scandinavian surrealist women artists in Paris." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/trois-artistes-femmes-surrealistes-scandinaves-a-paris/. Accessed 12 July 2025