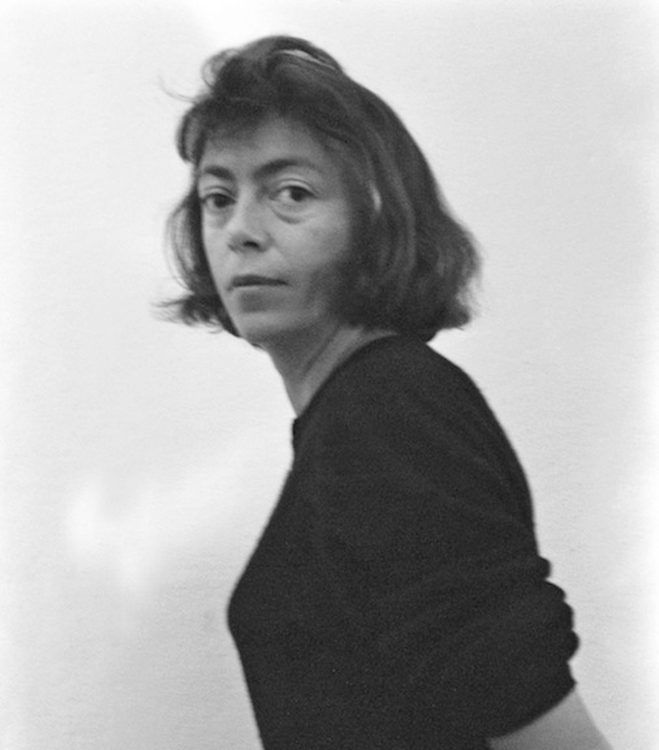

Helen Phillips

Cohen David, « Helen Phillips », The Independent, London, February 17th, 1995.

American sculptor and printmaker.

Moving on rapidly from her classical training and lured by the prospect of hands-on experience, Helen Phillips studied sculpture at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco, where she got to know Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and whose collection of pre-Columbian statuettes she greatly admired.

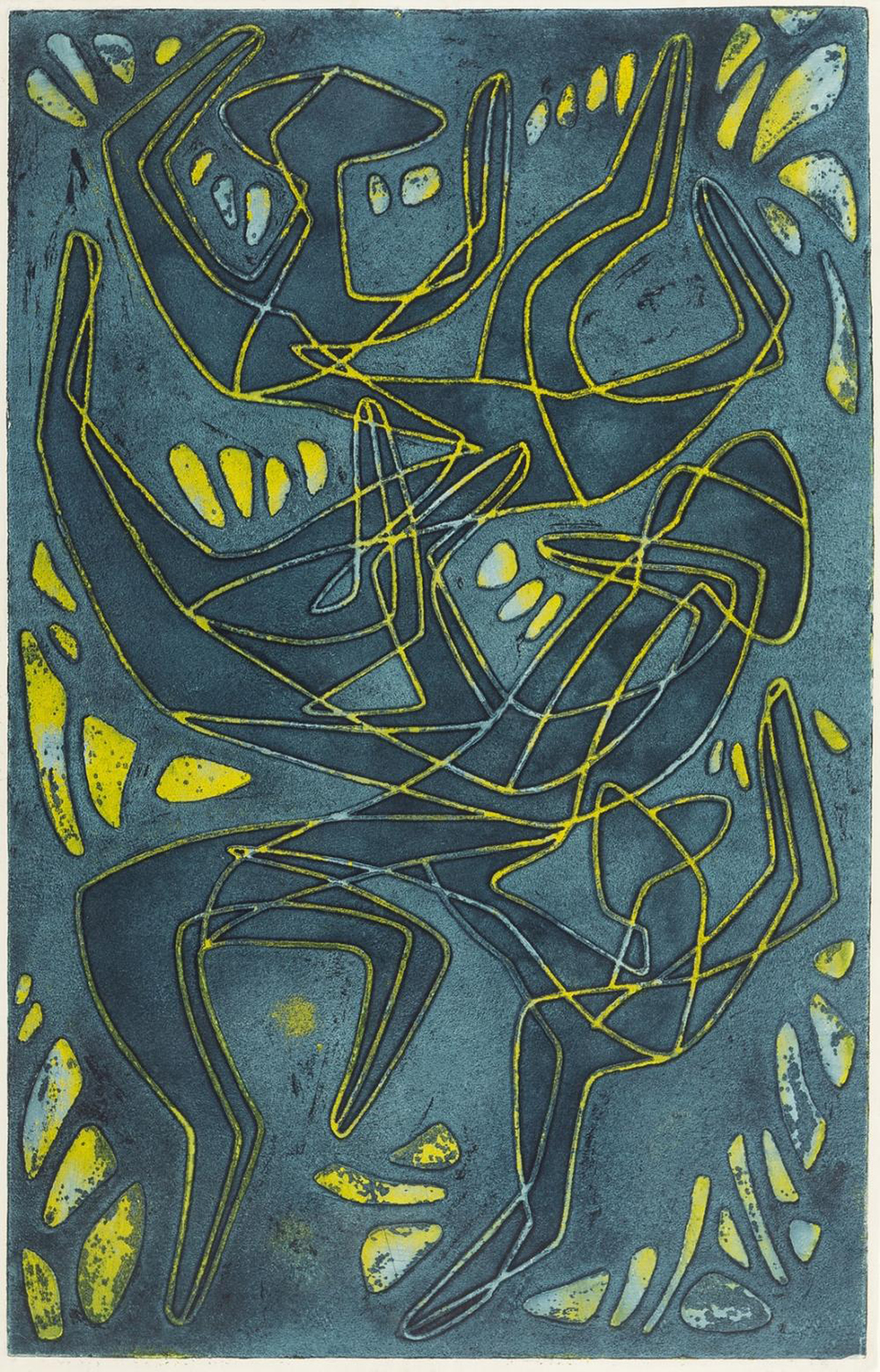

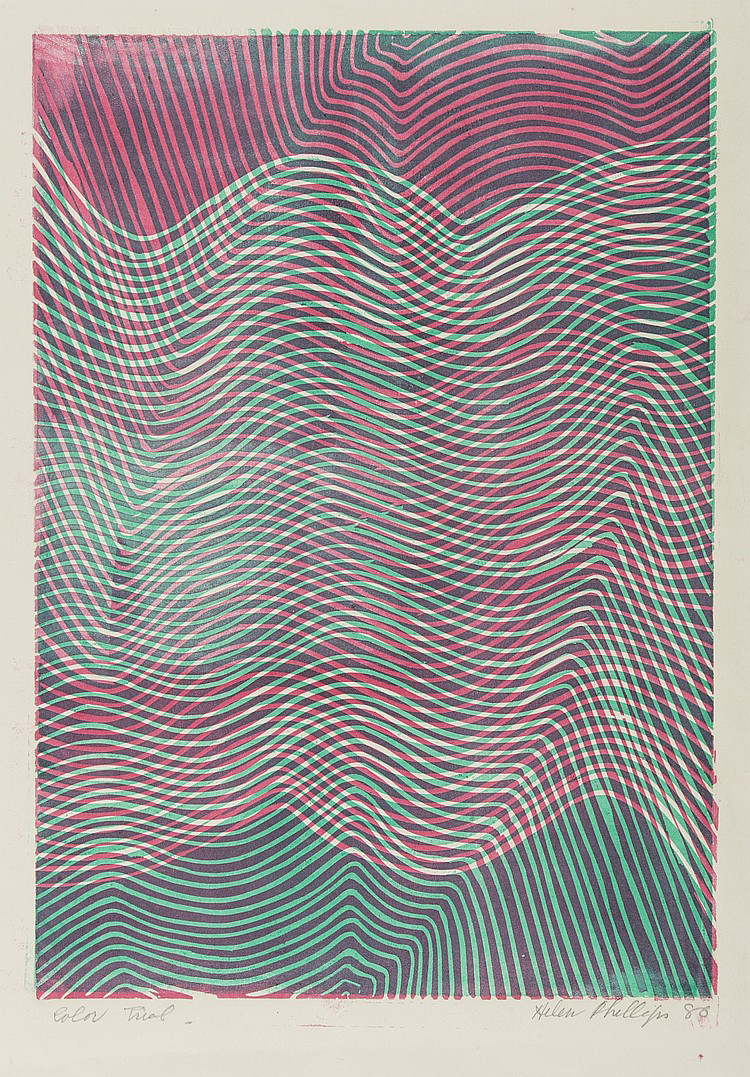

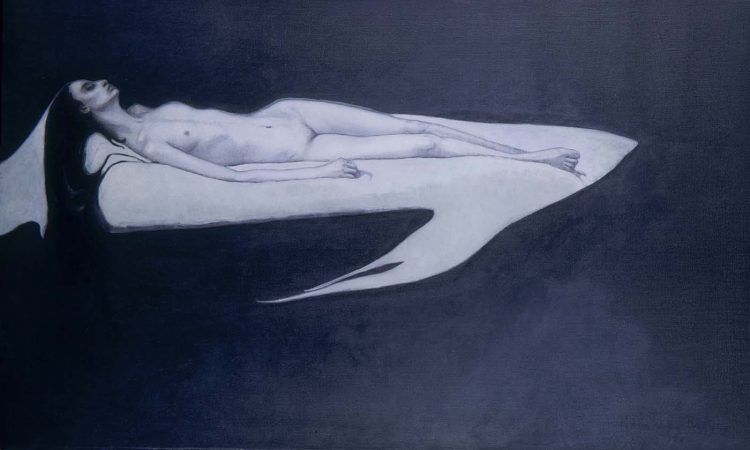

The commissions, grants and awards she received from an early stage enabled her to travel to Italy and France. In 1936 she was admitted to Atelier 17 (1927-1988), the hub of experimental printmaking in Paris and a mecca for a vast number of avant-garde artists spanning a wide spectrum of countries, generations and styles. The studio was founded and run by painter-printmaker Stanley William Hayter (1901-1988), who became her husband and the father of her two children. The Atelier’s cosmopolitan whirlwind raised H. Phillips’ awareness of the inextricable ties that existed between printmaking and sculpture and led her to produce around thirty Surrealist-inspired plates using by automatic writing. Printmaking fine-tuned her perception of space and the ensuing transformation of her relationship to sculpture, her predominant artistic expression.

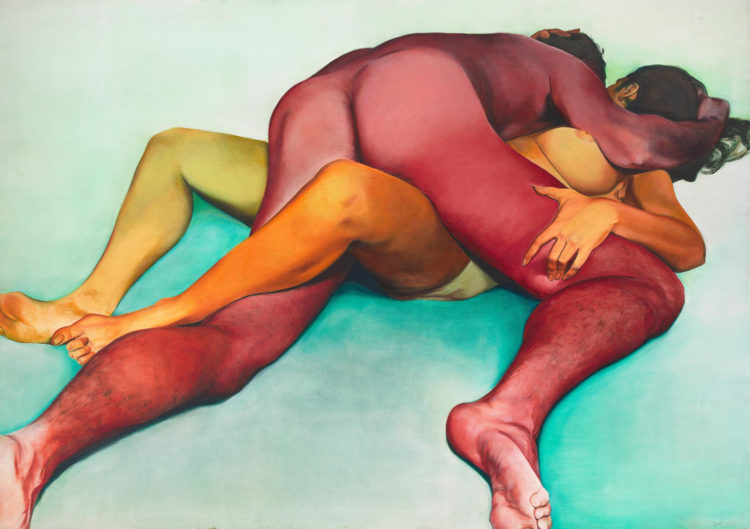

At the end of 1940, because of the war, the couple set up home in New York. S. W. Hayter relaunched Atelier 17, attracting a host of printmaking enthusiasts including William Baziotes (1912-1963), Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), Robert Motherwell (1915-1991), Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) and Marc Rothko (1903-1970) and joining forces with the exiled Surrealist artist community and the young generation of American Abstract Expressionists. In New York, H. Phillips took part in several exhibitions, including 31 Women (1943) at Peggy Guggenheim’s The Art of This Century gallery and Blood Flames at the Hugo Gallery (1947), where her bronzes were highlighted in an exhibition designed by Frederick Kiesler.

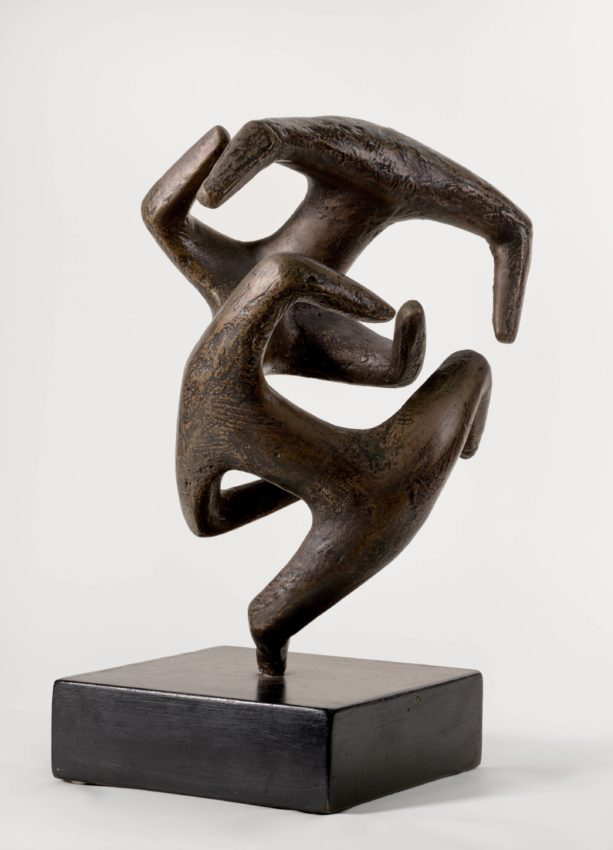

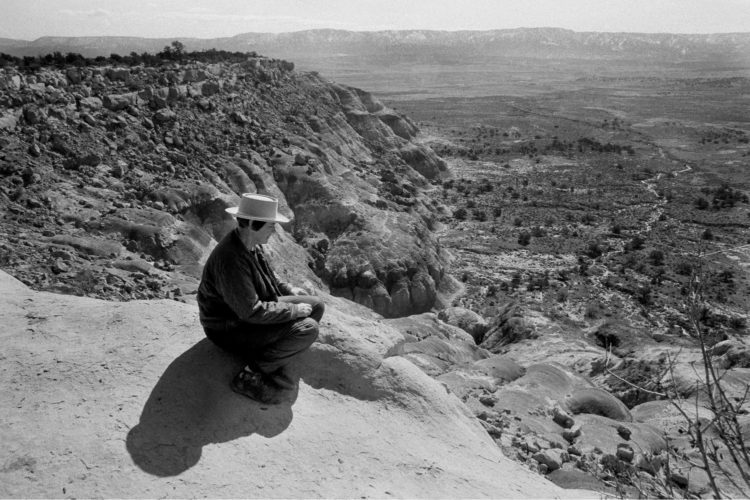

In 1950, despite a successful career ranking her among America’s women pioneers in the field of Abstract Expressionist sculpture, H. Phillips decided to return to Paris with her husband. From then on she exhibited her works at international artistic events. Métamorphose II (1951-1952) won the French entry in the International Sculpture Prize, launched in London in 1952 in order to create a monument to an unknown political prisoner. At this point she began working with balsa wood and old oak to produce giant totems. While Lyrical Abstraction was reaching its apotheosis in Paris, H. Phillips was sculpting modular, multiple, expanding forms using her favourite materials, bronze (Jeux de la gaîté, 1953), copper (Amants novices, 1954) and wood (Adam et Ève de l’Ardèche, 1956-1958). This period also coincided with her contribution to the exhibition This is Tomorrow (1956) at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, a suspended balsa wood sculpture titled Jeux de jambes (1968). With an unfailing determination to depict movement in space, she also created expanding geometric structures, some of them mobile, such as Growth (1961), described and reproduced in 2021 in the exhibition catalogue United States of Abstraction. Artistes américains en France 1946-1964, shown at the Musée d’Arts in Nantes and later at the Musée Fabre in Montpellier.

A serious accident occurred in 1967, however, while she was manipulating her Alabaster Column (1966), which had just been purchased by the Albright Knox Museum in Buffalo, and this put an end to her monumental projects. She went on to produce a range of small-scale, light wire structures in a more delicate and intimate vein.

H. Phillips’ works are held in a large number of American museums, as well as in private collections both in Europe and in the United States. On her death, the British daily newspaper The Independent paid tribute to her work in a lengthy obituary.