Hilla Becher

Lange Susanne, Bernd & Hilla Becher: Life and Work, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2006

→Maraniello Gianfranco (ed.), Bernd & Hilla Becher at Museo Morandi, exh. cat., Modern Art Museum, Bologna (24 January–19 April 2009), Munich, Schirmer / Mosel, 2009

→Moritz Neumüller, Bernd & Hilla Becher Speak with Moritz Neumüller, Madrid, La Fabrica / Fundacion Telefonica, 2005

Bernd and Hilla Becher: Landscape/Typology, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 21 May–25 August 2008

→Bernd and Hilla Becher, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1974

→Bernd and Hilla Becher: Basic Forms, Getty Center, Los Angeles, 6 May–14 September 2008

German photographer.

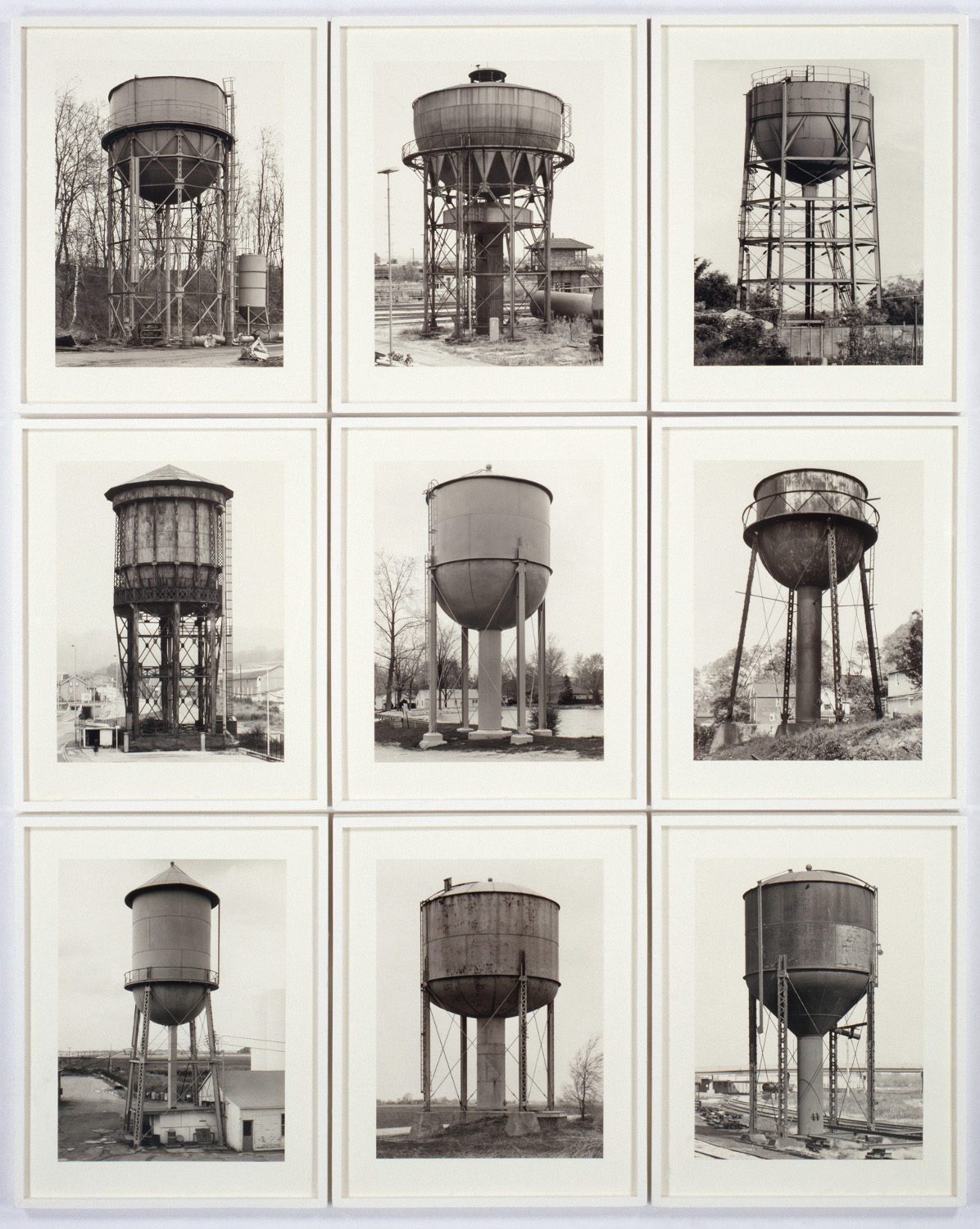

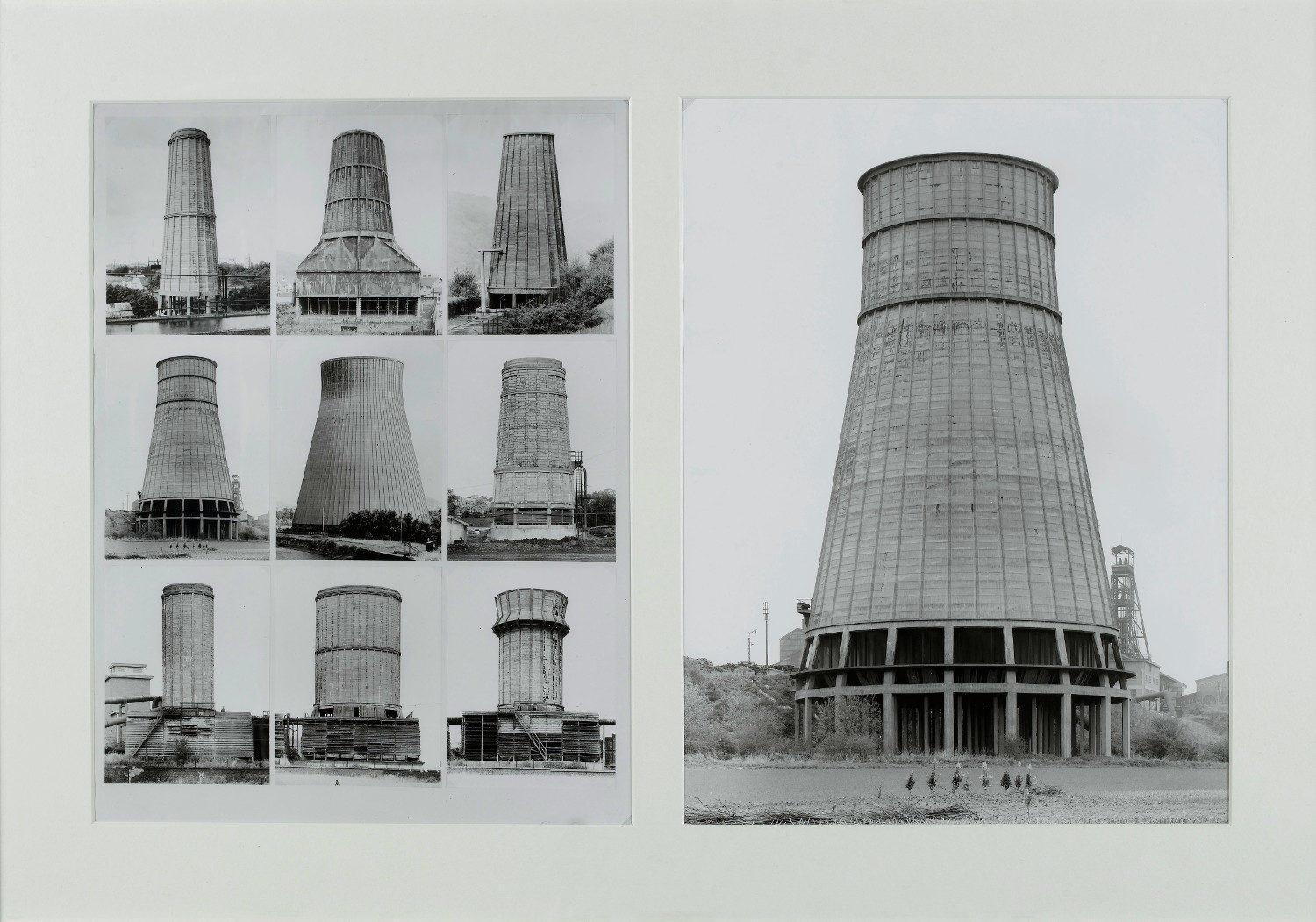

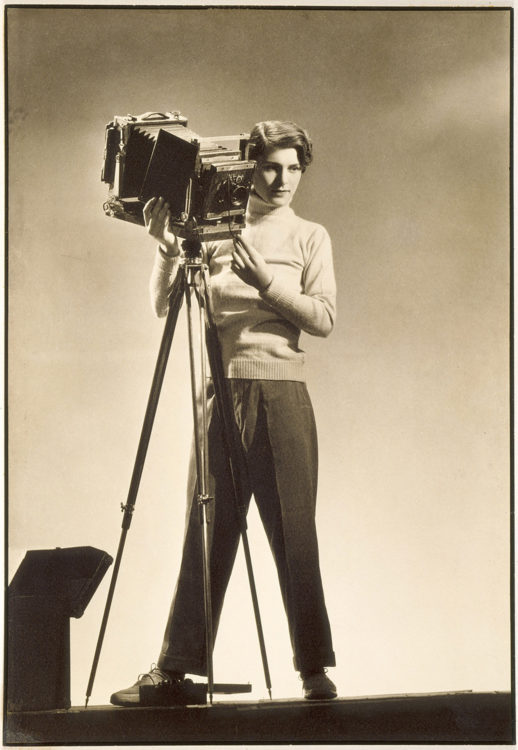

In the history of contemporary photography, the name Hilla Becher is inseparable from that of her travelling companion, Bernd Becher (1931–2007). For fifty years, they shared their lives, but also created a shared body of work. After photography training in Potsdam, she left the GDR to move to Dusseldorf, in 1954. She studied painting at the Staatliche Kunstakademie, before being named director of the photography laboratory. It was there that she met, in 1957, Becher, a former student in painting and typography. From 1959 onwards, they began their artistic collaboration, and were married in 1961. From then on they signed their production under their shared surname, Bernd and Hilla Becher, or, more often, just “Becher”. Their work began with a series of photographs of mines and workers’ houses in the industrial zone of Siegen. From the first shots, a protocol was established that was to remain virtually immutable: with the aid of a view camera on a tripod, they produced black-and-white images in which the photographic subject – a structure or building – was placed in the centre of the image and isolated from its environment. The point of view, slightly elevated, enabled all of the distortion of the image to be avoided, while a long exposure time allowed for greater depth of field. The absence of any human activity in these images contributes to the characterisation of this style, known as “objective”. Countering the subjective photography that dominated the post-war period, the couple’s realist and documentary work has thus been compared to the photography of New Objectivity in the 1920s, that of Albert Renger-Patzch or August Sander. Engineers and theorists of architecture were the first to look into these photographic series, presented in the form of orthogonal grids of 9, 12, or 15 images and inventoried more through a typological than a chronological or geographic principle. Their production has often been described as “industrial archaeology” and interpreted as heritage work, full of nostalgia. Yet this purely socio-historical interpretation has been refuted by the photographers themselves, who retort that “machines, for instance, present no visual interest for [them].”

Beyond the photographic act, the classifying of images is often undertaken according to more structural and aesthetic than historical or geographic criteria: their constant reworking and enhancing of its presentation, from one publication and exhibition to the next, have made their photography a true work in progress. The interpretation of these photographs as that of a repertoire of pure forms, extracted from their context, led minimalist American conceptual artists such as Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt to showcase the work of the Bechers in the 1970s. In 1969, their exhibition, entitled Anonymous Sculptures, was simultaneously organised with a retrospective on American minimalist art. This recognition from the art world was crowned by their participation in Documenta 6 in Kassel in 1977 and, in 1990, by their obtention at the Venice Biennale of a prize for… sculpture. In 2004, when they were awarded the Hasselblad Prize – the highest honour of the photography world – the duality that is intrinsic to their work was, once again, highlighted: the systematic photography of functionalist architecture, with images often organised in grids, led to their recognition from both conceptual artists and photographers alike. The Bechers left the door open to all interpretations: artistic, patrimonial, or documentary. This was one way of proving, as Jean-François Chevrier affirms in his book, Entre les beaux-arts et les médias (2010), that the photographic subject does not have to choose between “artwork or document”. This acknowledgement of ambivalence constituted their principal contribution to a new generation of photographers known as “realists”, newly created by the professor of “artistic photography” at the Staatliche Kunstakademie. It is possible to speak of a Düsseldorf School or Becher School, given the powerful impact that they have had on this new generation. Their work has frequently been exhibited, all over the world.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Becher Photography Exhibition in the Ruhr Valley

Becher Photography Exhibition in the Ruhr Valley