Huguette Caland

Huguette Caland, mes jeunes années, exh. cat., Galerie Janine Rubeiz, Beirut (12 January – 12 February 2011), Beirut, Galerie Janine Rubeiz, 2011

→Huguette Caland, Everything Takes the Shape of Person, 1970-78, Genève, Skira, 2018

→Huguette Caland : works, 1964-2012, Beirut Exhibition Center (2012), Beirut, Solidere, 2013

→Anne Barlow (ed.), Huguette Caland, exh. cat., Tate St Ives (2019), London, Tate Publishing, 2019

Huguette Caland, Beirut Exhibition Center, Beirut, 14 January – 28 February 2013

→Huguette Caland, Tate St Ives, St Ives, 24 May – 1 September 2019

→Huguette Caland. Tête-à-Tête, The Drawing Center, New York, 22 May – 13 September 2020

Visual artist.

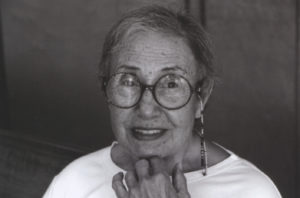

Huguette Caland, who at the time of writing, has only recently passed at the age of 88 from complications with a neurological condition – was an ebullient figure who did not seek convention or the life that was set out for her; she could have lived an uncomplicated, lavish, and perhaps, even beautiful life. Instead, H. Caland opted for freedom – this is no hackneyed use of the term, when one considers the context of Caland’s upbringing and the subsequent decisions she chose to make in her life.

In 1943 when H. Caland was 12, her father became the first post-independence president of Lebanon. As his only daughter, the expectations were that she would be a matronly wife to a Lebanese man. Yet, she chose a tenacious lifestyle. She married a Frenchman, Paul Caland, who was the nephew of one of her father’s rivals, had children, and took lovers.

She attended art school later in life in her 30s at the American University of Beirut and for a time was part of a scene associated with her friend Helen Khal (1923-2009) who opened Gallery One in Beirut, which as well as showing H. Caland, presented the art of Etel Adnan (1925-2021), Simone Fattal (born in 1942), Shafic Abboud (1926-2004), among many others who would come to be known as leading Lebanese modernists.

Yet, for whatever reason, those carefully grafted contours did not find their place in Lebanon and H. Caland left her husband, children and lover and headed for Paris in 1970. Here, an entirely new milieu opened up for the artist. She began her infamous Bribes de Corps series (which she produced all throughout the seventies). These works, which are evidently self-portraits of a form –represent voluptuous, contorted, colourful shapes and abstractions, which invoke the body but never reveal them.

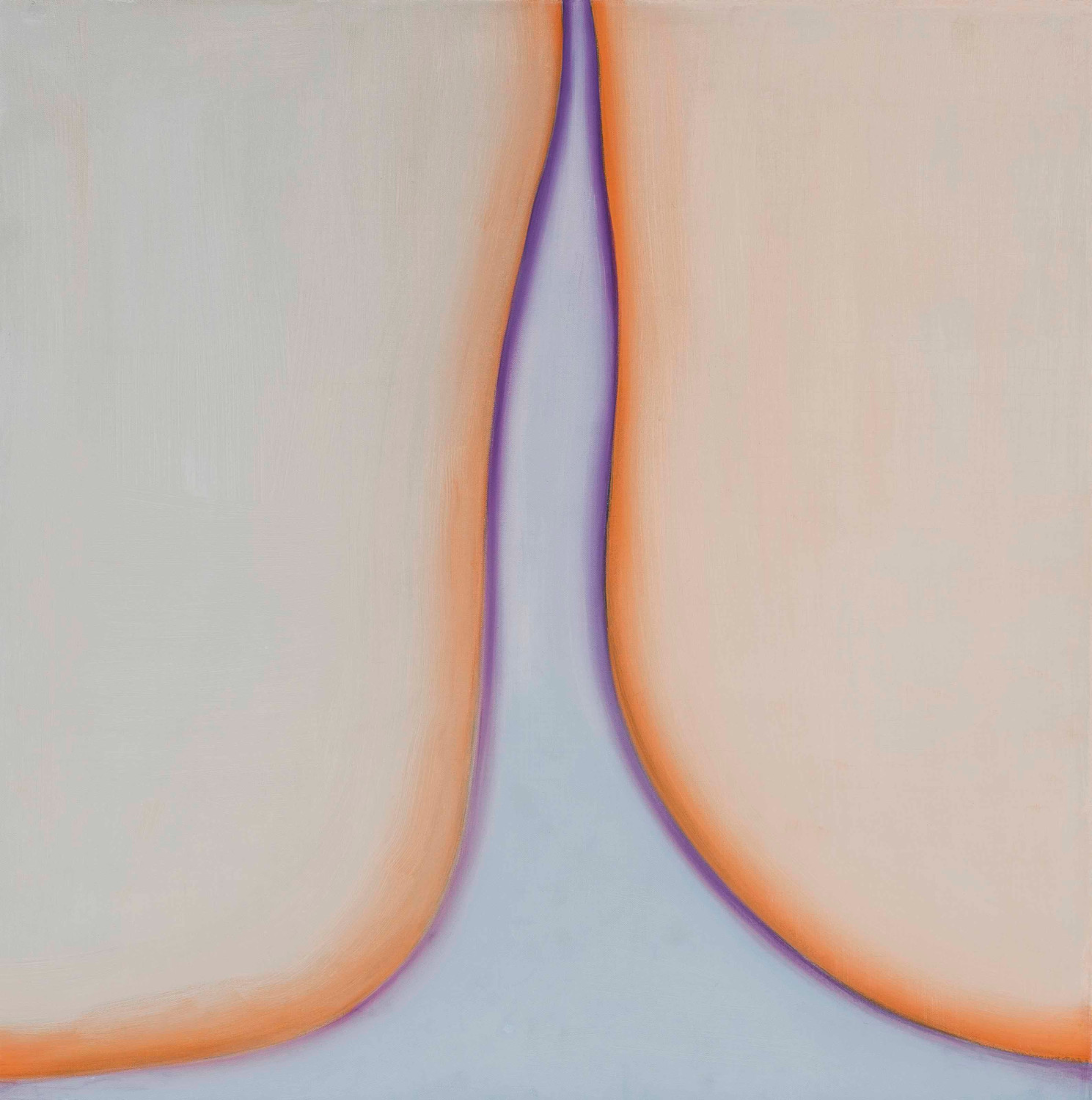

These works, among many others boast a pointed, but subtle eroticism. Take for example, Bribes de corps (1973). A malformed shape that could be two lips sit before you –descending into shadow. Are they here to seduce you? Or simply to be admired? In Bribes de corps (1979) – a central shape that might well be a body, or uterus, or any other interior female body part explodes with reliefs of pink and orange and yellow. In one of her most playful provocations, Bribes de corps, self-portrait (1973) we see a beautiful pink canvas before us. One could think this a formal kind of colour field painting, only you look at the bottom of the painting and realise a little crack: a female buttock protruding before you.

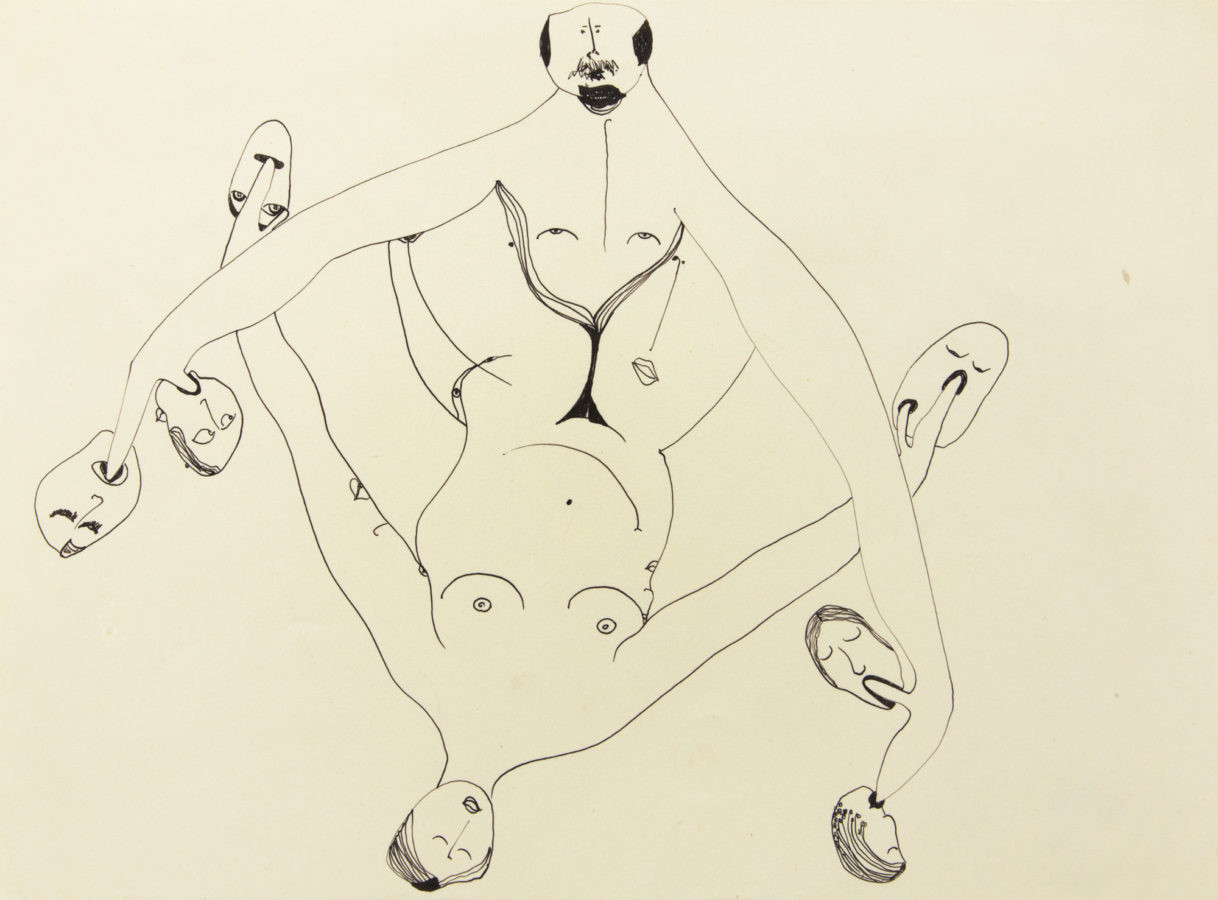

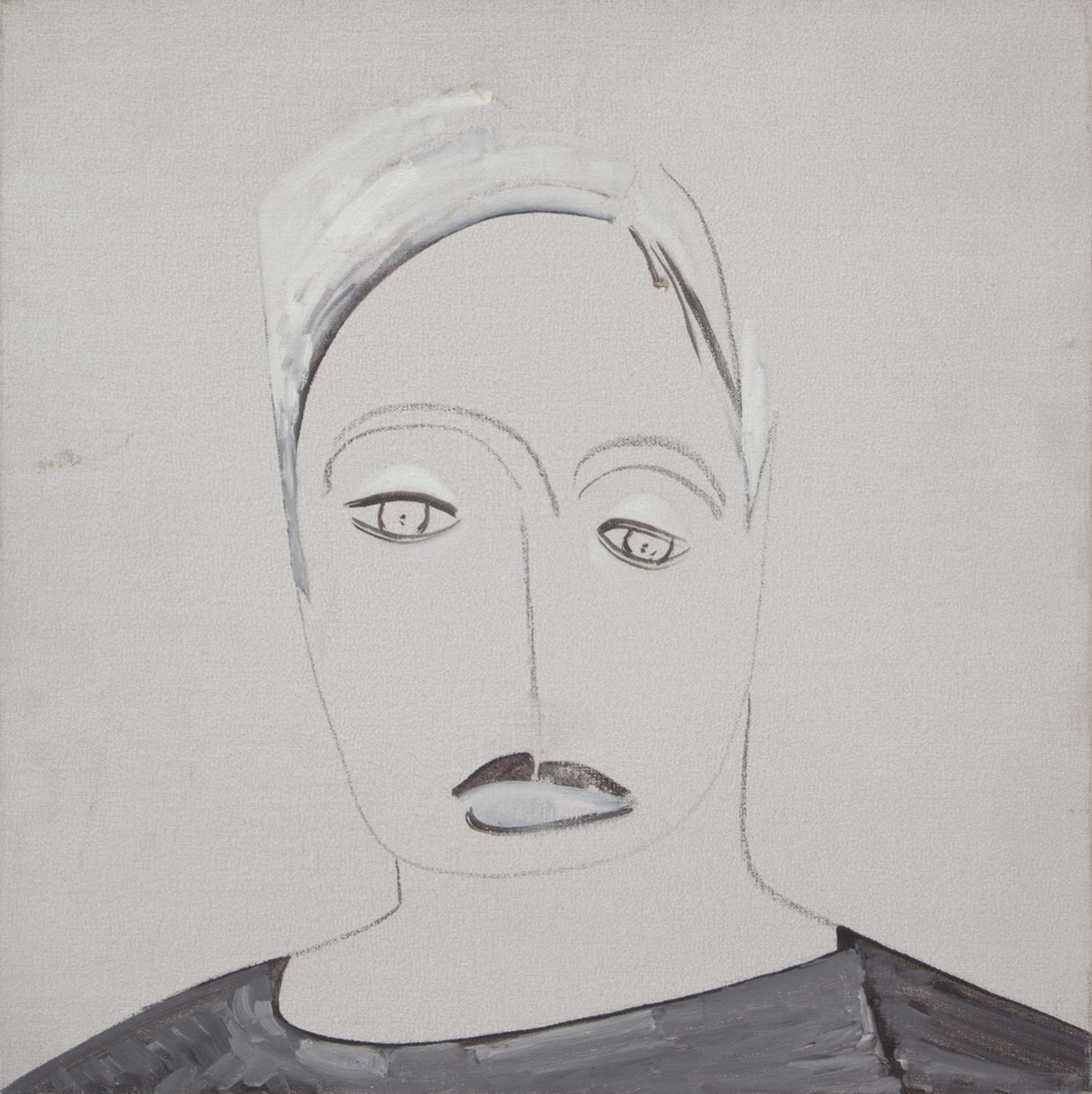

A lot has been said of the precision of H. Caland’s ‘line’, which I cannot forget here. Beyond her paintings, the artist produced a prolific amount of complex drawings to the end of her life, which often featured her lovers such as one of her regular muses, Mustapha, who appears in the faultlessly executed, Moustapha, poids et haltères (1970). This all-consuming focus carried on throughout her career including in her dresses and smocks that she produced in collaboration and for Pierre Cardin in Paris. The dresses, I believe, may have been inspired by the large kaftans she made for herself while living in Beirut, when at the time H. Caland was still considered by societal standards to be overweight.

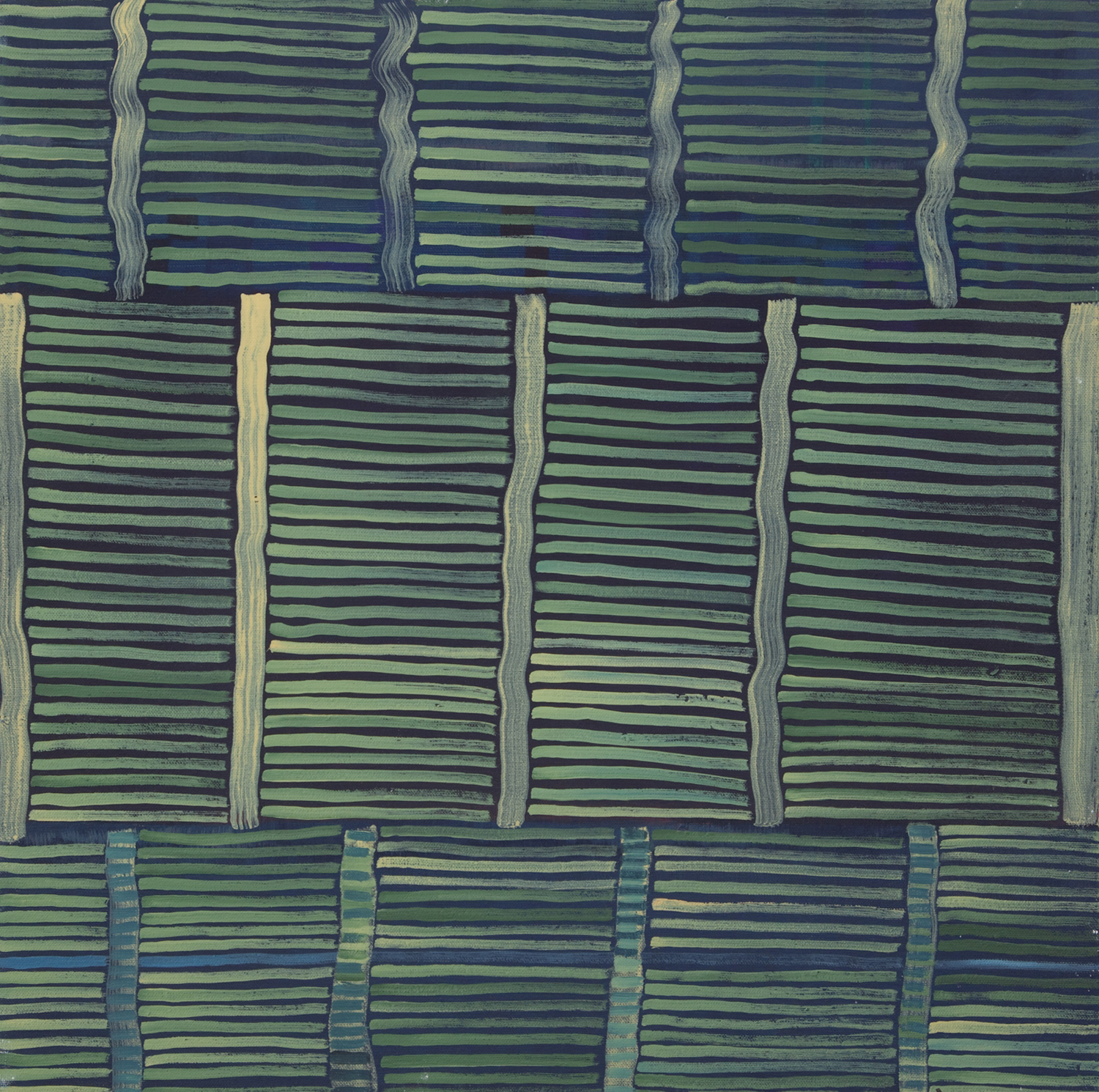

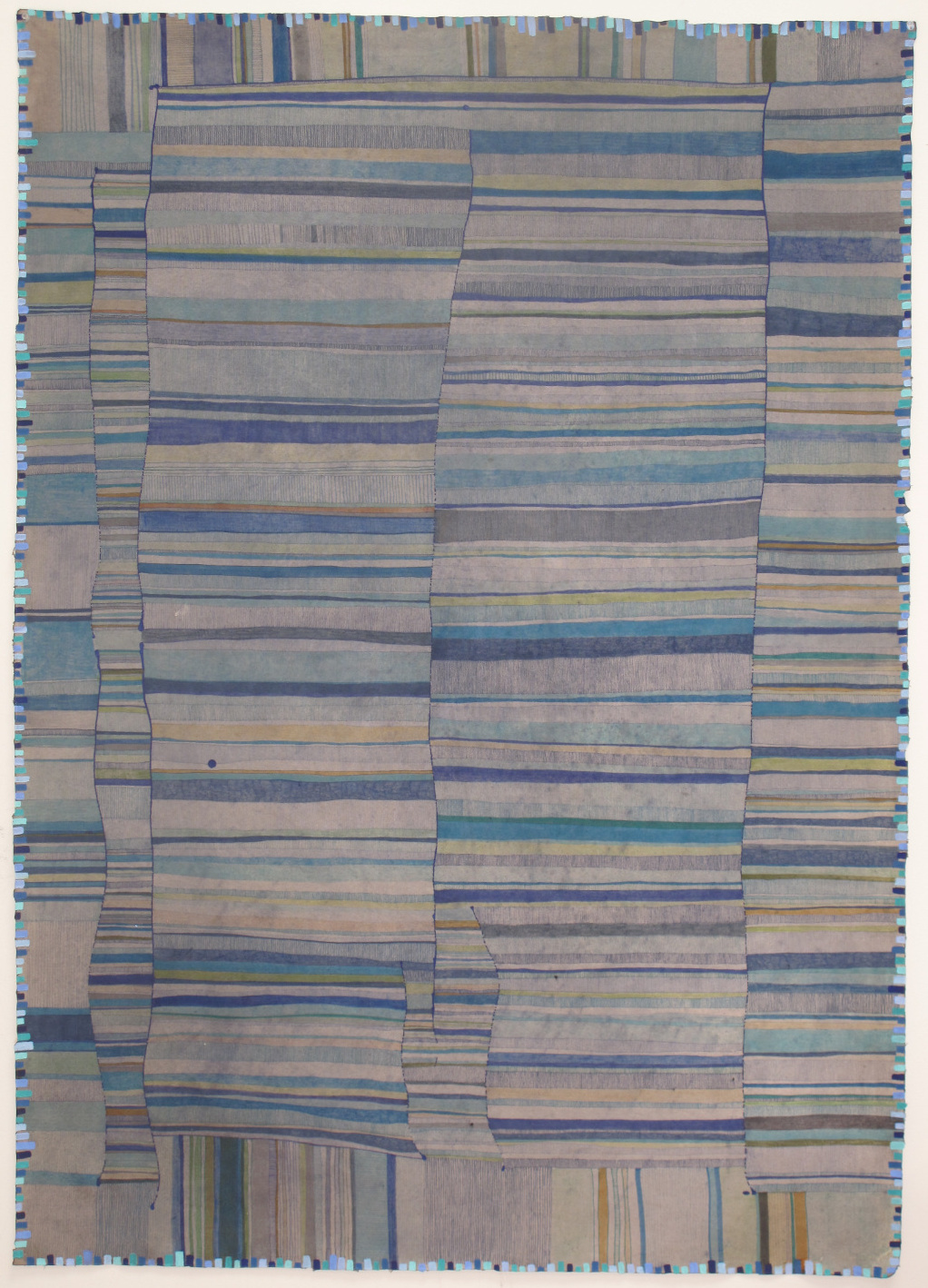

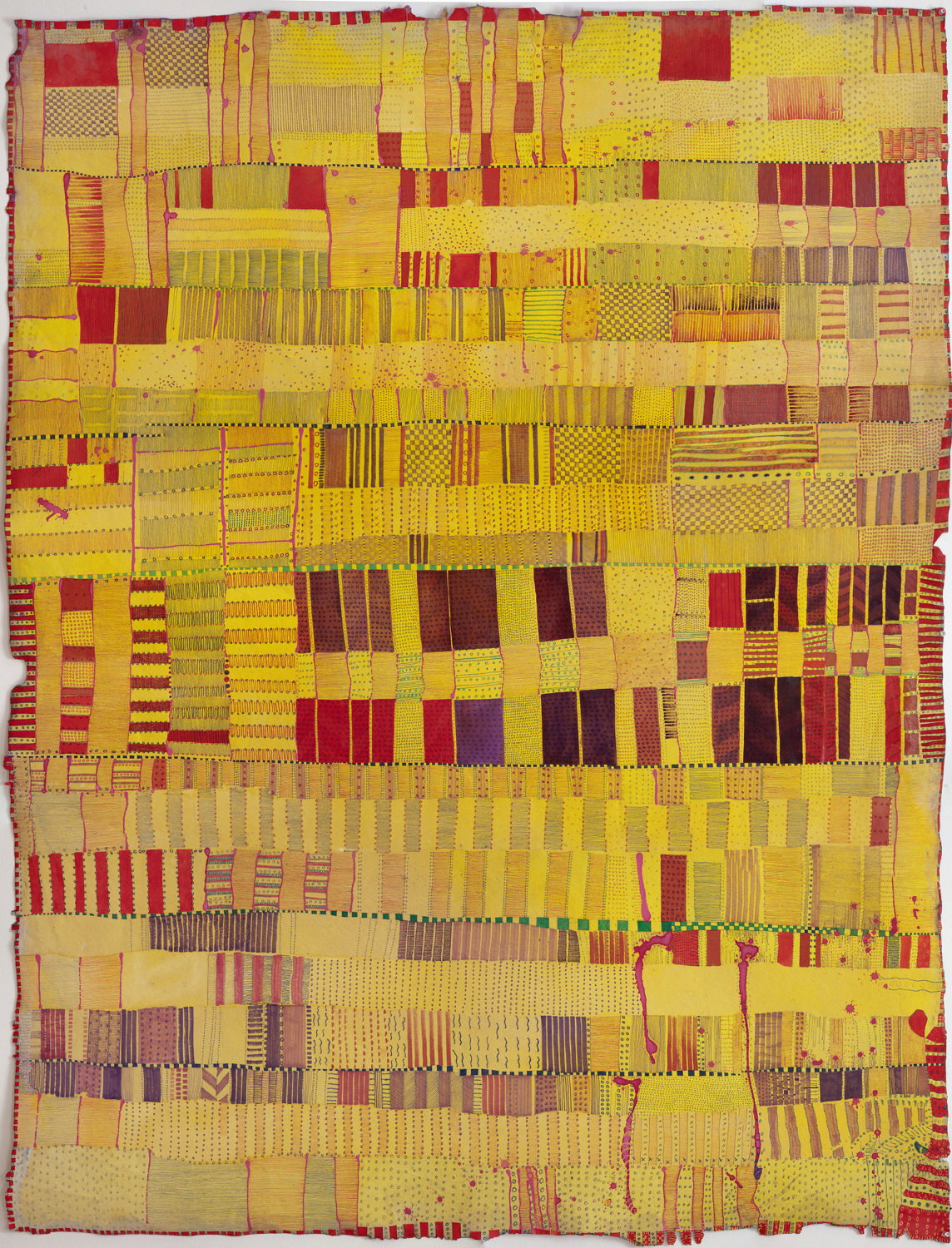

In 1987, H. Caland was in a relationship with sculptor George Apostu (1934-1986), and when he passed away, she decided to move her life to Venice, California. Here, she set up a beautiful home and studio, which in itself became an artwork. The bar handles in the bedroom cupboards entered into painted mouths and the kitchen was overtaken by a giant mural. It was here that it was believed that Caland became a doyenne of the Los Angeles art scene, appropriately the centre of a circle of artist friends, the closest of whom was the late Ed Moses (1926-2018). Here, she would often spend days in the studio working on large scale tapestries with marker and pen among other materials. An example of work from this period is Under Cover VI (Date unknown), where we see H. Caland’s signature eroticized body but amidst a landscape of ever more colourful multiplicitous forms. In later life, she produced the Rossinate diptych (2011), one of her final works. Here, body and space explode into a universe that looks like it emerged from a utopian future.

Due to ill health, H. Caland returned to Beirut in 2013, where she ultimately passed away in 2019. Six months before her return a major survey was staged at the Beirut Exhibition Center. Exhibition interest has been growing since. This has included a major presentation in the Made in L.A. biennial at the Hammer Museum in 2016, a precise survey at the 14th Sharjah Biennial in 2019, a solo show that covered fifteen years of her career at Tate St Ives, also, in 2019, and a solo exhibition, her first ever in an institution in the United States, at the Drawing Center in 2020.

Despite this newfound attentiveness, one can consider it minor and severely delayed considering the vast output that H. Caland produced over her prodigious life. For the Arab world, Huguette is one thing -the woman who was brave enough to break with conformity to forge a path that enabled her to arguably be the Arab world’s first erotic abstract artist. Yet, her work should never be relegated to the Arab world, Caland was as much French as she was American, and her field of inspiration and in turn influence, should reflect and speak back to a global art history -a history that has for too long left her work at the margins.

Lettre à Huguette by Fouad Elkoury, 2021

Lettre à Huguette by Fouad Elkoury, 2021  Huguette Caland - Interview

Huguette Caland - Interview