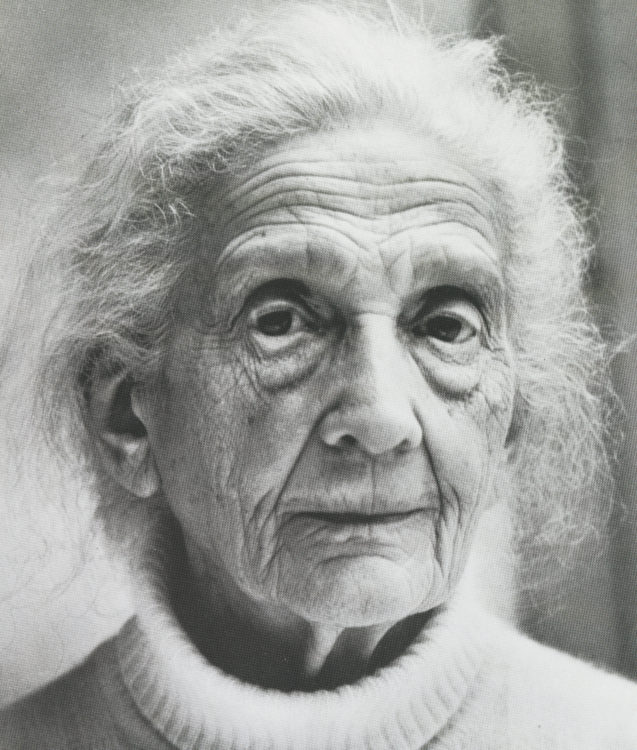

Isabel Steva Hernández (dite Colita)

Capmany, Maria Aurèlia and Steva, Isabel, Antifémina, Madrid, Editorial Nacional, 1977

→Rosón, María, “Colita en contexto. Fotografía y feminismo durante la transición española”, Arte y políticas de la identidad, n. 16, Murcia, 2017, pp. 55-74

→Terré, Laura, Colita: ¡Yo no soy un espejo!, Madrid, La Fábrica, 2010

La Gauche qui rit, Sala Aixelà, Barcelona, December 3 and 4, 1971

→Retrospectiva, Sala EFTI, Centro Internacional de Fotografía y Cine, Madrid, April 3-May 5, 2009

→Colita, ¡porque sí!, Fundació Catalunya La Pedrera, Barcelona, March 11-July 13, 2014

Catalan photographer.

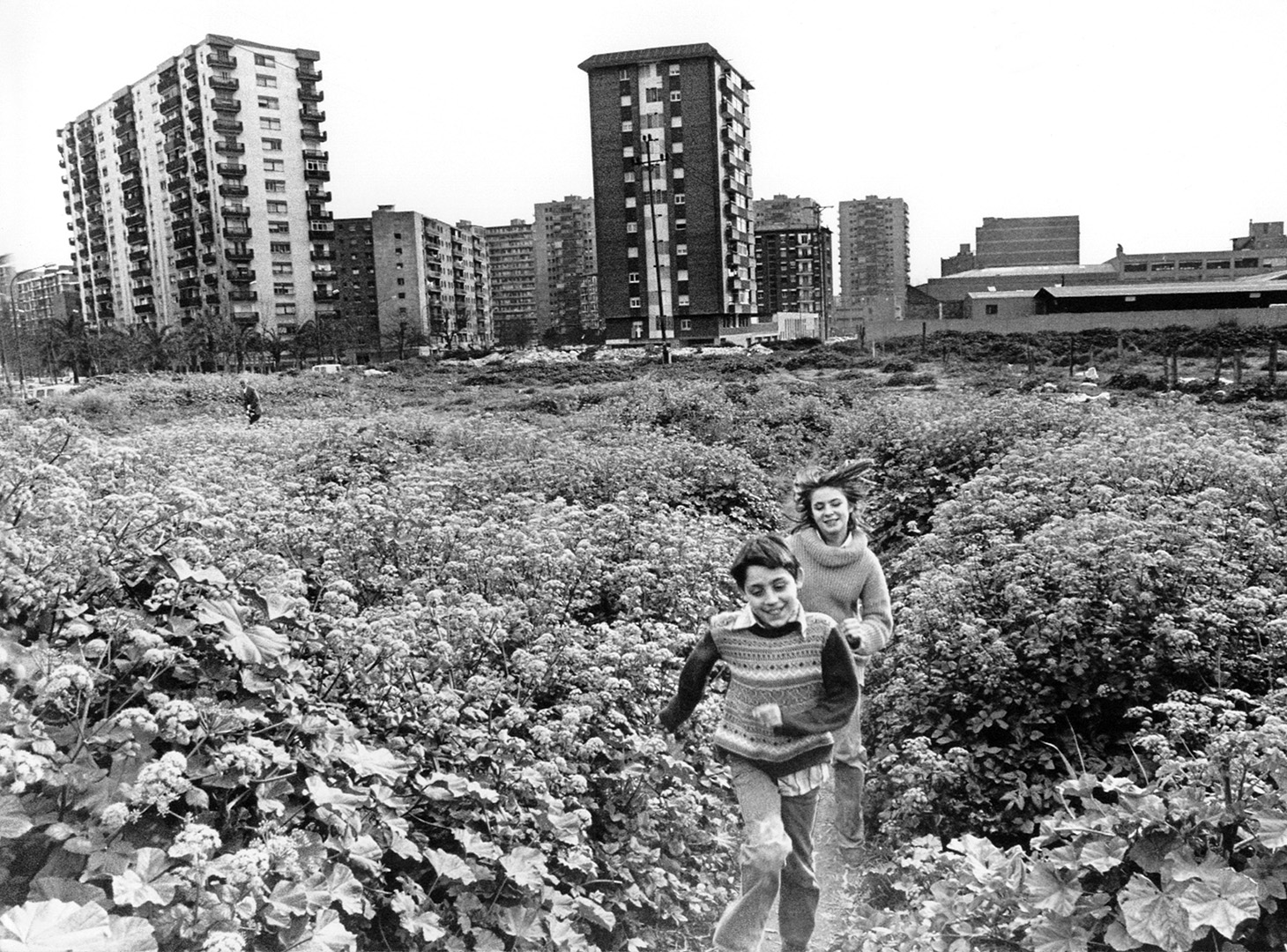

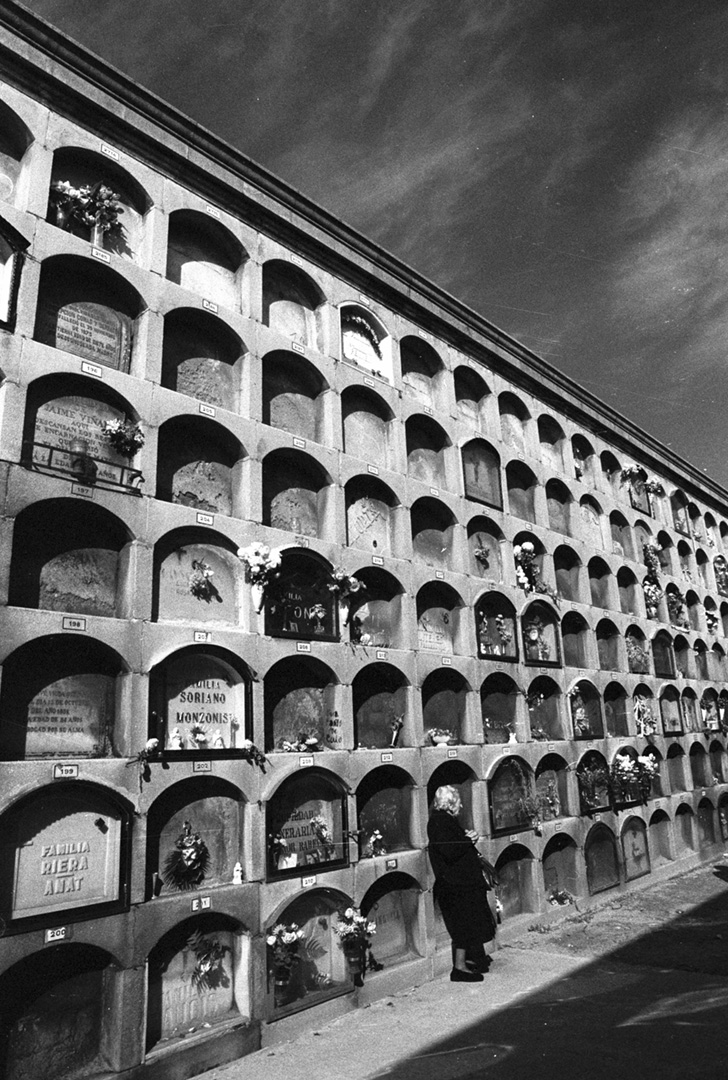

Isabel Steva Hernández, nicknamed “Colita”, is one of Catalonia’s best-known photographers. Among the subjects addressed in her enormous body of work are the world of flamenco, theatre and show business in general, the 1970s feminist movement, and scenes and urban landscapes of her beloved Barcelona.

Colita was born into a middle-class family in the Barcelona neighbourhood of L’Eixample. After her graduation from a Catholic high school, her parents enrolled her in secretarial school, a mandatory rite of passage for women in those days because it supposedly facilitated their entry into a profession and consequently a degree of economic autonomy before marriage. But she totally rejected marriage, and instead moved to Paris in 1957 to study French language and culture at the Sorbonne. The following year, stricken with nostalgia, she returned to Barcelona, where she met the photographers Oriol Maspons (1928-2013), Julio Ubiña (1921-1988), Francesc Català Roca (1922-1998) and Xavier Miserachs (1937-1998). Learning about photography was the first step in her subsequent career as an artist. In 1961 she acquired professional skills in the studio of Xavier Miserachs, who employed her as a secretary and taught her darkroom techniques.

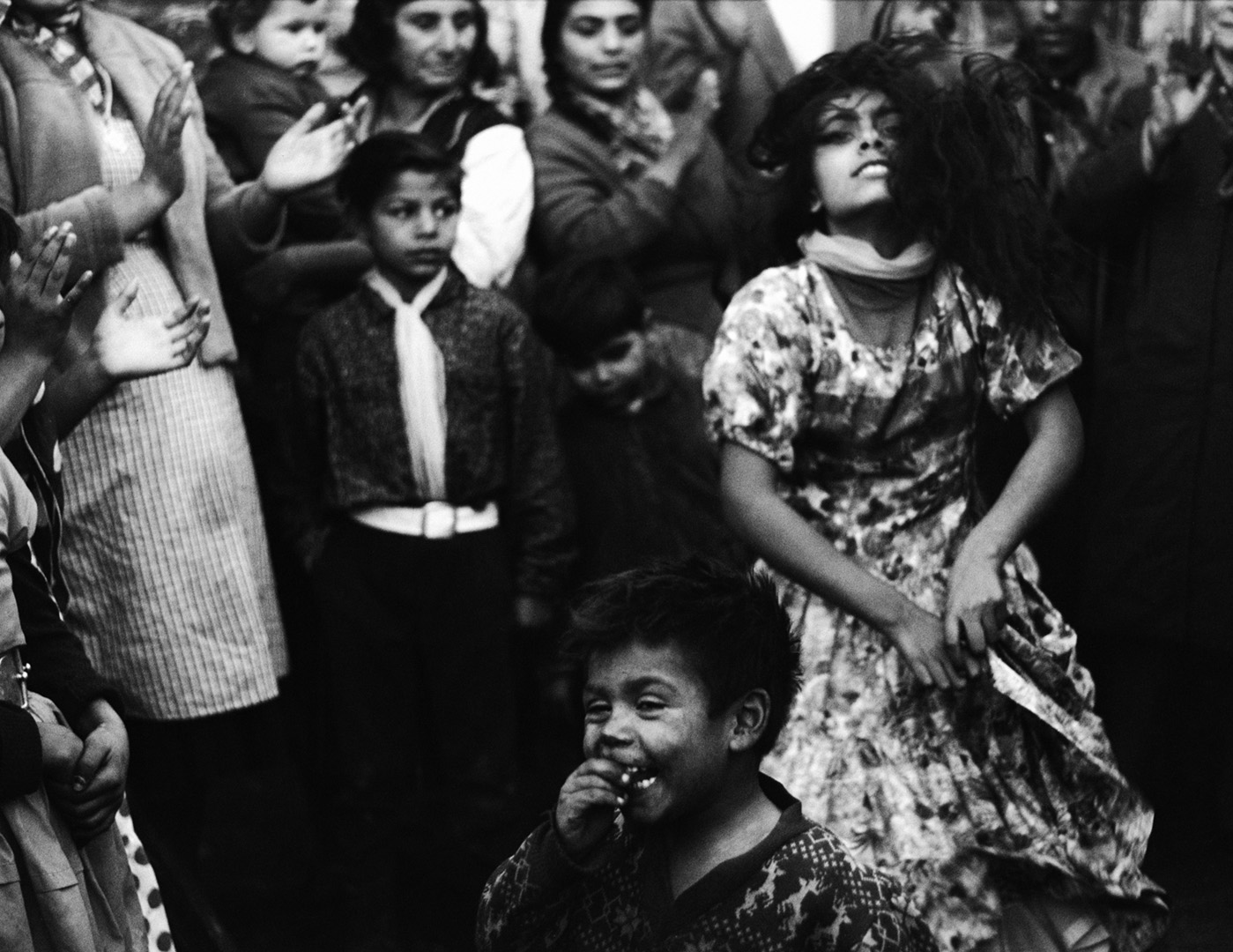

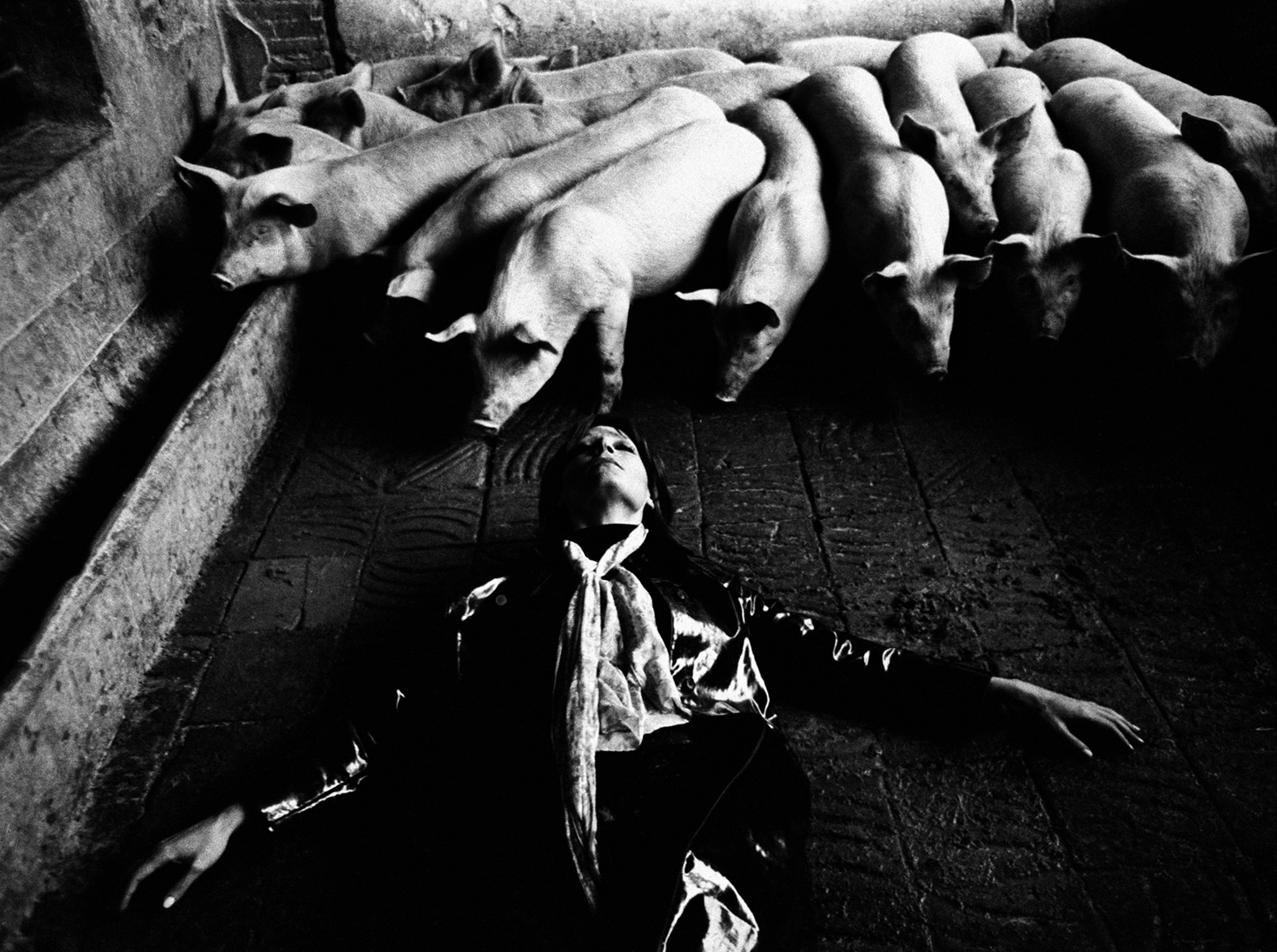

Colita saw photography as a tool to produce memory and community. At the same time, as the art historian Laura Terré has pointed out, she rejected the conception of this medium as a mirror and instead emphasised its expressive powers. She conceived her pictures as a homage to the life and work of her contemporaries, the spaces they inhabited and their worldly activities. In her first exhibition, La Gauche qui rit [The smiling left] (Sala Aixelà, Barcelona, 1971) she presented numerous portraits of her current friends, a group of intellectuals and artists who earned the nickname “Gauche Divine” [Divine left] through their irreverence, exuberance and creativity, in contrast to the orthodoxy of the Spanish Communist Party. She also took disturbing photos of flamenco dancers and their surrounding, some of the most notable appearing in the album Luces y sombras del mundo del flamenco [Light and shadow of the flamenco world, 1975].

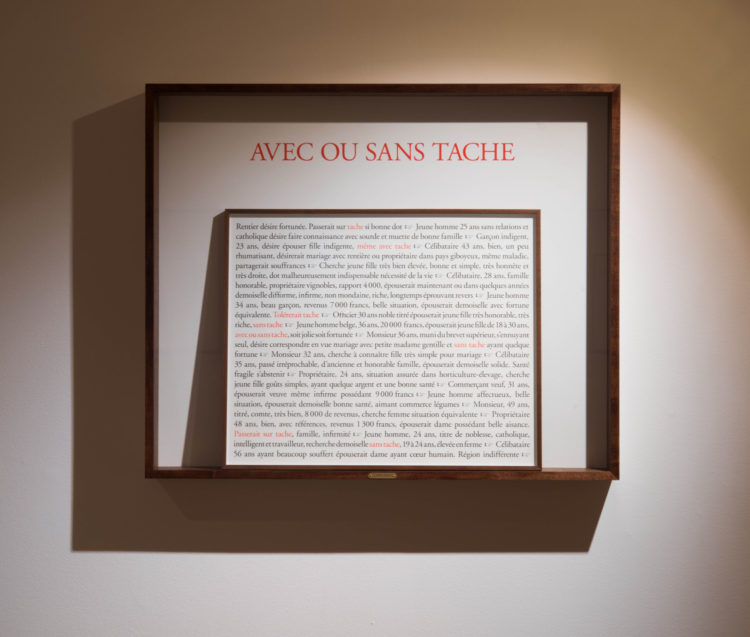

Equally determinate was her partisanship with the feminist movement through her work as a photojournalist and designer for the magazine Vindicación Feminista (1976-1979), a core publication of second wave feminism in Spain, and Antifémina (1977), a photo book with a text by the writer Maria Aurèlia Capmany. This publication sought to “render visible the other side of the typical image of women” and go more deeply into the concept of “antifeminine”, meaning the vast majority of women who do not fit the aesthetic, ethical and moral standards imposed by patriarchy.

In 1998 the Barcelona city government awarded her the Medalla al Mérito Artístico, and in 2004 she received the Cruz de Sant Jordi from the Generalitat de Cataluña. Her work can be seen in museums such as the Museo Nacional de Arte de Cataluña (MNAC), the Fundación Joan Brossa, the Archivo Nacional de Catalunya and the Archivo Municipal de Barcelona.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022