Isabelle Waldberg

René de Solier, Waldberg, Paris, Galerie Éditions du Dragon, 1960

→Robert Lebel, Isabelle Waldberg, à l’entrée ou à la sortie de son palais (secret) de la Mémoire, Paris, Le Point d’être, 1971

→Patrick Waldberg, Isabelle Waldbeg, Un amour acéphale, correspondance, 1940 1949, Paris, La Différence, 1992

Isabelle Waldberg : sculptures, Hôtel de ville de Paris, Paris, 27 September–15 October 1978

→Isabelle Waldberg: Skulpturen 1943-1980, Kunstmuseum, Bern, 27 June–30 August 1981

→Mémoire(s), sculptures, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Chartres, 16 October 1999–3 January 2000

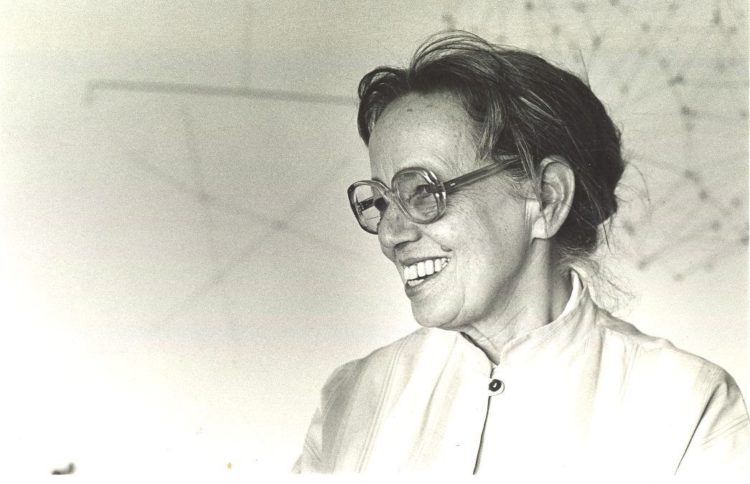

Swiss sculptress.

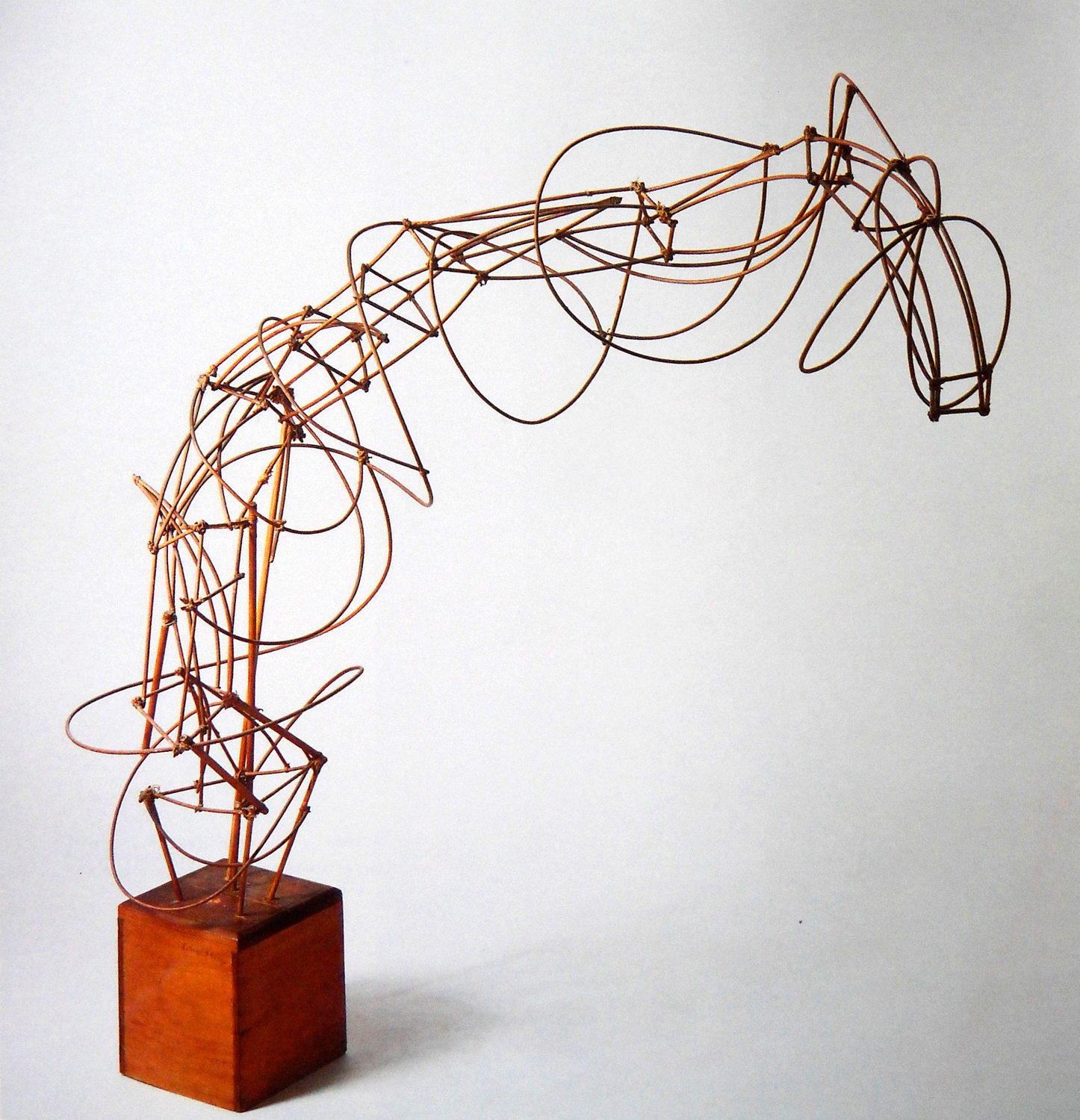

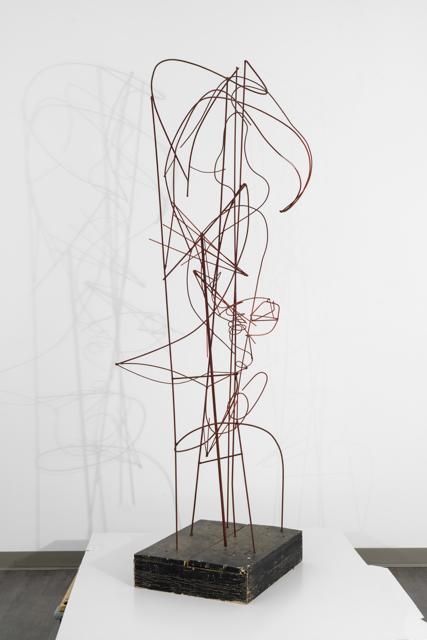

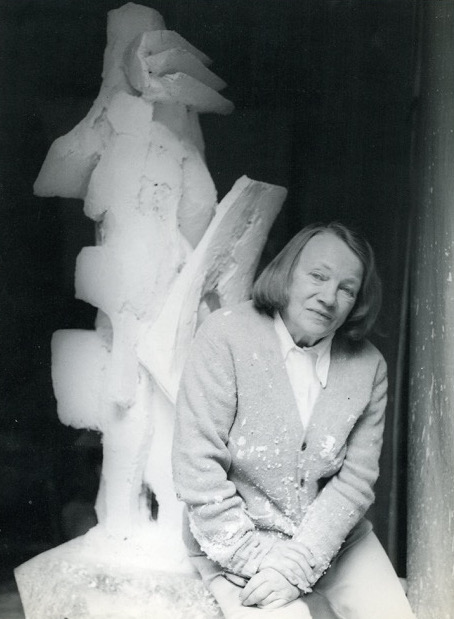

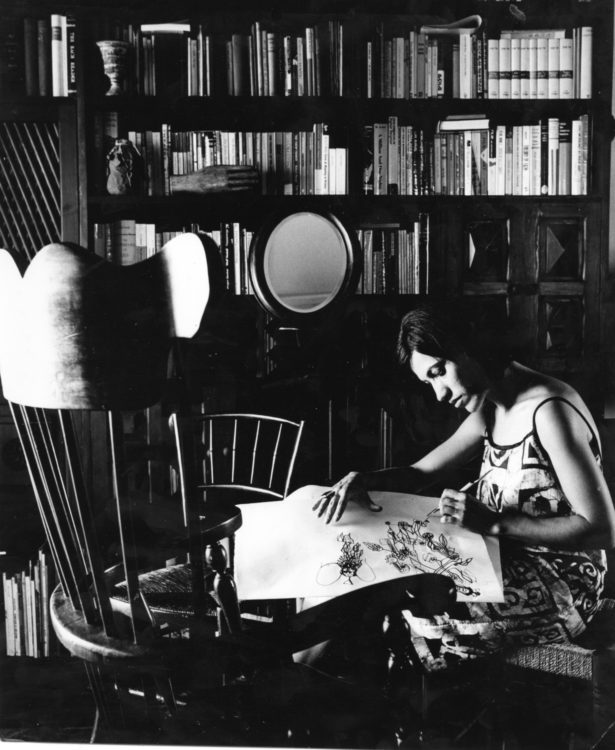

“Isabelle sculpts, auscultates, conceals herself and exults”. Marcel Duchamp needed but these few words to describe the rich and complex personality of this major yet too little known artist of the post-war Parisian scene. Isabelle Waldberg met the sculptor Hans Meyer in Zurich in 1933, a meeting that would prove decisive for her vocation. After training at various academies in Montparnasse and a study trip to Italy in 1936, she acquired a solid intellectual education at the École pratique des hautes études en sciences sociales (ethnology and sociology). From that time onward, she counted among her friends Giacometti, Masson, Leiris, Bataille – she was the only female member of the review Acéphale – and Patrick Waldberg, who became her husband and was one of the most learned analysts of the surrealist movement. She joined him in New York in 1942 and was quickly welcomed by the group Artists in Exile, especially the Surrealists, and in particular the painter Roberto Matta. In 1944, her sculpted work began to exceed the strict framework of Surrealism, moving towards a form of totemist abstraction: she and Matta, Robert Lebel, and Max Ernst discovered with much enthusiasm the ephemeral topographies of the Navajos and Inuit wood and feather masks. Her first sculptures were light, fence-shaped constructions made out of flexible wicker or beechwood canes. These delicate, almost artisanal pieces drew on the dreamlike poetics inspired by seeing Giacometti’s Palace at 4 a.m. in 1936. Next came her metal constructions, also fragile and see-through, made out of tight weaves of loose meshes or interlacings of curved lines, the abstract outline of which can be compared to the work of Mark Tobey, William Stanley Hayter, and some abstract expressionists like Baziotes and Gorky. Acknowledgement of her work came immediately.

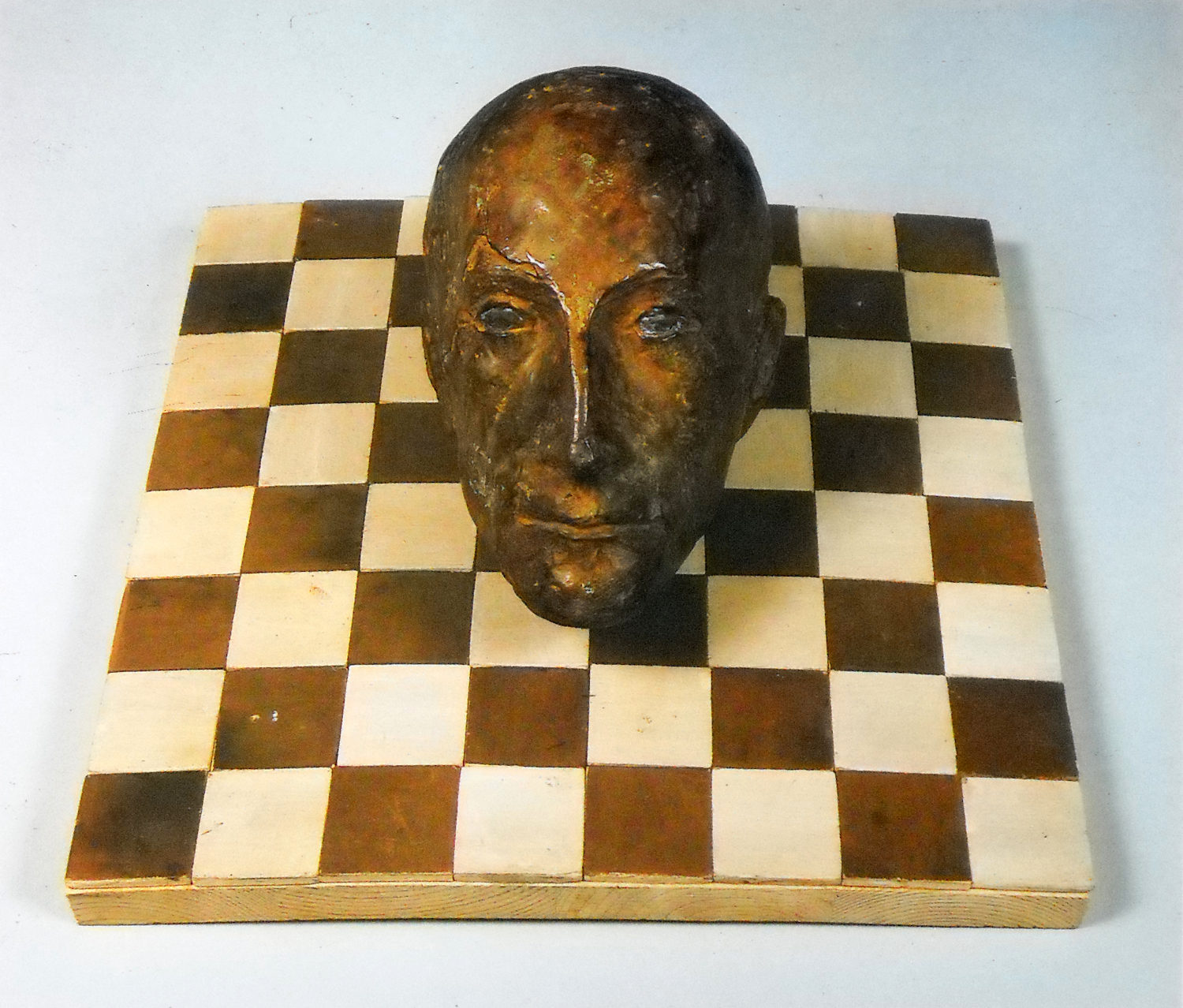

In 1944, her pieces were sent to The Art of This Century Gallery and to the Museum of Modern Art (for her first exhibition of sculptures), then to the Twenty Painters exhibition at the Peggy Guggenheim Gallery, where it was shown alongside works by Rothko, Hare, Pollock, Motherwell, and Vail. Her first solo show was held in 1945 at The Art of This Century Gallery at the same time as her counterpart Alice Rahon. Waldberg’s return to France in 1946 (working at M. Duchamp’s studio) marked a radical change in her work: she gradually reverted to a more massive approach, with slabs of plaster mounted on plinths and ridden with cracks and holes – an exorcising work of “incarnate” morphologies turned into signals or trophies (Your Highness, 1955; Agarien I, 1958), the plastic language of which resembles that of Barbara Hepworth’s hollowed shapes, Alicia Penalba’s orphic totemism, or Germaine Richier’s scratched figures. Despite being awarded the Bourdelle Prize in 1961, working as a sculpture teacher at the National School of Fine Arts, and the appreciative support of Lebel, René de Solier, Giacometti, Arp, and major art collectors, Waldberg chose to work in increasing solitude in order to meet the requirements of the powerful and personal expression of her art: large swathes of free-flowing matter, forming increasingly heavy and opaque constructions, places of isolation and flaws (Chasse; Coffret; Cuirasse) – the dwellings of a magnificently complex artist’s temperament.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017