Laure Albin Guillot

Bouqueret Christian (ed.), Laure Albin Guillot ou la volonté d’art, exh. cat., Musée de l’Ancien Évêché, Évreux; Villa Aurélienne, Fréjus; Musée Sainte-Croix, Poitiers, (29 June–29 September 1996; 26 October 1996–12 January 1997; 6 February–27 April 1997), Paris, Marval, 1996

→Desveaux Delphine (ed.), Laure Albin Guillot : l’enjeu classique, exh. cat., Jeu de Paume, Paris ; Musée de l’Élysée, (26 February–12 May 2013; 3 June–25 August 2013), Paris, La Martinière / Jeu de Paume, 2013

Laure Albin Guillot, ou la volonté d’art, Musée de l’Ancien Évêché, Évreux; Villa Aurélienne, Fréjus; Musée Sainte-Croix, Poitiers, 29 June–29 September 1996; 26 October 1996–12 January 1997; 6 February–27 April 1997

→Laure Albin Guillot : l’enjeu classique, Jeu de Paume, Paris ; Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne, 26 February–12 May 2013; 3 June–25 August 2013

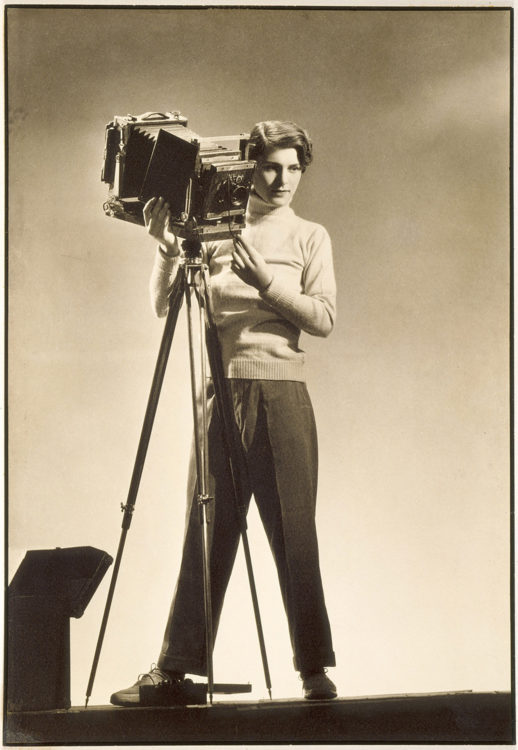

French photographer.

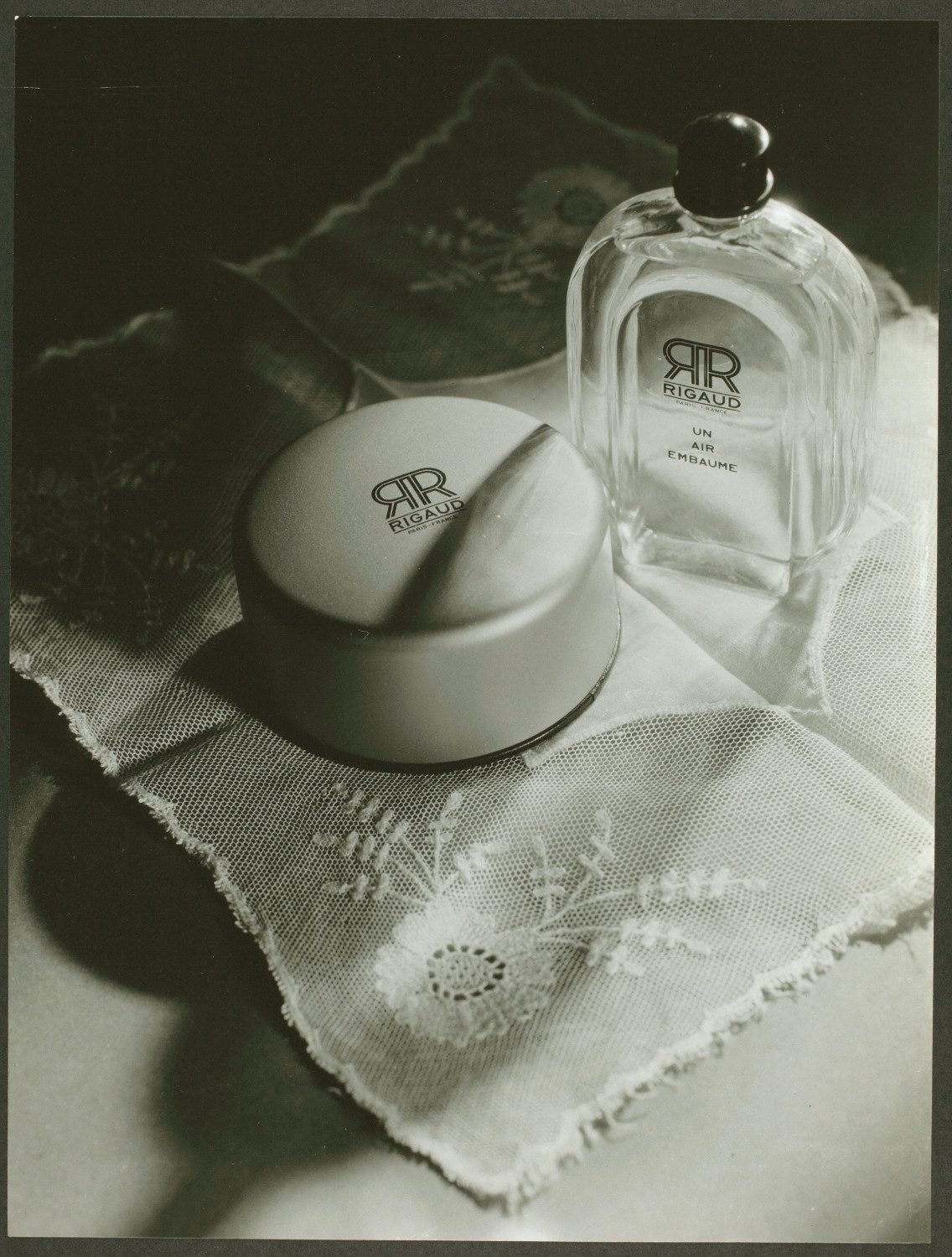

The perfect example of a successful female photographer, Laure Albin Guillot acted as a bridge between two generations of artists: the pictorialists, who wanted to correlate photography with painting, and, as from the 1920s, the Nouvelle Vision movement, a group of modern-minded photographers. Around 1901, under the influence of her husband, a doctor, the musician and dancer began to take pictures of microscopic crystallisations and plant cells, which she called “micrographies” [micrographs]. She also photographed landscapes in a pictorialist style, achieving a faint and hazy blurredness with the Eidoscope and Opale lenses, and paying great attention to her prints by thoroughly researching photographic paper. She also started photographing her family and circle of friends. Quickly recognised as a professional portraitist, she became a defender of the “psychological” portrait: her fellow photographer Emmanuel Sougez, the leader of “pure photography”, praised her sensitivity. After her husband died, she not only made a living from commissioned portraits, but also as a pioneer in the fields of fashion and commercial photography. Like many photographers during the interwar period, she managed to simultaneously pursue a successful commercial career and intense creative activity.

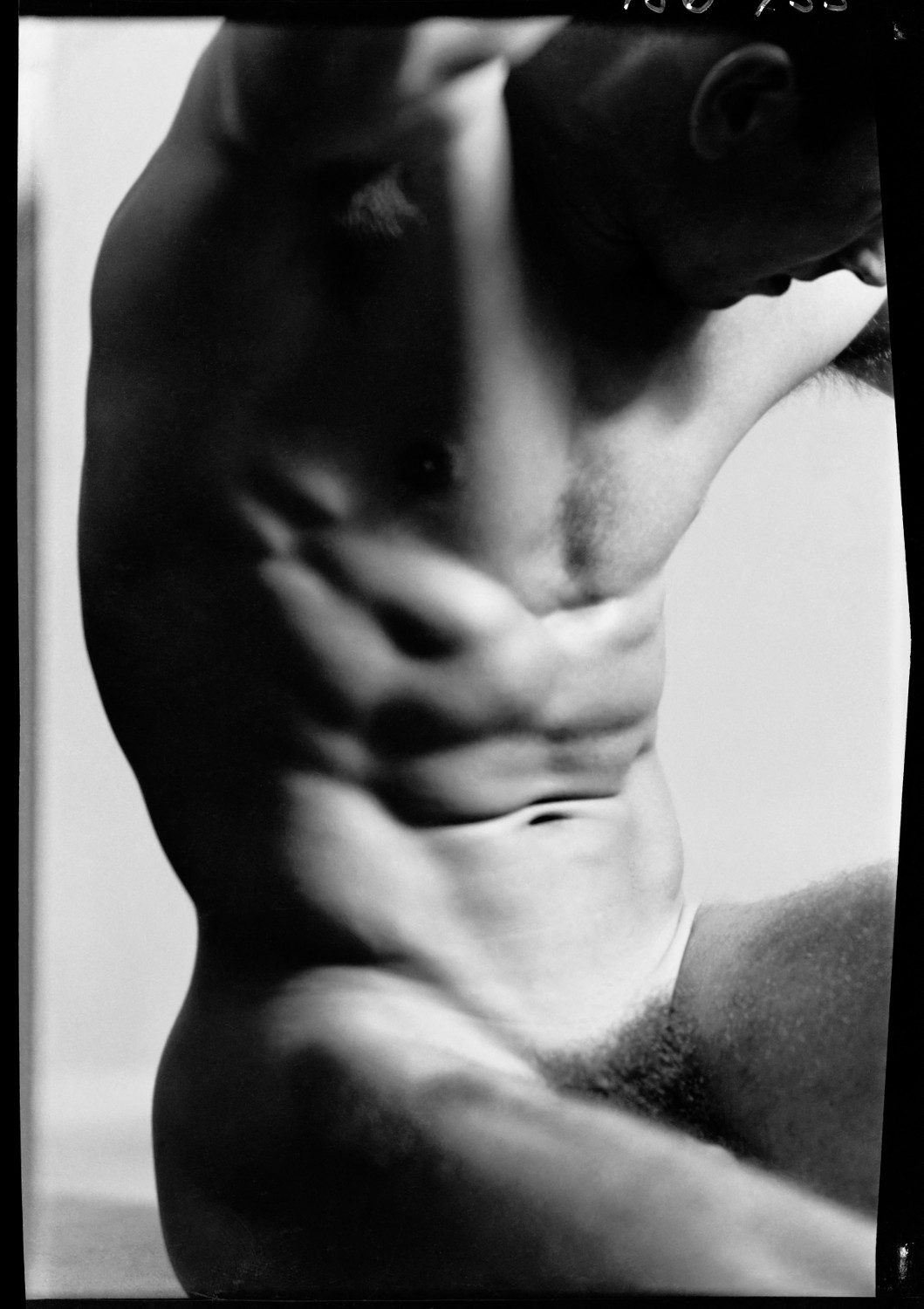

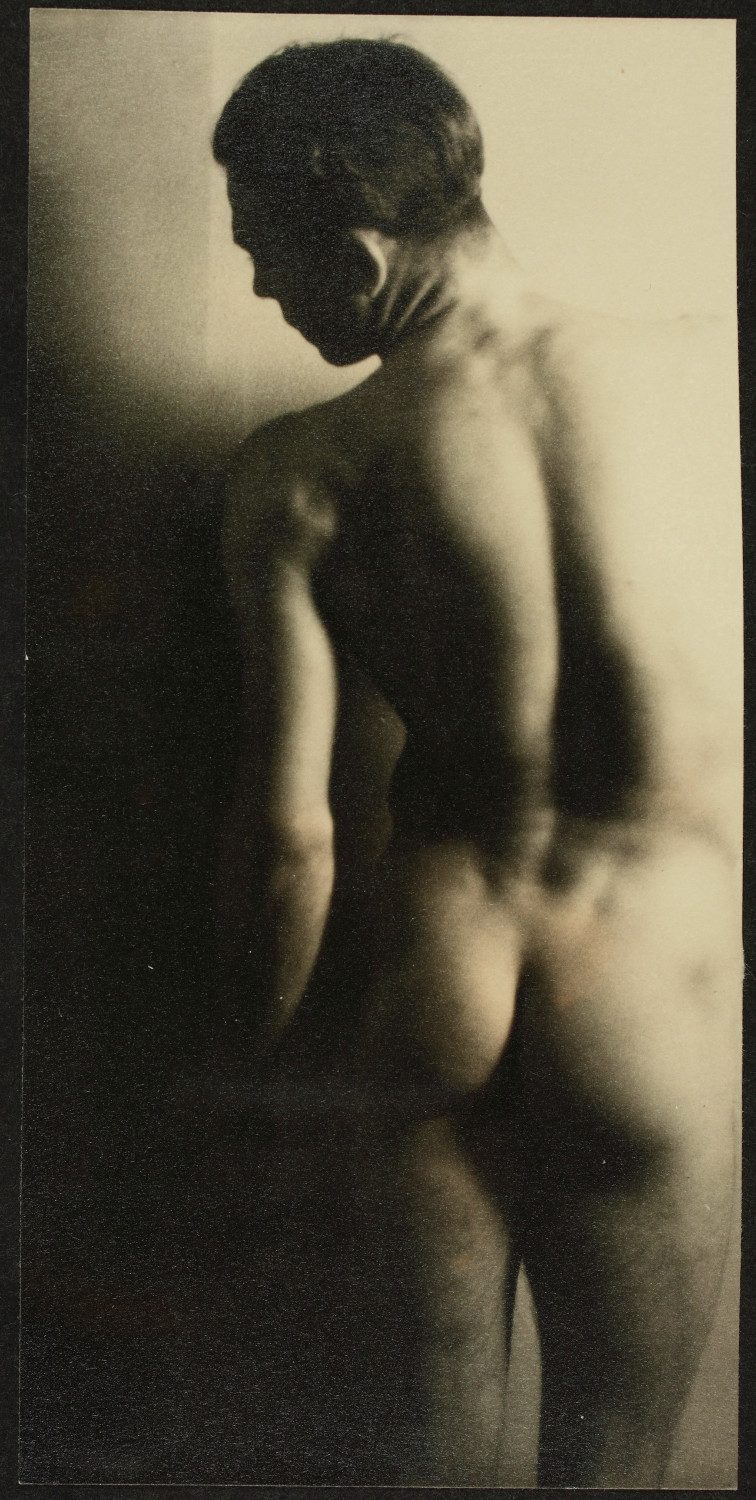

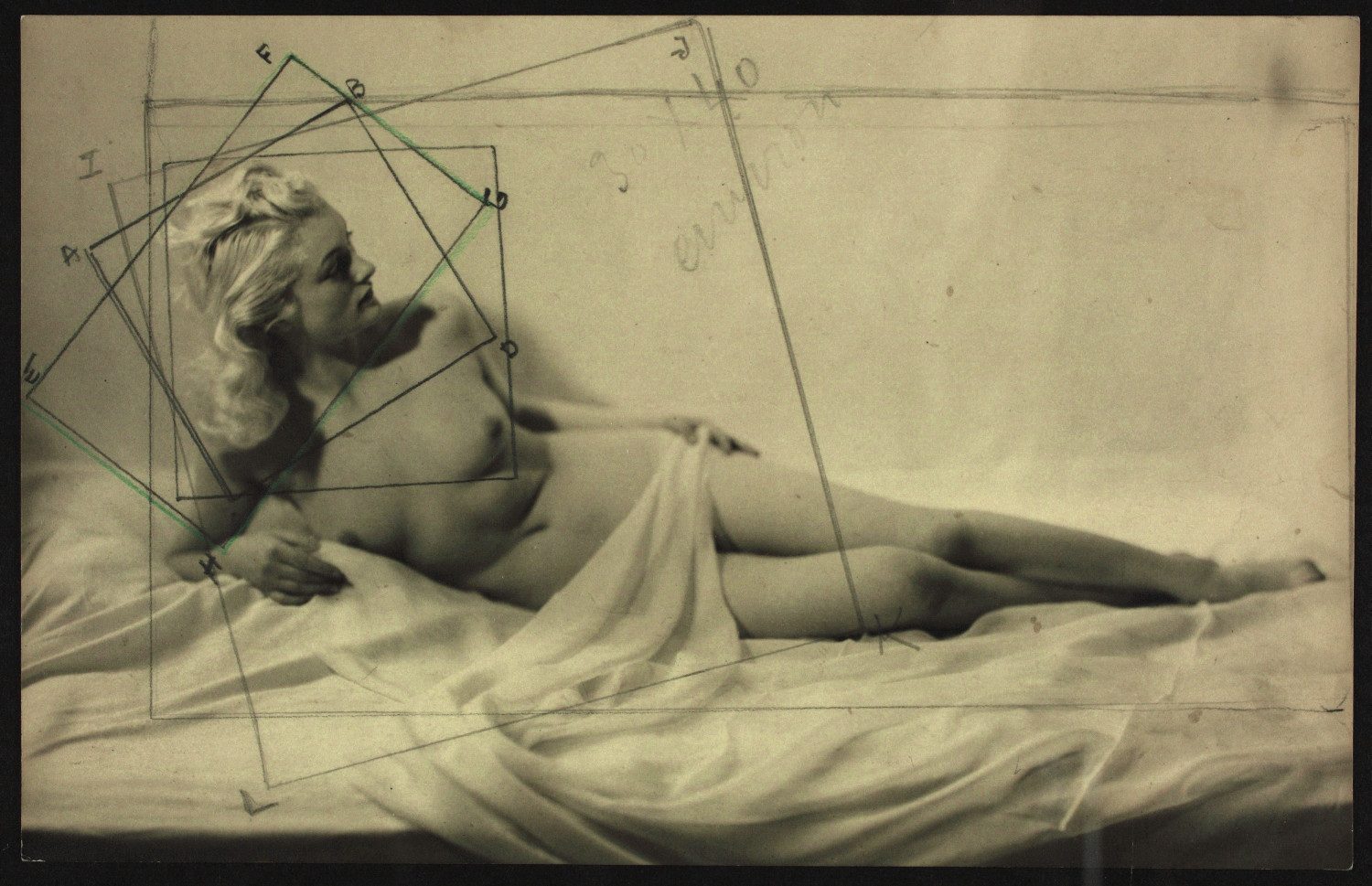

Striving for the recognition of her art in the 1930s, she founded the Société des artistes photographes [Society of artist photographers] in 1932. With Sougez, she obtained the creation of a photography section at the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris, and even contemplated the foundation of a museum of photography in the new Trocadéro pavilion. The artist’s work on nudes shows how cleverly she transitioned from a pictorialist to a modern aesthetics. While she photographed female nudes in classical poses and compositions in the early 1920s, her work saw a formal evolution in its use of whites and framing between 1927 and 1934. She was also one of the only photographers of the 1930s to approach male nudes beyond the domains of sport and allegory. At the exhibition Portraits d’hommes [Male Portraits], (Billiet-Vorms Gallery, Paris, 1935), she presented audacious male nudes alongside classic portraits. Her photographs were published in Arts et métiers graphiques (1927) and Vu (1928), and she took part in the first Salon des indépendants de la photographie [Salon of independent photographers], also known as the “Salon de l’escalier” [Staircase salon] in 1928 with, among others, André Kertész.

The event, which was the first salon to be held independently of the Société française de photographie [SFP, French Photographic Society], marked the acknowledgement of the Nouvelle Vision movement and presented itself as the successor of Eugène Atget and Nadar, brought cosmopolite and women artists to the foreground. In 1931, the photography book Micrographie décorative [Decorative micrography], which combined science and art in a collection of 20 plates chosen from hundreds of micrographs, became a key publication despite its limited print run. In addition to the exceptional quality of its prints and the “great evocative power” of its “abstract, regular and often geometrical compositions”, it also elaborated, according to the photography historian Christian Bouqueret, “a new aesthetic vocabulary”. In the 1930s, Laure Albin Guillot was fully involved in the Nouvelle Vision movement, alongside other photographers such as Germaine Krull and Florence Henri. As Bouqueret demonstrated, “advertising played a decisive part in the breakthrough of Nouvelle Photographie”. Albin Guillot took pictures with very clean-cut close-ups for Renault enterprises and Le Bon Marché department stores. She published Photographie publicitaire (1933), and in doing so was the first to defend this type of modern photography. In 1934, she collaborated with the writer Paul Valéry for the illustrated edition of Narcisse, the 14 male nude prints of which met with great success. She then worked with Pierre Louÿs (Les Chansons de Bilitis, 1937), Montherlant, and illustrated Claude Debussy’s Preludes. A pioneer in her field, she blazed a trail for many burgeoning women photographers of the 1930s, such as Yvonne Chevalier, Ilse Bing, Ylla or Rogi André.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Laure Albin Guillot (1879–1962), l’enjeu classique at Jeu de Paume

Laure Albin Guillot (1879–1962), l’enjeu classique at Jeu de Paume