Lee Miller

Calvocoressi Richard, Lee Miller : portraits d’une vie, Paris, La Martinière, 2002

→

Haworth-Booth Mark, The art of Lee Miller, London, V&A publications, 2007

→Allmer Patricia, Lee Miller: photography, surrealism, and beyond, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2016

Lee Miller…A Retrospective, Gammel Holtegaard Museum, 22 January – 6 March 2005

→The Art of Lee Miller, Jeu de Paume, Paris ; SF MOMA, San Francisco ; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia ; V & A Museum, London, 2007 – 2009

→Lee Miller: A Woman’s War, Imperial War Museum, London, 15 October 2015 – 24 April 2016

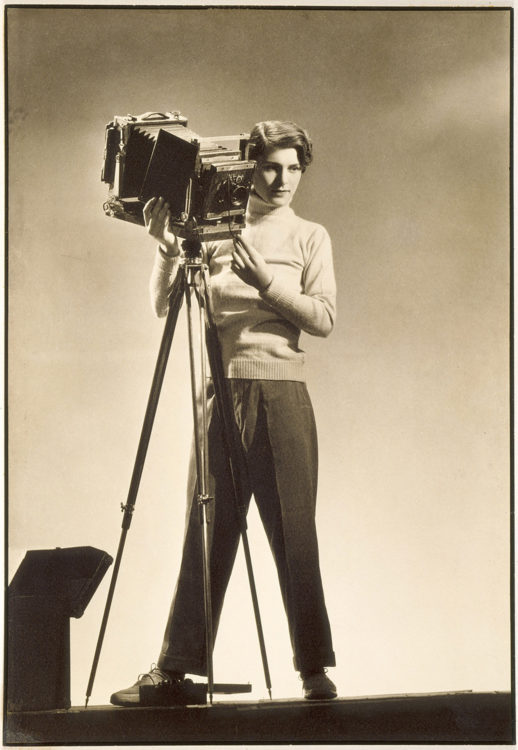

American photographer.

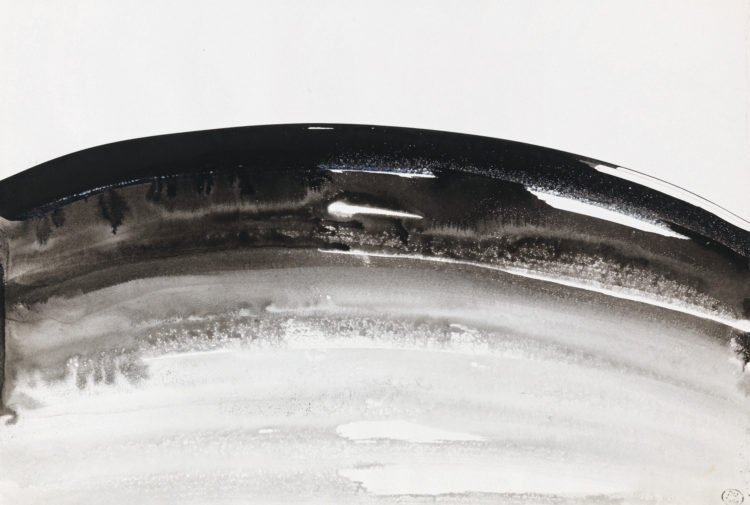

Born into a wealthy family, Elizabeth Miller, known as Lee, learnt photography from her father. After spending a few months in Paris in 1925 to further her artistic and cultural education, she studied painting and draughtsmanship in New York, where she started working as a model for Vogue. Upon returning to Paris in 1929, she became the assistant to the American photographer Man Ray. She posed for his commissioned works and his photographic experiments with solarisations, “rayographs”, tilted frames, and lighting effects. During this time, she also taught herself photographic and lighting techniques. In 1931, she and Man Ray worked together on the advertisement brochure Électricité commissioned by the Compagnie parisienne de distribution d’électricité. The gravure-printed portfolio included ten “rayographs” and is now considered one of the most emblematic surrealist works. In 1932, she was given a leading role in Jean Cocteau’s film The Blood of a Poet. After this, L. Miller began to publish her own works: modernist fashion photographs with strong luminous contrasts and compositions suffused with surrealist aesthetics – combinations of unusual objects, abstract compositions, isolated body parts, mannequins, shop windows, and carrousels. She also continued to work as model for French Vogue, most notably posing for George Hoyningen-Huené.

In 1932, she returned to New York, where she set up her own studio. It quickly became successful, receiving commissions from advertising agencies, fashion houses, perfume and cosmetic brands, and film and theatre production companies. Her black and white photographs bore a resemblance to the modernist images of the Nouvelle Vision movement, and her commercial activity came as no obstacle to her relationship with avant-garde artistic circles. The gallerist Julien Levy presented a selection of her portraits on the occasion of two group exhibitions in 1932, and organised her first solo show of architectural views, still lifes, and portraits in 1933. From 1934 to 1939, she lived in Cairo with her husband, Aziz Eloui Bey, an Egyptian senior official. She then returned to Europe, where she lived with British artist Roland Penrose, a member of the surrealist movement and friend of Paul Éluard and Pablo Picasso.

At the outbreak of World War II, she remained in London, where she published several articles illustrated with photographs in British Vogue, for which she became one of the leading photographers. Her fashion photographs stood alongside documentary views, portraits, and pictures of everyday life during the Blitz. In 1941, she published a series of photographs documenting unusual scenes in the aftermath of the bombings; in a surrealist vein, Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain under Fire (edited by Ernestine Carter) included pictures of mannequins left lying in the street, crushed typewriters, and statues covered in rubble. She was accredited by the US Army as an official war correspondent for Vogue Britain in 1942, which allowed her to photograph the battlefront. Her photographs documented different aspects of the war, from the life of a military hospital in Normandy to street scenes in Germany. In 1945, she photographed the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau. After the War, she continued to shoot fashion photographs and portraits for Vogue for a few years, after which she chose to focus exclusively on co-writing articles and biographies with R. Penrose. Despite her ability, and considerable courage, to shift from fashion photography to the most challenging form of photojournalism, L. Miller only gained recognition late in life. Like Tina Modotti, the wife of Edward Weston, and like Dora Maar, Pablo Picasso’s partner, she belongs to an interwar generation of women who, because they were the wives and muses of famous artists, were pushed out of the limelight and had their personal work ignored until years later.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Lee Miller's exhibtion at Victoria and Albert Museum in London

Lee Miller's exhibtion at Victoria and Albert Museum in London