Leonora Carrington

Garcia Ponce, Juan, Leonora Carrington, Mexico, Era, 1974

→Aberth, Susan L., Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art, Burlington, Lund Humphries, 2004

→Eburne, Jonathan Paul, Leonora Carrington and the International Avant-Garde, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2017

Leonora Carrington: Paintings, Drawings and Sculptures, 1940–1990, Serpentine Gallery, London, 11 December 1991 – 26 January 1992

→Leonora Carrington: What She Might Be, The Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, 23 December – 30 March 2008

→Leonora Carrington, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 18 September 2013 – 26 January 2014

British writer and painter.

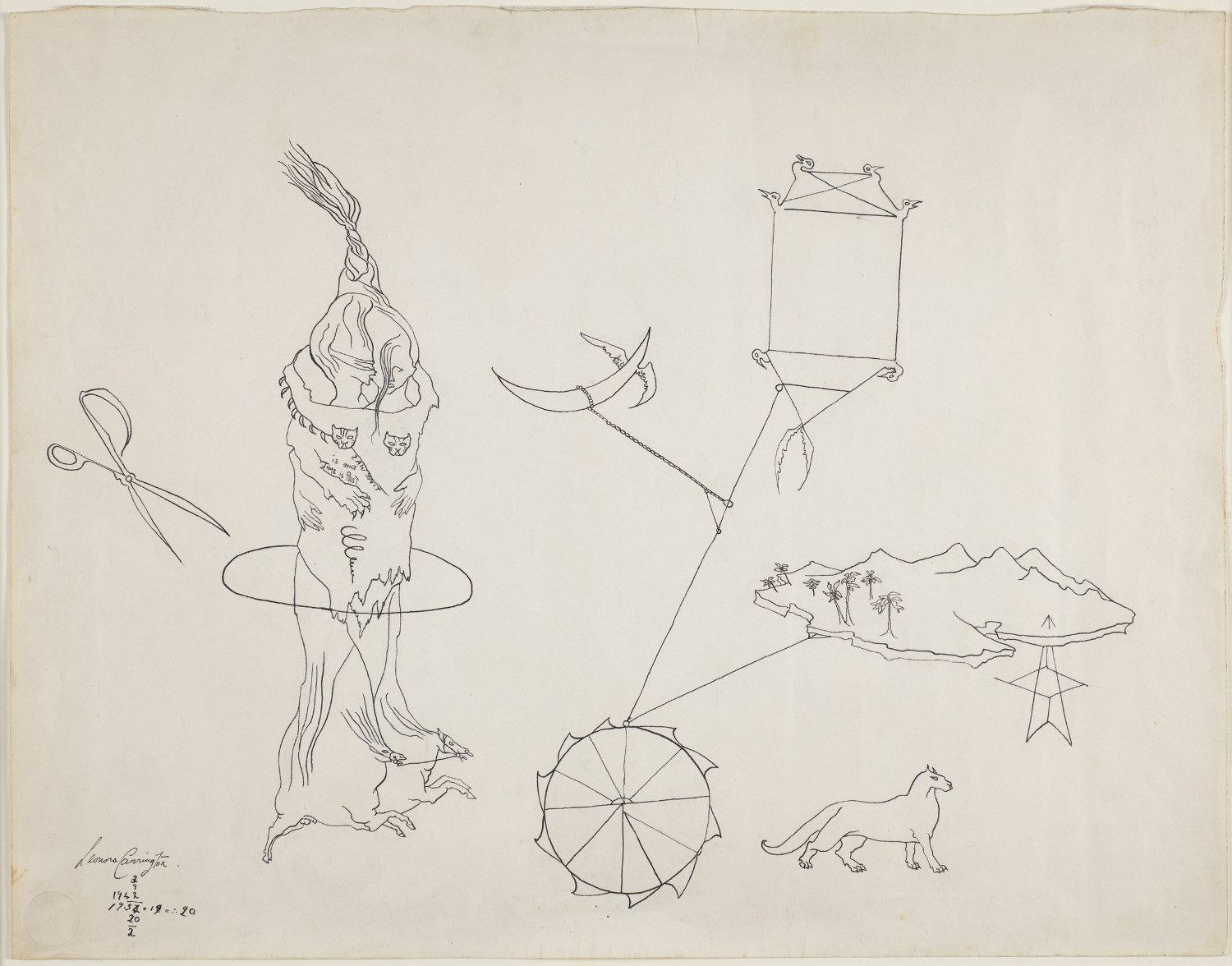

Born to a wealthy British family, Leonora Carrington spent some time in Florence as a teenager and studied painting at the atelier of Amédée Ozenfant. She became fascinated by the work of Max Ernst and later met the no less fascinating painter in person. The pair spent three passionate and creative years in France before being separated by the Second World War, following which L. Carrington entered a deep depression, which she documented in French some years later in En bas (Down Below, 1973). She managed to escape Europe and, after spending a little over a year in New York, finally settled in Mexico. There, she developed strong friendships with the painter Remedios Varo and the photographer Kati Horna, and with members of the Mexican intelligentsia, particularly Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes. But she truly found her roots by getting to know Native populations and, like Benjamin Péret, became interested in their stories and symbolic values. It was also in Mexico, at the age of 28, that she met her lifetime partner Emeric “Chiki” Weisz, gave birth to their children, and tirelessly and unrelentingly painted and exhibited a considerable body of work. The stories and longer fantasy tales she wrote, first in French then in Spanish, drew their inventiveness from the intervals between the two languages. From her Maison de la peur (The House of Fear, 1938), illustrated by Max Ernst, to her later stories from the 1950s and ’60s, her works were first published in French or translated into French by Henri Parisot, before being reworked and published in their English versions. These writings, manipulated and reworked both by others – translators – and herself, have a very special status.

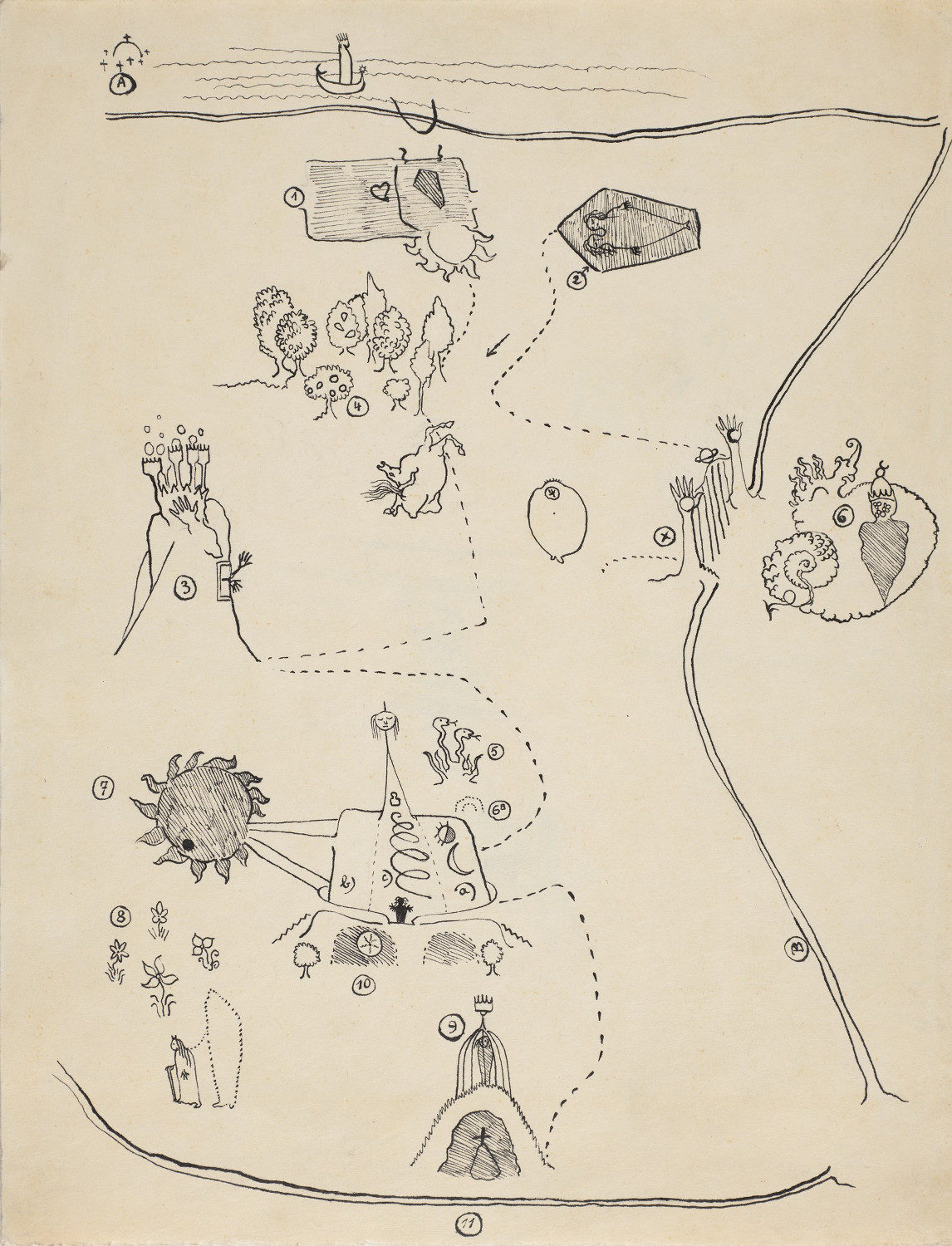

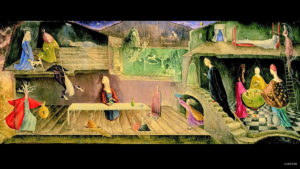

Her painted and sculpted works, represented by two pieces at the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition, were completely in line with the tradition of oneiric realism. Their pictorial quality is refined, their imagery complex, and words are prominently featured in the symbolism that pervades many of her pictures. Her explorations, as much in her stories as in her visual work, are based on the unease caused by the threat to individual liberty. How does one ward off the discord within one’s bodily ego, since the relationship between its parts and sum is problematic, and since the process of embodiment is not clearly embraced? Food – the way it is ingested, the way it is cooked – became a central topic for L. Carrington. In her painting Hunting Breakfast (1956), a cabbage becomes a caballo [horse], an image endowed with an identity; in Orplied (1955), the artist depicts a joyous cohort led by a white winged horse, like the image of an idealised ego. This era of myths came with its corresponding large cosmological canvases: in Le Retour de la Grande Ourse [Return of the Ursa Major, 1966] or Round Dance (1968), movement symbolises the return of a warrior female order, as in Celtic myths, or of a perfection of movement. Her mural El mundo mágico de los Mayas [The Magical World of the Mayas, 1963-1964] captures mythology’s powerful ability to organise time and space. L. Carrington believed in the transcendence of dreams. Her aim was to internalise, or better yet, to ingest, the wisdom that they embody.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Leonora Carrington – Britain's Lost Surrealist

Leonora Carrington – Britain's Lost Surrealist  Leonora Carrington's Portrait of Max Ernst

Leonora Carrington's Portrait of Max Ernst