Lygia Pape

Herkenhoff Paulo, Mulheres do presente, a clareza entre sombras, São Paulo, Instituto Tomie Ohtake, 2016

→Lygia Pape, a multitude of forms, exh. cat., Met, New York (2017), New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017

Lygia Pape: Gavea de Tocaia, Fundação de Serralves, Porto, 14 October – 24 December 2000

→Lygia Pape, Magnetized Space, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 24 May – 3 October 2011 ; Serpentine Gallery, London, 7 December 2011 – 19 February 2012 ; Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 17 March – 13 May 2012

→Lygia Pape: Ttéia 1,C, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2 February – 13 May 2018

Brazilian sculptor, engraver and filmmaker.

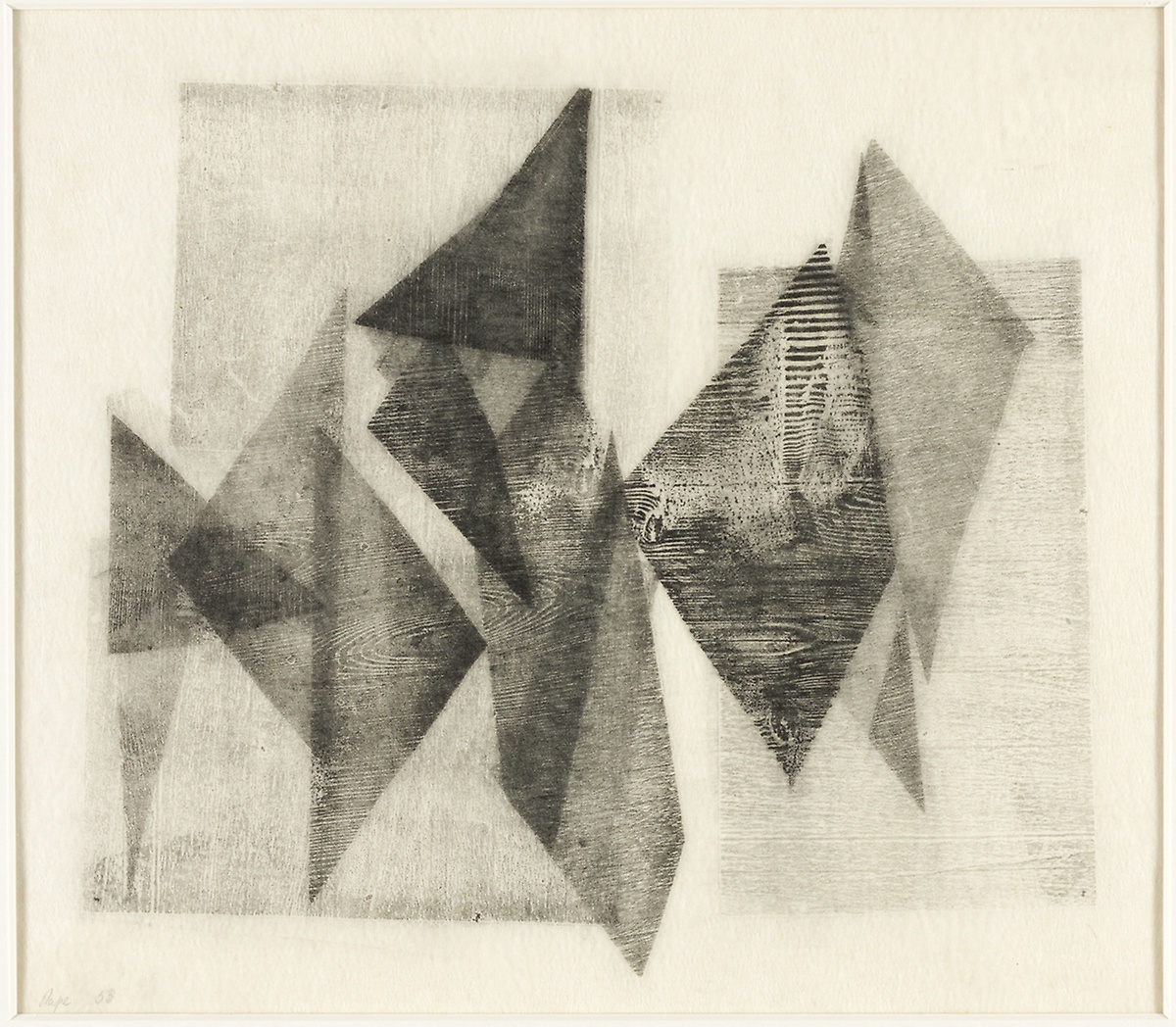

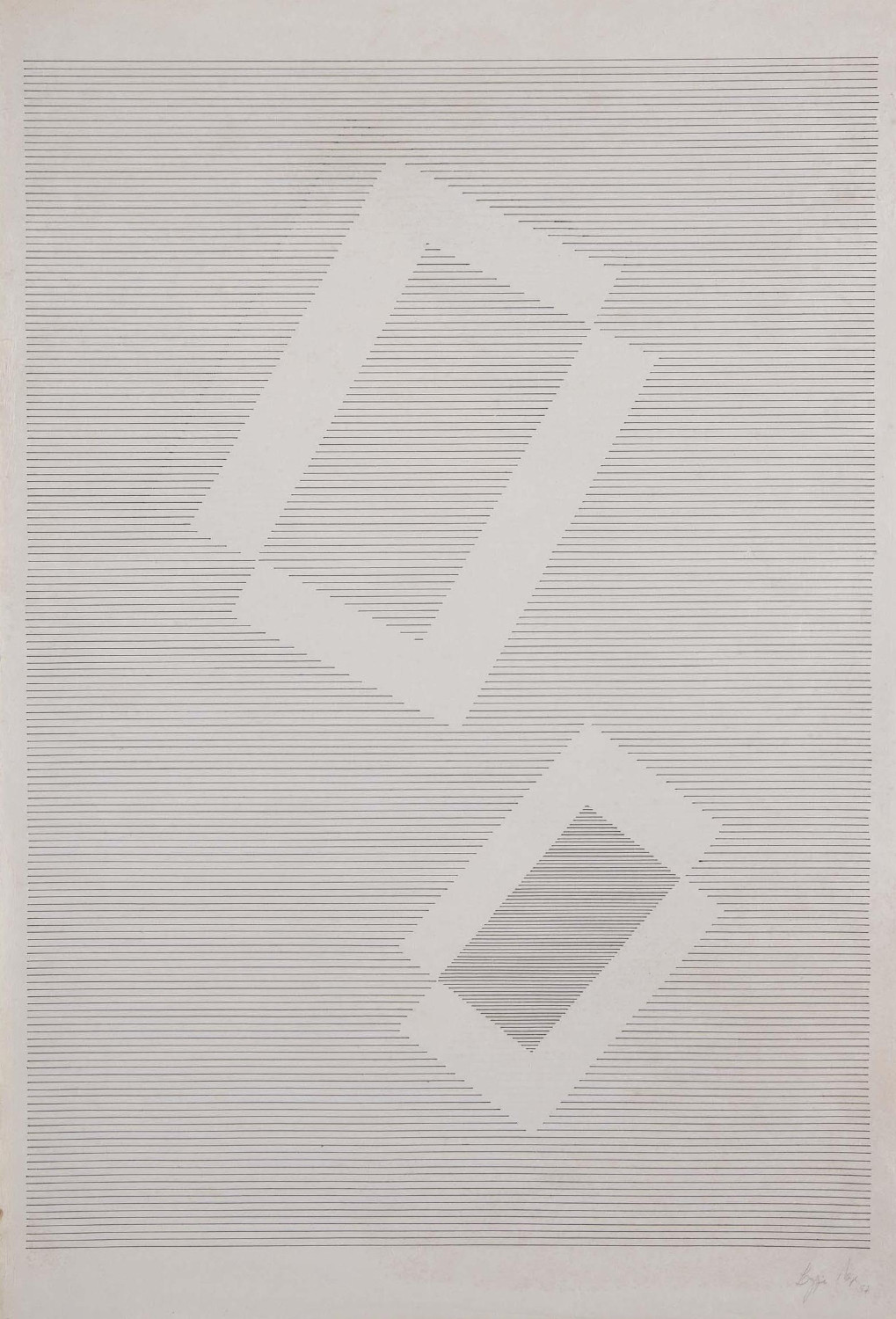

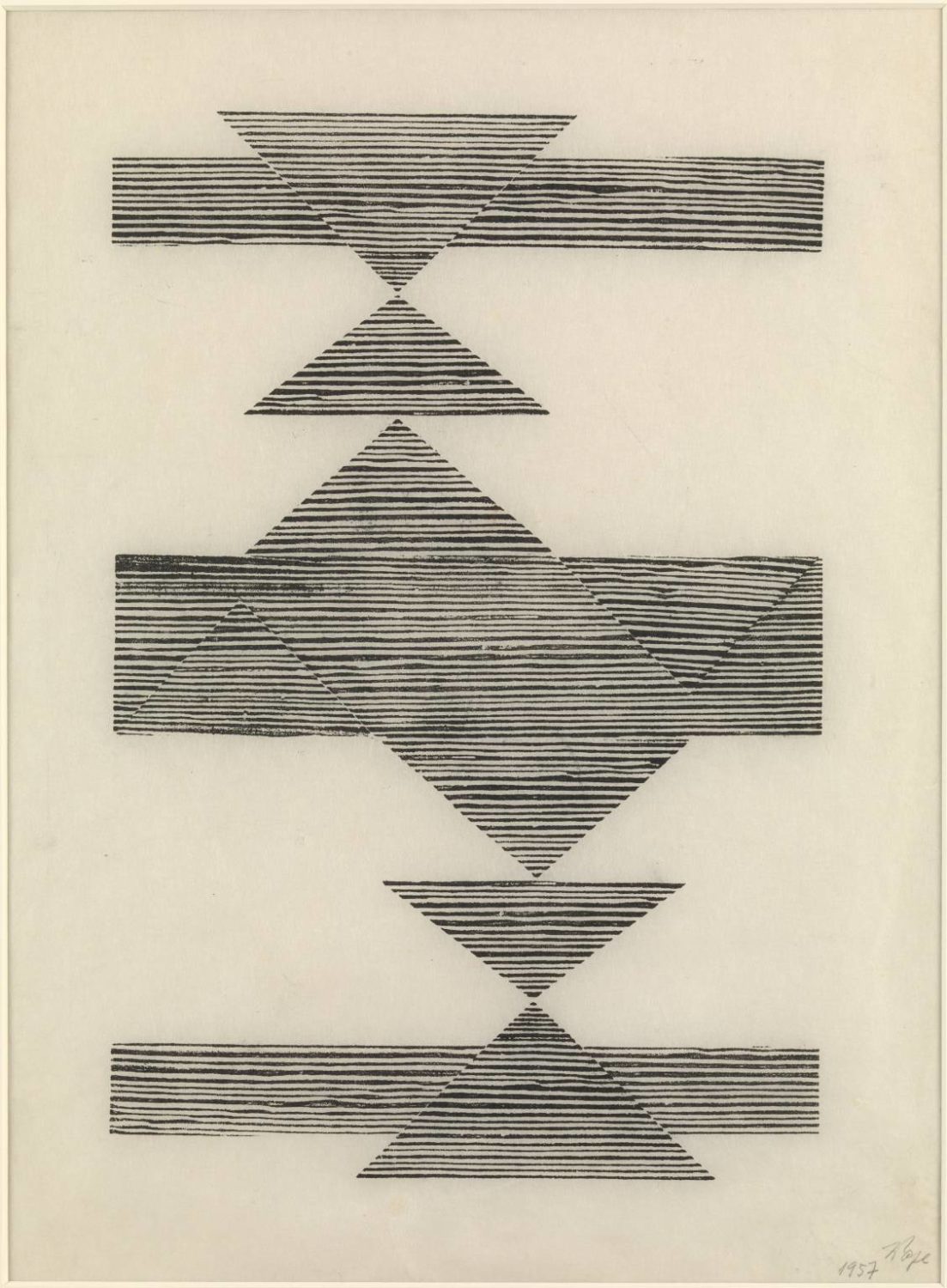

In a context of cultural enthusiasm that favoured industrial progress, in the early 1950s the Brazilian art scene was dominated by concrete art, an abstractionist movement similar to Bauhaus, De Stijl, Suprematism and Soviet Constructivism. The concrete art group Frente in Rio de Janeiro was Lygia Pape’s fist artistic filiation. At the time, she was a young disciple of Fayga Ostrower at the school of the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro. Her series Tecelares (weavings), produced between 1955 and 1959, was true to the concrete programme in the spirit of bringing artistic practice closer to industrial work, and in the conception of the art object as an arrangement of visual elements – planes, colours, geometric forms – which was self-expressive and independent of any symbolic or representative ambition. However, towards the end of the 1950s Rio’s concrete art moved away from the “Paulist” side (the more cerebral art of São Paulo) of the movement opposing the dogmatic geometric formalism of the latter – a desire to open the work to a maximum of vital dimensions.

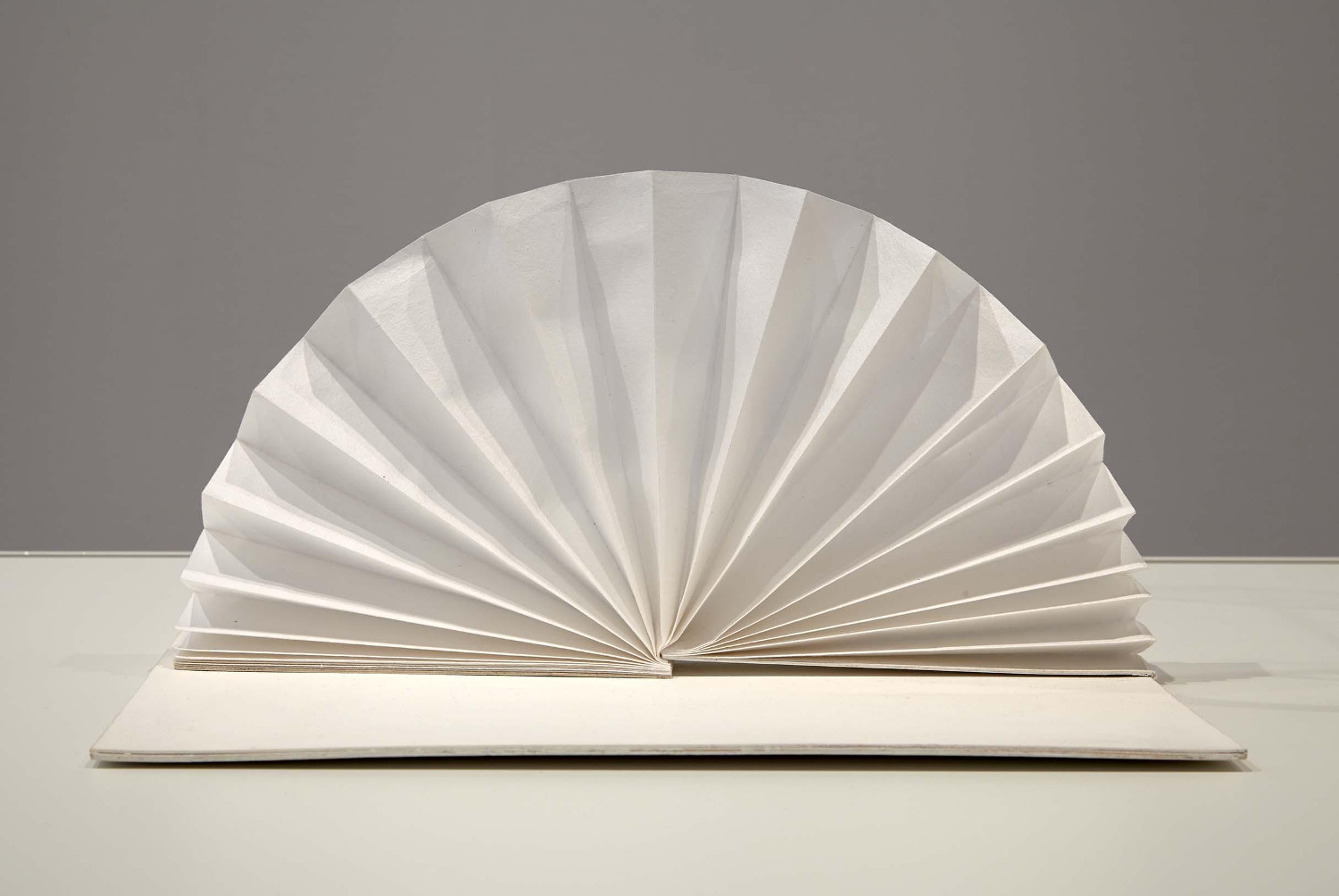

L. Pape was the instigator of this dissent, accomplished by the publication of the Manifesto Neoconcreto in 1959 which she co-signed with Hélio Oitica (1937-1980) and Lygia Clark (1920-1988). Like them, she rejected the concrete rationalism that had nurtured them, and advocated for the freedom of experimentation and subjectivity, as well as a humanistic and participatory vision of art. Ballet neoconcret I, created in collaboration with the poet Reynaldo Jardim (1926-2011) and presented at the Copacabana Theatre in 1958, was a pivotal scenographic experience of the neo-concrete rupture. The dancers’’ bodies served as living substrata for the coloured geometrical forms, the only visible presence on the dark stage. Starting in the 1960s as a director, screenplay writer and editor, L. Pape contributed to several films of Cinema Novo, a new form of documentary film whose language defied the supposed neutrality of distance agreed upon in the genre giving way to a great deal of visual invention. Moving between sculpture, installation, performance and video gave rhythm to her work. Her recognition in the artistic world of Brazil was nevertheless first linked to a succession of participatory projects from the 1960s that violently criticised political and artistic institutions. O Divisor (1968) was a performance in the form of a disturbing metaphor for the mechanised society that sacrificed the integrity of individuals. Roda dos Prazeres (1968) was a sensory experience aimed at denouncing the fetishism that often targeted the art object. Eat me: a gula ou a luxúria, her first solo exhibition, at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro did not take place until 1976. The works, made from objects evoking the codes of feminine seduction (hair, aphrodisiac lotions, lipstick, apples, fake breasts) were sold at the end of the exhibition. Through this allusion to the fight against the commercial use of the feminine image specific to the feminist cause, the artist demonstrated her resistance to the stranglehold of the artistic system. Her theoretical reflection played an important role in her career. She taught the semiotics of space at the Universidade Santa Úrsula (1972-1985) and obtained a master’s degree in the philosophy of art in 1980 from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. In the 1990s she began receiving a great deal of international attention. Until her death in 2004 she continued her work, which constantly conveyed political denunciations – such as Carandiru (2001), a sculpture commemorating the massacre of 111 prisoners in the eponymous prison –and metaphysical reflections supported by explicit metaphors – Rideau de pommes (1996) for example, an installation referring to the notions of the life cycle and degeneration. However, L. Pape did not abandon less textual explorations of more purely visual issues, as shown in the installation TTÉITA I, C (2002), presented at the Venice Biennale. An imposing dark space, which seemed to be woven by golden threads, recalled the woodcuts of her Tecelares series from the 1950s and suggested a key to re-reading her entire body of work. Her openness to the complexities of socio-political realities and their polymorphic treatment allowed her to revisit her primordial visual questions with elegant lightness.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2020

Lygia Pape at Hauser and Wirth

Lygia Pape at Hauser and Wirth